At its absolute best, Jujutsu Kaisen Season 2 is a focused effort to fully realize its directors’ ideas, from the grandest action to the least perceptible details. But at all points, it’s also something else: a fight against an...

At its absolute best, Jujutsu Kaisen Season 2 is a focused effort to fully realize its directors’ ideas, from the grandest action to the least perceptible details. But at all points, it’s also something else: a fight against an asphyxiating schedule. Let’s catch up with one of the biggest, coolest, but also most troublesome productions of the year.

Before the broadcast of Jujutsu Kaisen Season 2 even started, a certain notable voice in the anime industry pointed out the tangible negative effects that, in their view, the preceding movie Jujutsu Kaisen 0 already had on workers. That film may not always stand to technical scrutiny to trained eyes, but for the broad audience it was marketed to, it was a massive success—one achieved by dedicating little time to its production, and even less so to the planning process. That person wasn’t speaking without knowledge: they’re acquainted with many people who participated in the film, they’ve gone on to work with that team after JJK0’s success, and currently find themselves as someone who needs to make sure JJK2 meets nearly impossible deadlines. When they say that they can feel that ruthless producers have become more emboldened by the success of poorly planned projects like JJK0, it’s because they’ve personally felt the effects.

This is an entire dimension to the conversation around messy productions and labor that people tend to ignore, so if nothing else, that harsh reminder is valuable. You might think that audiences being aware of these nuances and of production circumstances in general isn’t particularly important, but the studio themselves would disagree. It’s no secret that an important part of their recipe to success has been to market themselves as winners, hence why they’ve recently done things such as dangle the threat of litigations to these creators keeping a production in the ICU alive, just because they weren’t being quiet enough about their struggles; something they did not just to the person who made that original comment but some other peers, leading to eloquent middle fingers such as “if you don’t want workers to speak badly, why don’t you create an environment that won’t make them do it”, or straight up advising young staff to at best ride their popular titles to make a name for themselves and then abandon them forever.

Mind you, no individual person’s experience is necessarily representative of what the process was like for everyone; you can be a lucky guest in a doomed project, get screwed within a production that largely worked out without pain, or simply suffer through the unique struggles of a specific position. Unfortunately, the sentiment behind all those complaints is one that has been attached to right about every comment I’ve heard from people working on JJK2. It’s not just those vocal creators, not just the ones who keep it more private, and not just the people in the team I’ve talked with daily for months—it’s pretty much everyone, especially if they find themselves in a core staff position, where they have to make sure all materials are delivered and somehow polished up to the bare minimum technical standards.

The fact that a lot of people, including the often more critical artists and animation nerds, find themselves appreciating many aspects of the resulting work speaks about the skill and effort of the team behind it. But don’t get it twisted: JJK2’s planning has been demonstrably cruel, and for as brilliant as the staff’s vision can be, their execution is fundamentally compromised; what started with shortcomings they could navigate around with grace went on to become rough edges they couldn’t simply hide, and by now, even placeholders for entirely missing or unfinished cuts are a recurring issue.

It’s impossible to avoid mixed feelings when seeing a team full of apologetic artists who know they’ve left some of their more ambitious and compelling ideas on the cutting floor, or have seen them nerfed beyond recognition amidst the rush to meet deadlines, when it’s still resulting in a much better produced work than you could reasonably expect from its schedule. There’s a bitter aftertaste when you see some among them blame their own ambition for this situation, when they’re in this position because their ambition made them stand out and earn a position in a high-profile production like this. Meanwhile, everyone with actual responsibility over this mess will leave the project unscathed, if not straight-up reinforced. MAPPA will still be the renowned action anime studio of the moment, and everyone on the committee will get to pat themselves on the back for another job well done. That is what the original comment wanted to warn people against, and why these companies want to control the discourse around their titles.

