The economy boomed during the Roaring Twenties and rising incomes gave ordinary Americans access to enticing new conveniences, including washing machines, refrigerators, cars and other luxuries that would have once seemed unattainable. For a number of people, the idea of owning...

The economy boomed during the Roaring Twenties and rising incomes gave ordinary Americans access to enticing new conveniences, including washing machines, refrigerators, cars and other luxuries that would have once seemed unattainable. For a number of people, the idea of owning a car wasn’t enough. Such eagerness played right into the hands of the Roaring Twenties’ legions of fast-talking promoters, charlatans and outright swindlers, who enticed the would-be wealthy with scores of seemingly foolproof schemes—from stock companies that didn’t really exist, to speculation in Florida real estate or California oilfields.

In this article Richard Bluttal will examine the get rich quick schemes of the 1920s - which laid the foundation for the more elaborate ones of the 21st century.

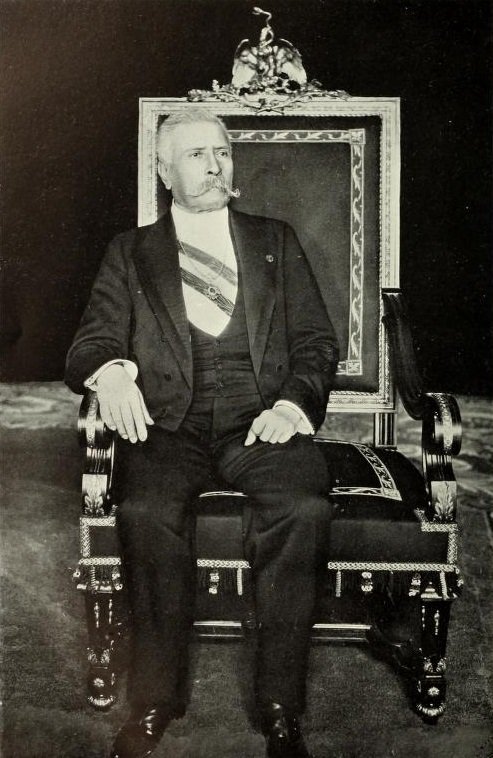

Charles Ponzi.

Charles Ponzi

Many people lacked the financial literacy to understand the difference between investing in a legitimate company and a scheme such as the one operated by Ponzi, an Italian immigrant who claimed to have become a wealthy man through sheer ingenuity and hard work.

Charles Ponzi was a dapper, five-foot-two-inch rogue who in 1920 raked in an estimated $15 million in eight months by persuading tens of thousands of Bostonians that he had unlocked the secret to easy wealth. Charles Ponzi was born Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi on March 3, 1882, in the town of Lugo in northern Italy. His parents, Oreste and Imelda Ponzi, Ponzi later said, were part of a wealthy Italian family that had become borderline poor by the time he was born. Ponzi is said to have expressed criminal tendencies early on, stealing from his parents and even parish priests.

As a young man, he attended Sapienza University in Rome, where, by his own account, he was less than a model student. As a result, after four years, Ponzi was forced to leave with no money and no degree. During his university years, he had heard stories of other Italians who went off to America to find fame and fortune and decided that this was the only course left open for him.

In 1919, after having set himself up in a small export-import business, Ponzi received a letter from a Spanish company requesting an advertising catalog. Inside the envelope, he found an iinternational reply coupon (IRC), a type of voucher accepted in various other countries in exchange for local postage stamps. Ponzi quickly realized the moneymaking potential of taking advantage of exchange-rate differences to buy IRCs in one country and redeem them in another.

In 1920, Ponzi organized a company called Securities Exchange Co. in which he sold stock (promissory notes) advertising 50% interest after 90 days. The funds obtained from investors were supposed to be used to buy IRCs to redeem in the U.S. Instead, Ponzi used funds obtained from new investors to pay off old investors. It was a big idea—one that Ponzi managed to sell to thousands of people. He claimed to have elaborate networks of agents throughout Europe who were making bulk purchases of postal reply coupons on his behalf. In the United States, Ponzi asserted, he worked his financial wizardry to turn those piles of paper coupons into larger piles of greenbacks. Pressed for details on how this transformation was achieved, he politely explained that he had to keep such information secret for competitive reasons.

