Hayao Miyazaki’s storytelling is built upon the dreamlike, empowering physics of the animation that builds his worlds. This offers a fascinating contrast with his latest film The Boy and the Heron, one noticeably burdened with weights—physical, psychological, of life,...

Hayao Miyazaki’s storytelling is built upon the dreamlike, empowering physics of the animation that builds his worlds. This offers a fascinating contrast with his latest film The Boy and the Heron, one noticeably burdened with weights—physical, psychological, of life, and of Ghibli’s legacy.

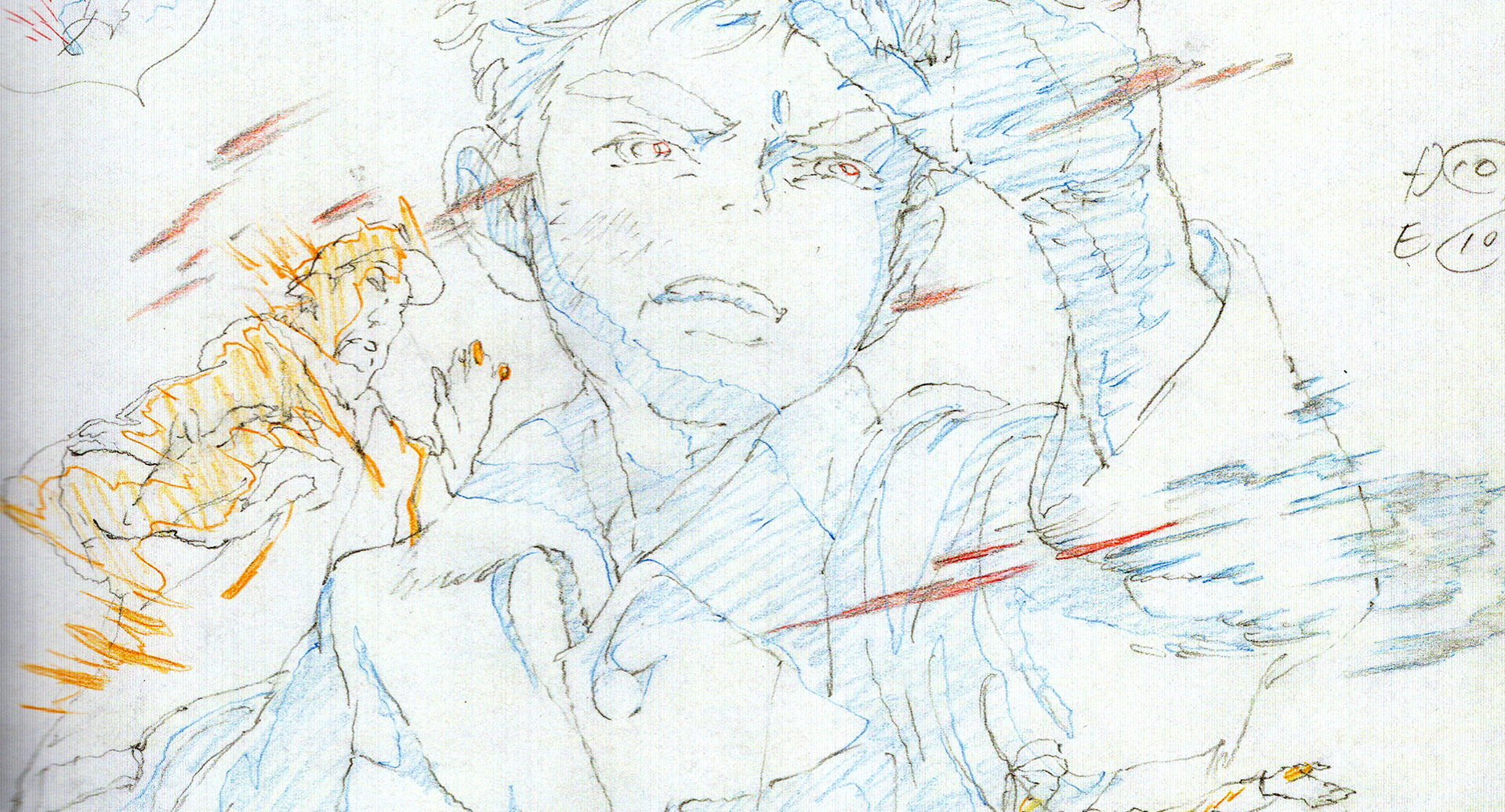

The first scene in The Boy and the Heron culminates in a bewitching, haunting fire animated by Shinya Ohira. His pencil, more adept than anyone else’s at twisting reality into an expressionist dreamscape, captures the blurry, chaotic experience of a child losing his mother amidst World War II bombings—making this one of many autobiographical aspects for director Hayao Miyazaki, as some of his first memories are that of the war. If the scene feels like it’s tailor-made for Ohira’s talents, it’s because it quite literally is. In this interview for Full Frontal, veteran star Toshiyuki Inoue mentions in passing that Miyazaki already had him in mind when drawing the storyboards; and indeed, according to Ohira himself in The Art of The Boy and the Heron, he was the very first key animator in the early meetings, besides a certain supervisor.

Ohira has worked in Miyazaki films before, and while the result is always excellent, it always felt like he had to leave the texture of his pencils at the door. His work in Spirited Away remains a personal favorite, as it appropriately feels like Chihiro has stepped into an entirely different world. The looser forms that make up Kamaji