first the quaLity Of yoUr music tHen its quAntity and vaRiety make it Resemble a rIver in delta liStening to it we becOme oceaN —John Cage: “Many Happy Returns” for Lou Harrison Even though he spent most of...

first the quaLityOf

yoUr music

tHen

its quAntity

and vaRiety

make it Resemble

a rIver in delta

liStening to it

we becOme

oceaN

—John Cage: “Many Happy Returns” for Lou Harrison

Even though he spent most of his career in California, Lou Harrison forged a lifelong relationship with his native Oregon. Born in Portland in 1917, he lived here until the family moved to California when he was 10.

This weekend — appropriately during Pride Week, as he was early on one of America’s out-est and proudest gay composers and worked for equal rights — Portland State University celebrates Harrison’s centennial in two concerts, a musical salon and academic symposium. The following tales of the composer's long relationship with Portland come from our book, Lou Harrison: American Musical Maverick:

***

|

| “Buster” Harrison, ready to steal the show in a 1920 Portland production of Daddy-Long-Legs. |

The exotic decor sprang from the ambitions of his mother. Born in Seattle in 1890, Calline Silver grew up in the Alaskan frontier with her sister, Lounette. Despite these rough circumstances, their father saw to it that both girls had music lessons, at a time when music was an important marker of good breeding and refinement for young women. After her father died and Cal raised herself from this rustic beginning to a middle-class ideal, she became a woman of strong will and determination, qualities that her son would inherit. She married affable, fair-skinned Clarence Harrison, a first-generation American born in 1882, whose Norwegian father had, like many immigrants, changed his surname from exotic (de Nësja) to blend-in conventional: Harrison.

Like many upwardly mobile West Coasters, Cal Harrison was attracted to the allure of Asia and regarded exotic artifacts as exemplars of refined taste. Such decorations were common in Portland homes since the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair. Japan alone spent a million dollars on its exhibit, which featured exotic (to American eyes) arts and crafts, sparking a local infatuation with Asian art and culture. Many middle- and upper-class houses boasted “Oriental Rooms” festooned with Asian and Middle Eastern furniture and art, “Turkish corners,” and other symbols of what many Americans still regarded as the mysterious East.

That Pacific exoticism also manifested in music. When Lou was born on May 14, 1917, Hawaiian music was the most popular genre in America. Radio broadcasts of Hawaiian slide guitars and the clacks of his mother’s mah-jongg tiles supplied the soundtrack to some of his earliest memories—and inspired one of his last compositions eight decades later.

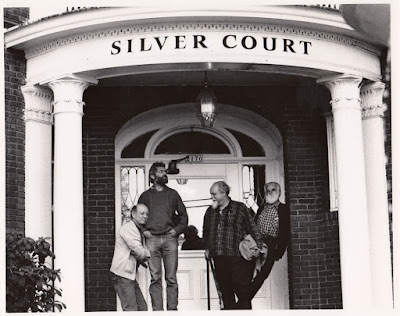

The Silver Court’s surrounding Irvington neighborhood in northeast Portland had been developed as an exclusive enclave only twenty years before Lou was born. Connected to downtown Portland’s cultural riches by trolley, the “streetcar park” originally catered to the toffs (including lumber barons). During Lou’s childhood, however, the changing neighborhood’s new Queen Anne revival, Craftsman, and Prairie School-style homes welcomed more middle-class people like the Harrisons. They had built the handsome Silver Court Apartments (which still stand at 22nd and Hancock streets) shortly after Lou’s birth, when Calline received a substantial inheritance from her family in Ohio, who owned a manufacturing business; her grandfather’s widow’s death in 1910 led to a partition of the estate, and the Harrisons used their share to build the three-story, thirty-unit apartment building. The money allowed them to hire a family to take care of the apartments, including their own.

|

| Harrison visiting Silver Court Apartments in 1987: (l to r) Bob Hughes, Charles Shere, Harrison, Bill Colvig |

Clarence and Calline did share a love of cars—she was reputedly the first woman to drive across Portland’s Steel Bridge—and the family enjoyed then-common Sunday drives and picnics in the country. They appreciated the scenic beauty—waterfalls, the spectacular Columbia River Gorge, Mt. Hood (which dominated the eastern skyline), and nearby Mt. Tabor—and gave Harrison and his brother, Bill (born three years later), a lasting love of the outdoors. Harrison never met his grandparents and had little contact with extended family during childhood, so his parents exerted the greatest family influence on their eldest son. Their two most persistent legacies were his lifelong loves: arts and reading. Aunt Lounette played violin, often accompanied by Calline on the piano, and little “Buster” Harrison would dance.

