Product managers can make better decisions if they’ve built transparency and trust with their team. How these decisions are made is also important, and it requires a clear and collaborative process. Here’s a straightforward framework for collaborative decision making...

Originally published on www.mindtheproduct.com, 24 October 2019.

Product managers can make better decisions if they’ve built transparency and trust with their team. How these decisions are made is also important, and it requires a clear and collaborative process. Here’s a straightforward framework for collaborative decision making that is founded in transparency and trust.

Product Decisions

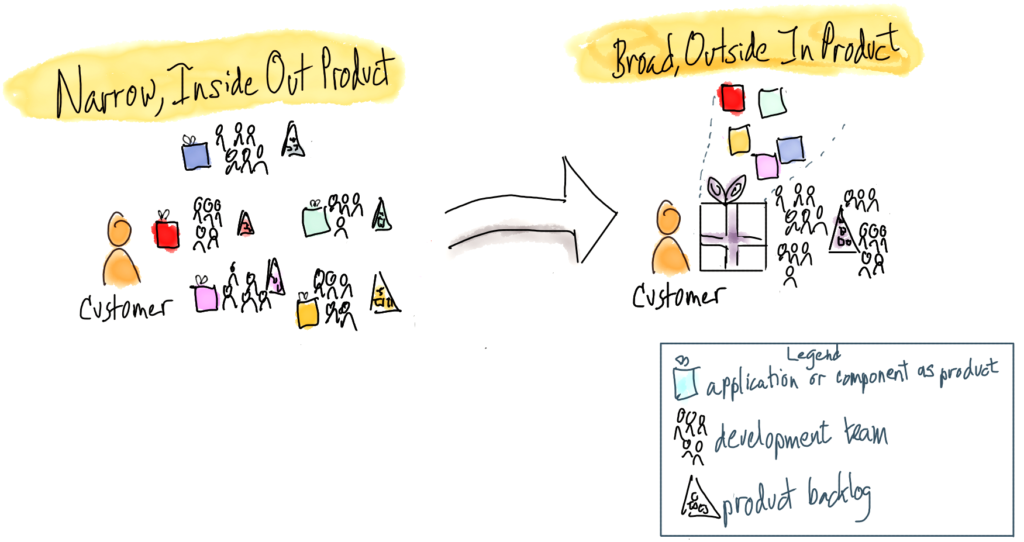

Product decisions are either tactical or strategic. Tactical decisions usually result in short-term actions – like deciding which backlog items to focus on the next delivery cycle and which experiments to run in the next sprint. Strategic decisions provide direction and focus for your product, guide product development action, and ensure alignment within your product ecosystem. Strategic decisions include delineating the product vision, value proposition, product differentiators, and product roadmap.

Both require a product manager to be the decision leader.

Product Decision-Making Traps and Pitfalls

As decision leader you can face challenges that prevent you from making the optimal decision. I’ve frequently seen the following decision-making traps and pitfalls:

Having insufficient or missing information. Being blinded by your biases. This includes confirmation bias (ignoring evidence that doesn’t support your preference) and overconfidence bias (thinking you know more than you do know). Having your decision overridden by others – the HiPPO (highest paid person’s opinion) effect. Stakeholders who challenge or even sabotage the decision.Collaborative Decision Making

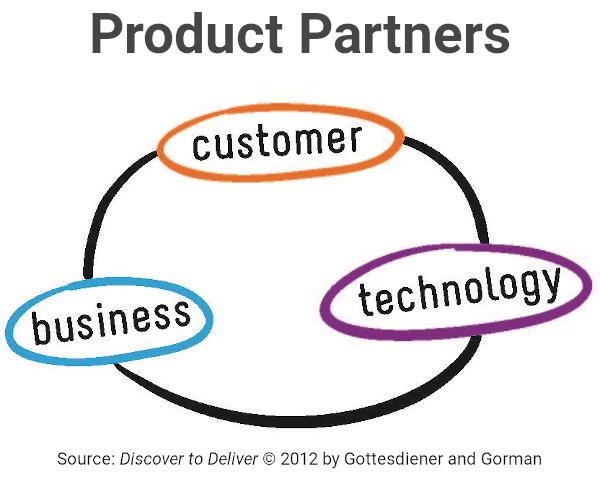

Decision-making difficulties like those above need more than just a decision leader. When product stakeholders aren’t consulted – or their input is obtained without asking about the reasoning behind their thinking – then you risk making unsustainable and poor decisions. You may also reduce trust in your team.