the first time we see him evoke his animalistic traits, putting us in the shoes of a child who would be torn between such a scary sight and the knowledge that he might still be her savior. For as much as it feels like a special scene, though, it doesn’t come across as materially different from the rest of the film. The same can be said about his collaborations with Miyazaki earlier in his career, like for Porco Rosso, as well as more recent ones like The Wind Rises; his iconic representation of this trance-like state is stunning, a fundamental building block for the character, but one that still feels like it uses Miyazaki’s ingredients even if the recipe is Ohira’s own.

That much is not true for this latest film, which is built to exploit the material idiosyncrasy of Ohira’s animation. The Boy and the Heron is not a movie about overcoming trauma, at least not as a singular focal point, but it still follows protagonist Mahito as he begins to move on from his late mother’s passing. Early on, we see him haunted multiple times by nightmares of that fire, always depicted by Ohira’s surreal, eerie animation. As he passes the literal torch to other animators, to other scenarios within a world of fantasy, fire becomes a much more colorful weapon in the hands of the likes of Yoshimichi Kameda. Ultimately, it sheds away any remaining fear factor to become a fun means of travel, joyously animated by the great Akihiko Yamashita. All of this, as it’s wielded by his late mother’s younger self, in a mission to rescue his new mom and accept her as such. That entire character arc hinges on an initial depiction of fire only one person could achieve.

In conclusion, that entire introduction is fantastic, and it’s not the first scene that took over my brain when watching the movie.

