This summer, a new national conversation emerged over the teaching of history. On July 19, the Florida Department of Education approved updated standards for social studies courses. These are the first in Florida to include a distinct curricular strand...

This summer, a new national conversation emerged over the teaching of history. On July 19, the Florida Department of Education approved updated standards for social studies courses. These are the first in Florida to include a distinct curricular strand on African American history. One requirement for middle school lessons attracted widespread attention: “Instruction includes how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Some politicians, teachers, and others criticized what they saw as a defense of slavery. Last week protesters marched to the school board’s headquarters in Miami in an attempt to prevent the standards’ implementation in Miami-Dade County. The political scientist William Allen and the documentary historian Frances Presley Rice, members of the task force that wrote the standards, defended them against the criticism. They wanted students “to learn how slaves took advantage of whatever circumstances they were in to benefit themselves and the community of African descendants.” Omitting this information, they feared, “reduce[s] slaves to just victims of oppression [and] fails to recognize their strength, courage and resiliency.”

The debate caught my eye in part because Dr. Allen and Dr. Rice invoked a family I had mentioned in this blog. They named sixteen examples of “slaves [who] developed highly specialized trades from which they benefitted,” including Lewis H. Latimer. That draftsman and inventor was never in fact enslaved. But his parents, Rebecca and George W. Latimer, were. As I noted in January, Millard Fillmore received a letter about their flight from Virginia enslavers in 1842. They settled in Massachusetts, where Lewis was born. It is not clear that the parents found a use in freedom for skills developed under slavery; George, assigned by his enslavers to drive a dray and to run a grocery store, found work as a paperhanger once free. But thinking about the educational controversy and this connection with our letters got me wondering how else the letters can shed light on the skills of enslaved people. That question led me away from Fillmore and toward Taylor.

Zachary Taylor grew up around the Black men, women, and children whom his parents enslaved at their plantation outside Louisville. As an adult, he inherited or purchased well over a hundred enslaved people. They served him in many capacities and locations. The writer Walt Bachman, in The Last White House Slaves, uncovers the stories of those forced to work as personal servants for him and his White family at frontier army posts. They included children whom Taylor fathered with a woman he enslaved. Later, Taylor brought enslaved people to Washington to work in the White House. He was the last president to do so.