What’s needed is a collaborative decision-making process with the following characteristics:

Diverse stakeholders in the product ecosystem who participate in the decision-making process. These stakeholders provide specific product expertise and a broad perspective that benefits the team. The decision leader obtains the relevant information used to make sound product decisions.This results in a decision-making process that enhances the team’s ability to work effectively together. There are three benefits when people participate in decisions in which they have a stake:

Commitment to the product is higher. The quality of decisions and their outcomes are more successful. A culture of trust develops.Recently I ran a product planning workshop where we needed to decide which experiments to focus on to affect our conversion metrics. The customer service team leader shed light on the support required for user trial sign-up. Without their involvement in the workshop, the sign-up support needs wouldn’t have come up and we would have missed information important to our decision.

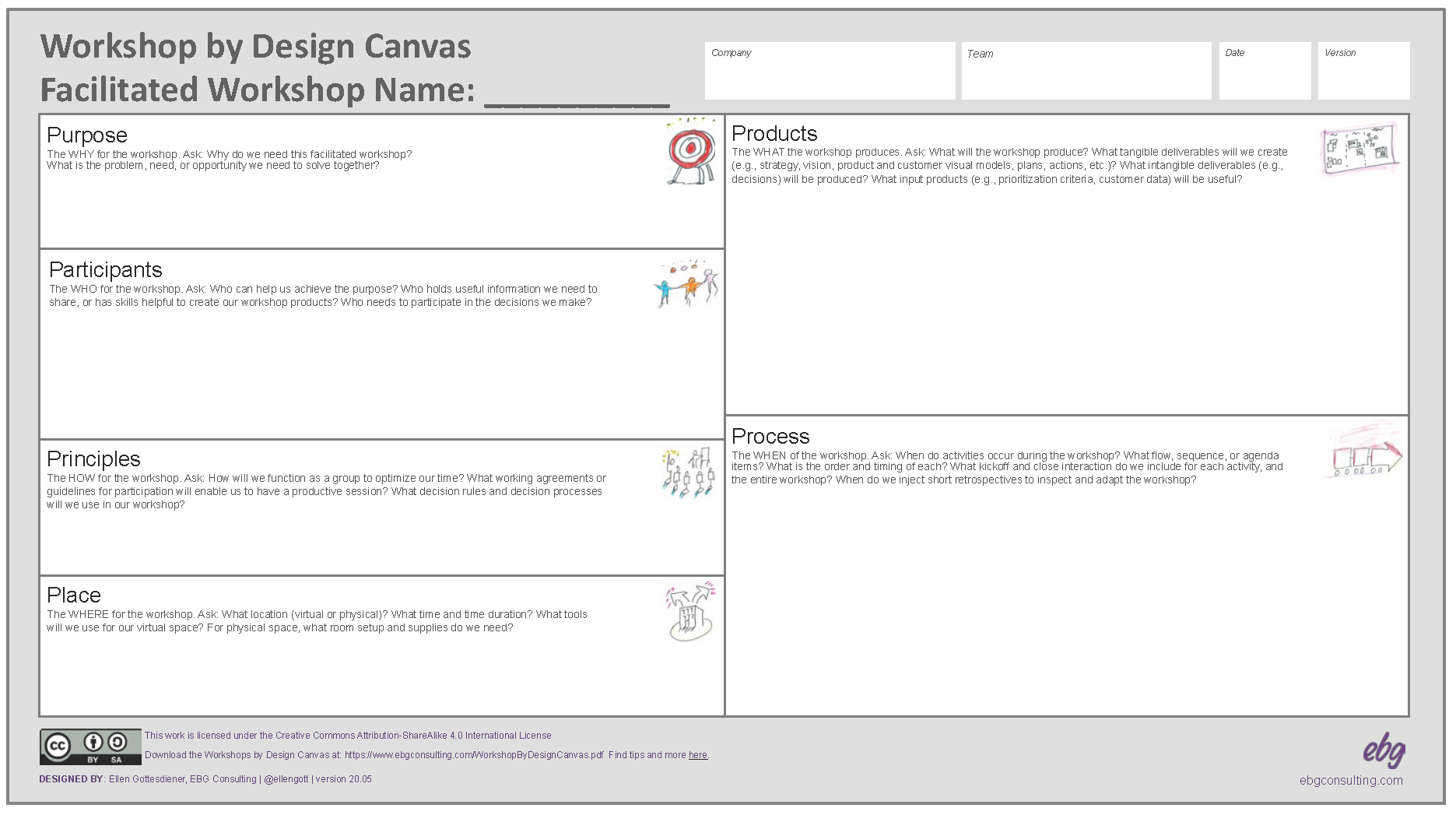

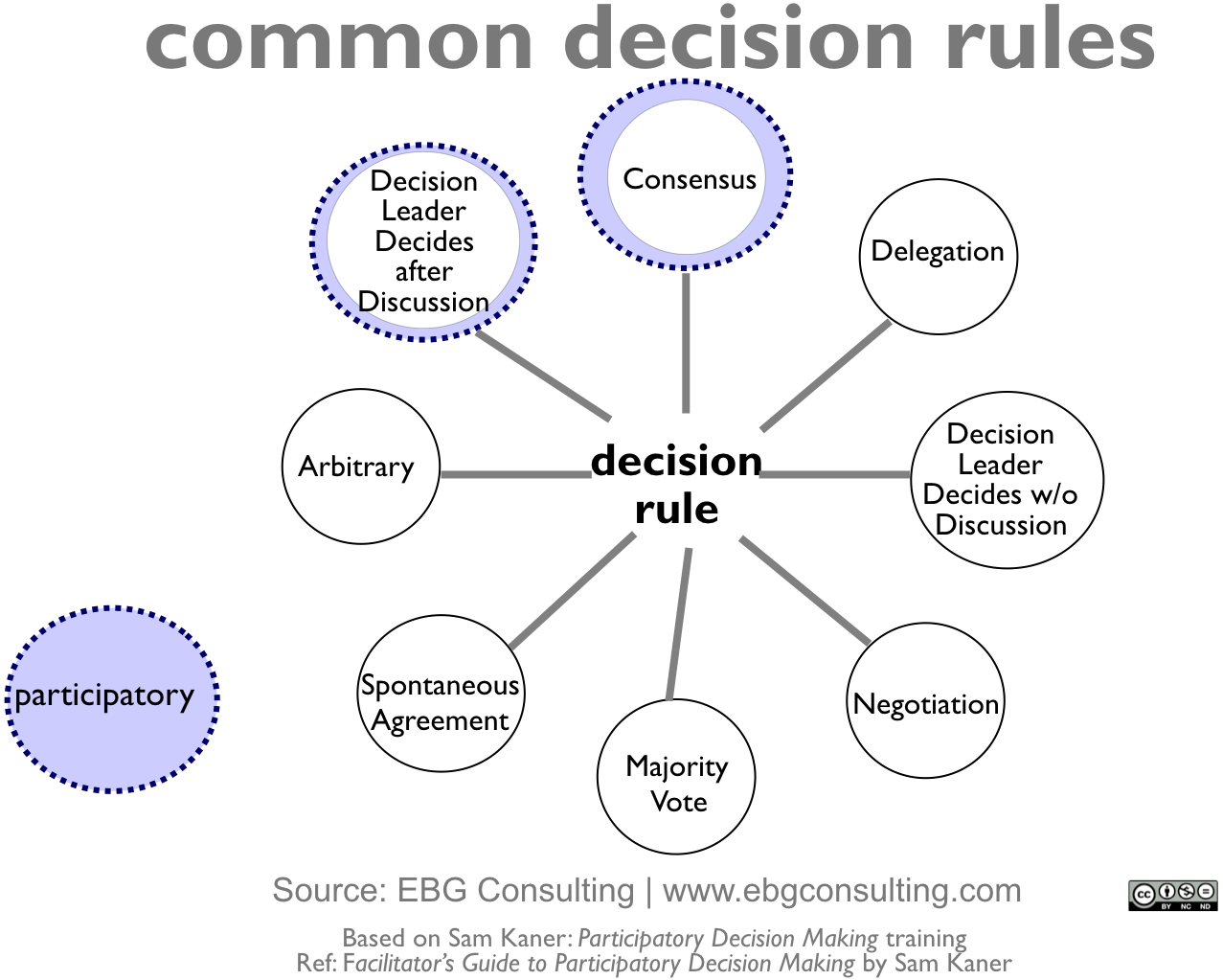

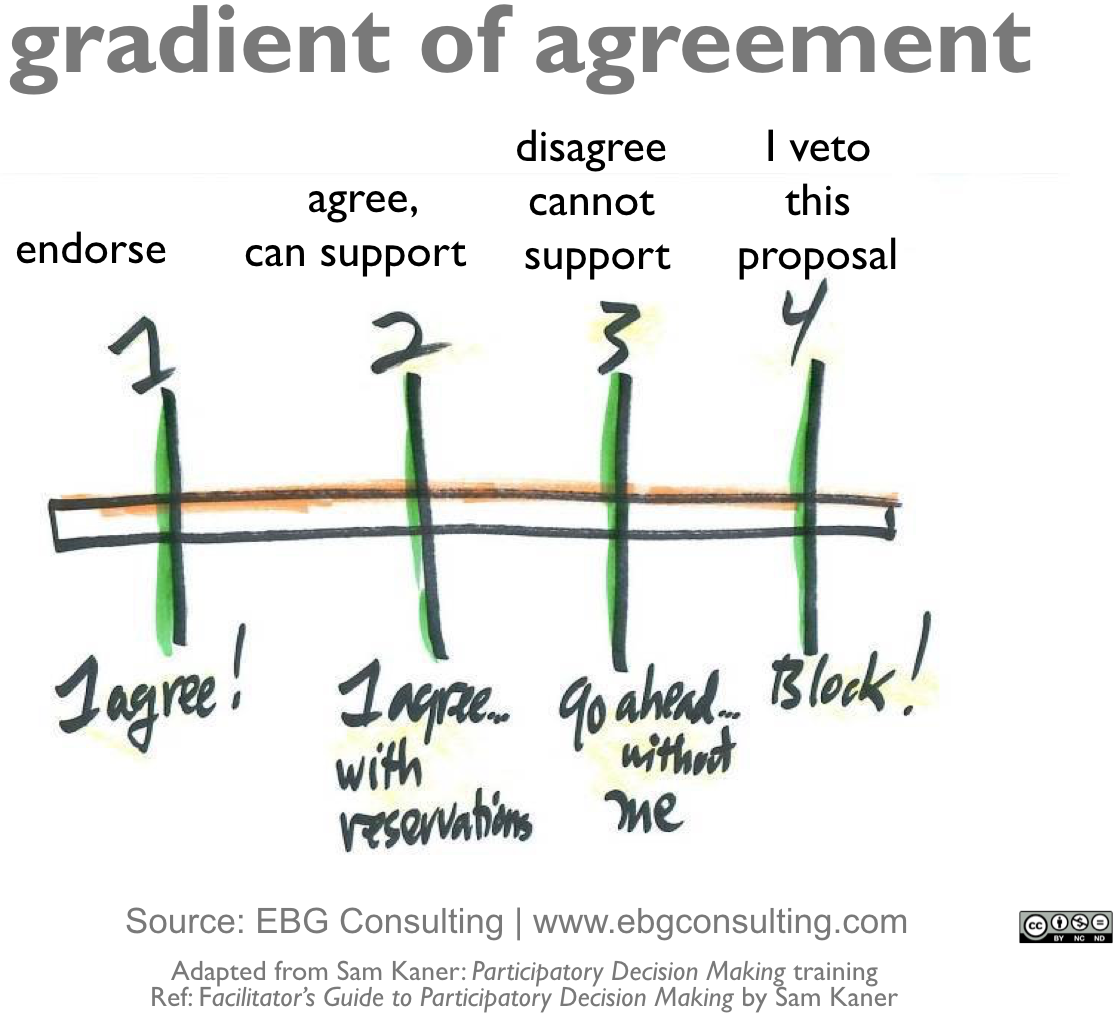

I use two tools to improve team collaboration and reach closure on product decisions: decision rules and the gradient of agreement. Together they comprise a simple framework I call “Decide How to Decide” that relies upon transparency and trust.

