While fans tend to think about production circumstances as black and white, Frieren exemplifies what success tends to look like in the real world: a result of resourceful management, delegation of the right tasks to the right people, and...

While fans tend to think about production circumstances as black and white, Frieren exemplifies what success tends to look like in the real world: a result of resourceful management, delegation of the right tasks to the right people, and ingenuous solutions to tricky situations.

It’s not a secret that the internet hates nuance as much as it loves false dichotomies. Recent events have been brewing a myopic discourse around anime production, where the two popular titles of the moment must necessarily represent opposite ends of a black-and-white situation; if Jujutsu Kaisen S2 is such a poorly planned project, then Frieren must be in a thoroughly blessed situation, hence why its adaptation is so beautiful. We’ve written at length about the dangers of making such assumptions about perceived quality and labor conditions as a viewer, and even the fact that corporations exploit that opacity to whitewash their dubious management, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that neither case is so absolute.

Even though the schedule was never favorable in the least, JJK2’s team has still put together some stunning, fully realized work—especially in its first arc. And despite that being the norm for all of Frieren thus far, assuming that this is directly a consequence of having ample time and a comfortable environment at their disposal is a mistake. People should be more careful about suddenly painting studio Madhouse as a healthy workplace simply because they want to contrast that with MAPPA, because we’re still talking about the same company that just a few years ago kicked off the trend of being sued for egregious treatment of their management staff.

Extrapolating the reality for the studio as a whole from their treatment of Yuichiro Fukushi’s production line is also a misstep, as their status as the studio’s stars earns them an entirely different level of resources and staff availability. Even if we look within that one crew, the situation can fluctuate quite a lot; for some recent examples involving many people currently working on Frieren, look no further than the deep troubles their production assistant expressed when managing their episode of Spy x Family S1, or how exhausted a bunch of them were after the late move from Sonny Boy to Takt Op Destiny. By assuming that their success is a given due to positive circumstances, you’re not only turning a blind eye to their occasionally severe struggles, but also can entirely miss how that success happened.

This is all quite relevant to Frieren, as many of its triumphs are instead a showcase of savviness and efficient technique. In our first piece covering the series, we already went through the genesis of the project—and for as impressive as it is to convince TOHO producers that they want to turn your work into an anime after a single chapter, that was still in 2020, so much time had to pass to accumulate enough material to seriously approach the idea. The time constraints that surround this project on many levels are hardly an industry secret; even though Saito was obviously entrusted with the series before the broadcast of Bocchi the Rock one year ago, he was still quite busy with that up to the end of its run, which conditioned the progress for Frieren.

In the official starting guide for the anime, his interview alongside character designer Reiko Nagasawa and series composer Tomohiro Suzuki indirectly gave some hints about how tight its pre-production process was. Nagasawa explained that she based her designs on the then-current state of the manga, as styles tend to change notably during the early points of serializations before stabilizing. She specifically singled out up to volume 7 of the manga, which is to say, a spring 2022 release for this early stage of the design process where she had to decide on the style to follow. Having personally seen different types of design materials—color scripts, artboards, and the likes—being given the final OK between the fall and winter of that year, that about tracks to a production process that did start in 2022, but has only kicked out in full as the series director himself became free from previous obligations. And for a very ambitious 2 cours anime, that means they’ve had no time to spare.

What has made it so different from other titles in similarly tight situations, then? A variety of reasons, including the exceptionally high floor when it comes to technique. Frieren has the magnetism of not just a beloved young director who just put out a megahit, but two star animation producers. Everyone on the outside is giving credit to Fukushi, while often forgetting that Takashi Nakame is using his theatrical experience and ampler freedom as the second in command to cherrypick star guests that would normally never be available to TV anime; not exactly a hyperbole, as he’s responsible for the presence of Ghibli-aligned animators who hadn’t stepped on TV for multiple decades. And it’s not just those who make a difference: given that tremendous pull, this team has been able to be picky with all participants, which is exactly the opposite of the industry trend to hire the first person you see out of sheer desperation. Be it reliable veterans or youngsters who’ve proven that they can navigate the often obtuse production process, you can save so much time and trouble simply by building a team that will minimize the constant corrections to people’s work.

