It’s time to talk about the somewhat confusing, misunderstood shifting labor and creative dynamics of Spy x Family’s co-production, how Kusuriya no Hitorigoto is able to elevate from a solid adaptation to an exceptional one, and more! The Evolving...

It’s time to talk about the somewhat confusing, misunderstood shifting labor and creative dynamics of Spy x Family’s co-production, how Kusuriya no Hitorigoto is able to elevate from a solid adaptation to an exceptional one, and more!

The Evolving Co-Production of Spy x Family

The shared duties between Studio WIT and CloverWorks to bring Spy x Family to life have always been a topic of interest for us, hence why we wrote a lengthy article explaining the circumstances that led to this co-production; those being that WIT, the studio that the project was initially pitched to, was so busy it led to producers on their side contacting friends over at CloverWorks to organize a tag team approach. With not just the second season but also an original movie arriving at the same time, their strategy has only become more interesting—and the misunderstandings around it have only intensified. Given that those studios are led by individuals who gladly misrepresent the situation to endear themselves to an audience that doesn’t know any better about their messy management, that’s plenty of motivation to shed some light onto the truth.

Mind you, people are somewhat on the right track, as the idea that WIT will produce the movie while CloverWorks spearheads the production of season 2 instead seems to have gained traction. While that is mostly true, though, the internet’s lack of nuance makes people miss important points; for example, the fact that WIT still leads the alternating production order this season, or that they’ve found ways to put together the most vividly animated episodes thus far. As usual, a lack of familiarity with the language and production practices can lead to entirely wrong conclusions as well. Since it was already publicly anticipated that the leadership roles for season 2 would swap, some people seemed to misunderstand its premiere as having been produced by CloverWorks because of an animator being listed under their name… when his studio was specified like that because he was a guest appearance within a WIT episode. To understand how things have changed, then, let’s quickly recap how they used to work.

Spy x Family Season 1 was captained by series director Kazuhiro Furuhashi, appointed by Studio WIT. Most aesthetic departments were also led by creators adjacent to WIT, though with some important nuance to this: there was always an assistant to the leader who was closer if not directly employed by CloverWorks instead, and that same dynamic was flipped for the animation supervision, as the character designer is Kazuaki Shimada—someone close to that specific CloverWorks team. Each individual episode was then produced by either studio, with every step of the process handled by each of those factions of sorts; that is, their in-house personnel, as well as subcontracting to groups they are particularly close to. Though the two main studios did help each other on occasion, the division was fairly clean, compartmentalizing all the workload to one of the two studios each week as they alternated.

This division of labor appears to spell out a perfectly even co-production—at least once the animation phase kicked in—but the truth is that the initial plans kept tipping the balance towards WIT. Though the difference was never massive, they had a bit more on their plate by sheer volume, and consistently pushed the accelerator harder in their delivery; in the first cours in particular, almost all highlights corresponded to WIT episodes and animators like Keisuke Okura. Even the two instances of full outsourcing hinted at their greater intervention on a planning level. The first half was brought to a close by the Madhouse team both of them had helped in Sonny Boy, while the second one started in the hands of studio Colorido, whose relationship is notoriously stronger with a WIT team that had yet again assisted them on a theatrical production. If we were to put arbitrary numbers to this whole situation, it would be a bit more of a 60/40 co-production than a perfect 50 split.

What about the sequels, then? The upcoming original film may not be directed by Furuhashi, who is instead taking a supervision role, but his replacement being an in-house WIT member like Takashi Katagiri should already tell you where things are heading. Though some CloverWorks help wouldn’t be unreasonable, the team surrounding WIT’s animation production Kazuki Yamanaka—the same AniP behind Ryouhei Takeshita’s wonderful Pokemon Paldean Wings, incidentally—should lean harder in their direction than Spy x Family ever has before.

Knowing the fate of the movie, it would be reasonable to expect the opposite trend for the TV show. And indeed, even its core staff was modified to favor the CloverWorks side of the equation. Remember the arrangement for the first season, where all aesthetic departments had a leader from WIT’s faction, and an assistant closer to CloverWorks? Season 2 adjusted all those roles so that the leadership falls onto the latter camp, and unlike the alternation of the first season, most of those tasks—such as painting and background art—are pretty consistently spearheaded by the same CloverWorks-adjacent personnel. In that regard, the dynamic has flipped to the opposite direction and then some.