With that mandatory warning out of the way for now, though, let me make one thing clear: the first arc of JJK2 is simply excellent, in spite of those circumstances. Now, it’s not as if those production problems only manifested out of nowhere at a later point. You may think of the rough edges in animation as a high-frequency noise that is always there; one everyone has different thresholds to perceive, to become mildly annoyed about, and to find deafening. Unlike your hearing, it is something you can train to be more perceptive of… though as some people in the business and avid watchers can tell you, that’s a deformation profesionnelle you don’t necessarily want, because it can be hard to turn off that part of the brain.

In the case of these first five episodes under the Hidden Inventory/Premature Death arc, the delivery was so engrossing that I couldn’t spare a second to think about the buzzing noise of any cut corners or unpolished details. Its exceptional execution embodies the growth of an artist we’ve covered on this site as he has gone from a promising newbie to a technical innovator, then a budding director who built upon everything that made him stand out before. By now, Shota “Gosso” Goshozono is a complete storyteller of a kind you can’t take for granted in TV anime, and a series director capable of raising the entire floor of a production despite this being the very first project he leads.

There’s an obvious temptation to judge JJK2 in contrast to its predecessors, as there’s an attempt to reinvent the series that you’d rarely ever see in an active, very successful property like this. And I will try to avoid doing that as much as possible. Not just for a matter of respect—it’s not only the sequel’s team who had to deal with dubious planning—or because I think that JJK2 is full of work that stands as noteworthy on its own, but also because I think that it’s built in a way that greatly benefits from holistic appreciation.

We can look at individual aspects that have changed in a major way, often associated with a replacement in the leading position of a specific department; some are adjustments involving people who were already part of the team, like the appointments of Eiko Matsushima as the actual color designer, while others are newcomers that can easily be traced back to the director, such as new sound director Yasunori Ebina—a position he occupied in Ousama Ranking, where Gosso truly found his footing as director.

Even accounting for the individual changes I find most significant and aesthetically pleasing, like the heavier stylization in Sayaka Koiso’s revision of the character designs, looking at them in isolation fails to illustrate the greatness of the choices behind them. I can say that I find their look more appealing, or that through their focus on easy-to-parse silhouettes and evocation over constant explicit depiction, they’ve made this troublesome production somewhat more manageable. It’s only when you experience the show, though, that you get to appreciate how nicely they interact with every other piece in this puzzle.

Following this example about the designs, you realize that it’s not just that they synergize with other visual aspects like the moodier lighting, but also play a tangible role in the storytelling efforts; for example, by providing a perfect middle ground for the animators to iterate between horror and comedy as the story sees fit, while a less finely-tuned level of stylization would fail to make that feel like an organic pivot. Though I wanted to keep comparisons to the minimum, I will concede one that sums up why I feel so positively about this team’s approach: while I didn’t feel like this was truly the case before, all aspects of JJK2 coalesce not just into one world, but one worldview. This well and truly is Gosso’s Jujutsu Kaisen now.

If we jump onto the first episode of season 2, it’s easy to illustrate what all of this means in practice. Right off the bat, the moodier lighting and more down-to-earth processing of how it interacts with bodies brings attention to Geto’s shifting shadows as he walks—but details like the organic jitter in the 2D background animation still keep it rooted in a feeling of handcraft. As he describes the routine that has worn him down, the lonely grind that is driving him insane, we see a close-up of his face. It evokes realistic ideas, and yet it’s achieved through purposeful and controlled additions, so it doesn’t feel like it’s straying all that much from the spirit of the design sheets. An increasing buzzing noise that matches his growing unrest, monochrome tones embodying the repetitive nature of his actions—only illuminated in bright, colorful blue flashes when he’s using his sorcerer powers—and Gosso’s grasp of three-dimensional environments used to frame the world as oppressively as Geto perceives it. Many of these choices are immediately effective and clearly in conversation with each other, and they only become more pointed when they become building blocks for JJK2’s language. That is what Gosso has given the show.

