The death of Tyre Nichols and the charges of murder against five Memphis police officers have reignited debates about policing in America. Amid other African Americans� deaths following actions by law enforcement, including those of Breonna Taylor and George...

The death of Tyre Nichols and the charges of murder against five Memphis police officers have reignited debates about policing in America. Amid other African Americans� deaths following actions by law enforcement, including those of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, this tragedy involving a Black victim and mostly Black officers again brings questions of race to the fore. Earlier in this blog I discussed Taylor�s and Fillmore�s roles in the history of racial oppression. They participated in the enslavement of Blacks and the violent expulsion of Native Americans from the East. But it is worth getting more specific. Both men made key decisions about the policing of People of Color.

Taylor�s relationships with Native Americans did not end with the US-Indian wars in which he commanded troops. Assigned to a succession of western army posts, he was responsible for keeping peace among the various Indian and White inhabitants on the frontier. Sometimes that meant contributing to major negotiations, as when, in 1829, he attended a council at Fort Crawford in what is now Wisconsin. It ended with Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Bodewadmi leaders� ceding eight million acres of their peoples� land to the United States.

More often, Taylor and his subordinates settled local disputes through diplomacy or military force. After overseeing the construction of Fort Scott in 1842, for example, he dealt with the conflicts that arose among Native peoples as Whites pushed them from their previously expansive separate territories into a confined space in today�s Kansas. In 1844, while commanding the Second Military Department, he resisted an effort by an Arkansas sheriff to arrest two Cherokee men for the 1839 murder of another. Despite a grand jury�s indictments, he told Adjutant General Roger Jones on February 14, he feared that pursuing the old case would �cause great excitement in the [Cherokee] nation.� Over the next three years, while in Texas and Mexico, Taylor occasionally received complaints from White residents about violence or theft by Native peoples. When able, he responded by trying to arrest the offenders. On July 25, 1844, for instance, he reported to Jones on an �expedition� he had sent against a �small party of Indians who committed an outrage.� His soldiers had destroyed a camp, but the targets had escaped. Taylor considered that result adequate. (Both letters are in the National Archives.)