However, it didn’t take longer than one episode to prove that things aren’t as simple as CloverWorks taking over the TV show. As previously mentioned, the first episode of season 2 was produced by WIT instead; with a certain SatoSute as a guest helper, and additional tasks further down the pipeline handled by CloverWorks-adjacent staff, but a WIT episode nonetheless. In essence, the adaptation didn’t change either, though you can feel that the standards have been lowered somewhat to make up for the existence of the film. Even without comparable highlight sequences, though, Furuhashi’s boarding still makes for an inherently amusing presentation. Throughout this adaptation, he has been at his best when he’s had the room to take detours, so going back to a past short story to open up the season was a pretty reasonable choice.

Moving onto the second episode, we get a taste of CloverWorks’ actual work in season 2. Again, it’s not particularly bombastic, but it’s got an efficiency to its delivery that still makes it feel like you’re getting something out of watching this adaptation. The production of this episode has a nice story attached to it, as it’s a landmark in the studio’s training of in-house animators—one that is also significant for their mentor, who was on his way to an early retirement before being offered this position—that we’ll save for whenever we have more time for it.

What is quickly obvious, though, is that Miyuki Kuroki is a damn fine director. CloverWorks’ lower investment in the first season also showed in the renown of the directors they gathered, so starting with an episode led by one of Yuichi Fukushima’s stronger directors does feel like a positive sign. The second half of the episode in particular is quietly excellent, as Kuroki bookends the boys’ short self-discovery trip with similar shots; starting with bright conditions, but a tinge of darkness lurking within the group, then eventually ending at night but with light and warmth having been fostered within. An elegant showcase of what a particularly skillful director can pull off without a tremendous amount of resources.

From this point of view of the division of labor, the third episode’s point of interest comes not just from the fact that it was outsourced, but who it was subcontracted to. In the same way we established that the support studios in the first season were closer to WIT, the choice to lean on studio Snow Drop to handle does hint at CloverWorks having made the call instead. And that does make sense—if you’re the studio with more of a leadership position, you’re also the one most interested in pacing the overall production so that your team(s) don’t grow too exhausted. Such changes are also shown in less apparent changes in the core team; besides changing the order of the animation producers, with CloverWorks’ Taito Ito being listed first now, Spy x Family has gone from having one production desk for each studio to currently only employing Cloverworks’ Mamoru Honda. In short: the internal management is also tipping their way now.

But again, it would be a mistake to assume that this means WIT is no longer involved, as they produced the very next episode without having their turn skipped by that subcontracted intermission. #04 is in fact the most energetically animated episode of the season, with a constant spark to it even without going overboard in specific sequences. What’s the trick to this, then? How could WIT yet again be the studio with the boldest episodes, even in a season where their team has their attention divided? In this case, the trick is something they call internal outsourcing; a term that sounds like an oxymoron, used to refer to jobs rerouted to a different production line within the same studio.

This time around, the internal help came from Maiko Okada—most definitely WIT’s star animation producer nowadays, and a regular topic of conversation on this site because of works like After the Rain and Ousama Ranking, as well as her relationship with exceptional artists that dates back to Parol’s Future Island and Shin-Ei Animation. The more Okada’s reputation has rightfully risen, the more her schedule has filled up, but the studio has still found ways to keep her involved with a title that needs all the help it can take. While Masaaki Yuasa’s opening for this season was produced at CloverWorks, it was Okada’s intervention that allowed the presence of some star animators like Yoshimichi Kameda. Although Kameda couldn’t make it to episode #04—he’s making his own series with this same team after all, alongside another pal of his—it’s very nice to see that Claire Launay is incorporating traits of not just him but also other aces who frequent that team, becoming one of their new aces in the process. Although they’re too busy to expect this help to come consistently, it has already made a bit of a difference.

The latest episode as of publishing marks the beginning of the cruise arc, and also shows a different type of resourcefulness from the CloverWorks side of the co-production. In an era of hundreds of animators rushing to finish every episode, destroying any semblance of cohesive vision in the process, episodes like Spy x Family S2 #05 really stand out; entirely key animated by the duo of Haruka Tsuzuki and Takuya Kawaii, who also acted as the director/storyboarder and animation supervisor respectively, and with virtually no 2nd key animation sprinkling. Obsession over the number of animators is a bad habit we’ve spent years trying to hammer down… and completely failed to, but that won’t stop me from trying to drive the important point: these should help us understand the conditions—strictly labor-related ones but also different understandings of the creative process—rather than being a number we derive absolute conclusions from. And in this case, watching the episode and investigating the team simply spell out the work efficiency.