A very important point to underline is that the fact that JJK2 has a much better-defined identity doesn’t mean it’s stylistically monotonous. In fact, it’s the exact opposite. By having that clear sense of self, and bringing design elements to a more natural pivoting point, it’s able to constantly switch registers in a more poignant, impactful way, while still feeling like it’s just at a foot’s length from its natural state.

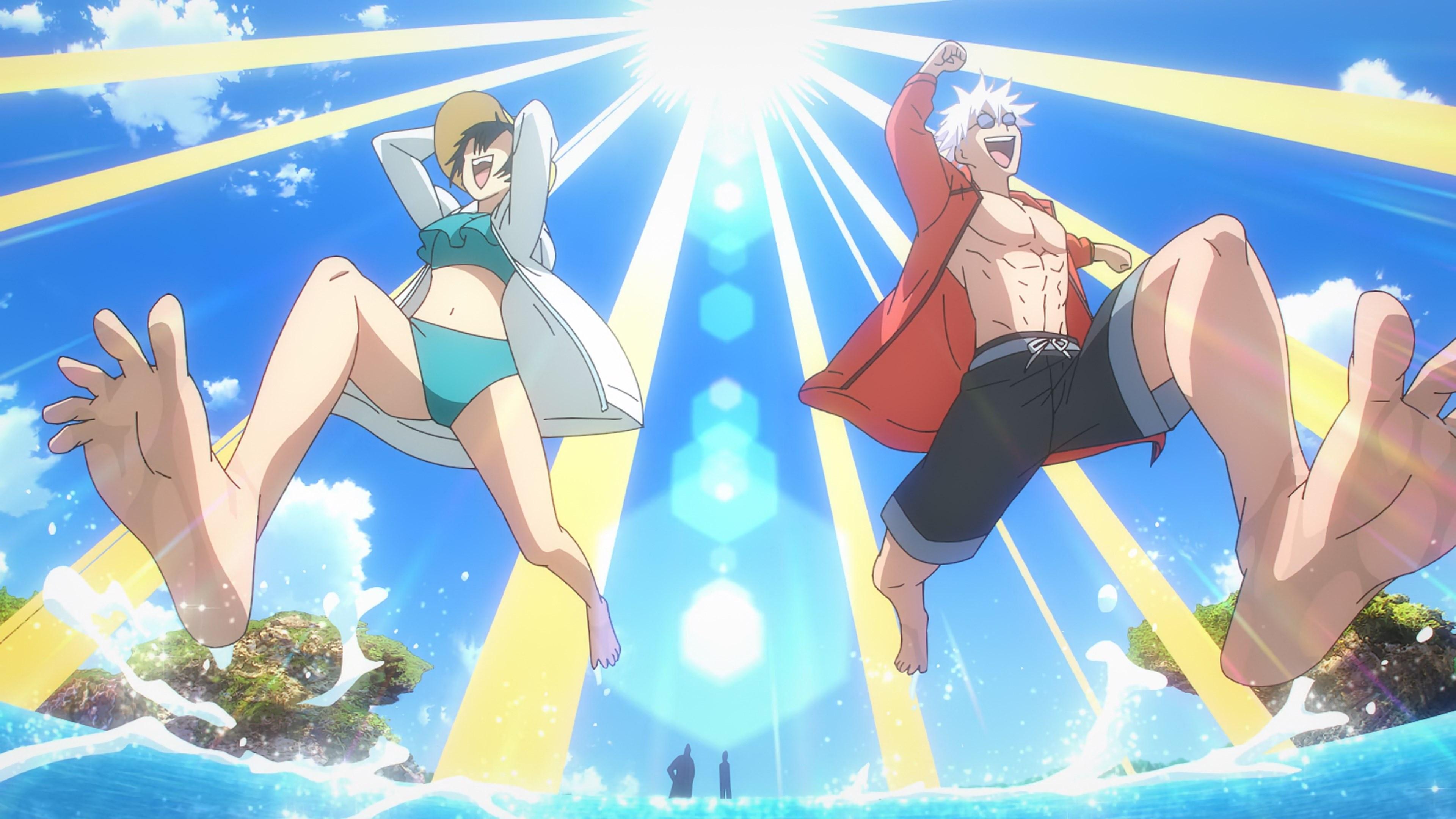

The first episode toys with horror movie concepts as the flashback moves from the tease of Geto’s downfall back to a younger Utahime’s mission at a clearly haunted house. We have great depictions of genre tropes like an incredibly authentic found footage tape, and framing decisions like the constant overhead shots that imply they’re being watched. Its better awareness of the specific toolset of animation allows it to evoke similar feelings through the unnatural smoothness of Utahime’s venture into the mansion being on the 1s, or by again regulating the level of realism in the artwork thanks to specialists like Hokuto Sakiyama. A harsher pivot, though one that feels like it’s still playing within the boundaries that have been established, takes us from a more realistic 3D rendition of the environment they’re trapped in to Paprika-flavored cel bonanza as they escape, with the arrival of the actual protagonists: an even more irreverent young Gojo, an extremely laid back Shouko, and Geto, whose eventual turmoil we’ve already been introduced to.

The two boys in the group, already quite powerful by then, are quickly entrusted with protecting a teenage girl… and eventually guiding her to her death, as she’s meant to be a sacrifice to maintain the current world order. Through their briefing and symbolically staged—though very naturally acted—conversations, we grow acquainted with their standing on these issues. Perhaps surprisingly, it’s Geto who has the sturdier moral backbone; something that, as we’ll see across this arc, actually makes him more prone to having that worldview crushed.