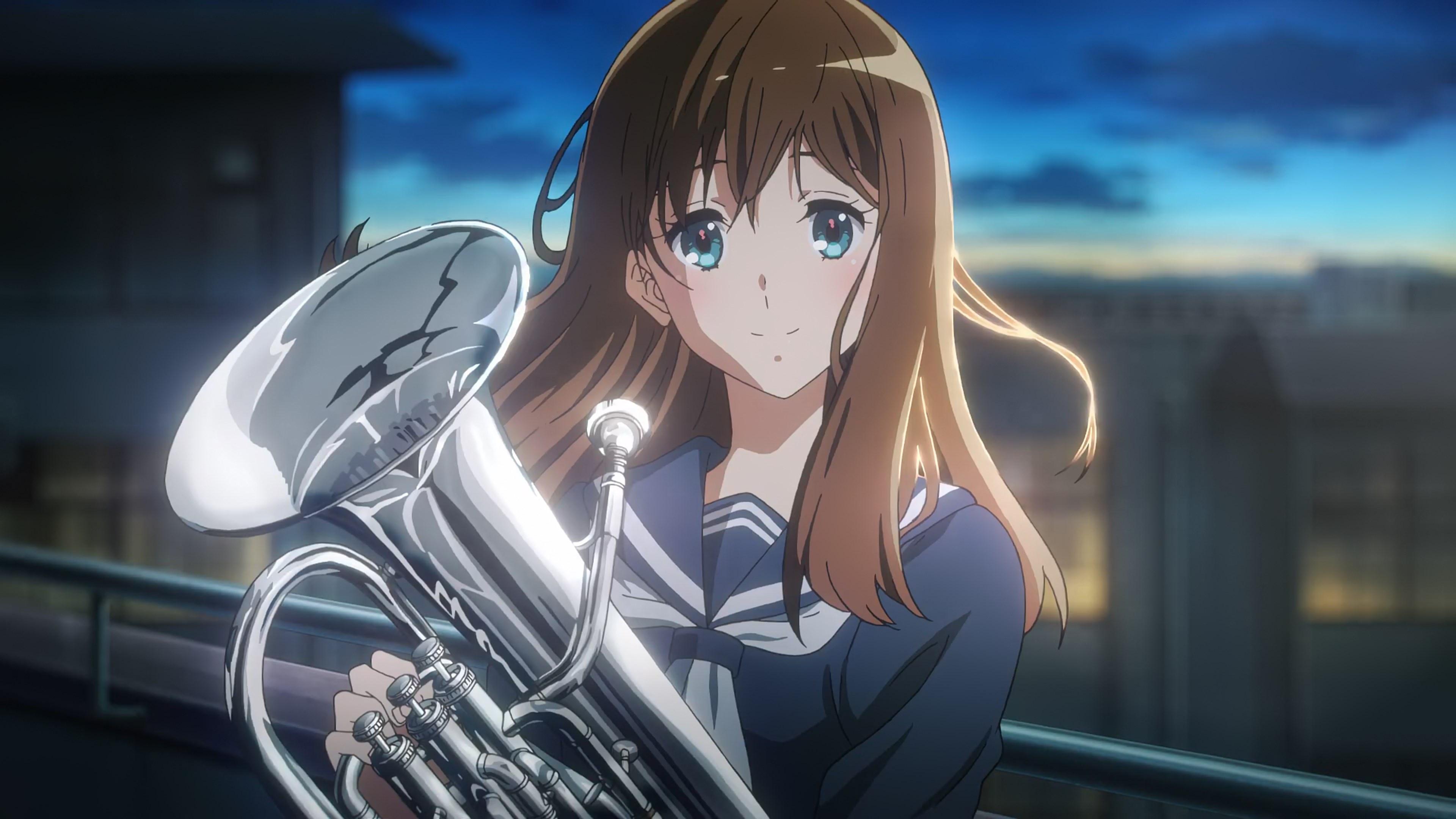

Instead, it was a scene soon after Ohira’s nightmarish spectacle that resonated with me, despite being unassuming on the surface. After that traumatic introduction, we see Mahito as he moves to meet the person who’s going to be his new mother—none other than his late mother’s sister, which gives a delicious ripple of complications to these relationships. Although it’s not spelled out, the movie reads as if she belongs to a noble family, whereas Mahito’s father feels nouveau riche, having hit his personal jackpot in the arms industry during the war. Again, we have a mix of Miyazaki’s personal experiences as that tracks to his own father’s career, with his broader knowledge of that era too; he pointed out to the team that such marriages were common at the time, and that less obvious anecdotes like Mahito’s dad frivolously donating money to the school were also based on his childhood.

What made this moment so impactful, though, is the way that the animation quietly captures its gravity. A child moving into a new environment is a common scenario in Miyazaki’s works, always lending an empathetic spotlight to children, but the way The Boy and the Heron conveys that tension is unlike any of its predecessors. As Mahito meets his new mother Natsuko for the first time, his conflicting feelings of rejection, embarrassment, alienation, fear, and so on are palpable in his acting; stiff, but in that overly performed, very human way. And with one fell swoop, the weight of that moment is translated to the entire world of The Boy and the Heron—quite literally so.

Mahito and Natsuko call a rintaku—Japan’s cycle rickshaws at the time—to take them to the place that will be his new house. She passes her suitcase to the cab driver, and it’s hard not to notice how realistically weighty it is, how authentically it depicts the effort that you would have to make to carry a packed bag like that. The stunning realism continues to apply to the entire scene, setting it apart from what you’ve come to expect from Miyazaki’s worlds. Just that moment is enough to clue you into something: this film has some baggage that not even the animation is free from. And it doesn’t fight that, but rather embraces it, because it’s integral to its identity.

Weight. Miyazaki’s animation, which is to say his storytelling, has a curious relationship with it. As a great disciple of the late Yasuo Otsuka, it’s not as if he turns a blind eye to physics. If anything, he has mastered ways to make animation continuously reactive and consequential in ways that few others can imagine, let alone execute. Especially as his career as a director progressed, though, Miyazaki took a liking to reformulating the laws of each of his worlds according to their narrative and tone, always landing closer to the fantastical end of the spectrum. The magic of these settings is sustained by the general properties of their animation, which evokes life by being bubblier than any reality.