Tsuzuki was trained as an in-betweener at A-1 Pictures, and has ever since spent most of her career working alongside them and their cousin CloverWorks. While bouncing from one production line to the other, they all seemed to reach the exact same conclusion: she can do a bit of everything, and she can do it well. Tsuzuki has become the type of creator who accumulates a handful of different credits in the titles she participates in at length, proving her ability in diverse animation and direction tasks. Perhaps more importantly for the people leading those projects, though, she quickly proved that she does it efficiently as well; back in 2021, 16bit Sensation’s series director Takashi Sakuma already shouted her out as a godsend for a director, due to her sturdy fundamentals, cost-efficient character animation, and the ability to protect the schedule.

Besides Okada’s involvement, Yuasa’s opening is also notable because of… well, Yuasa, and his funny contrast with a polish-first work like Spy x Family. The goofy posing and timing across the OP brings to mind his classic work on the likes of Shin-chan, but this show’s need to stick closer to the design sheets creates a pretty amusing gap as far as I’m concerned.

Ever since then, Tsuzuki has been getting increasingly more important roles in high-profile production likes such as Fukushima’s. While fans tend to flock to the names behind the most dazzling moments in those, it’s on people like her to give everyone breathing room, while also putting together work that doesn’t feel out of place within productions with such high standards. Having gotten used to that, then, it’s no surprise that she was able to pull this stunt within Spy x Family’s more modest framework. Episode #05 makes great use of those shot construction fundamentals her peers have praised, remains eminently readable about each character’s feelings, and simply doesn’t waste any unnecessary energy. It’s not the type of work that fans tend to notice, but for many reasons, one that anime sorely needs at the moment.

What’s the summary, then? 5 episodes into season 2, it’s fair to say that the bar for the TV show is a bit lower now; understandably so, given that the people responsible for the most bombastic moments of the first season are now making a movie. Everyone is generally busier, in a co-production that was arranged in the first place because all parties were already busy, and that’s simply not ideal. However, some smart management by the people who actually make this cartoon still enables moments of brilliance, as does the competent direction. People have mostly been right in assuming this season is so far leaning more towards CloverWorks, but the specifics have been wildly misunderstood, as tends to be the case. I hope this has made the situation easier to understand… for now, as there’s the potential that WIT will come back to reclaim the TV show after the movie, meaning we might need another one of these in the future.