Purposeful delivery like this shows that the team Gosso leads doesn’t just make poignant choices in the storyboard, direction, and animation phases, but that at the show’s best they’ll already have rerouted the script to maximize the potential of those moments. Take another moment-to-moment quality like the sound direction, which the very first scene already established as something that this season is using in smarter ways. As they start their mission to protect soon-to-be-sacrificed goofball Riko Amanai, amusing choices in regards to the audio keep being used to underline the contrast between a supposedly deathly mission and the silly situations they keep stumbling into—but again, the best examples are those that show the craft is deliberate at a higher level as well.

The episode, this time boarded and directed by Yosuke Takada, keeps note that Riko should be in music class while assassins target her. After Geto intercepts one of those pursuers and a bombastic battle ensues, its final twist has the assassin meet his childhood dog. Is the choir music building up to the punchline that he’s simply seeing his life flash before his eyes? Well, yes, but it’s also because the episode remains mindful of that larger context it took note of, so the music continues beyond his beatdown to eventually become diegetic sound. Riko was indeed at the chapel, where we’re treated to another amusing pivot in the animation for a series of amusing gags that just never seem to end. It’s obvious that this entire arc is flamboyantly executed, but just as important is how every preceding choice appears to be very well thought-out—even when they’re just leading to comedic scenes.

Another aspect of this production that is quickly obvious is how much responsibility has been placed on up-and-coming staff making their debuts; unsurprisingly so, given that Gosso himself is leading a project for the first time too. This is best embodied by just how many people are directing and storyboarding an episode for the first time, which is an exciting prospect as well as a double-edged sword. While the series remains at its absolute best in the first arc, we get a sweet taste of that potential. The aforementioned Takada penned his first storyboards in the second episode, but the best early example comes from Naoki Miyajima’s debut in that position and as episode director in the third one.

