It’s hard to think about anything right now except staying safe and keeping loved ones close. But if you’re looking to distract yourself by reading, I suggest Love at the Border: An Adoption Memoir from Mexico, by adoptive mother...

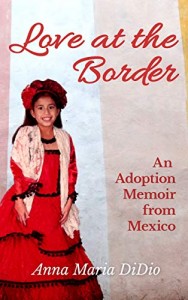

It’s hard to think about anything right now except staying safe and keeping loved ones close. But if you’re looking to distract yourself by reading, I suggest Love at the Border: An Adoption Memoir from Mexico, by adoptive mother Anna Maria DiDio.

When DiDio asked me to read her memoir a few weeks ago, I was happy to oblige. Adoption is my obsession, and I always learn from other people’s stories.

A quick summary: DiDio and her husband were parents to an eight-year-old biological daughter when they adopted seven-year-old Priscilla from an orphanage in Mexico. (To my knowledge, few children are adopted from Mexico today; this story began in the early 2000s.) Priscilla had spent her entire life in the orphanage before the DiDio family brought her to Pennsylvania. Challenges ensued. As DiDio observes about herself as an adoptive parent: “[H]ow much did I really know about Mexico and her experience?” (72). The answer, of course, for DiDio and every adoptive parent in the beginning, is “very little.” We learn as we go, with no preparation.

DiDio’s voice as a writer is candid. I finished her memoir with deep empathy toward Priscilla. DiDio makes clear that Priscilla never asked to be relinquished by her biological mother or separated from her orphanage caregivers–her only family for seven years. Priscilla never asked to be adopted. Throughout the book, Priscilla struggles while adjusting to the new life she never chose for herself. DiDio notes on page 217: “I think [Priscilla] wanted to love us, but still felt disloyal to Mexico.”

The narrative fascinated me, and two things stood out:

First, the added complexity of blending a family with biological and adopted children. This may not add complexity for every family, but it added complexity for the DiDios.

Second, the emotional impact of learning a new language. Priscilla resisted learning English and often asked her parents why they adopted her if they didn’t speak Spanish. The reason this stood out for me is because my kids have visceral, mostly negative responses to learning and speaking Spanish. The language seems weighted with meaning. In some ways, Spanish seems to symbolize something they have lost, or else symbolizes a skill they are expected (by the world) to have mastered. In any case, for children adopted across borders, language represents more than simply saying words.

Love at the Border is a thought-provoking addition to the canon of adoption memoirs. Nancy Verrier, author of The Primal Wound, writes in the book’s introduction,

“This is an honest account…of how important it is for the parents to try to understand the experience from the baby/child’s point of view…. These children, whether from a different country or not, are apt to be very different from the parents and it is important for the parents to notice, make room, and celebrate those differences” (v).

Verrier’s observations are true, and worth remembering.