By way of explaining why he did this, Ponzi blamed the Universal Postal Union for suspending the sale of IRCs once it learned about his coupon redemption scheme. After attempting to get around the suspension, Ponzi shifted to his “Rob Peter to pay Paul” scheme. For a while, it worked. He raked in $15 million ($220 million in 2022 dollars) in the first eight months of 1920. He kept the scheme going by telling investors he had created an elaborate network of agents buying IRCs for him overseas that he could redeem in the U.S. for a tidy profit. In fact, there was no elaborate network of coupon buyers; he was using new investments to pay off old investors.

In July 1920, the Boston Post ran a flattering front-page feature on Ponzi pegging his net worth at $8.5 million. Less than a week later, the U.S. Post Office Department announced new conversion rates for international postal reply coupons, though officials said the rate change had nothing to do with Ponzi.

Investigations of Ponzi ensued but made little progress until the Boston Post launched its own investigation, which generated bad press, causing Ponzi to decline to accept new investments. This caused a run by current investors, and Ponzi reportedly paid out more than $1 million.

More bad press from the Post ultimately sealed Ponzi’s fate. He was eventually convicted on federal charges of mail fraud and served 3˝ years in prison. Upon parole, he was convicted of state charges, jumped bail, was caught, and went to prison again, getting out in 1934. At that time, he was deported to his native Italy, having never become a U.S. citizen. His history in Italy and Brazil is not well documented, though it is known that he died on Jan. 18, 1949, in a charity hospital in Rio de Janeiro, leaving just $75 to pay for his burial.

Florida land boom speculators

By 1920, Florida had a population of 968,470 people. Just five years later, the population had grown to 1,263,540. Advertised as “heaven on earth,” Florida became the number one destination spot for upwardly mobile American families during the Roaring Twenties. In just five years, more than 200,000 Americans flocked south. What had caused such a rise in the population?

Following World War I, large numbers of Americans finally had the time and money to travel to Florida and to invest in real estate. Educated and skilled workers were receiving paid vacations, pensions, and fringe benefits, which made it easier for them to travel and to purchase real estate. The automobile was also becoming an indispensable way for families to travel, and Florida was the perfect destination. Many of the people who migrated into Florida were middle class Americans with families. Unlike visitors of the past, these newer arrivals wanted homes and land rather than resorts and hotels. Moguls bought up cheap land, advertising accommodations-to-come through bold announcements across the country. Developers rushed to transform Everglade swamps into resort towns, like Miami Beach and Tampa Bay.

During this boom, however, most people who bought and sold land in Florida had never even set foot in the state. Instead, they hired young, ambitious men and women to stand in the hot sun to show the land to prospective buyers and accept a "binder" on the sale. The binder was a non-refundable down payment that required the rest of the money to be paid in 30 days. Many people got rich quickly from the commission they made from these sales. With land prices rising rapidly, many of the buyers planned to sell the land at a profit before the real land payments were due. Sometimes land buyers didn't even have enough money to pay for the land; instead, they had just enough money for the binder. They were depending on the prices to continually rise.

It was during this time that many vacation spots were created and some of our most popular cities were developed. Dave Davis, the son of a steamboat captain, built Davis Island in the Tampa Bay area. Barron Collier started Naples and Marco Island as winter resorts. There were so many characters and stories of the boom times. There’s D. P. Davis, who in 1924 sold 300 building lots in Tampa Bay in three hours — while they were still underwater — and who remarried his first wife because, his brother said, he wanted to make his mistress jealous. There’s Barron Collier, who developed 1.2 million acres of southwest Florida that made him, if you could believe the price tags he put on them (and many thousands did), richer than John D. Rockefeller. The society architect Addison Mizner spun a fairyland of neo-Spanish castles in Palm Beach. His con man brother Wilson prophetically said, “Easy street is a blind alley,” and not much later the two of them found themselves stumbling along its darkened length.

