Following the success of their directorial debut, Loving Vincent, co-directors and life partners Hugh and DK Welchman knew they would continue making movies with oil paintings. However, they didn’t want to simply do another exercise in bringing an artist’s...

Following the success of their directorial debut, Loving Vincent, co-directors and life partners Hugh and DK Welchman knew they would continue making movies with oil paintings. However, they didn’t want to simply do another exercise in bringing an artist’s paintings to life. They wanted to try something new, which led DK to suggesting they adapt The Peasants, the Nobel Prize-winning novel by W?adys?aw Reymont and a cornerstone piece of literature from her childhood growing up in Poland. As soon as Hugh read his own copy, he was floored by it. “The way Reymont writes is very poetic and very colorful,” he explains to Skwigly. “It doesn’t feel like a landscape that could exist in reality.”

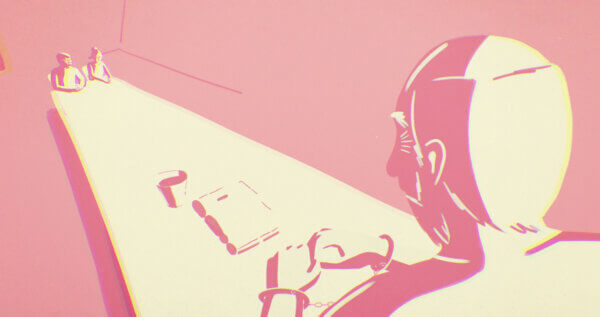

Despite four years and an arduous production process, the final product perfectly embodies Reymont’s imaginative style through deeply expressionist filmmaking. Unlike Loving Vincent, which was filmed largely using static shots set against green screens, The Peasants introduces a more limber camera, capturing dance and fight choreography within makeshift cardboard sets and even exteriors. “It was clear that to get the emotions in this village, where it can be quite claustrophobic with intense emotions, we wanted the camera to stay very close to the characters,” Welchman says. They wound up doing so many involved camera maneuvers that “the camera [became] a character in the film.” The final result is one of the year’s most spectacularly animated films and one of the medium’s crowning achievements.

On the cusp of its UK release, Hugh Welchman sat down with Skwigly to discuss the film’s development, lead star Kamila Urzedowska, and the future of oil painting animation. Here is our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

When you think about Loving Vincent, it’s a very conventional conceit for a lot of people. “We’re going to tell a story about Vincent van Gogh and we’re going to tell it in the style of his art and his world.” The Peasants is really expanding the boundaries of what we can do with this medium because it’s suggesting that we can take this beloved novel that has already been adapted into live action once and give it this hand-painted animated treatment. When you’re thinking about this medium, what are the kinds of stories that, when you hear about them, you think painting is the way they should be told?

That’s a very interesting question, because you can do anything in oil painting animation. It’s a form that has been developed over 500 years, so more than photography, more than film, more than anything. It can really convey reality in a new, infinitely nuanced way. Taking something as simple as, say, the dance between Antek and Jagna. The way that the painters are using the light, the way they’re simplifying the movement of her hair and her dress, can all contribute to the emotional impact on the audience. You’re applying creative application for five hours on a sixth of a second of animation. It’s all of that thinking going into that one second, so it does have infinite possibilities. On the other side, it’s incredibly labor intensive. You have to be sure that you can contribute something extra by doing it in oil painting animation compared to doing it in, say, live-action or in CG animation. For Loving Vincent, we had a very special reason. Afterwards, we really wanted to show that painting animation didn’t just have to be used to bring a painter’s works to life. It can be used in other ways.

The way [The Peasants’ original author W?adys?aw] Reymont writes is very poetic and very colorful. It doesn’t feel like a landscape that could exist in reality. If you go to the village of Lipce where, as a young man, he worked as a railway signalman – the characters come from his two years of living there – it looks nothing like the book in terms of these incredible, beautiful descriptions of nature and the changing of the seasons. That’s why it was very appropriate to retell it as an oil painting animation. He’s a Young Poland movement novelist and we bring his work to life inspired by young Poland movement painters. The other reason is that when any of us think about 19th century peasants, there’s probably a Millet painting coming into our head if we’re from North America or Western Europe, or [if we’re from] Britain maybe some pre-Raphaelite paintings we saw in Tate Britain when they went on the school trip. We don’t really have famous images of peasants in the 19th century in terms of photographs or films. We think of peasants as paintings anyway, so it’s only right that a film about peasants is painted.

