When I visited Rosy Galván Yamanaka’s home in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, she had a bowl of Mexican-style udon prepared for me. I sat down in her dining room and listened as she told me stories of her grandfather, José...

When I visited Rosy Galván Yamanaka’s home in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, she had a bowl of Mexican-style udon prepared for me. I sat down in her dining room and listened as she told me stories of her grandfather, José Ángel Yamanaka, a Japanese migrant who arrived in Mexico at the beginning of the twentieth century. Like many other Japanese migrants, Yamanaka arrived to work in the coal mines of Coahuila. Eventually, he settled in Piedras Negras. This city on the Texas-Mexico border is not just a place with a community of Japanese Mexicans, it is also a border town currently witnessing the arrival of large groups of Honduran, Venezuelan, and other migrants. Though not apparent at first, the overlooked histories of Japanese communities in Mexico and Texas during WWII and the stories of migrants at the border today highlight similar experiences of exclusion, criminalization, and violence.

Rosy (on the right) pictured with her mother (center) and younger brother (left) during a visit to her grandfather’s home in Monclova, Coahuila. Courtesy of Rosy Galván Yamanaka.

Rosy (on the right) pictured with her mother (center) and younger brother (left) during a visit to her grandfather’s home in Monclova, Coahuila. Courtesy of Rosy Galván Yamanaka.After recalling she possessed a few photographs of her family from 1942 to 1945, Galván Yamanaka began telling me how her grandfather had relocated to Monclova, Coahuila, during the war. Her grandfather had moved south to Monclova after Mexican President Manuel Ávila Camacho ordered all Japanese living near the border to relocate to Mexico City and Guadalajara. The Yamanaka family was separated for three years but they were fortunate to be in the same state. Other Japanese Mexican families were not able to visit their relatives due to costs and long distances. Galván Yamanaka is aware that her grandfather was forced to leave Piedras Negras and relocate to Monclova during the war because she was born in 1941, at the start of the war. She carries these stories of the war time years because of the time she spent with her grandfather and older family members and she believes it is her duty to share them with the younger generations in her family.

Japanese Mexican memories of WWII are often obscured. Some Japanese-Mexican families do not know what happened to their family members during the war. For many, it took years to discover why their families were forcibly separated by the Mexican state regardless of their Japanese relatives’ citizenship. These memories of war then remain within each Japanese Mexican family. Some Japanese Mexican families do not know about the discrimination faced by their relatives and that they were forced to leave their homes. In fact, most Mexicans are unaware of this part of Mexican history.

In January 1942, President Ávila Camacho ordered all Japanese migrants and Japanese-Mexican communities near the Pacific coast and the U.S.-Mexico border to relocate to central Mexico. The Mexican government gave Japanese Mexicans 24 hours to evacuate and move to Guadalajara and Mexico City. The government also stopped accepting naturalization applications from Japanese migrants and prevented Japanese nationals and Japanese Mexicans from collecting funds from banks or making any money exchanges.[1] The government’s response to the Pearl Harbor attack of December 1941 targeted Japanese communities near the U.S.-Mexico border and the Pacific Coast as these communities were marked as a “threat” to both the U.S. and Mexico.[2] Japanese Mexicans were responsible for organizing their own travel to Central Mexico and reporting their relocation to the government. Unlike some countries in Latin America, the Mexican government did not work with the U.S. government to deport its Japanese communities to camps in the U.S.[3]

The stories of Japanese incarceration in the U.S. and the forced removal of Japanese Mexicans are often not told together, obscuring the ways both the Mexican and American governments were complicit in the racialization and criminalization of Japanese communities during the war.[4] By telling transborder stories of WWII, we learn Mexican intelligence agencies, along with the FBI, the Border Patrol, Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS), and local law enforcement in Texas-Mexico border, were part of the relocation, removal, and policing of Japanese nationals and Japanese families from the border region. These narratives not only include northern Mexico and Texas in histories of Japanese exclusion and policing during the first half of the twentieth century, but they also illustrate how collaborations between agencies and officials in the U.S. and Mexico have long affected immigrant communities at the border.