If you add that general aptitude to minute, but still very impactful specific moves, you can produce a series that punches way above its weight; one obvious example that I keep returning to is the pre-scoring, which they did apply across the entirety of the special 4 episode introduction to give it a special feel, and is now being tactically deployed to much success. Without entirely changing the normal workflow, a team this resourceful can still send individual animators a recording of the track planned for that particular scene. This often results in sequences that don’t just capture the feelings implied by the storyboard and script, but can match the intended tone on a whole different level through that synchronicity with the audio. Knowing when to pull off this stunt, and who to entrust these moments to, are also part of Frieren’s specific recipe for success.

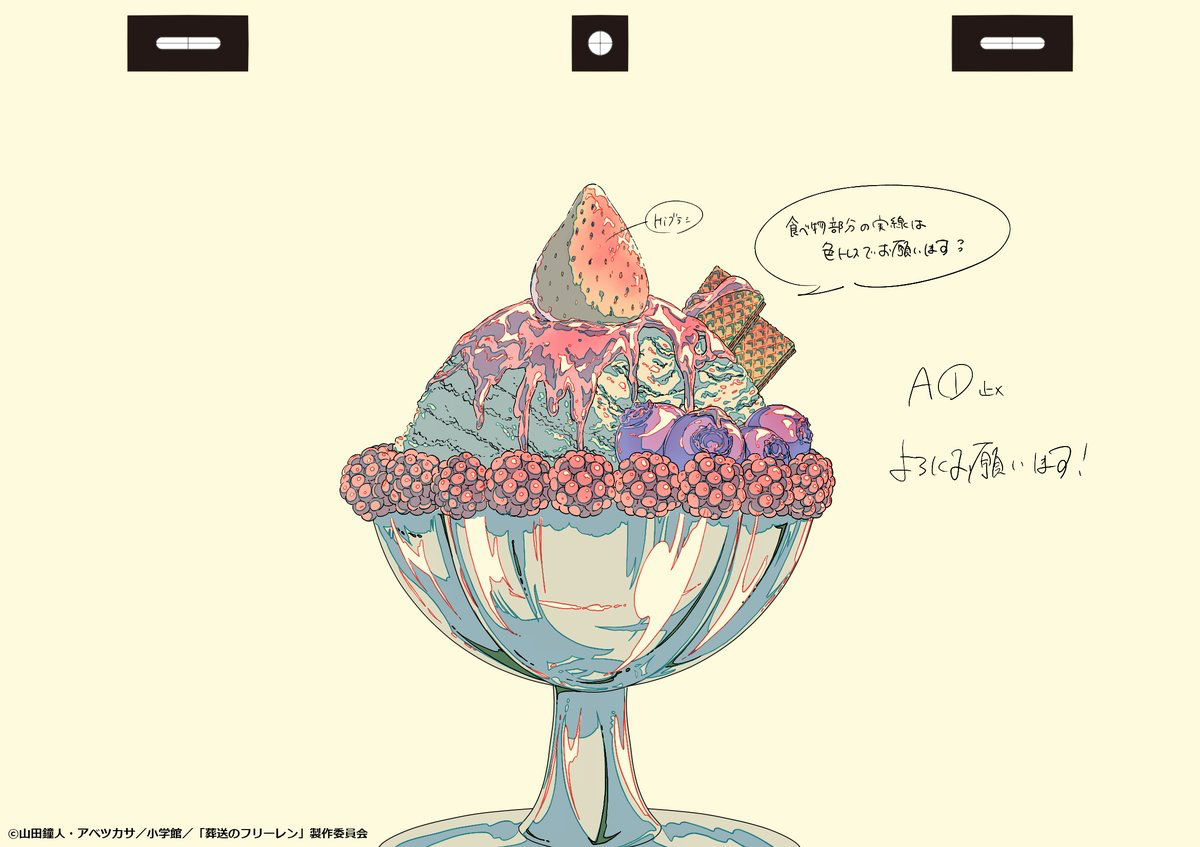

And that brings us back to Saito specifically, because one of his greatest feats in this project has been the delegation of tasks. As someone who was very busy in the early stages of the production, he simply had to find reliable members in the team to set the foundations for the adaptation he’d envisioned. As we also discussed in the first Frieren article, one of the most significant cases of this is Seiko Yoshioka, whose various credits as a concept artist and the likes fall short of explaining her massive role in the worldbuilding process. Due to that packed schedule and his struggle to convey everything verbally, Saito exposed the cornerstones of his vision and gave her room to imagine Frieren’s entire world and societies far beyond the confines of the original manga, tying it all together with their relationship to the passage of time. Be it the color scripts to set specific moods, extensive design work to solidify the customs of the people in Frieren’s world, or the many season/age variants for all she paints to underline that overarching theme, the presence of people like Yoshioka made the job easier for everyone else—from a director who could sigh in relief, to all the staff members who came later and were presented with clear, tangible goals.