He took the stage early. Calline worked in a Portland beauty shop, and one of her regular customers, Verna Felton, ran a small theater company that in 1920 was producing Jean Webster’s 1912 play Daddy-Long-Legs. They needed a young boy for a silent walk-on role as a little orphan, and Calline volunteered two-year-old Buster, who, encouraged by candy, improvised his lines—for the irrepressible little Lou, it turned out not to be a silent role after all—and won the audience’s heart, getting his picture in the daily Oregonian newspaper and an invitation to reprise the role on a Northwest tour and in another production in Washington. The experience gave Harrison both a taste for performance and a deep set of separation anxieties that never left him.

Harrison’s Oregon upbringing left lasting impressions on the budding young musician: an inclination toward the outdoors and nature’s beauty, an affection for high-culture art and music, and a performer’s sense of the stage and the audience. Although his family moved to California when he was nine, Portland would always be a special place for him. After beginning his music career in San Francisco, Los Angeles (briefly) and New York, Harrison returned to Portland during the summer of 1949 and 1950 to compose for and accompany dance performances of his music at Reed College. There, he met Remy Charlip, a young dancer (in the company of their mutual friend Merce Cunningham, among others) and theater designer who became his lover.

Much later, toward the end of one of the richest lives ever lived in American arts, the then-octogenarian Harrison came to realize that in pursuing, studying, and ultimately creating original music deeply informed by the traditional sounds of Asia, he was “trying to recapture the lost treasures of my youth.”

“I was surrounded by a household of very fine Asian art,” he said, “and as I grew up, I wanted to reproduce that. My problem and my drama has been, could I recover the lost treasures of childhood? Well, I discovered that if I couldn’t make enough money to buy them, at least I could make some.”

Throughout his eventful career, Harrison would pursue the magic first experienced amid the Asian art treasures gracing his childhood home in Portland’s Silver Court apartments. He’d find it in mysterious shops in San Francisco’s Chinatown, in Korean temples and Indonesian percussion orchestras, Medieval musical modes, ancient Greek tunings, in new instruments contrived from junkyard detritus. From these unlikely ingredients, he would fashion beguiling new sounds far removed from the conventional music of his time and place. Like his mother, he would embrace beautiful strangeness — and make it feel like home.

***

On June 16-17, Portland State University hosts CeLOUbration, which brings together Venerable Showers of Beauty gamelan ensemble, Portland Percussion Group, PSU faculty and student performers (including FearNoMusic co-founder Joel Bluestone, guitarist Bryan Johanson, pianist Susan Chan, violinist Tomas Kotik and more), and other Portland musicians (singer Hannah Penn, cellist Diane Chaplin, percussionist Florian Conzetti, pianist Adrienne Varner, and more). The two concerts feature music by Harrison from the 1930s-1990s and new music by Cascadia Composers Bonnie Miksch, Susan Alexjander, Greg Steinke, Lisa Ann Marsh, and Matthew Andrews, written in the Harrison tradition.

Friday’s concert showcases some of the pioneering percussion music Harrison and his musical partner John Cage wrote and performed in San Francisco in the late 1930s and early ’40, plus chamber music. Saturday’s show presents music for guitar, chamber music, and some of Harrison’s music for the melodic Javanese percussion orchestra called gamelan, with soloists on Western instruments like trumpet, saxophone, and voice.

Concert tickets are available online. The festival also includes a free salon and symposium, a screening of Eva Soltes’s 2014 film Lou Harrison: A World of Music, and talks and presentations about Harrison’s life and music. Copies of Lou Harrison: American Musical Maverick and Venerable Showers of Beauty’s new CD containing previously unrecorded Harrison music for gamelan will be available for purchase.

©2017 Bill Alves & Brett Campbell. Book excerpt used by permission of Indiana University Press. A shorter version of this story appeared in The Oregonian/O Live. If you enjoyed reading about Harrison’s music, there’s a lot more where that came from. Our new biography of Lou Harrison is now available from Indiana University Press and elsewhere.