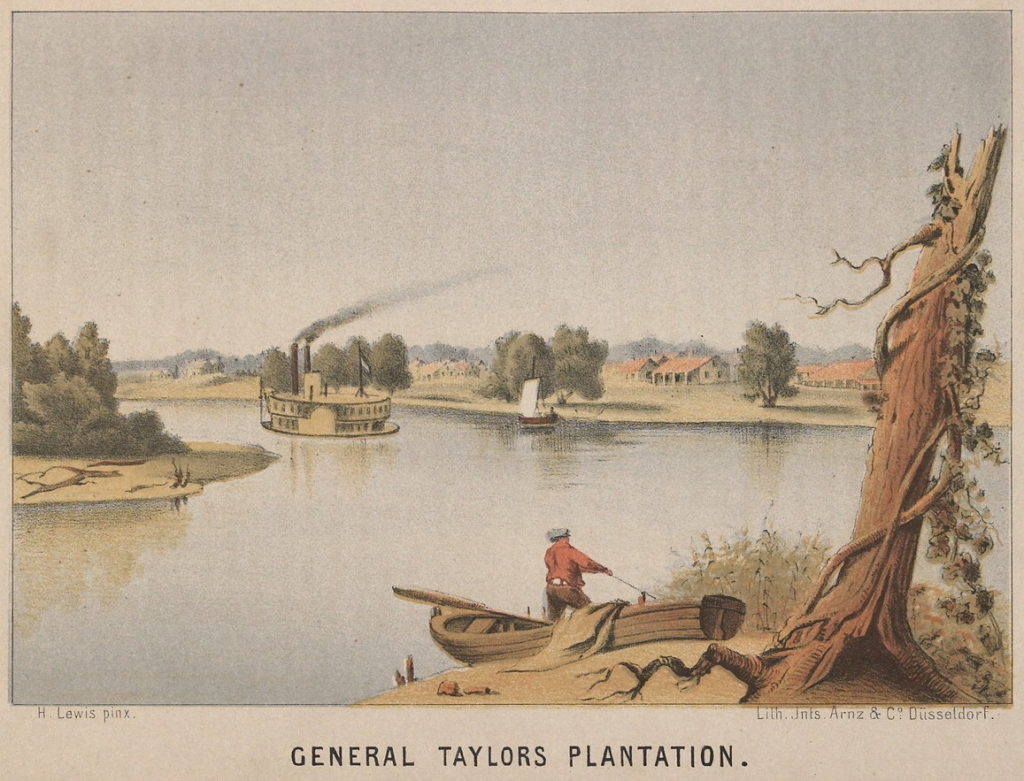

Back in the East, police efforts often targeted African Americans. The historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has argued that the United States� tradition of gun ownership rights developed from the perceived needs to expel (or exterminate) Natives and to enslave Blacks. Regardless of the causality, Whites expended much time, ink, and weaponry on Indian removal and the enforcement of slavery. Taylor regularly corresponded with Thomas W. Ringgold, whom he employed to oversee the people he enslaved on his Mississippi plantation. His instructions did not mention punishment. He noted what tasks the enslaved people should do and insisted that Ringgold �preserve . . . the health of every se[r]vant on the establishment.� But the overseer was there to force them to stay and work. He was successful, as no one is known to have escaped. Men and women did escape from the plantations of Taylor�s presidential predecessor, James K. Polk. Polk regularly paid Whites to capture and return them, and he instructed his overseer, on retrieving an escapee, to �beat him well.�

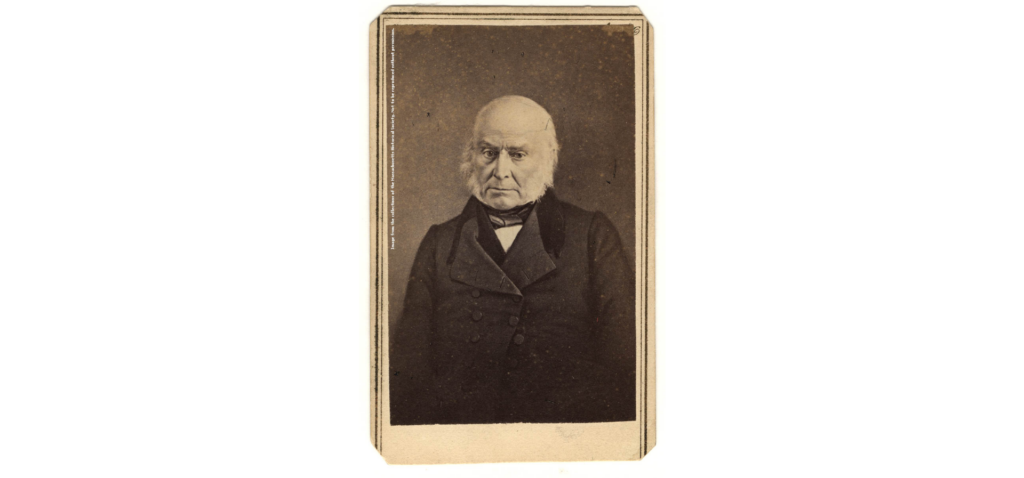

Curiously, Fillmore more explicitly involved himself in the policing of Black people than Taylor. The New Yorker who privately called slavery a �curse� (to Hiram Ketchum, May 9, 1848, SUNY�Oswego) built his career and his legacy in part on support for using force to control the lives of African Americans. Advocating a popular plan among Whites, known as �colonization,� he hoped that Blacks eventually would be freed from bondage and sent�voluntarily or forcibly, he did not say�to their �native Africa.� More immediately, he promoted the use of federal police forces and White civilians to return those who had escaped from servitude back to their enslavers.

The Constitution�s Fugitive Slave Clause, enacted in 1789 when the national charter took effect, required that enslaved people who escaped to other states be returned. Congressional legislation laid out the details. Enslavers, such as Polk, could pursue their human property or pay other private actors to do so. Federal, state, and local judges were responsible for certifying the escapees� capture and return. Of the thousands of people who fled slavery each year, a few attracted legal and popular scrutiny. Over time Fillmore played increasing roles in those debates.

George W. Latimer, lithograph by Thayer & Co. New York Public Library.

Friends of Fillmore wrote to him about one fugitive case while he was seeking the Whig vice-presidential nomination in 1844. In 1842 George W. and Rebecca Latimer, a husband and wife owned by different enslavers in Norfolk, Virginia, had fled together to Boston. James B. Gray, who owned George, pursued them and notified Boston authorities. George, though not Rebecca, was arrested and charged with larceny. Protests erupted across Massachusetts, and Black men surrounded the courthouse to prevent his return south. A legal battle ended with his release as a free man. Virginia�s governor nonetheless called on Massachusetts governor John Davis to return him to slavery. Davis�s refusal upset Southern Whites and hurt Davis�s prospects of being nominated as vice president. The Washington publishing firm Gales & Seaton, on May 1, 1844, advised Fillmore that this could work in his favor: not having taken a stance against the re-enslavement of escapees, he might be a more acceptable nominee to Southern Whigs (SUNY�Oswego). That hope did not pan out�neither Fillmore nor Davis got the nod�but the affair did influence Massachusetts politics. The state legislature passed the Latimer Law, which forbade state officers to aid the arrest or return of those claimed as fugitives from slavery.