The shield location of Qual was depicted with the image of villagers creating a barrier-like seal with stones and dedicating it. Relief carvings of goddess worship are engraved at the base of the stones.

The picture is used with permission from Madhouse.

#frieren #????? pic.twitter.com/Gdvw2xgik1

— YOSHIOKA SEIKO (@seiko11) October 20, 2023

Another aspect where Saito has successfully entrusted responsibilities to his comrades, one that has been quite relevant across these recent episodes, has been the action. We noted that Fukushi had actually pitched multiple projects to him beforehand, but that Saito rejected them because he felt they were too bombastic and not really up to his taste. The truth is that, in that same Nikkei Entertainment interview, Saito went further and said that action simply wasn’t his thing. As far as he’s concerned, it’s simply something he’s not good at. Had it not been for the reputation of Fukushi’s team and the knowledge that he’d have certain individuals around him, perhaps this Frieren pitch could have met a similar end as those discarded titles.

Mind you, Saito’s inability to handle action is a relative, self-inflicted judgment. If you look at his career, one of the most pivotal points was Monster Hunter Stories: Ride On, the long-running series where he had his storyboarding and directing debut, as well as a place of very meaningful meetings for him. Daiki Harashina, who’d graduated from the same university as Saito a few years earlier, went through the same experience across that project—and ever since then, they’ve been inseparable, which of course does include Shinashina having a major role in Frieren too. The ace animator in that production was Toshiyuki Sato, whom we still see as a very important ally for Saito now that he has leveled up to series direction duties. Friendship truly is forever.

Contrary to what you’d assume from Saito’s words, though unsurprisingly if you’re acquainted with this franchise, we’re talking about someone who first stood out within an adventure series where one of the main draws is the action component. Given the preferences of many of his friends, Saito has often found himself working in action anime, where he has shown he can get the job done just fine. Great, even! It’s also undeniable, though, that he has always gravitated in a different direction than those bombastic pals; he would for example favor effects-heavy scenes where he could exploit his abstraction abilities, call dibs on acting sequences, or simply be entrusted with the more contemplative moments that balance out the hectic work of his peers. Given those preferences, and the fact that the representatives of the original work told him to not hesitate to put together an action spectacle when necessary, Saito had to choose the right people for the job. And as we saw across the most recent arcs, that he did.

Speaking of which: everyone who works with Hiroki Uchiyama calls him a genius, so perhaps they’re onto something.

If we return to the point where we left the series last time, we’re met with a nice summary of the themes that episodes #01-04 beautifully encapsulated. Frieren constantly deals with the passage of time, mixing its inescapable, objective effects with the even more significant subjective effects. We’ve seen the physical aging of this world and its characters, as experienced by an elf who in theory operates on an entirely different scale. And yet, it’s clear to everyone but her that the supposedly insignificant 10 year trip with her old party was a life-changing experience, because the weight of personal relationships can go way beyond the exact amount of time people have spent together.

We saw a nice embodiment of that conclusion in Fern’s trial to become a fully-fledged mage, and we see it once again with Stark. The first time we meet him, he’s surrounded by children of the village he has come to treasure, and behind him is a suspiciously missing chunk of a mountain. Though the formal reveal only happens later, Frieren herself quickly grasps that these are the results of his harsh training to protect the villagers—again, a very significant physical dent on stone so sturdy that time itself would take an eternity to impact it so strongly. As we briefly pointed out already, the following episode extends those same ideas to Stark’s scars, as similarly physical marks of love. And why go this far? In his case, it may be for the smile on some kids’ faces, and in Frieren’s, of her own party as she learns some goofy magic; again, this adaptation gains a lot with the much more diverse, whimsical portrayal of magic compared to the original manga. A purely objective view of time could never explain their actions, nor would they make sense if you rationally tried to weigh those relationships. That is the irrational, beautiful humanity Frieren wants to depict.

While all of that is par for the course, a warrior joining the party had to be celebrated with some action spectacle for a change: and that is the signal for action director Toru Iwazawa to take the stage. While he has earned a reputation as an action specialist alongside comrades like Kai Shibata, Iwazawa barely has any experience leading episodes as an episode director and storyboarder. If there was one place where he’d be entrusted with that responsibility, it would have to be within this Fukushi production line, where he had recently made this debut in such positions—which as it turns out, do fit him quite well.

