By Hugh David. Tatsumi is a self-acknowledged country bumpkin who is nonetheless a well-trained fighter. He and two companions leave their remote village to head to the Imperial City to find a way to relieve their friends and family...

By Hugh David.

Tatsumi is a self-acknowledged country bumpkin who is nonetheless a well-trained fighter. He and two companions leave their remote village to head to the Imperial City to find a way to relieve their friends and family from ruinous taxation imposed by the authorities. Yet the Imperial City is filled with unimaginable amounts of corruption and evil from supernatural sources. Tatsumi is immediately swindled after reaching the City and nearly loses everything, but finds himself allied with an unlikely group of assassins.

With other titles following in its wake such as Moriarty the Patriot, Akame ga Kill’s approach to the morality of traditional post-Star Wars fantasy/SF narratives stands out as a turning point in how modern shonen titles address the ideological stances of heroes and villains. In doing so, it asks questions fans have often asked of other franchises over the years, only this time without offering the obvious answers. But do the harem trappings and gore-tastic fight scenes dilute this approach?

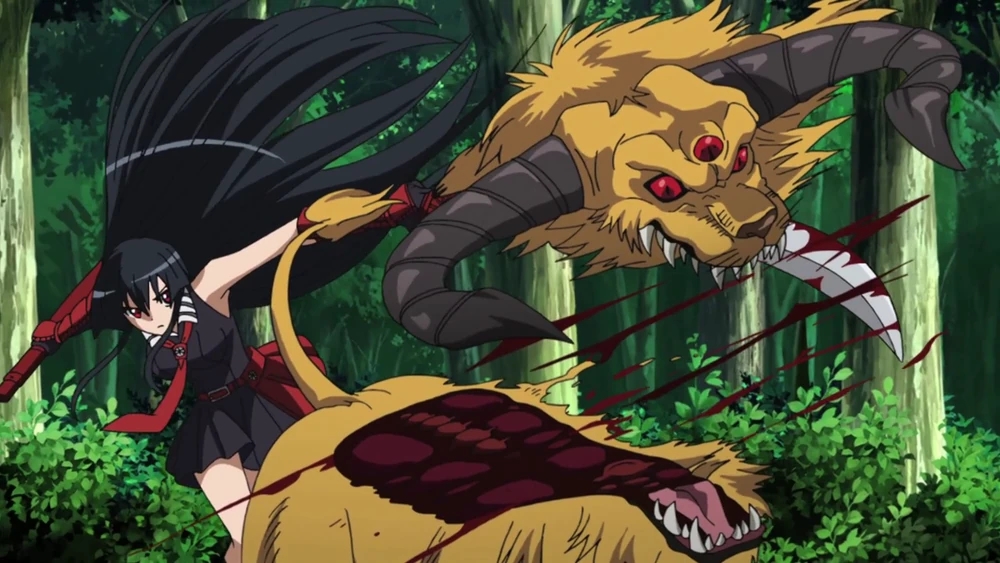

The opening episodes, in which the hero Tatsumi tries, D’Artagnan-like, to join the Imperial Guard, but is refused due to budget cuts, then gets all his cash stolen by a pretty lion/girl and is taken in by a rich girl and her family, rattle through cliches and tropes at light speed, albeit gradually undercutting them. However, subtlety is not Akame Ga Kill’s strong suit, and the rich family are revealed to enjoy capturing and torturing rural fortune-seekers like Tatsumi, while the lioness turns out to be part of the Night Raid assassins, a special brigade within the Rebel Army tasked with selected kills in the ongoing war between the Imperials and Rebels. Tatsumi, in this to save his village (he made his cash monster-hunting), is given that most honourable motivation, at the heart of the majority of East Asian action cinema and storytelling: vengeance for his dead childhood friends, who are amongst the victims of this first wealthy family. Joining up with the rebels, the scene seems set for a fairly standard narrative.

For all the talk of ‘the people’ vs. the Child Empress and her corrupt First Minister, the story is quick to complicate the audience’s feelings for both sides of the conflict. While only one side is seen to commit torture, qualities like loyalty, family and vengeance are still emphasised across the Imperial Guards we meet, and especially the formation of their own specialised brigades to counteract the Night Raid. Meanwhile, the latter try to avoid innocent bystanders, but are quick to justify the wiping out of whole families and their servants for the actions of their elders. Lines are drawn then blurred, then lost behind the harem-esque comedy and occasional erotic silliness. Any pretence at seriously addressing the initial political stances seem to fade slowly.

However, the show avoids simply becoming a revolting series of horrific injuries and spurting blood through two choices: one narrative, one visual. Very quickly, seemingly major characters start dying off, often in drawn-out near-Shakespearean ways. By the halfway mark of the series both brigades have to bring in new characters with new fighting abilities to replace the losses. Those deaths, however, are not trivialised; both sides find themselves often regretting their life choices in their final moments, or believing their cruel actions justify their death at the hands of their enemy. They often mourn those they leave behind, or lament what they are now cut off from achieving. In the case of the members of the Night Raid, we are often treated to final POV shots from their eyes as they close them for the last time, set to their final words on the soundtrack. This sense of placing us directly in the final moments of lead characters is something rarely seen in any medium, usually done only for visual effect, not for the emotional one. It changes how the audience perceive everyone, raising the stakes of our investment in the Night Raid while having us truly consider the choices made and costs accrued on both sides of such a militarised political conflict.

In the end, while many have written off the show as simply revolting, the true revolutionary aspect lies not in the lip service paid to revolutionary politics, but instead in the humanising of all on both sides of the conflict, however horrific and inhuman their actions may be. It acknowledges an important truth in any conflict, that death is both all creatures’ inescapable fate, and also the great social equaliser. Revolutions come and go, but what really matters are the lives touched and saved along the way.

Akame ga Kill is released by Anime Limited.