Four years later, the fugitive slave question impacted Fillmore more significantly and prompted him to address it. Opponents of slavery, by then, were helping escapees to reach Canada and freedom through a network labeled the �Underground Railroad.� Soon after his nomination as vice president in June 1848, Fillmore�s critics accused him of having aided or at least �countinanced� that network. He responded with disgust. The charge that he had allowed Black people to become free, he told his friend Nathan K. Hall on June 15, was �infamous� and clearly false. �I should as soon think,� he wrote, �of denying the charge of robbing a hen roost.�

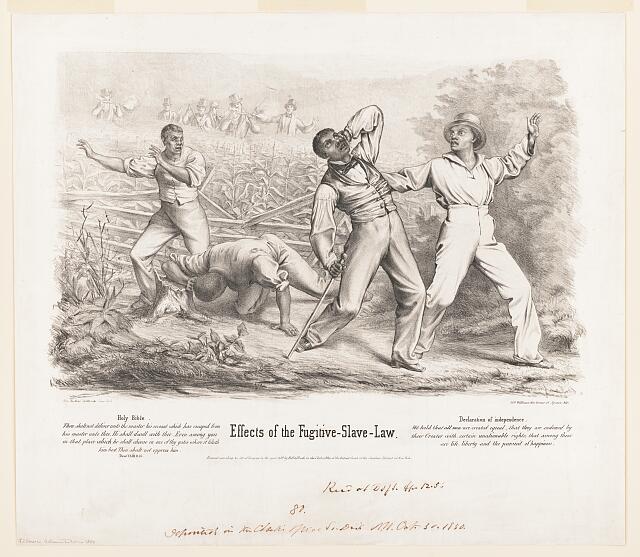

Once in the White House, Fillmore put his support (or at least acceptance) for re-enslaving escapees into practice. In 1850 Congress and the president�first Taylor and then, after his July death, Fillmore�were developing legislation to create state and territorial governments in the West. Most Southern politicians wanted slavery permitted there; most Northern ones wanted it banned. The final compromise made California a free state but allowed slavery in the territories of New Mexico and Utah. It also banned most slave trading in the District of Columbia. Finally, to gain Southern support, it included a new and stronger Fugitive Slave Act. The act assigned federal commissioners to enforce it and, most controversially, enabled them to force private bystanders to help arrest people suspected of having escaped from slavery. State provisions such as the Latimer Law, designed to shield both state officers and Black Americans from the enslavement process, were thus circumvented.

Armed posse pursuing Black men under the Fugitive Slave Act, lithograph by Hoff & Bloede, 1850. Library of Congress.

President Fillmore promoted the Fugitive Slave Act during the congressional debate. Some biographers have inferred his reluctance from his waiting two days before signing it; he signed the other compromise bills without delay. But his known writings (our project is always hunting for more) reveal few if any moral qualms. During the remainder of his presidency, he enforced the law and opposed its repeal. Late in his term, as a lame duck unconcerned with reelection prospects, he did pardon two White men convicted of aiding a large-scale escape from slavery years earlier. Some thought this showed another side of his mindset. But for the men and women who were returned�or, if falsely charged as fugitives, sent for the first time�to slavery, the Fugitive Slave Act was Fillmore�s most important legacy. It also contributed to the escalation of sectional political tensions that led to the Civil War. A police force of the United States, and even its private citizens, had been officially deployed to keep Black people in perpetual servitude.

The removal of Native Americans and the enslavement of Blacks were major uses of the US government�s police power before the Civil War. But the law enforcement choices by Taylor and Fillmore that I just narrated are vignettes in a complex and multifaceted history. Many now, after watching the news, want to learn about the goals and decisions that shaped the policing practices Americans variously depend on, admire, question, and fear today. Books by historians such as Laurence Armand French and Robert C. Wadman and William Thomas Allison trace that history, including its racial facets. Bryan Vila and Cynthia Morris edited a collection of historical documents on The Role of Police in American Society; as a fellow editor, I particularly invite readers to explore those primary sources. For a quick introduction, though, one might begin with another blog. Ten years ago Gary Potter, at East Kentucky University, wrote a handy six-part �History of Policing in the United States.� It covers the story succinctly but far more broadly that I can do here.