Where does the decision come in to incorporate the moving camera more? In Loving Vincent, you filmed a number of performances and those were put on backgrounds, but The Peasants incorporates the camera in a much more traditional live-action context.

It came from DK [Welchman, co-director and co-writer] and it also came from the cinematographer, Radek [Ladczuk], during the first couple of weeks on set. It was always our intention that there wouldn’t be too much camera movement because, on Loving Vincent, it cost us four times as much to do moving camera shots. I think DK just instinctively rebelled. She wanted to be able to move the camera as a director. In discussions with Radek, it was clear that to get the emotions in this village, where it can be quite claustrophobic with intense emotions, we wanted the camera to stay very close to the characters. Once we choreographed the dance and you saw how beautiful it was, we wanted to be close to Jagna and Antek when they were dancing together and we wanted to see the expressions on their faces, in which case you need Steadicam. We had those experiences in the first couple of weeks and by then it was really established that the camera was a character in the film. It was allowing us to tell the story better, so then we just had to learn how to paint the moving camera.

The central performance from Kamila Urzedowska as Yagna is such a revelation. Not only is she an immensely talented performer but her face is so gorgeously rendered in this medium. When you’re auditioning, are you considering an actor’s face and how it might appear in oil painting? Is that something you saw in Kamila when you were first working with her?

Well, it was clear that the camera loved Kamila. She’s pretty beautiful in the flesh but she’s stunning when photographed and I think we made her even more stunning by making her into a moving painting. With Kamila, we chose someone who was unknown. All the other actors are very famous actors in Poland, but we felt, for Jagna, we needed a fresh face, someone that was new to the audience. We didn’t actually do painting tests of her, but we knew that she was going to transfer into painting beautifully. What we weren’t expecting was that we’d have a semi-mutiny from the painters at the beginning. None of the painters wanted to paint her. [laughs] Her features are so symmetrical and flawless that if you make even a slight error with the brush strokes, she doesn’t look right. They were all like, “we want to do the older women” or “we want to do the male characters” because they’re more forgiving in terms of oil painting. We basically forced our best painters to do it, but then, over time, everyone had to paint Yagna, because she’s in most of the shots. They were using paint brushes with single hairs for her eyes and eyelashes. People really fell in love with her. It was very emotional when we took her to the Serbian studio and the painters met her for the first time. They had been painting her for a year and a half and then they got to meet her in the flesh and it was quite moving for them.

I know you have a third film planned to make a pseudo-trilogy of oil painted films, but even beyond that, what is the future of this medium? It’s obviously very labor intensive, but I think that there is an audience for it. As one of the few people who are spearheading the mainstream use of this medium in feature filmmaking, what is necessary in order for this medium to prosper?

Ultimately, I think a studio has to come along and go “we want to do this as a big budget animated film.” Loving Vincent made money, it proved itself at a certain level. The Peasants doesn’t have the advantage of Van Gogh, but on the other hand, in Poland, it’s the most Polish successful film for the last four years. No other Polish film since COVID has broken one million admissions and we’re currently on 1.6 million admissions. The crazy thing is that the box office actually grew from its second to third week compared to the first week. I think people thought “oh, period drama based on a Nobel prize winning novel, probably a bit boring,” but then word of mouth was like, “okay, this is a super intense, passionate, and really action packed film.” With Loving Vincent, fans often went to see the film more than once. In Poland, we’ve had that same thing with The Peasants. We’ve had people posting that they’ve seen it three or four times. If we can get that kind of audience in other countries as well, then I think there’s a future for this. We have our trajectory, as filmmakers, with what we want to do with this kind of filmmaking, but for it to not be just a footnote in cinema history and for it to grow beyond me and DK, I think a studio has to go, “oh, we want to do something in this style,” and I think that will only happen if The Peasants does as well or better than Loving Vincent. We’re really in the hands of the audience. We don’t have the kind of advertising budgets of studio films or anything like that, so it’s really about the audience discovering it and supporting it and going to see it.

It’s as much in the studio’s hands as it is in the audience’s hands, as is usually the case.

Absolutely, absolutely.

Hugh, we look forward to the next hand-painted effort. Thank you for all your contributions to this medium. All animation fans are in your debt.

Thank you very much for saying so.

The Peasants is now playing in UK cinemas.

The post The Peasants | Interview with Co-Director Hugh Welchman appeared first on Skwigly Animation Magazine.