As Gojo tries to make sure Riko enjoys her final days, the episode feels particularly keen on capturing moments; the way it does emphasizes the role of the color script, one of the tools introduced to this season to boost that cohesion, though one that each director is interacting differently with. Given Miyajima’s body of work, it’s not particularly surprising that when things start going south we’re treated to some cool action, especially as it comes from the hand of aces like Kosuke Kato and Keiichiro Watanabe. It’s that finesse with the subtler aspects of storytelling, though, that makes an episode like this such a pleasant surprise. Even knowing that Miyajima had proven to have the touch to animate efficient acting, you can never take it for granted that this will translate into the ability to reinforce the story you’re telling from a higher position. Much like Gosso is doing on a series direction level, debuts like this embody the upside of trusting young creators. Wouldn’t it be nice if it was always like this?

Though of course, it’s not just youngsters leading the charge—sometimes, the series director happens to have recently befriended a world-class action superstar in their preceding job, hence why the fourth episode is in the hands of one Arifumi Imai. Though he doesn’t have extensive directorial experience on paper despite that status, Imai’s role across Attack on Titan had already put him in the position of making storytelling choices through animation. As we discussed many times in our coverage of the series, the way Imai entirely defined an action style that is now known across the world, and how he would storyboard climactic moments himself as early as during the promotion cycle, already gave him responsibilities far beyond what is assumed an animator does. His resume may not say that he was directing, but he was.

That experience is important not just to understand why he was able to slide into such a finely directed arc, but also because he carried so much stylistic baggage from that series that a genuinely tragic episode had a curious level of humor hovering over it for me. I was as pissed as everyone else when seeing that Riko’s decision to live on was met by a very disrespectfully timed bullet. As Geto snapped in response, the increased scale of the action setpieces certainly felt appropriately Imai-esque too. But it wasn’t until the imagery literally out of Tetsuro Araki’s book that I realized I was genuinely watching an episode of Titans. Though in some aspects it’s not as refined as the rest of the arc, it’s as impactful as any and then some, and actually uses those Araki-esque traits to introduce the most high-concept lore thus far; fueled by rage and in his near-death experience, Gojo has finally mastered his powers, truly becoming the strongest now.

It’s Gosso’s own storyboards that then take us to the ending of this arc, wrapping around every single idea that the story and his directorial choices had introduced. One year later, we see that Riko’s death has heavily affected both Gojo and Geto. The former has obsessively trained, and in the process simply transcended humanity—an inherently alienating position, as the storyboards that always set him apart remind us. The duality with his partner that the storyboards have reinforced since the first scene in the season then literally flips to contrast his growth to Geto’s downward spiral. Familiar sound cues signal his worsening mental state, though it’s the animation direction that does an exceptional job of summarizing why that happened.

After seeing an organization of regular human beings ruthlessly and so casually take away Riko’s life, and beaten down by a job where his peers may die at any moment, Geto has started obsessing with his perceived dirtiness of the masses he is supposed to protect. Just like the first episode already pivoted between degrees of stylization in the drawings to evoke specific moods, Geto’s subjective vision is represented through the hyperrealistic character drawings; especially those supervised by Takuya Niinuma in the first half of the episode, though similar ideas are nicely followed upon in the second one by Souta Yamazaki. Draftsmanship on this level is worth appreciating on its own, but this is the type of show that wants you to think about the specific choices that have led to eye-catching sequences like this.

A beautifully framed conversation with noted weirdo sorcerer Yuki Tsukumo illuminates that Geto is still not far too gone in his hatred of the regular populace, but rather that this is just one of the possible paths ahead of him, just like sticking to his original moral principles still is. Unfortunately, bringing this up also makes Geto more conscious of the possibility of lashing out, thus putting him closer to his breaking point.

More of his comrades die, and what for? In his eyes, for the sake of cruel people who lash out at people with special powers just because they’re different. The dehumanizing framing as he witnesses one last act of cruelty tells us where his view is now. Remember how the very first shot of the season was of his switching shadows? Those two possibilities ahead of him that Yuki mentioned are now represented with two candles, and two shadows—one much stronger than the other by now. As he makes his decision, only one is left; his true feelings moving forward, as she’d described it. Elegant but chilling imagery depicts his massacre of a whole town. It’s all dyed blue, the same color that brought any life to the first sequence in the show. Everything about this arc was already encapsulated in the first minute and a half.