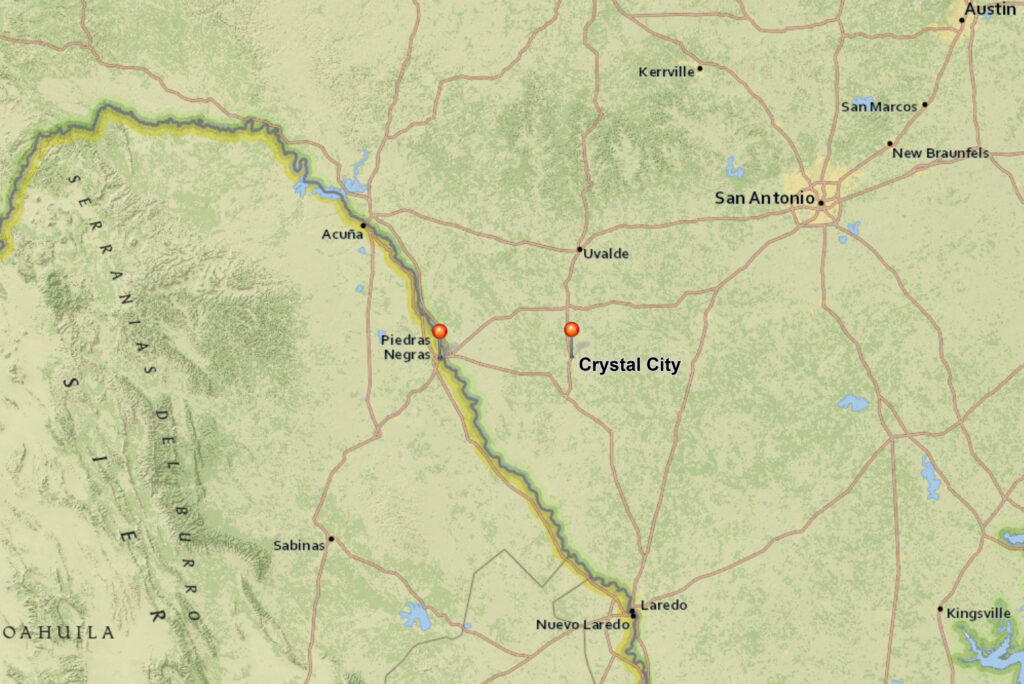

US-Mexico border map

US-Mexico border mapFor instance, the Crystal City camp in Texas, which opened in 1942, was located 50 miles east of Eagle Pass-Piedras Negras. It was used to hold Japanese Americans, Japanese Latin Americans, and other incarcerees of Italian and German descent. This camp was operated by Border Patrol and INS agents. Still, this history of Japanese incarceration is not often remembered within the histories of criminalization and exclusion in South Texas and the U.S.-Mexico border region. The presence of this Japanese incarceration camp in South Texas, like the displacement of Japanese Mexican communities in northern Mexico, is also not part of the regional communities’ memories. Both cases uncover hidden narratives of surveillance and policing of Japanese communities at the border that began decades prior to WWII.[5] These histories also reflect a longer history of family separation as families of Japanese Americans, Japanese Mexicans, and Japanese Latin Americans were split from their families and forced to move across state and national borders.