This much has been true for as long as Miyazaki has been chief director. One of the aspects that made Future Boy Conan so captivating when I first watched it, and in some ways scary—what can I say, I was very young—was the impossible physical feats that still felt rooted in something. In contrast to the more bombastic cartoons I watched at that young of an age, its world clearly still had rules about what was possible and how bodies should react to forces. Those were simply different ones, conceived to fit this specific adventure, as you would expect from Miyazaki and Otsuka teaming up. In a more lighthearted way, similar things can be said about Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro, which sets the standards for its hijinks with a blatantly Otsuka-esque setpiece at the start; just compare Tsukasa Tannai’s physics-bending hurdling to classic Otsuka work in the series.

In that process of redefining the rules of the world, flight is a recurring topic in Miyazaki’s works. It’s a rejection of gravity, and also happens to play into his complicated love of planes and flying devices, so you can bet he made a bunch of movies with that idea at their core. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind often defines its unique fauna through this ability, its protagonist through her status as a wind-rider, and her society as one in harmony with the wind and flight; so much so, that her father growing old is communicated through his inability to fly anymore. It goes without saying that this is all over Laputa: Castle in the Sky as well—the first few minutes and opening sequence are already a relay of ideas to defy gravity as we know it, be it with technological inventions, or through the magical laws of its world.

If I had to point at the movie where it feels like Miyazaki fully marries those tendencies as an animator with his vision as a storyteller, that would be My Neighbor Totoro. Mind you, it’s not a departure from the Miyazaki of the past, as we can immediately see that Otsuka’s philosophy is still in play; actions are still consequential after all, they simply aren’t bound to a realistic set of physics.

The way its paradigm has shifted more towards the dreamlike is visible in the animation of creatures like the soot spirits, but especially of Totoro itself. Just by mentioning this title, I’ve clearly evoked the physics of its titular creature into many people’s heads. Totoro is fluffy and bouncy, to the point where in the iconic bus stop scene, a mere water droplet can make its nose vibrate. That same scene reminds you that, for as many gravity-defying stunts as Totoro pulls off, it’s not actually bereft of weight—it simply plays by its own rules. It represents a world where not just creatures like the Catbus can sometimes leap like they’re on the moon, but the planet itself bursts in a floaty yet still consequential way.

Moving forward, that process of defining each world’s identity through the physical qualities of the animation becomes key to Miyazaki’s filmography. They tend to fall within the same loosely defined zone of blobby cartoons, but the specificities of each one depend on the themes of the film. For an obvious example, Ponyo starts in the sea, but quickly it’s obvious that the free-flowing, liquid qualities of the animation are constantly present on the surface too. As Miyazaki turns his environmental lens towards the water, so do the physics of the animation.

In a similar vein, Kiki’s Delivery Service is another movie about flight and literal magic—as well as the lack thereof—that underlines that this philosophy is not just about literal weight, but how physical efforts are expressed as well. Miyazaki characters aren’t almighty, as they often have friction with their physical limits. To convey those, though, exaggeration is used in a very empowering way—especially considering that both his casts and audience feature lots of children. Kids see themselves in movies that don’t just represent fantastical worlds as they imagine them, but also where younglings are gallant even when they physically struggle; it’s not one heavy object that they’ll sweat to carry, but often a large, almost comical pile of them.

It’s also important to note that what Miyazaki is doing is defining boundaries, which gives him room to adjust not just the properties of the movie’s animation according to the general tone, but of specific scenes according to moment-to-moment needs. Princess Mononoke might be his angriest film, an edge that roots it to reality to a larger degree; you can feel the heavier sense of weight right at the start and across many important scenes, even in more subdued ways like the rhythmic beating in Irontown, but it never makes the full turn towards realism. It’s a given that its fantastical creatures aren’t subjected to normal physics, but what is particularly interesting is the relationship between violence and the properties of the animation. The very first time we see the monstrous strength that the curse has given to Ashitaka, it’s through one arrow shot that cuts two arms and pins them to a tree, causing them to flail around like they’re jello. It’s clear that even at its most ruthless, this world has similarly cartoony, bouncy laws to it.