Iwazawa’s storyboard builds up to Stark’s confrontation with the dragon that has threatened the village quite effectively. On an emotional level, the match cut between his trembling hands and his master’s tells us that he has inherited not just his technique, but also the philosophy to embrace fear as a necessary aspect when facing a battle. His weighty walk builds up the tension, and Iwazawa’s boards do a great job of establishing the objective scale of the battle… just to progressively betray it as it explodes into a spectacular setpiece that goes far beyond that physical reality. The likes of Keiichiro Watanabe, Shingo Yamashita, Yen BM, Tatsuya Yoshihara, Definitely Not Yutaka Nakamura, and Hironori Tanaka were gathered not just by the very capable management team we’ve been talking about, but also by Iwazawa himself. No one better than a genuine action expert to know the type of sequence that will satiate his peers’ desire to go all-out.

While that rightfully earned a lot of attention, I’d be betraying myself if I didn’t shout out the rest of the episode. For starters, Iwazawa’s boards are quite nice even beyond the action itself; I particularly enjoyed how they first highlight the barriers between Fern and Stark, just to put them on the same page with a simple turn of perspective—simple and effective! While it has no action, the second half of the episode is dominated by another very eye-catching artist in animation director Akiko Takase, credited under her pen name of Takasemaru.

It wasn’t that long ago that there were genuine fears that she would quit animation altogether, as she was part of Kyoto Animation during the arson attack that shook her to the core, but we’re slowly seeing her return to very specific projects. On the one hand, she has been providing all sorts of illustrations for KyoAni projects again, and as Takasemaru, she’s gradually accepting more standard animation tasks. Standard in nature anyway, because as usual, her presence as supervisor changes the relationship between detail and ease of animation that everyone thinks of as normal. It’s easy to notice how the level of intricacy skyrockets with her corrections, but more importantly, she manages to marry that with her old studio’s careful acting principles; it’s no coincidence that there’s an attention to complex fabric and how personal mannerisms affect it right as she takes over as the supervisor, making it feel straight out of Violet Evergarden. Anime is simply a better place with her around to match ideas that normally seem at odds. Why not have smoothly acted, supremely detailed artwork sometimes?

After a thematically cohesive, but mostly episodic affair for the first 6 episodes, #07-10 are the first genuine arc in the series. That begs for a bit of a change in our approach, and not just because the structure demands you look at the whole rather than individual episodes. For all the praise I’ve personally given to this early material, I don’t find this first encounter with demons to be as thematically sound. Even if you ignore the racial trappings of the genre, Frieren at this point hasn’t quite figured out how it wants to portray demons; Frieren’s harsh prejudice is objectively correct according to the narrative, but there is friction with a characterization that in the end hints at some affective links existing between them that are perhaps not so unlike human bonds. Although I don’t think the anime has fully solved this issue, I do find it interesting how they’ve emphasized the malice in the titular elf at points, and not just to showcase badassery; if demons are beasts, then perhaps so is Frieren, who is consistently framed closer to them than to humans, as a larger, scarier being. Even her smirk is just like Aura’s!

Add to that the less graceful pacing, and I admit that I don’t find it as tight as the preceding material. Again, hardly something I’d blame this team for: they were told not to touch the dialogue as much as possible, making it harder to compress the manga’s content, and so they had to commit to perhaps one episode too many—such is the reality of TV anime, where the decision is often between 24 more minutes or 0. While its ideas might not click in the same way and at points I’ve been hoping for the arc to wrap up already, at its best, the sheer enjoyment and appreciation of the craft I’ve gotten out of these episodes are undeniable. So, again, how has this production pulled it off?

The arc starts with another showcase of that power of friendship that rules the industry as much as it does the cartoons themselves. The storyboard is split between Naoto Uchida, whom you’ll always find near Saito, and another comrade in Keisuke “Desuran” Kojima. More interestingly, it’s actually outsourced to the latter’s new studio, following the friendly game of ping pong that these teams have been playing with each other for years. Though I say new, it has actually spun off his previous crew studio at Revoroot, having reformed around the idea of an efficient animation workflow using Clip Studio. Combine those ideas with Saito’s familiarity with Desuran’s work, and you have a high-quality outsourced episode that genuinely offloaded a lot of work from the main team; something you can’t take for granted nowadays, as subcontracted episodes can drain so much energy to correct shoddy or misguided work.