Unfortunately, this land boom did not exist without problems. The demand for housing was so high that the cost of rent soared. Because the speculators had inflated the economy, many Americans who had migrated to Florida could no longer afford to live here. They began to write back home and tell people about their problems. Newspapers began writing stories that advised prospective residents to stay away from Florida.

At the same time, the demand for building materials overwhelmed the railway systems that transported them here. Railroads could not keep up with the needs and began to shut down. This acted as a brake on many developments, slowing down or stopping the boom's momentum. Once land prices stopped going up, many speculators couldn't sell at the high prices. There were suddenly thousands of acres of overpriced land without any buyers.

The boom stopped as suddenly as it had started. An unusually cold winter in 1925 followed by an extremely hot summer frightened away many potential buyers. It also cast doubts on the state's reputation as "heaven on earth." What was to follow was a series of natural disasters (freezes, hurricanes) that would send Florida into a tailspin, causing it to enter a Florida Depression four years before the 1929 stock market crash brought the whole country's economy down in the Great Depression.

Chauncey C. Julian

In the Roaring Twenties, this oil stock swindler dressed to the nines while boasting to small investors that his sham oil-drilling operations would yield easy 30-to-1 returns. His specialty was writing newspaper sales pitches that used folksy, plainspoken language. Julian became a millionaire, chiefly by selling more shares in his worthless syndicates than existed. When his empire began to crumble, Julian fled to Shanghai. One night in 1934, he arranged a banquet in his own honor, excused himself, and went upstairs to his hotel room to drink a suicidal dose of poison.

Charles A. Stoneham

The inveterate gambler was known in the 1920s for allegedly winning against the New York Giants baseball team in a game of poker. On Wall Street, he specialized in “bucket shops,” cut-rate brokerage houses that dangled low commissions as means to obtain money the firm almost never invested or repaid. Individual stock orders would be entered into the books but not filled on the open market. Instead, they would be “bucketed,” or combined into larger blocks that would be traded only if prices favored the brokerage. Despite his close association with Arnold Rothstein, the gambler who reportedly fixed the 1919 World Series, Stoneham was never sanctioned by Major League Baseball. The only time he was ever brought up on stock fraud charges, he was acquitted amid allegations of jury tampering.

Radio Pool

The 1920’s was the last decade before the onset of the Securities and Exchange Commission. As a result, stock manipulation was virtually legal, and was performed by pools of investors who traded large blocks back and forth in consortium with each other to drive the price of certain stocks up substantially. One such group, the Radio Pool, traded Radio Corporation of America (RCA) stock until the price rose from $100 per share in 1928 to over $500 per share just before the big crash. The pool then sold out and left the vast number of smaller shareholders with huge losses just in time for the stock market to crash in October 1929. With the advent of the depression and ensuing regulations, the investor pool collaboration was among those activities that were outlawed.

Joseph “Yellow Kid” Weil

Long before Notre Dame football star Manti Te'o said he was duped by an imaginary Internet girlfriend, Joseph "Yellow Kid" Weil was plucking the gullible. A regular entry on Chicago police blotters in the first half of the 20th century, Weil was dubbed the "king of the con men" by reporters who eagerly chronicled his nefarious schemes. He brought out the poet in headline writers. A 1924 Tribune story was titled: "Weil Loses His Sangfroid as Accuser Glares."

The lead paragraph wasn't too bad either. He was described as a "debonair fast talker who plants in the provinces and reaps in the cities" — a reference to Weil being an equal-opportunity swindler who fleeced country bumpkins and city slickers alike. In his later years, he worked the local, off-beat lecture circuit, claiming to have taken suckers for a total of more than $8 million. Yet when he died in 1976 at the age of 100, the Kid was virtually a pauper, leaving an estate of $195 in the form of a credit at the Sheridan Road nursing home that was his final address.

When the Lake Front Convalescent Center threw a party for Weil's 99th party, he told a Tribune reporter he had no regrets about what he had done with his life. "I'd do it the same way again," he said. Sometimes he claimed to be not a victimizer but a victim of reporters giving free rein to their imaginations in order to sell papers.