One particularly brilliant movie when it comes to the modulation of those properties is the aforementioned Spirited Away. Its extravagant, diverse mixture of fantastical ideas determines that it’s free to ignore the binds of common sense, very much including physical restraints on the characters and world. It’s a movie of fluid bursts of free-flowing, unburdened motion, but at the same time, it’s aware of the power of dialing up the realism—like for example, a bowl dropping more realistically to make what has happened to Chihiro’s parents all the more unsettling.

While again, we’re talking about adjustments within a scale rather than flipping binary switches, it’s interesting to see how those concepts are applied to the scariest fantastical beings that Chihiro has to face. In her first real trial at work, we can notice more realistic restraints to her actions, which gradually make way for purely magical animation once she succeeds and it becomes obvious she wasn’t facing a scary (or stinky) foe. It’s quite telling that one of the most famous shots in animation is the Kaonashi, arguably the most otherworldly and scary being in the film, being authentically washed away by a wave. However, it would be a disservice to the movie to imply the modulation is only employed for the sake of creepier vibes. In the emotional climax of the movie, Yamashita’s falling animation has realistic traits to it you don’t see across a movie where people just zoom across spaces, and that has a very humanizing effect: Haku has just been given back his actual name, rooting him in reality, and thus the animation follows suit.

All these ideas are still present in what was Miyazaki’s latest major work until this year. On paper, The Wind Rises isn’t even a fantastical story, as it’s a historical drama that serves as a fictionalized biography for Jiro Horikoshi—an engineer of Japanese fighters during World War II. In practice, though, it’s a movie very much about dreaming. Its first scene feels very physically reactive, but in that floaty, oscillating way that fits the realm of dreams. It’s hard to miss that even after waking up, those properties never really leave the movie, because dreaming never does. One of the most striking examples is the depiction of the Great Kanto Earthquake, a devastating and very real catastrophe that still has that magical undulation to its animation.

The Wind Rises’ awareness of weight and physical limitations on a textual level—it’s a movie about an engineer after all—makes the contrast caused by Miyazaki’s choices all the more interesting. To point out that Japan is lagging behind technologically, the movie keeps noting that their prototype aircrafts are dragged around by oxen. To embody the friction between Jiro’s dreams and the reality of being trapped within the arms industry, he outright says that weight is a problem—so why not just drop the guns, then. All this awareness isn’t enough to visually weigh down Jiro’s dreams, and instead, it’s the scenes that drive him close to his wife Nahoko that emphasize those properties; though of course, in a rather exaggerated way still. In a movie about living in the kingdom of dreams, the one relationship that grounds him is also animated as such.

One of the final scenes in that movie does a great job of combining that Miyazaki bounciness with more grounded details, as Jiro and Nahoko meet at the station. The person who key animated it was Takeshi Honda, who earned the nickname master within just a few years in the anime industry, and then grew onto it in a way that I’m not sure even the person who gave it to him could have predicted. Honda’s animation always had that springiness to it that you’d expect from someone raised at Gainax, with an aptitude for both mecha and character animation. At the same time, he’s also someone who doesn’t just stand toe to toe with the most illustrious realist animators in the country, but often finds himself leading them; jack of all trades, somehow master of all them too, so truly a shishou.

It had been a long-held dream of his to lend his talents to Miyazaki, something he was finally able to do for a climactic moment in Ponyo—earning himself the rare, much-coveted Miyazaki praise in the process. After another successful appearance in The Wind Rises, he was invited to act as the animation director for Boro the Caterpillar, a short film exclusive to the Ghibli Museum and their Park. As they were wrapping up that job, Miyazaki pulled him aside to pitch a more ambitious role, which actually clashed with Honda’s plans to supervise the final Evangelion film. As he has explained in various interviews, with different degrees of candidness depending on the platform, Miyazaki’s insistence that he focus on his project and he does it now made him drop the plans he already had; “no one in my family has lived over 80 years, we gotta do this now” is not a pitch you want to reject from a legend who was close to that number, and has surpassed it across this production.

The project we’re talking about, of course, is The Boy and the Heron. That scene that struck a chord for me was Honda’s own key animation, and his thorough supervision fills the entire movie with similar qualities. Every important step Mahito makes leaves behind a literal footprint, and the burdens he carries have a similarly physical dimension to them. In a movie with a titular magical bird, we still see him realistically stumble, weighed down by a stronger gravity than we’ve seen before with Miyazaki. Between Honda’s role as the supervisor for all the animation, and a few more logical realists in the team than usual, the Miyazaki paradigm is readjusted.