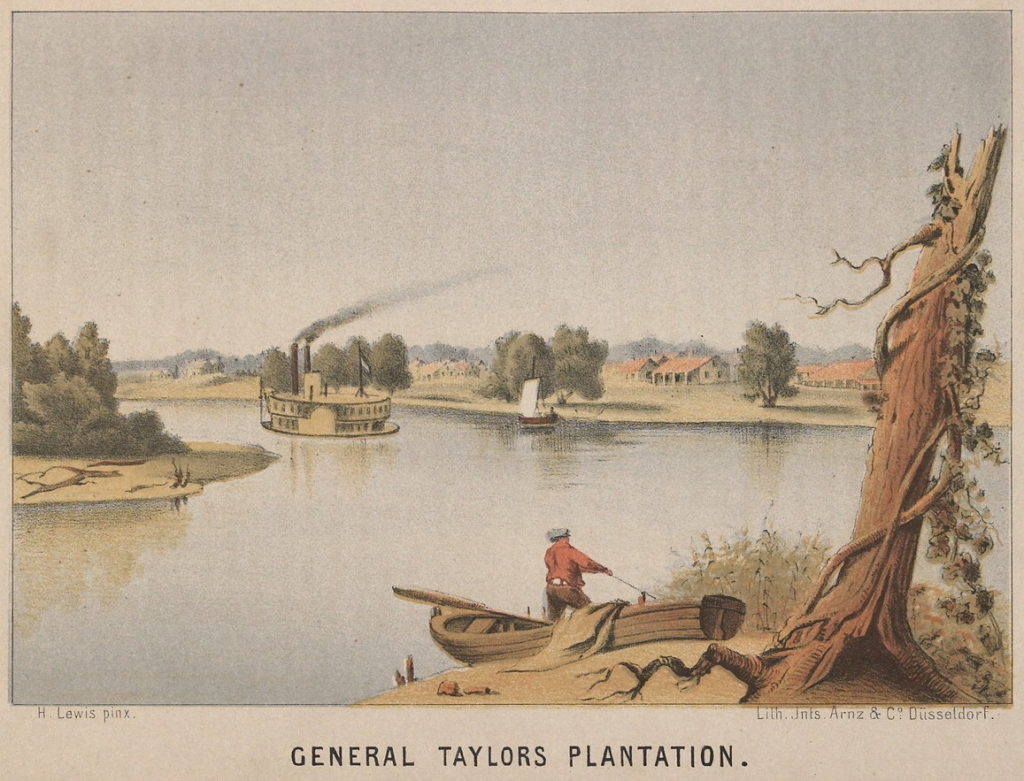

Henry Lewis, Das illustrirte Mississippithal [1857]. Library of Congress.

As in much of the antebellum Deep South, the chief product at Cypress Grove was cotton. Taylor often instructed Ringgold to have the enslaved people plant, harvest, gin, pack, and transport the cash crop. On June 18, 1845, he summed up his goal: “I have no fears if you have your health, & the servants keep pretty well . . . you will make fully as much cotton as you can secure, in a neat & proper manner.” Difficult work that drew on Eli Whitney’s recent invention of the cotton gin (which renewed cotton’s profitability and promoted the continuation of chattel slavery—another point made in the Florida standards), the forced cultivation of cotton created fortunes for many plantation owners.

Taylor also had the people at Cypress Grove grow other crops. In the same letter to Ringgold, he mentioned corn and “a small parcel of Muskeet grass seed” that he had ordered “sent to you, with directions how to propagate it, which I wish most carefully done.” Ringgold probably relayed the instructions, but enslaved people certainly did the “careful” job of growing grass to feed the livestock.

When discussing other agricultural tasks, particularly those involving timber, Taylor more explicitly recognized the skill of those whose labor he exploited. On December 16, 1845, he directed Ringgold to “select eight or ten good axmen, & keep them getting wood & tumber [i.e., timber or lumber], such as picketts, hogshead & barrel staves, or shingles after ascertaing which was the most profitable.” On February 23, 1846, he stressed the need to cover plantation expenses by selling wood. He directed Ringgold “to put six good axmen to cutting wood & keep them at it & hauling, until you want them for cotton picking.”

In referencing “good axmen,” Taylor acknowledged a skill that certain men at Cypress Grove had learned, presumably from each other. But only to the White overseer did he explicitly ascribe intelligence, telling Ringgold on September 15, 1845, “I feel easy . . . in confiding the management of my affairs to your good management-” Enslaved Black people, in his eyes, performed skilled manual labor. White managers determined what labor should be done, when, and how.

Enslaved people on James Hopkinson’s plantation, Edisto Island, SC, possibly in front of their house [1862]. Library of Congress.

Sometimes he gave them more than the basics. On June 18, 1845, he directed Ringgold to give ten dollars to enslaved people who had done extra work transporting cotton. That November 13 (as quoted in the Louisville Daily Courier, October 25, 1848), he had the overseer “DISTRIBUTE AMONG THE SERVANTS AT CHRISTMAS . . . FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS.” But Taylor granted them basic survival needs and occasional gifts within the context of their enslavement. Black people followed the directions of those who considered them property and received a minute portion of the wealth they created when the self-described owners chose to give it. Never were they given the option of leaving their enslavement to use their skills elsewhere.

As you’ve probably noticed, all the letters I’ve mentioned are by White men: Taylor’s surviving letters and Ringgold’s missing ones. None are by the enslaved Black people themselves. There’s a reason for that. Literacy was not among the skills that enslavers valued among Blacks. Many associated the ability to read and write (and particularly the ability to study the Bible) with the potential for rebellion. Colonial Georgia, in 1770, passed a law forbidding anyone to teach enslaved people to read or write. In the 1830s, motivated by antislavery rebellions led by literate Blacks, other states followed suit. Although Mississippi, the location of Taylor’s Cypress Grove, did not, enslavers there nonetheless discouraged Black literacy.