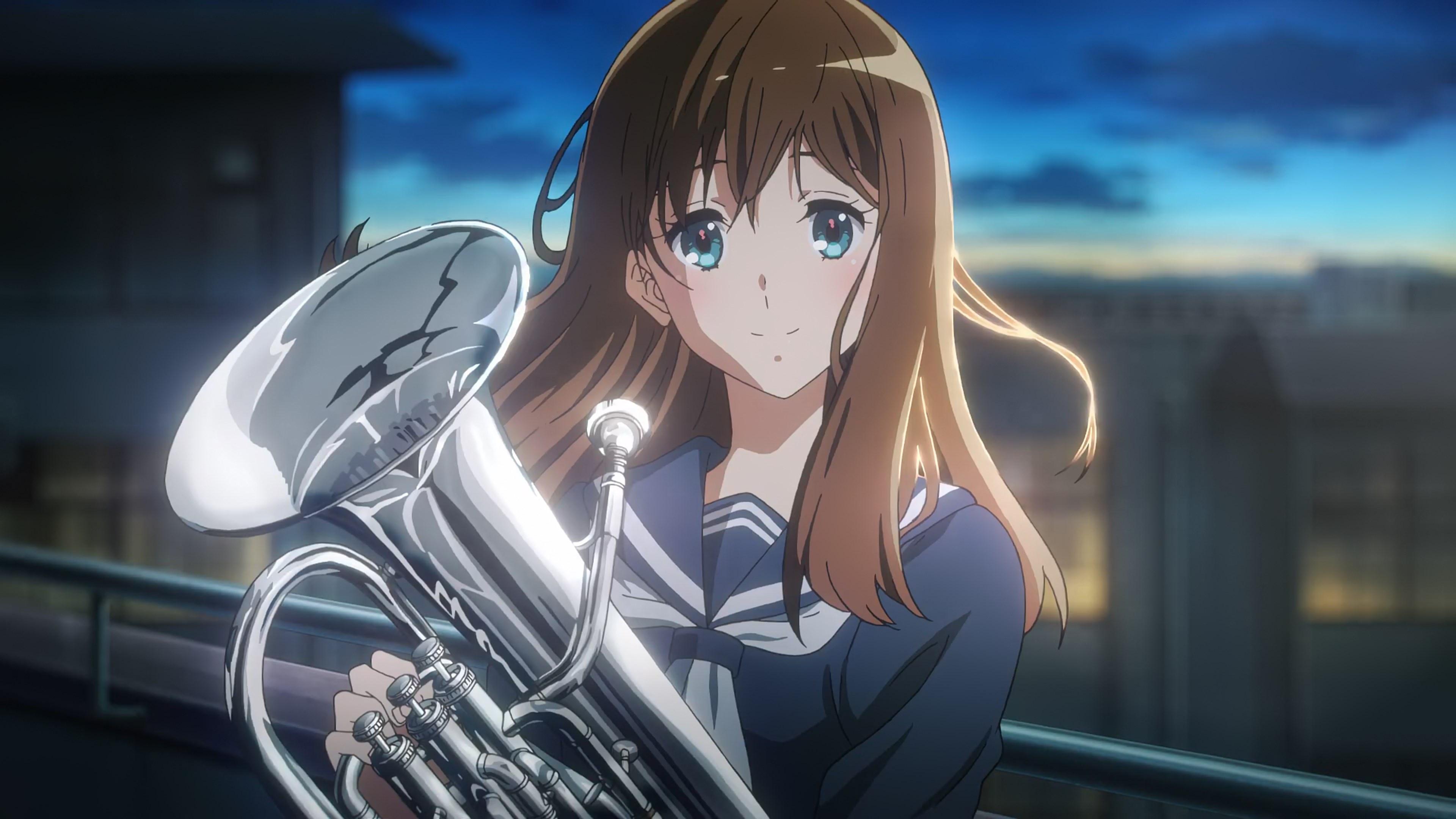

Kusuriya no Hitorigoto’s Anime Is Solid—And Sometimes, Truly Exceptional

I will spare everyone an essay about how Kusuriya no Hitorigoto came to be, about its broader appeal, and what makes its anime adaptation particularly appealing; by which I mean, I’ve already written that, so just go check the previous entry in this column. Today we have a more important topic to deal with: the fact that, in that same writeup, I already called its spectacular fourth episode and its lead actors despite having no specific details. Do I deserve praise and admiration for it? In retrospect, I’m going to tell myself of course not you idiot, it was pretty obvious. So, why is that?

As noted there, the animation producer representing TOHO Animation Studio in this co-production is Takafumi Inagaki. In contrast to the ever-changing but in broad strokes evenly split co-production we just talked about, Kusuriya is a lot more of an OLM product than a TOHO Animation Studio one; the former might be busy to the point of internal catastrophe nowadays, but the latter barely exists, so it’s no surprise to see OLM heading the process. Who are these other people, then? TOHO is a behemoth across multiple industries, but they’re not content with that alone. What they did by purchasing a small 3D studio like I&A wasn’t looking for their specific field of expertise—they’re not even handling the CGi in this show—but rather what the largest distributors in the world of anime have been salivating over: more direct control over their productions and IPs.

While the unsettling potential consequences of that should be obvious, TOHO’s tendency to scout up-and-coming creative stars and their decision to have a studio of their own do have their synergy. To celebrate the 10th anniversary of the distributor’s anime branch this year, they once again gathered a group of beloved, mostly young artists to animate music videos as they pleased. Some of them were good, others great, and one was arguably the short film of the year—Chinashi and Moaang’s Detarame na Sekai no Melodrama, a thoughtful and touching homage to Utena. While the other music videos were made at regular studios, theirs was credited to TOHO Animation Studio themselves, with a certain Inagaki as the production desk. With all this in mind, this exceptional episode starts to make a whole lot more sense.

