As featured in: The Huffington PostHave you been in a yoga class wondering, “Why is my breathing so shallow?” Have you been singing or performing on stage and suddenly realized you’re running out of breath? Have you been exercising, or...

As featured in: The Huffington Post

Have you been in a yoga class wondering, “Why is my breathing so shallow?” Have you been singing or performing on stage and suddenly realized you’re running out of breath? Have you been exercising, or even texting, and noticed you’re holding your breath?

We limit our breath for many reasons. Maybe we are feeling overwhelmed, stressed or just lost in thought. Sometimes our breathing changes in anticipation or while holding in a difficult emotion. Essentially, breathing is a response to our activity and state of mind.

Shallow breathing or holding your breath is not exactly “holding” your breath, but it is interfering with the flow of life force and the potential motion of the diaphragm. It can also cause the respiratory muscles to weaken and lose their ability to move optimally.

When we notice a lack of breath, the common response is to inhale and take a deep, forced breath. Let’s look at the design of the respiratory system, and see what other more effective choices are available.

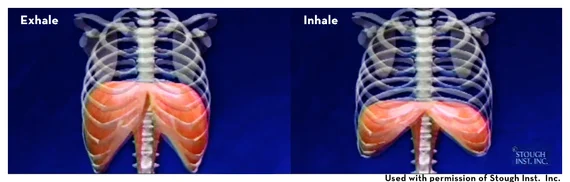

There is great potential for the diaphragm and the ribs to expand and contract as the lungs, which sit on top of the diaphragm, fill, and dispel air. Let’s take a look at the exhale first. The diaphragm (the orange muscle in photo above) is a dome-shaped muscle that rises to get the air out of the lungs as you breathe out. Then, it moves down to make room for the air as you breathe in.

It’s a common thought that inhaling is the important phase in the act of breathing, and people try to control it. Many say, “take a breath” or “tank up” when singing. I find that this controlled inhale can actually place unhealthy pressure on the diaphragm, often tensing neck and chest muscles that do not need to be overly involved in breathing.

Because most people are busy taking an in-breath, they do not pay much attention to the exhale process. Without exhaling completely, excess carbon dioxide — a known stressor in your nervous system — may remain in your lungs. The system detects that there is too much carbon dioxide and not enough oxygen. Then, it does the only thing it knows how to do: ask for more oxygen, causing another inhale. Since the lungs are still partially filled with carbon dioxide, not as much oxygen can get in. A cycle is set in motion and you keep inhaling for more oxygen, but can’t get enough because the lungs have not been properly emptied. This habit can lead to shallow breathing and holding your breath.

However, when you exhale completely, your body is designed to take a “reflex” inhale. By releasing your ribs and expelling all air in the lungs, you engage the spring-like action of your ribs to expand and create a partial vacuum, and the air comes in as a neurological reflex. This is what I call an optimal breath.

Optimal breath means you do not suck air in to “take” a breath or “push” air out to expel a breath. You allow air to flow in and out, so the lungs easily exhale carbon dioxide and effortlessly fill with oxygen. As your whole system slightly expands and contracts, your nervous system has the potential to settle and reduce stress.

So, next time you are in yoga class holding your breath while reading a text or email or you catch yourself interfering with the motion of the breathing cycle in any way, don’t force an inhale. Remember the potential movement of your ribs and diaphragm. Try putting your hands on the sides of your ribs and gently pushing your ribs down and in a tiny bit as you exhale and then let them spring open for your inhale. Be sure not to collapse your whole torso as you exhale, and instead, lengthen your spine.

Let your breath find its own rhythm. Nothing is as close to you as your own breath. Some breaths may be long and deep, and others shorter. Like the ocean waves, flowing in and out, all breaths are not the same.

The optimal breath brings fresh new oxygen to fill your whole torso and spread throughout your body to enhance life force. Then you can be present and able to engage in your next activity with full body, mind, spirit… and breath!

Check out my book, The Actor’s Secret, for many more of these exercises for personal and professional well-being and growth.

Betsy Polatin is a Movement and Breathing Specialist, Alexander Technique Teacher, Master Lecturer at Boston University, and the author of The Actor’s Secret distributed by Random House.