This is a guest blog post by Lindsey Smith (she/her), a recent graduate of Salve Regina University with a BA in history (concentration in American history). Lindsey is a 2023 John E. McGinty Fellow. The civil rights struggle involved...

This is a guest blog post by Lindsey Smith (she/her), a recent graduate of Salve Regina University with a BA in history (concentration in American history). Lindsey is a 2023 John E. McGinty Fellow.

The civil rights struggle involved an interconnectedness between northern and southern Black activists, radical groups, and religious organizations, particularly during lunch counter demonstrations.[1] Through nonviolent direct action, teachers, students, and activists carefully orchestrated protests at department stores which allowed Black customers to purchase goods but refused to serve them at lunch counters. While “sit-ins” had been occurring for some time, the highly publicized protests at the Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina beginning in February 1960 caused a sweeping movement across the nation. By early 1960, participating groups worked in tandem across regional boundaries to uproot segregationist systems.[2] The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) urged Black Americans across the nation to boycott chain stores that refused to allow them to sit at lunch counters alongside white patrons. Intended to place economic pressure on businesses, this tactic was presented after hundreds of protestors in the south faced imprisonment and fines for patronizing segregated restaurants.[3] Young, ambitious, highly motivated students across the country felt, according to Lyle E. Matthews, former president of the Newport branch of the NAACP, “95 years of waiting is time enough.”[4] Members of the NAACP in Newport were no exception.

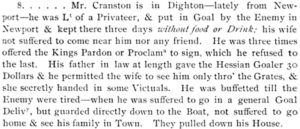

Article on the protests organized by the Newport branch of the NAACP, published by the Newport Daily News on March 29 1960.

At the urging of the New England regional conference of the NAACP, the Newport chapter resolved to hold demonstrations in alliance with the widespread sit-in movement. The organization gathered in the home of former branch president Matthews and agreed to halt patronage at stores that maintained segregated policies in the south.[5] A meeting of around fifty members of the branch solidified their decision at the Colored Odd Fellows Hall at 21 Caleb Earl Street in Newport.[6] The local branch notified the department stores it sought to protest, including the W.T. Grant Company stores in Newport and Middletown and the F.W. Woolworth’s in Middletown, Rhode Island.[7] The sitting president of the Newport branch, Ermino P. Lisbon, reasoned that the decision to boycott was not a consequence of unequal treatment in the department stores in Rhode Island, but as a result of segregated policies of service by store affiliates in southern states.[8]

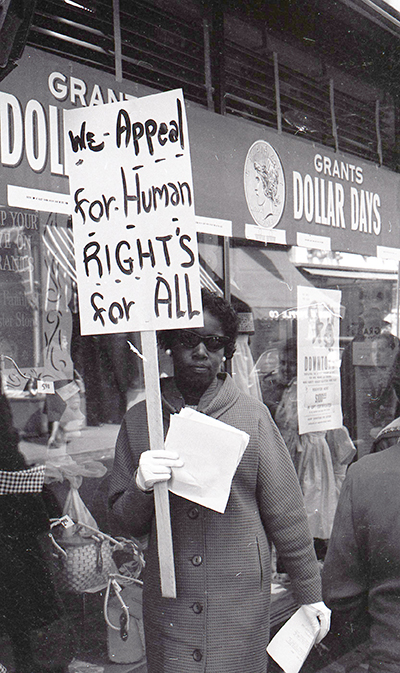

Picketing the W.T. Grant Company store on Thames Street in protest of its segregationist policies. April 2, 1960. 2018.015.216, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

On Saturday April 2, 1960, two dozen members of the Newport branch of the NAACP gathered outside of the local W.T. Grant Company store on Thames Street, with picket signs reading “Negro students denied a cup of coffee,” and “One nation with liberty and justice for whom?”[9] Among those protesting on Thames were Ermino Lisbon, Ernestine Lomax, and Elaine Parker. Reverend Alvin J. Simmons of the Mt. Zion African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Newport led the demonstrators at the Woolworth entrance in Middletown. Similar to southern protests against segregation, established Black leaders from churches and political organizations and students from the University of Rhode Island acted as organizers. The demonstrations were approved by the police chief of Newport, and were largely peaceful and orderly.[10] The participation of northern Black citizens in the boycotts brought national attention to the indignities suffered by Black Americans in the south. Application of economic pressure on chain stores across the nation successfully led to a wave of integration of lunch counters as early as the summer of 1960.

Through highly organized civil disobedience, the Black community in Newport expressed commitment to rectifying the national problem of inequality. While activists in Newport campaigned for an end to segregation in businesses in the south, they faced their own civil rights challenges. Housing discrimination and unequal employment were issues not only faced by African Americans living in densely populated northern cities such as Chicago, but also here in Newport.

Banner: Ermino Lisbon, Ernestine Lomax, and Elaine Parker picketing W.T. Grant Company store on Thames Street. 2018.015.216, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

[1] Thomas J. Sugrue and Haley Leuthart, “Northern Lights: The Black Freedom Struggle Outside the South,” (OAH Magazine of History 26, no. 1, 2012): 9–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23209967.

[2] Although sit-in demonstrations were becoming a nationally recognized tactic of civil disobedience by 1960, they began decades before. Although northern states prohibited racial discrimination de jure, Black citizens still remained “second-class citizens” through the practice of de facto segregation. Public accommodations such as restaurants informally maintained Jim Crow laws. As early as 1943, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized a nonviolent direct-action campaign at the lunch counter at Jack Spratt’s in Chicago. Founder of CORE James Farmer led a group of over two dozen in a peaceful sit-in demonstration, which resulted in policy change at the restaurant and all of the Black patrons being served. Other sit-in demonstrations occurred at a smaller and less publicized scale and were not a new concept.; Aarushi H Shah, “All of Africa Will Be Free Before We Can Get a Lousy Cup of Coffee: The Impact of the 1943 Lunch Counter Sit-Ins on the Civil Rights Movement,” The History Teacher 46, no. 1 (2012): 127–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43264079.

[3] Newport Daily News, Newport, Rhode Island, March 17, 1960.

[4] Newport Daily News, Newport, Rhode Island, March 29, 1960.

[5] Newport Daily News, Newport, Rhode Island, March 22, 1960.

[6] Newport Daily News, Newport, Rhode Island, March 29, 1960; City Directory of Newport, 1960.

[7] Newport Daily News, Newport, Rhode Island, March 22, 1960.

[8] Newport Daily News, March 29, 1960.

[9] Newport Daily News, Newport, Rhode Island, April 4, 1960.

[10] Ibid.

The post Solidarity with the South: Newport NAACP’s Boycotts in 1960 appeared first on Newport Historical Society.