Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, and I were on television this week. Well, one of us was, talking about the other two. But I should back up. When I started this blog in 2020, I noted the context and impact...

Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, and I were on television this week. Well, one of us was, talking about the other two. But I should back up.

When I started this blog in 2020, I noted the context and impact of the Taylor-Fillmore project’s beginning during a pandemic. American University’s campus was minimally staffed, everyone who could was working at home, and visits to archives and libraries were indefinitely postponed. I relied heavily on the generosity of archivists and librarians who located, scanned, and shared the manuscript letters in their care. When Associate Editor Amy Larrabee Cotz, undergraduate and graduate students, and other contributors joined the project, we interacted entirely via Zoom, email, and telephone.

A lot has changed. Americans still suffer from COVID-19, much as they still suffered from cholera after the pandemic’s height in 1848–49. But 2023 is not 2020. I want to update you on how we work now and on our first big in-person event.

In late 2021, we began returning to archives and libraries in person. As I wrote, we initially did so between COVID surges and under strict pandemic protocols. Things eventually got easier and more consistent. In 2022, research consultant David Gerleman and I hunted for Taylor and Fillmore letters in the Library of Congress and the National Archives amid relaxed capacity limits and appointment requirements. We appreciated both the opportunity to see the documents directly and to discuss sources with experts such as Michelle Krowl of the Library of Congress’s Manuscript Reading Room. Our database of letters from 1844–53 thus has grown rapidly. We now have more than 4,600. (Once we get to the presidential years of 1849–53, in about a year, that will double or treble.) Meanwhile, I had the pleasure of getting to know David Barker and Hannah Purkey, my colleagues at American University’s Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies, in person. As I’d expected, they are as kind and as committed to the project’s success in person as they had seemed from our respective remote bunkers.

The next steps after finding letters, as I’ve noted before, are choosing which to publish, transcribing those, and proofreading the transcriptions. Those tasks, which depend on digitized images and are often solitary, suit themselves well to remote collaborations. Little, therefore, has changed in how our editors and student contributors go about them.

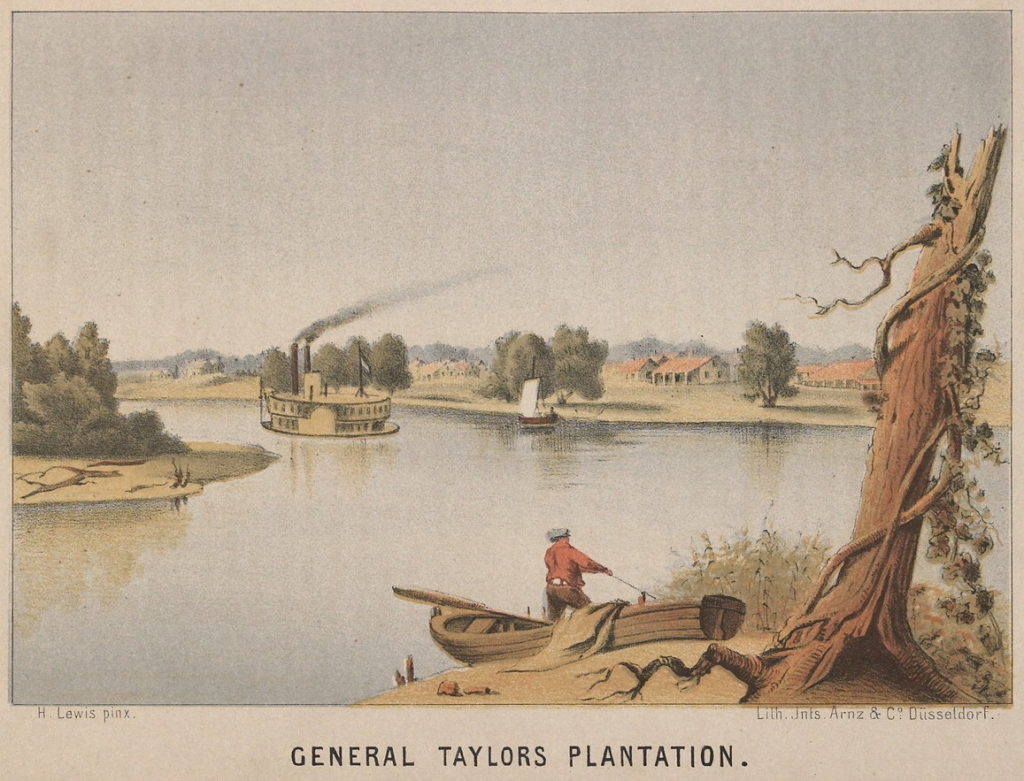

Then comes annotation. This year we reached the stage in editing our first volume—the pre-presidential one—when we write notes identifying the people, events, organizations, laws, and other topics that show up in the letters. The notes help make the letters not only available to readers in print and online but also accessible to those who aren’t familiar with everything happening in the 1840s (i.e., all of us). How we annotate is a large topic worthy of its own blog entry, so stay tuned. For now, I just want to point out how essential both remote and in-person resources are. The internet is vast, and we mine its seams—from Ancestry to fold3 to Google Books to FindaGrave to Chronicling America to the Handbook of Texas to other documentary editions like ours—for data on the famous and obscure people and topics featured in the letters. That was true before 2020, and during the pandemic some institutions (including the State University of New York, Oswego, home of the Millard Fillmore Papers) expanded their commitments to digitize historical data.