Decision Rules

A decision rule is a mechanism to reach closure. It tells participants in the decision-making process when a decision has been made, something many product teams are not explicit about. When a decision rule is not explicitly defined, there is often too much discussion and debate. People are left unsure when and if a decision has been reached and what the decision is. They delay taking action and often act without commitment. The team loses energy and valuable time.

The figure below shows common decision rules. Each decision rule has a different effect on group behavior and is useful in different circumstances. An effective decision rule balances the need to reach closure in a timely manner with the decision’s impact on the business and team. The goal is to be transparent about which decision rule you use.

There are two participatory decision rules that work best for medium- to high-stakes product decisions, such as decision to identify which market segment to focus on for the next product release, or which actions are needed to validate your product strategy. These two participatory decision rules – consensus and decision leader decides after discussion – are best used in a collaborative workshop and give participants the context and relevant information to efficiently discuss options.

Consensus means reaching mutual agreement among all stakeholders, whereby all legitimate concerns have been addressed to reach closure. Consensus can work but is often not practical. I recommend using the decision leader decides after discussion rule for most product decisions.

Gradient of Agreement

The gradient of agreement is a mechanism for testing people’s level of agreement with a proposed decision. It’s shown in the figure below. After discussing relevant information about the decision and generating options about the decisions at hand, the decision leader polls all participants using a four-point scale to find out to what degree each person agrees with the proposed decision. The decision leader then uses this information to inform their decision. If the decision rule used consensus, everyone who participates needs to be in the “zone of agreement” (1s and 2s).

I recently ran a planning workshop where the product team needed to decide which feature to include in the next development sprint. The decision rule selected was decision leader decides after discussion. Amy, the product manager, was the designated decision leader. We reviewed and analyzed each option. Once there were no further questions, I asked each person to write their level of agreement (1 to 4) with the proposal. The result was a mix of 1s and 2s. I then asked the 2s to share their reservations. Next, Amy explained her rationale for selecting that feature and thanked everyone for their input. We had a decision in just 15 minutes and moved on.

When the Product Manager is not the Decision Leader

There are times when the product manager is not the decision leader because of organizational or ownership issues.

I recently worked with an organization where the ultimate decision leader was the product steering committee, chaired by the VP of product and customer experience. The committee had several members so it was important to be clear what decision rule they would use to reach closure. They selected decision leader decides after discussion as the decision rule and the VP of product and customer experience was designated as the decision leader. Everyone involved in creating the strategy briefed the steering committee at the end of our launch planning workshop. The steering committee agreed to make a timely final decision within four business days of being briefed on the proposed launch plan.

There may be times when a product manager should delegate the decision to someone else who has greater expertise in the topic of the decision. For example the lead engineer could be the decision leader for topics on a product’s technical architecture.

Empowering the decision leader to choose the decision rule builds trust and accountability among the product team. A good decision-making process naturally builds a positive decision culture.