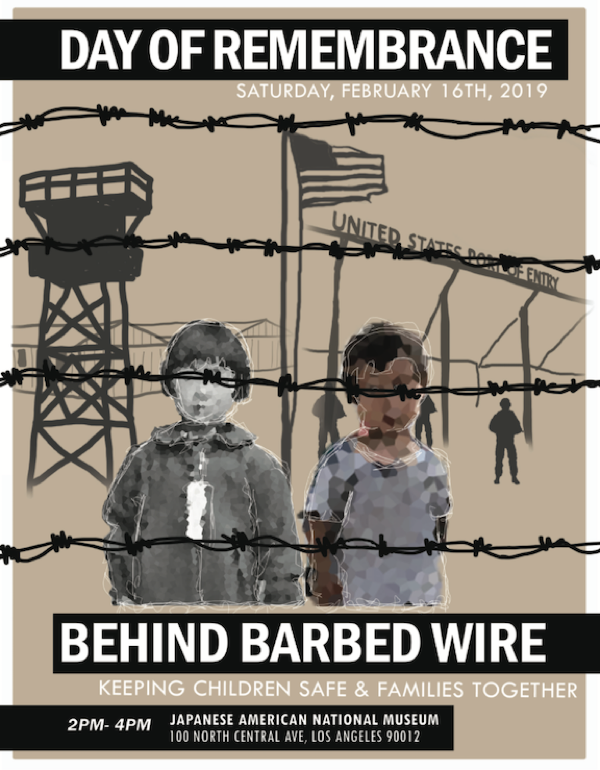

“Behind Barbed Wire” poster for the Japanese American National Museum’s Day of Remembrance in 2019. Courtesy of the JAMN (https://www.janm.org).

“Behind Barbed Wire” poster for the Japanese American National Museum’s Day of Remembrance in 2019. Courtesy of the JAMN (https://www.janm.org).Today, artists and community organizations are highlighting the convergence of past and present forms of incarceration and policing through their work. This drawing by Japanese-American artist Elyse Imoto illustrates the similar criminalization and violence experienced by Japanese communities during the war and of Mexican, Central American, Haitian, Venezuelan, and other migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border in recent years.[6] The juxtaposition of one child in black and white and another in color marks a past and a present. One child is painted in black and white and resembles a young Japanese-American girl held during the period of Japanese incarceration in the 1940s. The second child pictured on the right is depicted in color and resembles a young Mexican or Central American child at the U.S.-Mexico border in the present. The background includes a watchtower, buildings that were typically found in incarceration camps, and a “United States Port of Entry” sign with figures that resemble armed Border Patrol agents.

Migrant detention has been on the rise since 2016, and as of August 2022, there have been 372 cases of family separation since 2021.[7] Cases of family separation at the border are a result of policies that criminally convict migrants and separate any parents or adults crossing with children. One might not immediately think the conditions and treatment of migrants on the U.S.-Mexico border today are related to the treatment of Japanese communities and their forced removal during the war. However, those incarcerated in the Crystal City camp and Japanese Mexicans living in the states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas were forced to relocate and leave their families and communities behind. The history of Japanese displacement during WWII is seen as distant from the Texas-Mexico border and not related to larger histories of incarceration and violence in the region. Yet, the migrant experiences in South Texas are part of a continuous normalization of violence that is deemed acceptable by the state through its language and policies for “national security” or against possible “threats” or “criminals.” Japanese incarceration near the Texas-Mexico border and the current state policies related to migration and citizenship at the U.S.-Mexico border are part of a process of exclusion that developed as a result of racialized immigration and enforcement policies of the twentieth century.

Courtesy of Tsuru for Solidarity (https://tsuruforsolidarity.org)

Courtesy of Tsuru for Solidarity (https://tsuruforsolidarity.org)In the U.S., groups like Tsuru for Solidarity are trying to change this by sharing their experiences and the stories of family separation during WWII to #StopRepeatingHistory.[8] Tsuru for Solidarity is a project that is made up of Japanese American and Japanese Latin American social justice advocates and their allies, and the group leads campaigns across the U.S. to educate the public on the history of Japanese incarceration and build solidarities with other groups that are targeted by racist immigration policies. Some of the participants are members of the Japanese families that were incarcerated during the war or descendants of former incarcerees. They lead campaigns outside of immigrant detention centers across the U.S. to protest conditions in these centers and policies like family separation.

The history of Japanese incarceration, forced removal, and family separation during the war on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border illustrate the legacies of violence that have longer ties to anti-Asian exclusion in the late 19th century. The legacy of these policies reverberates into the present with the criminalization and incarceration of migrants and asylum seekers on the U.S.-Mexico border. Descendants of Japanese families and community activists in the U.S. and Mexico are sharing their memories within their families and communities, thus making sure these stories are not forgotten.