It’s to be expected that OLM will continue as the leading voice in this adaptation, but reaching this fourth episode, we already have an excellent example of what TOHO Animation Studio can bring to the table: excellent connections, through both a corporation with a knack for that and resourceful individuals like Inagaki. In his latest venture at Liden Films, he had already enlisted Chinashi to make a cameo appearance for the eyecatches in Yofukashi no Uta, so he clearly has the eye for this that TOHO tends to value; incidentally, his ex-Liden partner Ayana Honjou has also been recruited into TOHO Animation Studios, showing up as the animation producer in the aforementioned music video and as one of the production assistants for this episode. When we say that the anime industry is all about nets of personal relationships, it’s for good reason.

All these behind-the-scenes machinations may be interesting, but at the end of the day, what most people care about is how those manifest onto the screen. And, by gathering a team totally unlike the one we’d seen so far, the result was… well, totally unlike what we’d seen so far. Series director Norihiro Naganuma phrased it as an episode that emphasizes the movement—something that does highlight some of its qualities, but that I’d say sells its excellence short. Right off the bat, you can see what he is alluding to thanks to exceptionally thorough, precise character animation. Sequences like Maomao’s poison testing at the beginning of the episode feel like the clearest look we’ve gotten at her expert procedures, and also set the tone for the elegant storytelling that the episode is built upon; look no further than her unusual degree of care for etiquette in that scene, which signals the presence of the emperor in the room way before the camera actually shows him. This chapter of the story touches upon a real tragedy, so appointing a very attentive but also dignified director like Chinashi was the right choice.

Another aspect that immediately stands out, especially in contrast to preceding episodes, is the framing of space and its relationship with the characters. One of the major points from the previous Kusuriya write-up was that Naganuma is a very objective cameraman; across his storyboards for the first episode, that imperial palaces feel big because they quite literally are, but he doesn’t twist the layouts to emphasize this in regards to Maomao and company. Instead, its sense of awe comes from other objective details, like the way the light percolates through complex architecture and props.

Chinashi immediately shakes up that formula with a barrage of layouts that feel more deliberately spacious than ever, with the pointed intent of making Maomao feel small and significant. Within the story, this is something that she’s personally always been a fan of, as she’d rather not stand out in the first place. Even as the emperor himself orders her to heal one of his consorts—with an implied threat if she doesn’t succeed—she’s content with appearing like a lost child ordering people around. Of course, the problem comes when her advice is completely disregarded by those who look down on her; something that even the comedic scenes do a great job of communicating. Fortunately for everyone, except maybe the receiver of a mean slap, this leads to a cathartic snapping that completely twists those framing ideas to make Maomao appear huge and overpowering. Individually, all these scenes are great. In conjunction, when you can realize the overall intent and how they reinforce each other, they’re truly excellent.

The episode continues by making great use of all these qualities, as well as of the nuance in the character art allowed by Moaang’s refined supervision. While previous episodes stuck close to the design sheets for a polished look, this episode rests upon masterful modulation. By default, it stylizes away some of the more superfluous detail in areas like the shading and medium to long shot definition, while evoking just as much if not more as those drawings normally would. The episode then pivots from that cleaner canvas to drawings with bewitching detail when a particularly shocking close-up is needed, or to graceful ways to convey even more information; one of the big points of the episode is conveying Maomao’s growing exhaustion as she does everything she can to save lives, which is conveyed with such economical brilliance you can only kneel in respect.

If you add to that a healthy dose of genuine character acting as the episode flips between social registers, Chinashi’s delicate touch to convey a mother’s love even in such a tragic scenario, and the hilarious gags to give it all some needed levity, you get as excellent of an episode as you could hope for. Kusuriya’s solid writing and inherently amusing interactions make it an easy sell, but it’s in episodes like this that the anime truly reaches a new dimension. Mr. TOHO, feel free to gather more creators of this caliber for special episodes, because I’ll gladly watch them.

After talking at length about such a brilliant episode, it almost feels wrong to mention a simply adequate one, but Kusuriya #05 also happens to be relevant to some of the points we were talking about. For starters, it’s another clear example of that more objective lens that series director Naganuma uses to frame this story; after all, it’s his assistant Akimi Fudesaka who storyboarded it, so it’s stylistically close to that default approach.