After the first domino piece falls, everything has already been set in motion. Gojo also feels a need to change a world that has led to this situation, but his more compassionate approach will attempt to tear the structures of power from within, while Geto is… a bit more genocidal about it, let’s say. And yet, there’s still some warmth to his motivations, as this arc has made it clear that he’s not just a gleeful mass murderer. Geto was originally a person with strong convictions, but casual cruelty and a faulty system that isolated someone who desperately needed company broke him. A compelling scenario, elevated by keenly focused execution. I have the feeling that I will remember this as one of the most thoroughly excellent arcs in shounen anime.

And so it comes, Shibuya Incident; in some ways, the Shibuya Incident incident. As a fan of Yoshihiro Togashi’s work, I’m predisposed to enjoying an arc where Gege Akutami leans into such Hunter-esque storytelling, taking us step by step in the villains’ plan to seal Gojo via a heavily multithreaded narrative. And mind you, I am enjoying it, but it’s clear that it’s not being fully realized in the way that HI/Premature Death was. This is where I feel that it becomes inevitable to return to the theme we opened this piece with: disastrous planning getting in the way of the team’s ambition.

Some among them put part of the blame for their struggles on those high aspirations and thus themselves, but like I said earlier, that is the wrong angle to judge the situation. MAPPA’s selection of directors for projects like this isn’t motivated by the knowledge that they will do a great job at the role, because they keep selecting people who have never handled it. Instead, the obvious trait they share is being eye-catching animators who will have the type of gravity that attracts other flashy, ambitious artists if they’re to lead a project. As Gosso has proved, that doesn’t mean they can’t pick excellent storytellers regardless of the motivations, but it’s worth keeping in mind where this all comes from.

When people in teams like this run against the unforgiving wall of deadlines, it’s hard to blame them in any way for dreaming high; for starters, because that wall is unreasonably close anyway, but also because these networks of ambitious artists are targeted for these qualities in the first place. Gosso could have cut major corners in HI/Premature Death, maybe sacrificing a bit of that thoroughness that characterizes its every aspect in favor of more breathing room for later episodes. But doing so wouldn’t have turned the schedule into a comfortable one—and maybe more relevantly, if he were the type of creator with a penchant for cost-cutting, he likely wouldn’t have gotten the opportunity to direct this show in the first place. Blaming him, as well as any other episode director across Shibuya Incident, misses the actual sources of strife.

That is also to say that Shibuya Incident is by no means less ambitious than the first arc. In some ways, it might be more so, which doesn’t exactly play nicely to the quickly deteriorating state of the production. I would say that it’s akin to maintaining a similar ceiling—one so high that sometimes you wonder if it’s even there—but having the floor completely collapse. There is a very high baseline level of technical quality across HI/Premature Death that Shibuya Incident fails to protect since early on. It manifests through the plummeting quality of the in-betweening, an erosion of the cohesion that made the start feel so special, an increasingly more uneven level of draftsmanship to the drawings, and eventually you can’t even be certain whether some shots you see on screen are even close to the original idea; having seen the materials for some of those axed shots, no, they are not.

If you’re expecting me to punch down on specific instances, though, I’m happy to disappoint; explaining at length how creators are victims of circumstances beyond their control and then pointing fingers at the consequences wouldn’t be all that coherent. The much more straightforward and action-heavy nature of the arc gives less room for nuance like we see in the first one, but it’s not as if the guiding principles behind it are all that different. Ryouta Aikei opens it up with an episode that plays unsurprisingly close to Gosso’s book, as you would expect from an assistant series director who already helped him in the first episode. It finds its real groove with the emphasis on color and evocative compositions as a classmate who crushed on Yuji’s honesty meets him again, forced into some introspection of her own. The highlight that really gets the arc started, though, is a smartly edited sequence that reveals the villain’s mole among the students; the complimentary lighting being part of the sleight of hand is a great trick, though I almost wish they’d swapped the colors so that Yuji opened a red empty room while Mechamaru’s correct location was bathed with green. Comedy can’t always win I suppose.