Lucero Estrella is a PhD candidate in American Studies at Yale University, and she is currently a Visiting Research Affiliate at the Institute for Historical Studies (IHS) at UT Austin. Her dissertation is a study of the histories of Japanese migration and community formation in Texas and northeastern Mexico across the 20th century. Her dissertation examines how Japanese mining and farming communities in Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Texas are critical to histories of race, migration, and empire. Using oral histories with Japanese communities on both sides of the border and sources from state and local archives in Mexico, Japan, and the U.S., her work illustrates how Japanese Americans and Japanese Mexicans, and the national and global forces that structured their lives, shaped the histories of Mexico, Japan, Texas, and the U.S.-Mexico border region.

[1] María Elena Ota Mishima, Siete migraciones japonesas en México 1890-1978. (México: El Colegio de México, 1982), 97.

[2] The surveillance of Japanese communities in northern Mexico was not new, and U.S. surveillance of Japanese settlements in Mexico between the 1920s and the 1940s were fueled by U.S. state anxieties over the expansion of Japanese empire and fear of “yellow peril.” See the works of scholars Eiichiro Azuma, Jerry Garcia, and Sergio Hernández Galindo for more: Sergio Hernandez Galindo, La guerra contra los japoneses en Mexico durante la segunda guerra mundial: Kiso Tsuru y Masao Imuro, migrantes vigilados, First edition. (Mexico City: Itaca), 2011; Jerry Garcia. Looking like the Enemy: Japanese Mexicans, the Mexican State, and US Hegemony, 1897-1945. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2014; Azuma, Eiichiro. “Japanese Immigrant Settler Colonialism in the U.S.-Mexican Borderlands and the U.S. Racial-Imperialist Politics of the Hemispheric “Yellow Peril”.” Pacific Historical Review 83, no. 2 (2014).

[3] Countries like Peru, Panama, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Venezuela worked with the U.S. to forcibly deport and incarcerate Japanese Latin Americans in camps in the U.S. Some Japanese living in Mexico, such as high-level officials, diplomats, and a small number of Japanese nationals and Japanese-Mexicans living near the border were incarcerated in the U.S. For more on Japanese incarceration in Mexico see Selfa A. Chew, Uprooting Community: Japanese Mexicans, World War II, and the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2015).

[4] Scholars have debated the use of “internment” and “incarceration” among other words like “detention” and “confinement.” Densho, a Japanese American non-profit organization based in Seattle, “encourage the use of “incarceration,” except in the specific case of Japanese Americans detained by the Army or DOJ.” Historian Connie Chiang notes that incarceration conveys the lack of freedom faced by those of Japanese ancestry and I use “incarceration” for this reason. See “Terminology – Densho: Japanese American Incarceration and Japanese Internment.” Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project. https://densho.org/terminology/#incarceration; Connie Y. Chiang. Nature Behind Barbed Wire: An Environmental History of the Japanese American Incarceration. (Oxford University Press. 2018).

[5] Concerns over Japanese and other Asian migrants bypassing immigration restrictions and crossing the U.S.-Mexico border to enter the U.S. extended across the border into Northern Mexico and were fueled by a transborder Yellow Peril. These concerns were not only about unauthorized Japanese immigration into the U.S. but also about large Japanese colonies forming in Mexico and Japanese purchasing large concessions in Mexico. See Eiichiro Azuma, “Japanese Immigrant Settler Colonialism in the U.S.-Mexican Borderlands and the U.S. Racial-Imperialist Politics of the Hemispheric ‘Yellow Peril,’” Pacific Historical Review 83, no. 2 (2014): 255–76.

[6] This drawing by Imoto was used as the poster for the Japanese American National Museum’s Day of Remembrance in 2019. This was used as the cover to their program as well as the image used to promote the in-person event hosted at JANM in Los Angeles.

[7] “Biden is Still Separating Migrant Kids from Their Families.” Texas Observer. November 21, 2022. https://www.texasobserver.org/the-biden-administration-is-still-separating-kids-from-their-families/.

[8] For more on Tsuru for Solidarity and their campaigns and efforts see: https://tsuruforsolidarity.org.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

The post Memories of War: Japanese Borderlands Experiences during WWII appeared first on Not Even Past.