On top of that, it also happens to be relevant to the theme of how things get organized and then made. This corner started by illustrating the personal connections that made the spectacular fourth episode possible, but it’s also worth noting that those relationships are also relevant to more modest outings. The fifth episode is another fully outsourced one, something that you need to pace the production of a project like this, which simply doesn’t have unlimited in-house resources. The studio that came in to help? One by the name of Studio Guts, which happens to be the place where character designer Yukiko Nakatani worked for most of her career. Sometimes, it’s necessary to look up management personnel across multiple works to find these threads—and in other cases, it’s as simple as “this was the designer’s workplace for years”. Regardless, it’s always useful to be aware of these things!

Undead Unluck, and Yuki Yase’s Greatness Extending Beyond Superficial SHAFT Mimicry

Fire Force made me realize that Yuki Yase’s charismatic presentation might not be enough to sell me on writing I find kinda abrasive, and tasting Undead Unluck has confirmed that for me—both the fact that he’s being entrusted with titles that aren’t for me, and that his team is so good at their job that I’m still compelled to write about it. It’s well known that Yase leads a faction of ex-SHAFT personnel at David Production, having left their original workplace at a turbulent time and spanning across all sorts of creative and management roles. Being surrounded by like-minded folks certainly helps, but I find the attempts to reduce the appeal of his delivery to “ex-SHAFT director borrows their style” to undersell why his work is particularly effective.

Many creators have come and gone through SHAFT, a fact that often remains evident in their style. Much fewer of those, though, have Yase’s ability to actually recreate what made the original tick. Superficial traits of those aesthetics are relatively easy to borrow, but it takes a thoughtful director to master that uniquely appealing cadence that mixes length, proximity, and intensity of shots to always keep you on the edge; there’s a good reason that Akiyuki Shinbo has to often correct other director’s storyboards to a great extent, despite the broader focus of his position at the studio nowadays. For something that is so recognizable, so strongly codified that they have internal guidelines about the style, nailing it beyond the surface is rather tricky. And Yase has proved to have an aptitude for it that I wouldn’t have predicted when he actually frequented the studio on the regular.

That aptitude does include the ability to insert the illustrative greatness of Taiki Konno’s work whenever possible, yes.

In this regard, it helps that Yase’s works at David Production have been supported by ace animators like Kazuhiro Miwa, who happen to perfectly fit his needs. For as much as SHAFT’s works are characterized by how much mileage they can get out of quirky, still compositions, at their best they also excel at capitalizing on kinetic outbursts; in their case, something that had traditionally fallen upon the likes of Genichiro Abe and Ryo Imamura. As a similarly bombastic artist, but in an environment that allows him to go all out for longer stretches of time, Miwa has been having a field day as the team’s leading action animator. With just enough diversity in the characters’ powers to keep each confrontation fresh, but also not so much abstraction that a traditional approach becomes impossible, he’s been bringing to life one thrilling setpiece after the other.

The suitable team extends to different positions as well. It’s obvious that those who share Yase’s origins are likely to fit right into his vision; Taiki Konno’s unique qualities actually gained recognition at large because of Yase’s works at SHAFT, while the likes of Riki Matsuura are now openly channeling the studio’s greatest director, so you can bet it all comes together very nicely. What’s arguably more impressive, though, is how they’ve been able to surround Yase with other folks who can smoothly slide into this specific style despite not being SHAFT expats themselves. The reason I caught up with the series last week in particular was due to the first appearance of Shuntaro Tozawa, a chameleonic director who can just as easily nail Yase’s approach as he can match the beat of his beloved Naoko Yamada. From his staging to the rhythm of his storyboards, this week you’d be fooled into believing that you’re witnessing the work of someone who studied under Shinbo for an entire decade; not just because of how the episode looks, but how it feels. If you found this enjoyable, there will be more of it to come, and not just from Tozawa.

Will I keep watching it myself? I’m honestly not sure. I do enjoy the action, not just for its animation but also because of the wacky choreographies. The presentation in general does a lot to endear the material to me, but just as often as I experience a scene that landed, I hit another one that just drags me out. Unless a friend is enthusiastic about watching it together, I might abandon it after all. If you’re on board in spite of (because of?) the genre tropes, though, it looks like you’re in for a fun meal. Hope you enjoy it, because this crew is pretty special!

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, Sakuga Video on Youtube, as well as this Sakuga Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!