They keyword there, of course, is readjusted. In the same way that it was a mistake to treat previous films as a pure, consistently cartoony fantasy, The Boy and the Heron has hardly abandoned that bubbly Miyazaki-ness, but rather simply dialed it down. Known narrative-spinner Toshio Suzuki has talked about the movie as if he abandoned his position in the animation efforts, but that is Miyazaki’s language, one that he simply needs to make his films. While he may not control every piece of key animation like he did in the past, his designs and concept art still evoke certain fantastical qualities, as do his ever-present layouts, and he still animated some pivotal sequences himself.

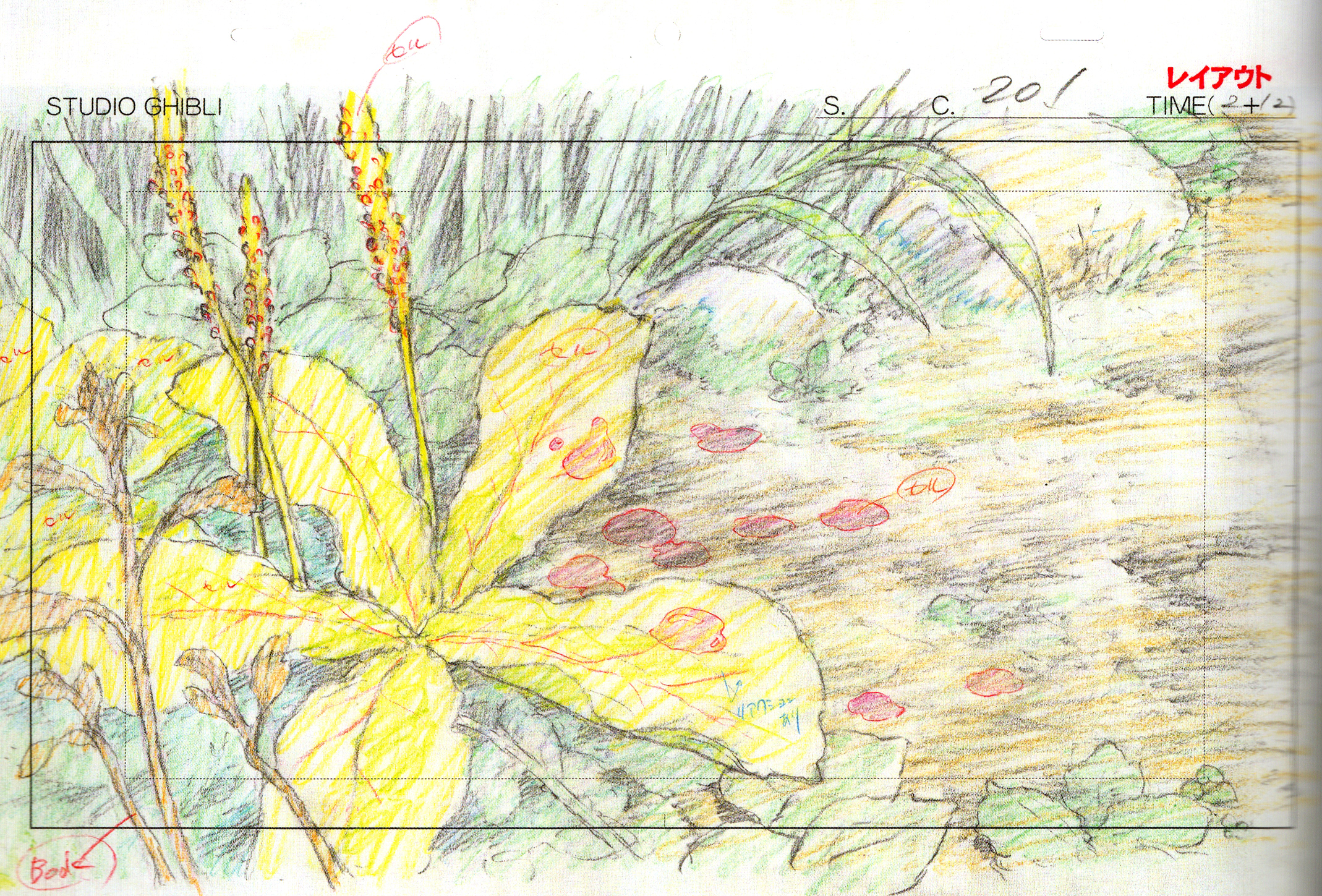

The most (literally) striking example of that friendly tug of war between different styles arrives when Mahito, alienated at his new school as the new rich kid with a father who can’t read the room, hits himself with a rock in the head to have an excuse not to go. The impact is weighty on its own, and details like the way the blood falling physically affects the plant at his feet ground it in a chilling manner. While Yamashita’s work was excellent to begin with, Miyazaki still intervened to make sure the flow of blood was exaggerated in the same way classic Ghibli would emphasize big, blobby tears. The result is awe-inspiring, a mix of concepts that about sums up this film’s visual width.

In Akihiko Yamashita’s layout, you can see a note saying that there is a reaction, with an arrow indicating how the flower should bend under the weight of the droplets of blood.

In Akihiko Yamashita’s layout, you can see a note saying that there is a reaction, with an arrow indicating how the flower should bend under the weight of the droplets of blood.