According to the Tribune, he told one judge: "The dastardly fabrications of the metropolitan newspapers, the reprehensible conduct of journalists to surround me with a nimbus — er — a numbus of guilt, is astonishing." Yet in his "Autobiography of a Master Swindler," he acknowledged his chosen profession, even as he bemoaned its decline. "There are no good confidence men anymore," he wrote, "because they do not have the necessary knowledge of foreign affairs, domestic problems, and human nature."

He certainly demonstrated more than a smattering of knowledge of those fields. He characterized the psychology underlying his working methods much as a judo wrestler explains how he turns his opponent's strength against him. He said: "A chap who wants something for nothing usually winds up with nothing for something." On other occasions, he defended his swindles with a Robin Hood twist. "He said he 'never took a dollar from a man who didn't deserve to lose it' because of greed," the Tribune recalled in Weil's obituary.

During World War I, Weil and his longtime confederate Frederick Buckminster swindled a Kokomo, Ind., banker out of more than $100,000, duping him "into purchasing fake stock in an Indiana steel mill by posing as representatives of German interests at a time when German ownership of American securities was embarrassing," the Trib noted.

Bankers were a favorite target of Weil, who took a Fort Wayne, Ind., banker for $15,000 in a 1917 scheme in which a confederate posed as an Englishman. A year later, Weil had no less than six phony brokerage offices up and running, their supposed bona fides supported by fake letters on counterfeit stationery of J.P. Morgan & Co. "We have learned of several letters bearing the supposed signature of Mr. Morgan," an assistant state's attorney told a Tribune reporter.

But Weil was not above fleecing at the other end of the economic ladder. Under a 1949 headline: "The Yellow Kid Beats $3 Case by Technicality," the Tribune reported he pocketed a $3 check solicited on behalf of the Little Sisters of the Poor. Weil told the judge he'd be happy to give the nuns the money. "And I would have been happy to give you a year in the Bridewell (a nickname for jail) if the case had been submitted to me on the proper charge," the judge told Weil.

Like many other areas of his life, the story of Weil's nickname had several versions. It was attributed to his fancy-dan attire, a supposed taste for yellow gloves, spats and vests, an etymology Weil denied in his autobiography. Others credit it to "Bathhouse John" Coughlin, a turn-of-the-20th century alderman and protector of vice operations in Chicago's red-light district. Apparently "The Bath" hung the moniker on Weil in 1901, borrowing it from a comic strip of the day, "Hogan's Alley and the Yellow Kid."

Weil was, in his own way, civic minded. In 1928, doing time in the Leavenworth, Kan., federal prison, he sent letters to Chicagoans appealing for funds so fellow inmates might properly celebrate Passover. He signed the letter: "Joseph Weil, president Jewish congregation."

He also felt strongly that there was a pecking order among gentlemen thieves, and Weil had nothing but contempt for one peer. In 1949, one Sigmund Engel, called "Chicago's marrying swindler" for defrauding women over a five-decade career, finally was being charged. As Weil commented, his "neatly trimmed mustache and parted beard fairly bristled," the Tribune noted. "There isn't a day that someone doesn't abscond with a woman's money," Weil said. "Preying on the love of women for money is one of the most despicable ways of making a livelihood I ever heard of."

Though he could be proud, he wasn't above taking a blow to the ego — if it might save him from a stint in the clink. When Weil was charged in 1925 with writing a bum check, a court-appointed doctor from the "psychopathic laboratory" found the Kid had the intelligence of a 16-year-old. "He is foppish to the last degree, a moral imbecile, possessed of a busy brain that is eternally plotting against somebody but unaware that injury is being done to others," the psychiatrist told the judge.

Weill seconded the motion. "I can't defend myself," he told the judge. "Why the very learned Dr. Hickson says I have the mentality of a child of sixteen." He was sentenced to 30 days in jail.

And he could wax philosophically on the vagaries of human existence, as in 1925, when he lost a Sheridan Road hotel, he owned for failing to make his loan payments.

"Life is a funny proposition, after all," he told a Trib reporter. "We are born, we live a while, and then someone forecloses the mortgage."

Did you enjoy the piece? If so, join us for free by clicking here.