The following episode is another solid showcase by Tomoya Kitagawa, who has quietly been the best helper Saito could hope for. He was actually the first person other than him to draw storyboards for the series, which according to the series director himself was quite the challenge—after all, at that point you don’t have a model to follow, so he had to imagine what Saito’s vision exactly entailed. And after grasping that, he was entrusted with none other than the title drop moment, something that appears to be fated to happen in the eighth episode of a Saito series.

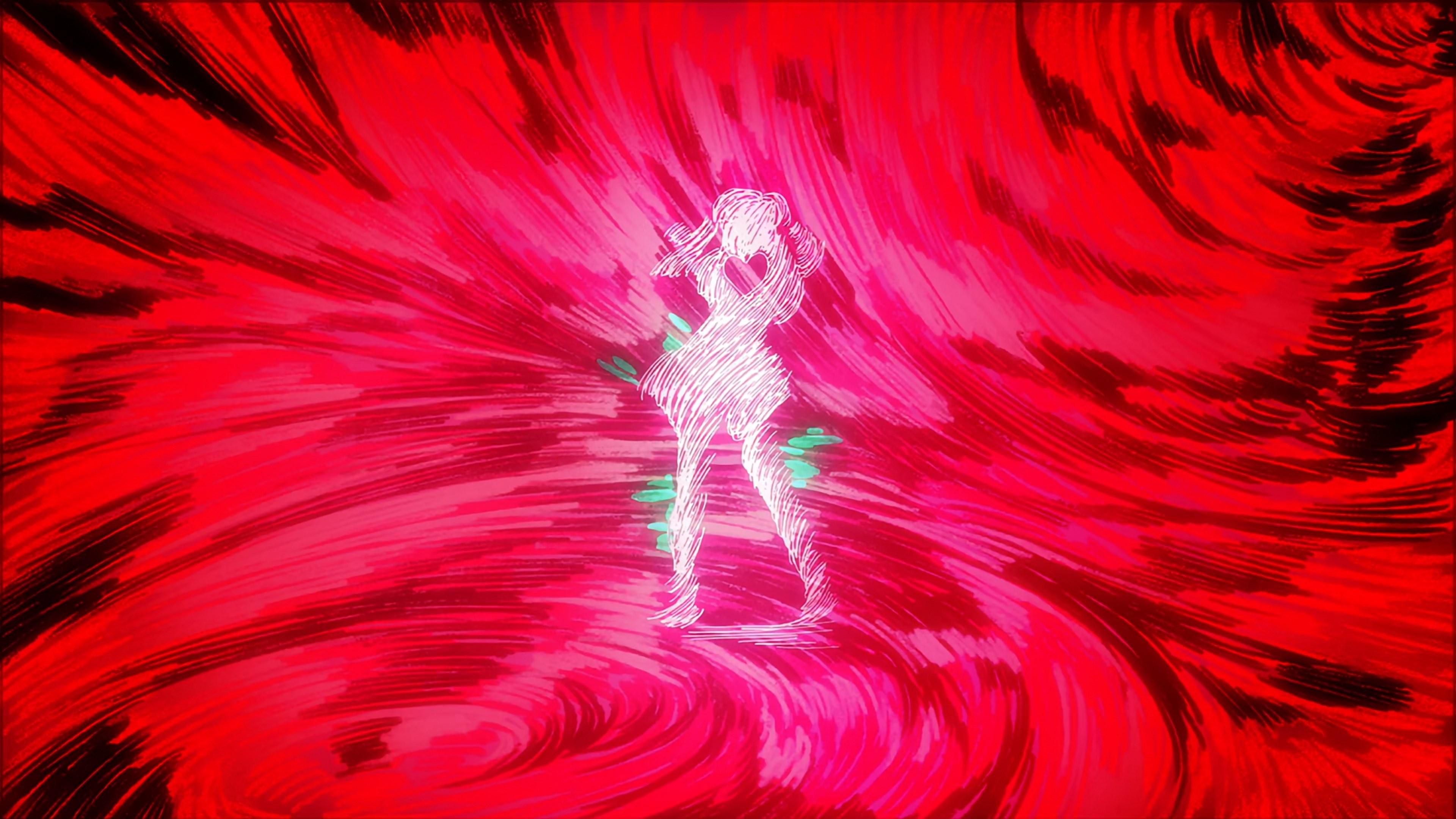

If you ask right about anyone, though, they will tell you that the highlight of this arc was episode #09: directed and storyboarded by Kouki Fujimoto, who can wear his first episode ever as a genuine badge of honor. To say that he was active despite all the new responsibilities would be to undersell his role; he contributed a whole lot of animation to the episode himself, both in terms of action and in the buildup that already raised the gravitas a great deal, while also leading the effort in unusual aspects like the actual lip-synching. It’s clear that over the last few years, Fujimoto has absorbed ideas and specific how-tos when it comes to crafting three-dimensional environments for action, and then combined those with the rawer appeal of his own linework. If you add to that some stunning moments of sheer cel power, you have an episode that feels like it’s perfectly balancing modern techniques with a more traditional appeal.