Especially if you’re acquainted with Miyazaki’s body of work, that stronger emphasis on physical weight makes the viewer start noticing other types of weights in the film. The first scene I highlighted is, no matter how you look at it, psychological weight that Mahito has to gradually figure out how to sustain. Other central characters like Natsuko undergo arcs where they have to avoid being crushed by all sorts of weights of their own, like that of replacing her own charismatic sister as wife and mother. That weight of motherhood that she feels insecure about is amplified, because not only is she adopting Mahito, but is also pregnant herself. As she finally lashes out about all this, in a mix of rejection but also worry about Mahito, it’s once again Honda’s key animation that dials up the realism in stunning fashion.

Physical weights like the one of the suitcase she carried in that first meeting overlap with symbolic ones; its contents were all sorts of items that became increasingly harder to procure during the war, such as white sugar and cigarettes, quite literally making it worth its weight in gold and then some. Weight, weight, weight as far the eye can see. Its visual expression is amplified because of Miyazaki’s adjusted role, but even that ties into the movie itself, which very much feels like one only a weary old creator burdened by their own legacy would make.

In the same way that it’s obvious that the first half of the film has plenty of autobiographical elements around Mahito, the second one clearly mirrors his current standing as a creator. Mahito’s adventures to rescue Natsuko take him to a fantastical world that has overgrown around a central figure: the creator, one who is too old to keep up with the constant tinkering necessary to keep an empire like Ghibli’s still functioning. Just like he personally did, that man has to ponder how to get a successor from his own lineage, and whether that is actually necessary or not. It’s brought to the forefront in such a way that it’s hard to even call it metatextual—Miyazaki’s career and Ghibli’s weight are quite literally what it ends up being about. And as a sly director, someone who at this point only employs people whose skills he knows very well, his decision to strongly seek out Honda at the start and the synergy with these themes feel like they can’t be a coincidence.

