The best guideline is for all our government and civic institutions to respect the capacity of American citizens for freedom—our ability, whether in religion, the economy or in other human endeavors, to exercise our rights sensibly. The post Teaching...

At Teaching American History, we know teachers are hungry for resources that help their students understand the nuances of American civic behavior. For secondary and post-secondary government and political science educators, we are proud to recommend our CDC volume, Religious Liberty: Core Court Cases. Edited by Ken Masugi, Religious Liberty presents Supreme Court jurisprudence on the first guarantee of the Bill of Rights: freedom of religion, “the key element of republican citizenship.”

Download your free copy here. Below, we reprint an edited version of our 2019 interview with Professor Masugi. After describing his aims for the collection, he gives an historical account of the Supreme Court’s changing understanding of religious liberty.

How does this core document collection differ from other anthologies of Supreme Court cases?

What we have tried to do is not simply collect the most important opinions, as a law school “casebook” might, but to excerpt key cases reflecting important arguments that high school students—young citizens—ought to reflect on. That means developing a skill that is hard to come by for many students of government and politics: namely, seeing that strong arguments exist on both sides of controversial issues. And that there are often more than just two sides.

The first Supreme Court ruling excerpted in your collection was written in 1879. The second was written in 1943. You write that the Court did not begin applying the First Amendment’s establishment and free exercise clauses “to state and local laws until the mid-twentieth century.” Why did such cases not arise sooner?

The First Prayer in Congress, Sept. 1774. Created in 1860

The First Prayer in Congress, Sept. 1774. Created in 1860We should keep in mind that the Court examined these issues only after religious pluralism became the accepted reality for the country as a whole. It’s important to recall the language of the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” As Justice Thomas notes in many of his 14th amendment opinions, the Bill of Rights was originally intended to restrict actions of the federal government only. It was not intended to limit state support of religion, even taxation in support of particular sects. Such state laws would disappear by the 1830s due to the widespread belief in “equal protection” for all religions. As Federalist #51 argued, political freedom in the new republic would parallel religious freedom. And each would mutually reinforce the other.

Indeed, from the beginning of the republic the founding principles of equality and liberty promoted a generous understanding of religious freedom, as we see in Washington’s notable letter to the Hebrew congregation in Newport. Most religious groups, from the Jews of Rhode Island to the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut to the Moravians of Salem, North Carolina were able to worship and even organize faith-based communities without interference.

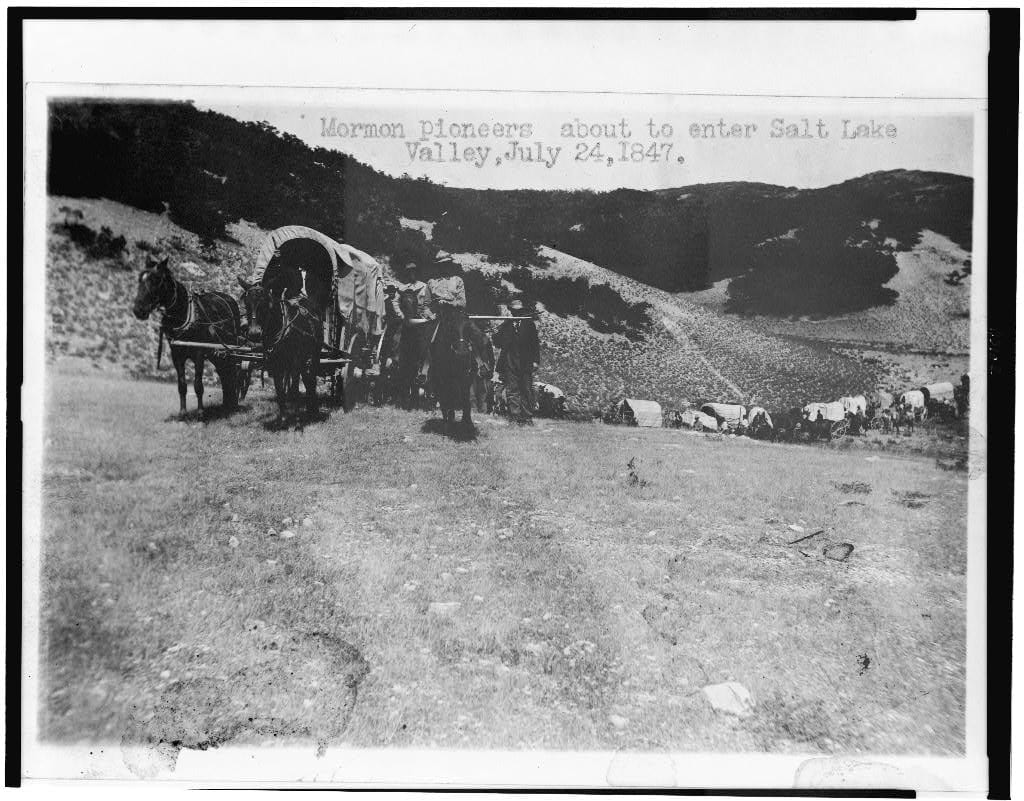

Mormon pioneers about to enter Salt Lake Valley, July 24, 1847. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-113102.