The action he conceptualized stands out by feeling grand in its individual confrontations—especially the two mages firing beams around—but also deeply connected and attentive. Cutting from one explosion in one fight to fluttering hair in another one that is happening in the vicinity, or using lighting effects visible across them both, makes them feel constantly connected; a cool feeling, and also one that prepares you for one distraction elsewhere determining the fate of the remaining fight. That attentiveness can go from all the information packed in mere loops of hair to genuinely contributing to the character writing. Fern’s expressiveness is quite the challenge, as just like Frieren herself she’s often deadpan on the surface, so a successful adaptation needs these elegant ways to solidify her character without spelling out too much, not even visually. By seeing her normal walk and even some hesitation, attached to one of the many moments when she has expressed her feelings of inferiority, her confidence and outright swagger in this fight hits even harder. If Frieren believes in her casting speed, so will she. And she will do so while matching the confidence of her arrogant foe.

After such a grand episode, how do you make viewers remain engaged in a much more restrained showing? That’s the dilemma that animation producer Nakame brought up himself, while noting that #10 had quite literally half the drawings than its predecessor. Saito’s answer to this problem was to entrust the job to Nobuhide Kariya, who already proved to grasp his vision perfectly in Bocchi the Rock; incidentally, that one was his debut as well, meaning that we’re seeing here one spectacular debut followed by a second time showing that lives up to it. It’s almost like these talented youngsters can live up to their potential in the right scenario.

Back in Bocchi, Kariya emphasized the visual diversity following Saito’s encouragement of experimentation. Not only was his episode a constant relay of different styles, but he also contributed the idea behind the famous zoetrope of anxiety a few weeks later, thus standing out even by that show’s quirky standards. Frieren aims for a more cohesive flavor, so Kariya instead focuses on capturing emotional and physical distance, with compositions that are quite good at implying something is there even if it cannot be seen yet. With that, the episode obviously builds up to the reveal of the hidden mana, an amusing Dragon Ball-like twist for a series like this.

Though I don’t think it was necessary to dedicate a full episode building up to that, I can’t fault Kariya’s crafty storyboarding in the least; who doesn’t enjoy using physically uneven standings to depict a scene that talks about societal standings among demons being determined by their unequal powerlevels, one of the more interesting ideas in this arc. The moments of tranquility after her master’s death are also some of the most gorgeous snapshots of Frieren’s life, but at the same time the saddest too. She’s left alone for generations, told not to stand out, so there’s a coldness even to the sunlight of those memories—one that takes the hero’s warmth to dissipate, as he can naturally tell there is more to Frieren than her cold surface. Saito has described Frieren not as a series about her discovering human feelings, but rather finding out that she always had them. That is why his opening sequence ends with the parties of past and present aligning, and why it was also important to nail how she was numbed to her own feelings. For an arc I don’t quite love, that’s one resonant ending.

Did you know that during the corresponding animation meeting, Kariya acted out Aura’s final moments with an umbrella, providing excellent references for her pained expression? Now you can join me in demanding that they make that footage public.

So in the end, what has been Frieren‘s trick so far? It’s impossible to reduce it to one simple recipe you could apply elsewhere, but I do believe that resourcefulness sums up the general idea. Saito is already a brilliant director, not just in what he has personally done, but also in the steps he has known to take back—and the people he has made way for with those. Though this production benefits from its high-profile nature, which gives it access to some resources most titles could never dream of, it’s simply wrong to assume that’s all there is to its success. We’re an industry where similarly large efforts crash constantly, largely because of external circumstances, but also because they haven’t figured out the type of ingenious solutions that have become the norm with Frieren. When talking about the latest episode, Nakame himself said it was quite troublesome to put together—after all, they’ve all been troublesome in their own way. From Saito’s packed schedule to Kariya falling quite ill during the making of this last episode, this team has had to worm their way out of many tricky situations. Moving forward, chances are that it’ll only get more difficult. But you know what? These people are damn resourceful, so I trust them.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, Sakuga Video on Youtube, as well as this Sakuga Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!