Yet some Americans forced into servitude did gain an education. Frederick Douglass began learning “the A, B, C” from one of his enslavers and continued studying after her husband ended the lessons. A British visitor to Cypress Grove in 1849 met a “very remarkably intelligent-looking youth” who “had taught himself to read and to write.” According to Taylor’s son, who had spied on the young man, he had “saved every candle-end he could find, and deprived himself of sleep night after night to accomplish his design.” Linking literacy with rebellion and invoking the name of a Haitian revolutionary, the Briton speculated that this man might “become a Toussaint l’Ouverture in time.” Some enslaved people even wrote letters. James K. Polk, Taylor’s presidential predecessor and a fellow Mississippi planter, received one shortly after his election from Long Harry, a blacksmith he enslaved. Likely dictating to an amanuensis, Harry reported on November 28, 1844, that he had campaigned for Polk, winning him “some votes,” and had won money and goods by betting on the White man’s election.

So, yes, Americans who were considered property and forced into lives of permanent servitude did develop skills. They learned and taught each other agricultural and mechanical skills that profited those claiming to own them and that preserved the institution that deprived them of freedom. But the lessons came about neither by the Black people’s choice nor for their benefit. Enslavers dictated them for their own purposes and rewarded them as they unilaterally deemed fit. (Refusal to perform the skills, as when a man repeatedly escaped from Polk’s plantation, was rewarded with an instruction to “beat him well.”)

Learning to read—or, for that matter, to escape—was, indeed, Black Americans’ choice. They did hope to benefit from those skills, whether as free men and women who could earn an independent living or as enslaved ones who could spread religion and perhaps start an uprising. Those chosen and potentially beneficial lessons, however, were not the purposes of slavery. They were its antithesis. Enslavers and lawmakers—even those, such as Taylor, who expressed a commitment to enslaved people’s health and contentment—had an interest in those people’s staying put and developing skills that cultivated cotton and timber, not ideas and rights.

Eventually, slavery ended. Most who lived under it never saw that happen. A few, including Douglass, successfully escaped. For the rest, it ended when Union troops went south and masses of Blacks joined their camps during the Civil War. Thereafter, within the strict limits of an incipient sharecropping economy, formerly enslaved Americans could use their abilities for purposes of their choosing. We know little, so far, of the postwar fate of those whom Taylor had enslaved. Matilda Graham died in Cincinnati in 1875 (Cincinnati Daily Times, June 22), and C. A. Combs died in St. Paul, MN, in 1896 (at the age of 112, according to the Ely Miner, April 22), but they left few records of their activities. Bachman, in The Last White House Slaves, concludes that Taylor’s theretofore enslaved son William H. Taylor was sent to Ontario, Canada, and became a farmer when his father became president.

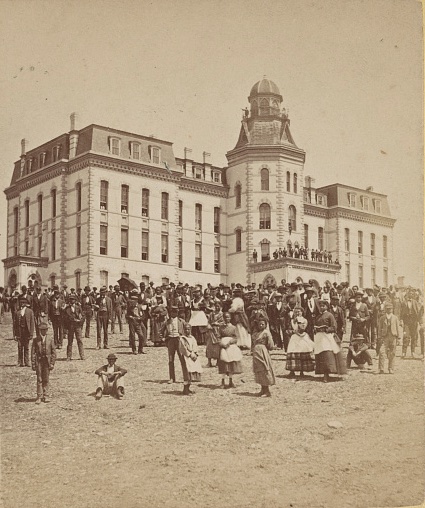

Beyond the Taylor communities, freedpeople could now potentially use their skills for “personal benefit.” But the emancipation that enabled this, like reading and fleeing during slavery, was antithetical to the system that had taught those skills. Besides, the vast numbers of formerly enslaved Americans who built and attended schools and colleges, so they could learn new skills, shows that they considered those acquired under slavery to be wholly inadequate. Slavery, unintentionally, had helped teach them the benefits of the skills they were denied.

Black students at Howard University [1867–1920], photograph by Joshua W. Moulton. Library of Congress.