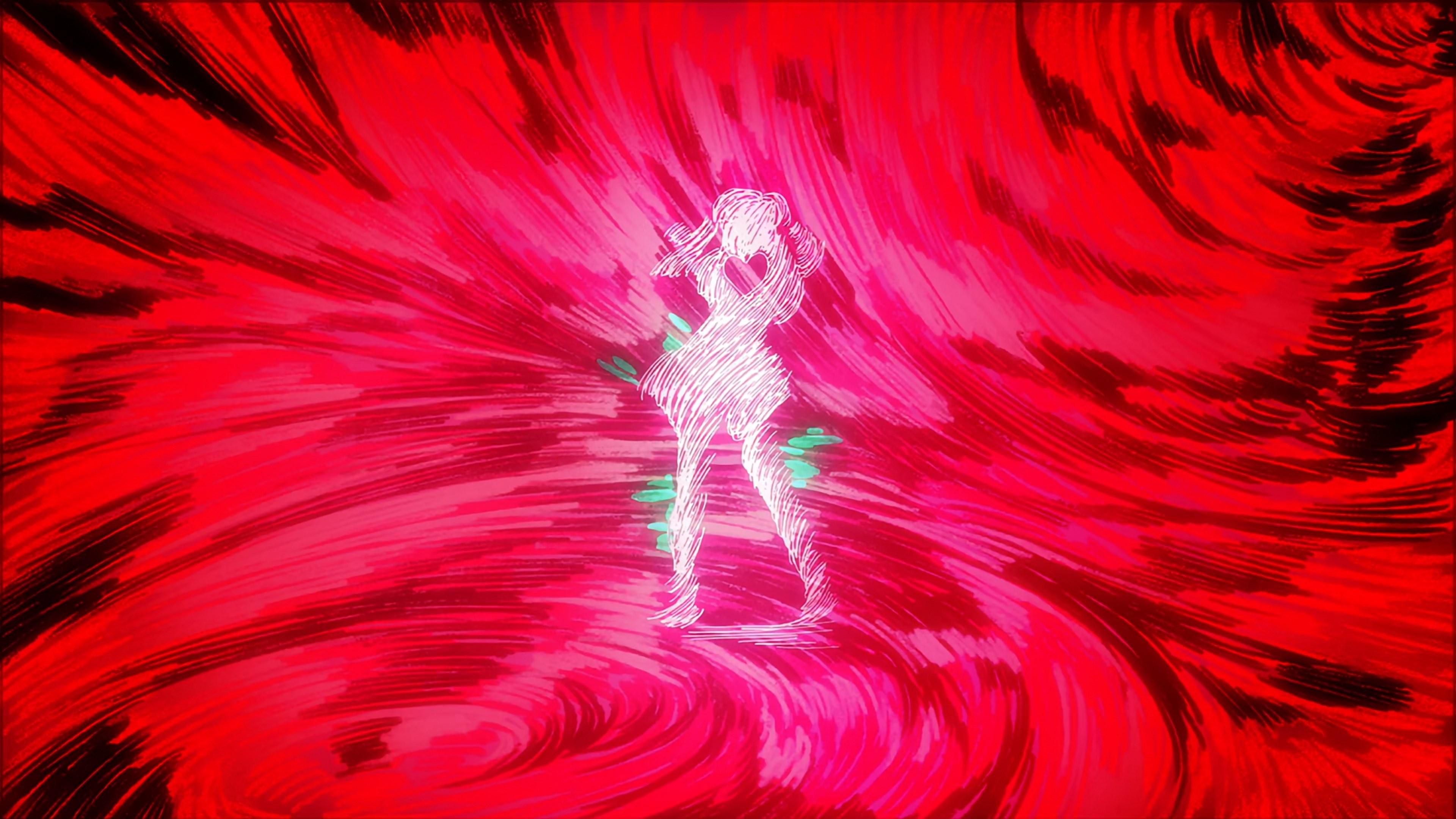

From that angle, the movie’s conclusion is also fascinating. Mahito ends up rejecting the throne, pointing at the weight of his self-inflicted, cowardly injury as a sign of human dirtiness—something not befitting the purity of a fantasy world, but rather of the realm of humans. The Boy and the Heron gestures towards a positive message to continue to live on, embracing the inherently flawed human nature. It once again amplifies that message with physical restraints to the animation, and even a lack of thereof. Across the entire movie, almost everyone is weighed down by gravity, including the many birds in the film. The only ones to break this rule are the Warawara, which once fed, freely float away; according to Kiriko, rising up to the real world to be incarnated into people. If Mahito is right and to live is to sin, to be weighed down by human nature, it makes sense that the only floating creatures in the film are the ones that precede life.

In the end, the creative tower collapses under its weight. The weight of old age, and perhaps of an excess of external factors that have grown beyond control. Miyazaki’s environmental angle in this movie takes up the form of the existence of invasive species, brought somewhere they don’t belong against their wishes and natural tendencies, and still worthy of living despite their potentially damaging position in those environments. The most notable of them all are the parakeets that have taken over this place of creation. They’re amusing, colorful, but also dumb, incapable of meaningful creation themselves, and yet always hungry—something that friends of mine have likened to the merchandise empire that has grown around Ghibli themselves, who at points have been more of a Totoro plushie factory than an animation studio. If that is where we’re at, maybe it doesn’t make sense to obsess about keeping Ghibli going.

There are many reads you can make of this movie, which is far too complex to perfectly track each allegory to one real concept. Many conflicting ideas coexist in it, and that’s what ends up making it so interesting. The Boy and the Heron is certainly not Miyazaki’s most formally polished movie, but with its conversation with the director’s extensive filmography, and by matching the properties of its animation to many of those ideas, it’s certainly his most weighty film.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, Sakuga Video on Youtube, as well as this Sakuga Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!