Steps for Making Collaborative Product Decisions

A product team can make collaborative product decisions with the “Decide How to Decide” framework and the two participatory decision rules as follows:

1. Frame the Decision

Identify the decision to be made and who the decision leader should be. For product decisions, it will most often be you, as product manager. You should provide your participants with all the necessary information about the decision: the purpose, timing, and available analysis, and ask them to prepare for the decision by completing a scoring matrix, effort/impact grid, or plus-minus-interesting-points list for the known options.

2. Explore Options

Participants should work together to explore alternatives, share views, and add analysis. They should review qualitative and quantitative data, such as interview findings or product metrics. The decision leader should assign small groups to work on the analysis or the use of prioritization tools (such as Kano analysis or a cost of delay calculation). One more thing: always timebox this step.

3. Make the Decision

When time is up for exploration or the group seems near closure, close the discussion, clarify the proposals for the decision, and poll the group using the gradient of agreement. It is always a good idea to ask anyone who polls at 2 (or higher) to briefly share the reasoning behind their degree of agreement.

Ultimately, you make the final decision. It is your responsibility to inform other stakeholders who were not decision participants of the reasoning behind your decision.

4. Analyze the Decision Retrospectively

Product retrospectives are one of the best ways to improve your decisions and to evolve your product culture. Always analyze product decisions retrospectively. This is an opportunity for reflection and learning. Hopefully, you’re conducting regular retrospectives and you incorporate the product decisions made as part of those retrospectives.

Building Trust

This collaborative process speeds up decision making, allows you to make better-informed decisions, and builds a healthy product culture. It promotes psychological safety and trust.

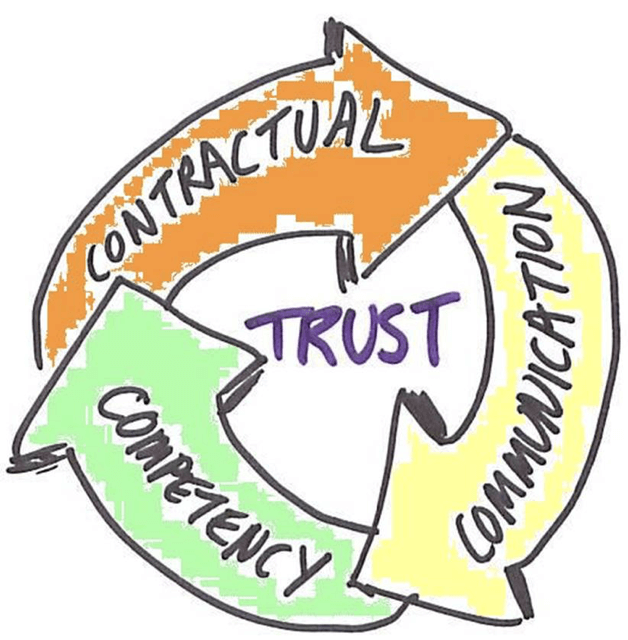

The “Decide How to Decide” process enhances trust among the product team. Reina and Reina identified that organizations need three types of trust: contractual, communication, and competence.

Contractual trust (trust of character) is based on an unstated contract:

“You will look out for my best interests, and I will look out for yours. If things change, we will renegotiate. Ultimately, we are jointly responsible for our success.”

Being transparent about your decision-making process builds contractual trust.

Communication trust calls for honest and frequent communication. Team members tell the truth, admit their mistakes, maintain confidentiality, and seek to provide feedback. Actions must be consistent with participants’ words and vice versa. A decision-making process that allows people to openly share their perspectives builds communication trust.

Competency trust (or trust of capability) occurs when product team members respect each other’s ability to get their jobs done. People promote mutual learning and development of everyone’s skills and knowledge. Engaging in participatory decision making demonstrates respect for the expertise of others. The building of competency increases mutual learning.

Healthy Decision Making Means Better Product Teams

Decision making requires the right decision-making process — deciding how to decide. When you are clear about product decision-making rules and engage the right people in the decision-making process, you get better decisions and better teams. When done well, your product decision process results in a culture of transparency and trust.

The post How to Make Product Decisions With Transparency and Trust appeared first on EBG Consulting.