This is a guest blog post by Amelia Yeager (she/her), a first year Master’s student in public history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where she studies free and unfree labor in early America and the legacies of rural...

This is a guest blog post by Amelia Yeager (she/her), a first year Master’s student in public history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where she studies free and unfree labor in early America and the legacies of rural labor and craft in cultural history. Amelia is a 2023 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

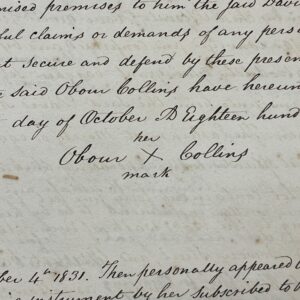

One of the rare traces of Obour Collins in the documentary record: a copy of her mark on a deed of sale from 1831. At the time, she was too old or infirm to sign her name. Newport Probate 18:356-357.

In this post, I refer to Obour Tanner by the surname of her enslaver, which was used in her correspondence with Phillis Wheatley. After her marriage, Tanner took her husband’s surname, Collins. Because “Obour Tanner” is the name in her correspondence during the period in question, and because it is the name by which she is known in public scholarship, I have chosen to refer to her as Tanner in subsequent mentions.

On July 10th, 1768, a young woman was baptized in Newport’s First Congregational Church. Her name was recorded as “Obour Tanner, servant of James Tanner.” Just below it reads “died June 21 1835” — this single line bookends the life of Obour Tanner in the documentary record.[1] Because nothing in her own hand has surfaced, much of what we know about Tanner comes from her friend, Phillis Wheatley, who was an African poet enslaved in Boston. Brilliant, multilingual, and well-educated, Wheatley became the first African American to publish a book of poetry in 1773. The two friends were each kidnapped from Western Africa as children and enslaved in New England, both were literate, and both would later be freed and go on to marry free men. Why is it, then, that we know so much about the details of Wheatley’s life and so little about Tanner’s, even though she outlived her friend by more than 50 years?

The first of the seven surviving letters between the two — all written by Wheatley to Tanner — is dated July of 1772 and suggests that they had already been well acquainted: it’s signed “your affectionate friend, & humble servt., Phillis Wheatley.”[2] At the time, Wheatley would have been 19, and Tanner would have been about 22; it’s possible the two met while the Wheatleys, Phillis’s enslavers, made a visit to Newport.[3]

Among the Newporters mentioned in the correspondence is Tanner’s “Pastor’s Son”, referring to a son of Rev. Samuel Hopkins, who had been the pastor at First Congregational Church since 1770.[4] Wheatley later trusted Tanner’s loyalty and connections enough to ask her to gather subscriptions for her first and only published book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.[5] In 1774, Hopkins purchased a volume for the First Congregational Church.[6] Tanner’s own personal copy was likely part of his 20-book order — Wheatley asked him to set aside two copies for “Ms. Tanner.”[7]

Obour Tanner’s baptism and death are recorded on the same line, 67 years apart. First Congregational Church, Marriages and Baptisms, 1744-1825 Vol. 832, page 27. NHS Collection.

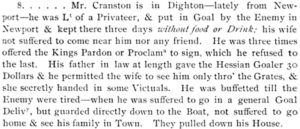

Letters in May of 1778 and 1779 are addressed to Obour Tanner in Worcester, where she had relocated with the Tanner family presumably to escape the British occupation of Newport. Wheatley suggests that the move was somewhat sudden: “I am exceedingly glad to hear from you by Mrs. Tanner,” she wrote in 1778, “and wish you had timely notice of her departure, so as to have wrote me.”[8] One year later, in the last letter to surface between the two, Wheatley laments that their communication has become less frequent, alluding to the upheaval of the Revolution: “I hope our correspondence will revive — and revive in better times.”[9]

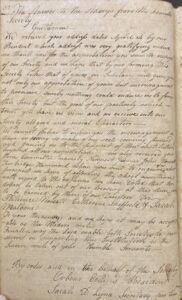

Obour Collins (Tanner’s married name) is listed as president of the AFBS in this page from the ABS meeting minutes. Vol.1647A, page 33, NHS Collection.

It remains unclear whether their correspondence did revive, or how much better times became for Tanner. In 1790, she married Barra Collins, a free Black man (Rev. Samuel Hopkins officiated), and by 1809, she was president of the African Female Benevolent Society.[10] Like many others in Newport’s free Black community, though, the hardships of displacement would have endured.

The correspondence carries one more revelation, this one penciled onto the donation note by Katherine Edes Beecher, wife of the pastor of the First Congregational Church from 1830-1833. In a rare description, Beecher, who obtained the letters not long before Tanner’s death in 1835, characterized her as “a very little, very old, very infirm, very, very black woman… an uncommonly pious, sensible, and intelligent woman, respected and visited by every person in Newport who could appreciate excellence.”[11]

While Beecher’s description provides a sense of Tanner later in life, only in exceptional cases like Wheatley’s did enslaved people have opportunities to garner a reputation on their own terms. For the majority of enslaved people, especially women, their ideas and accomplishments are neglected in the documentary record in an omission symptomatic of American slavery and its legacy. This doesn’t mean, though, that Tanner and other underrepresented Newporters are destined for obscurity. Revelations from archives, collections, and objects are emerging, and hopefully, the lives of enslaved and freed people will continue to come into focus for twenty-first century audiences.

[1] First Congregational Church, Marriages and Baptisms, 1744-1825 Vol. 832, page 27. NHS Collection.

[2] Phillis Wheatley, “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Obour Tanner, 19 July 1772,” July 19, 1772, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=773&img_step=2&br=1&mode=transcript#page2.

[3] Tanner’s age is an estimate based on the custom of baptizing enslaved people when they turn 18. If the Tanners followed this custom when they baptized Obour Tanner in 1768, it would put her birth year at 1750, just three years before Wheatley’s.

[4] For more on Hopkins’ communications with Wheatley, see Tara Bynum, “Chasing Phillis Wheatley,” The Hedgehog Review 23, no. 3 (Fall 2021), https://hedgehogreview.com/issues/authenticity/articles/chasing-phillis-wheatley.

[5] Phillis Wheatley, “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Obour Tanner, 30 October 1773,” October 30, 1773, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=773&img_step=2&br=1&mode=transcript#page2.

[6] First Congregational Church records, MS.123 Box 1 Folder 19, NHS Collections.

[7] Wheatley, Phillis. “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Samuel Hopkins, 9 February 1774,” February 9, 1774. 13755. Simon Gratz collection. https://digitallibrary.hsp.org/index.php/Detail/objects/13755.

[8] Phillis Wheatley, “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Obour Tanner, 29 May 1778,” May 29, 1778, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=777&br=1.

[9] Phillis Wheatley, “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Obour Tanner, 10 May 1779,” May 10, 1779, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=778&br=1.

[10] First Congregational Church Record Book, vol. 832:17. Newport Historical Society; “Minutes of the African Benevolent Society, 1807-1824” (Newport Historical Society), VOL.1674A, Free African Union Society and African Benevolent Society Records, https://collections.newporthistory.org/Detail/objects/12507, 33.

[11] “November Meeting,” 268-269, footnote.

The post History Bytes: Reading between the Lines for Obour Tanner appeared first on Newport Historical Society.