Yet, contrary to popular belief, not everything is online. We have actual books in our offices, and the libraries of American University and the Washington Research Library Consortium have far more. Still more books on paper and manuscripts on microfilm (including many held by the National Archives) are available to us via interlibrary loan. Our student editorial assistants, particularly Jamshid Mohammadi this semester and Nicholas Breslin last semester, have joined Ms. Larrabee Cotz and me in perusing those, um, ancient artifacts of print culture. Thanks to today’s relative safety of entering libraries, we thus can draw on all available sources to track down elusive references in the letters. In 2020 I thanked the workers in healthcare, education, and other essential industries who made remote work possible for some of us. Now I thank them and all others who have enabled a return to something closer to normal.

Speaking of normal, how about a conference? In 2020 our own staff didn’t meet in person, let alone invite a hundred others to come see us. I was involved with the Association for Documentary Editing (ADE), which each year since 1979 had held a meeting of people who produce editions of historical and literary documents. But even the ADE canceled its 2020 meeting and moved the next two to Zoom.

With the ADE hoping again to gather in person in 2023, it seemed the right time for a special location. So, we thought, why not the nation’s capital? Why not American University? Our staff volunteered to plan the conference, along with fellow Washington-area editors including those at the Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. On June 22–25, the Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies hosted over one hundred creators and users of documentary editions for a successful return-to-in-person conference. We streamed most of it, so several dozen more joined us on Zoom, a few even presenting remotely from around the country and the world.

Those of us on-site celebrated our return to conferencing with an opening reception at the Katzen Arts Center. That was sponsored by our Center, the University of Virginia Digital Publishing Cooperative (of which we’re a member), and the Primary Source Cooperative at the Massachusetts Historical Society. We thank them and the conference’s other sponsors: the University of Tennessee Press; the University of Virginia Press; the First Ladies Association for Research and Education (FLARE), based here at American; the National Humanities Alliance; the National Coalition for History; the Organization of American Historians; the Society for History in the Federal Government; and the Southern Historical Association. We also thank our colleagues at Katzen, the Washington College of Law, University Conference & Guest Services, and throughout American for their hard work to make the event happen.

Poster by University of Tennessee Press, a conference sponsor

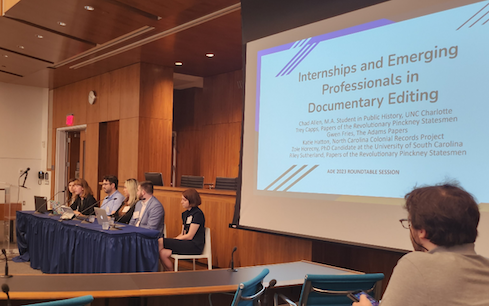

Four days of sessions covered the diverse work that documentary editors do. You can read the program here and watch recordings of several sessions here. Highlights—to pick a few out of many—included a roundtable of current and former student interns on editing projects, a FLARE-organized session on “The Documentary Legacies of First Ladies,” and a breakfast presentation by Mia Owens on the “History of Slavery and Its Legacies in Washington, DC.” Ms. Owens, now of the 1882 Foundation and the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, worked with the White House Historical Association as the inaugural fellow on that subject while she earned her public history degree at American. Between sessions, attendees enjoyed tours of the National Gallery of Art’s Archives, the Library of Congress’s Preservation Directorate, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, the Department of the Interior, and Eleanor Roosevelt–related sites around the city.

Session on internships in documentary editing

I mentioned TV, didn’t I? Well, we’re especially proud of two sessions. I joined editors from the Emma Goldman Papers, the Mary Baker Eddy Papers, and the Jane Addams Papers in a roundtable titled “Still Important Today: Recognizing Historical Patterns in the Present.” My colleagues discussed their efforts to engage audiences in learning about the present and the past. I talked about doing that through this very blog. Then we welcomed two very special guests: Shelly C. Lowe, Chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and Linh Anh Moreau, Coordinator of International Programs on the Memory of the World at UNESCO. These humanities leaders held a fascinating keynote conversation, facilitated by Christopher Brick of George Washington University, on “Public Humanities and Indigenous Voices.”

Those two sessions, especially the keynote, spoke to an audience well beyond the ADE and our university community. C-SPAN, wishing to share them with viewers across the country, recorded them and recently began showing them on its cable/satellite networks and its website. You can see the schedule of TV broadcasts or stream them online anytime here. Enjoy!

Beyond the practical benefits of in-person activities, for both our editorial progress and interproject collaboration, getting together helps remind us of the value of a professional community. I mentioned how nice it was, after the worst of the pandemic, finally to meet my colleagues at our research center face-to-face. At the conference, Amy Larrabee Cotz and I got to meet two of our student editorial assistants, Mercedes Atwater and Cameron Coyle. Both have contributed mightily to the Taylor-Fillmore project, and their hard work will be reflected in the volume of letters that we send off to the publisher a year from now. It was lovely finally to see them not on Zoom.

Editors Michael Cohen and Amy Larrabee Cotz with, in middle, student editorial assistant Cameron Coyle