Mormon pioneers about to enter Salt Lake Valley, July 24, 1847. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-113102.Still, many Americans regarded at least one group, the Mormons, with suspicion and hostility, even directing violence against them. Their practice of plural marriage affronted Judeo-Christian morality and violated State and federal laws prohibiting bigamy. This led to the Court’s earliest ruling on the first amendment guarantee of free exercise. It tested whether Mormon polygamy was permitted under federal regulations on marriage in the territories. In 1879 the Court stood by the centuries-old understanding of marriage, ruling that religious freedom was bounded by basic legal traditions embodied in the common law.

The next cases that arose concerned religious practices that conflicted with the social customs of the larger community in the workplace, in commerce, or in schools—in particular, Sabbath observance on days other than Sunday. In these cases, the Court tended to grant minority claims. After 1938, the Court, citing the 14th amendment, acted to protect what it would identify as “discrete and insular minorities” who allegedly were being oppressed by democratic majorities and unable to defend their rights at the ballot box. Race was one obvious category, but the Court wanted to defend religious minorities as well. Religious minorities successfully sued against certain employment, Sunday closing, and school attendance laws.

Later the Court ruled against common practices such as the Pledge of Allegiance and voluntary prayer and even moments of silence, and not only in the classroom but in commencement exercises, in meetings held in classrooms after school hours, and pep rallies before high school football games. These practices were said to be establishments of religion. Dissenters on religion came to have a veto over community practices. Of course, prayers continue in many public high schools, as the dissenting justices predicted they would.

Beginning in the late 1940s and continuing through the early 2000s, the Court, led by Justices Black, Brennan, Stevens, and Souter, declared that the establishment clause was designed not just to guarantee equal protection of all religions but to prohibit preference for religion in general. Policies or institutions deemed religious could not be supported by taxpayer funds, for that would mean an establishment of religion. So, religious schools could not receive federal aid to supplement salaries—but might receive it to construct buildings or buy textbooks. The Court began making specious distinctions between various uses of federal or state dollars.

Russell Lee, “The school day opens with prayer at private school at the Farm Bureau building.” Pie Town, New Mexico, 1940 June. Library of Congress, LC-USF34- 036686-D.

Russell Lee, “The school day opens with prayer at private school at the Farm Bureau building.” Pie Town, New Mexico, 1940 June. Library of Congress, LC-USF34- 036686-D.Free exercise of religion became restricted to freedom to worship—that is, to religion only as practiced within a place of worship. This understanding of religion is far narrower than that of the founders, who acknowledged a public square full of Christians (not to mention Jews) openly professing a range of sectarian beliefs and organizing their lives in accordance with those beliefs.

Those who have objected to the currently ascendant constitutional argument, most notably former Justice Scalia, base their viewpoint on tradition and practice. Free exercise cannot extend to establishing an official church via the ballot box, but no religion is being imposed on anyone by Christmas decorations in a city hall. Justice Thomas argues there is no right to be shielded from encounters with others’ religious beliefs. Only if state coercion comes into play is there a constitutional case against a state practice concerning religion.

Justice Kagan has argued eloquently for the importance of opposing official endorsements of religion in civic practices and memorials such as public architecture. Her arguments leave certain questions unanswered. Does a cross commemorating fallen veterans violate the first amendment? Does the constitutionality of such a memorial rest on when it was built, whether just after World War I or just last year?

Your account brings to mind Washington’s comment in his Farewell Address that religion and morality are “indispensable supports” of self-government. How might the precedents on religious liberty differ if justices took Washington’s views into account?

President George Washington

President George WashingtonThe Justices are generally not great historians. I believe Washington’s views were held by the Court until the 1920s, when the Progressive view of American history began denigrating the founders as more concerned with their personal economic interests than with the public good.

Justice Stevens ignored history when he argued that the founders could not imagine Quakers, Jews, or Catholics enjoying the same religious freedom enjoyed by Protestants. Religious liberty extended to Catholics. Chief Justice Taney was Catholic, and there were politically prominent Catholics at the time of the founding, such as the Carroll family.

Over the years, justices have attempted to elaborate guidelines for determining violations of the religion clauses of the First Amendment. Do you find any particular guideline or approach more workable than others?

The best guideline is for all our government and civic institutions to respect the capacity of American citizens for freedom—our ability, whether in religion, the economy or in other human endeavors, to exercise our rights sensibly.

Just as we who live in the bureaucratic age should be more skeptical of governance by executive regulation, so should we be more skeptical of judicial rulings. Reading the justices’ words [carefully and critically may help] students become more vigilant citizens.

Finally, reflecting more calmly and deeply, cannot we Americans acknowledge that being human entails some kind of spiritual experience? Can we not then find in the holidays of Thanksgiving, Memorial Day, Martin Luther King Day—and yes, in the spirit of Christmas and Hanukkah—the rational basis for community, liberality, charity, and conscience that define the best in common citizenship?

The post Teaching the Bill of Rights: Religious Liberty appeared first on Teaching American History.