For its rough corners, the following episode stands out for the decision to match the mecha theme—as Mechamaru pushes back against the villains he made dangerous deals with—to an abundance of Kanada-style animation, a common broad approach to the genre; for this, we mostly have to thank debuting co-episode director and storyboarder Yooto, who had already animated a bunch of cuts in similar fashion for other episodes. Unfortunately, it’s not the time for heroism to pay off yet, so the villains march forth with their plan to seal Gojo’s terrifying powers. Their plan is to exploit the massive presence of civilians in Shibuya to celebrate Halloween, which means it’s time for my actual favorite part of the episode: the genuine horror film vibes in Takafumi Mitani’s naturalistic crowds, which go from their partying to panicking when they start realizing that something is clearly wrong.

Things get rougher for the protagonists moving forward, and even more so for the team behind the show. Rather than the likely most controversial episode in Hiroyuki Kitakubo’s #08, the one I believe best exemplifies this is the following one, as it marks the return of Gosso to storyboarding duties. He’s still an ingenious storyboarder, pulling tricks like reframing a flashback to the villains planning the operation as a casual mahjong match for comedic purposes. Minutes later, as the plan to exhaust Gojo comes to fruition, Geto reveals his actual winning hand; not the yakuman I’d have chosen to represent gates when chuuren poutou is right there, but neat delivery regardless. As you’d expect from his storyboards, fights operate on a three-dimensional, mind-bending space, with that latter sequence by Daniel Kim also being a treat when it comes to expressivity—both in the palpable desperation of Mr. Volcanohead, and the terrifying nature of an unbound Gojo.

With such proximity to a much fuller realization of Gosso’s ambitions in the previous arc, though, episodes like this are also a reminder that the execution can no longer live up to the vision of the creators; not just in sheer ambition, but in the case of someone like Gosso, in the ability to connect every dot like HI/Premature Death did. Takada’s return for episode #10 follows a similar note, as a director we’ve seen leading thoroughly excellent work, but that at this point leaves behind mostly isolated moments of greatness instead.

In a way, it helps that at this point in the arc we’ve descended into nearly pure action. Sure, that means that basically every episode is demanding production-wise, but bruteforcing spectacular fighting with little time happens to be a special skill of many people in this team. Even as the more subdued qualities drown in a sea of increasing technical issues, episodes like #11 still have quite a lot of entertaining action, as they’re built around specialists like Hayato Kurosaki; even with rougher edges, and storyboards that don’t always fully connect, the spectacle is clearly still there for everyone to enjoy. It’s frankly no surprise that to the eyes of many, JJK2 still balances out into a largely successful effort. Awareness of the issues behind the curtain and how those manifest insidiously on-screen shouldn’t make people forget that the result is still pretty damn flashy.

This trend towards an environment where only bruteforced bombast has a chance to thrive, though, actually makes me want to highlight the flashes of subtle greatness that are somehow surviving this collapse. Episode #12 is the debut of the notoriously outspoken and wise Shunsuke Okubo, who acted as first-time storyboarder and episode director, as well as top animation director and key animator. I have the feeling that it will be mostly remembered for Yamazaki’s corrections of Nanami rightfully turning him into the hottest man on planet Earth. What fewer people will remember, and likely fewer noticed in the first place, is how Okubo’s philosophy seeps into the whole episode to make certain appearances—like this climax with Nanami—carry more weight.

Those who follow Okubo’s career know that he inherited the naturalistic, efficient acting of Yuki Hayashi and Soty through his work at Toei. If you follow him more closely on social media, you might also know that he’s a huge fan of the understated fundamentals that the works of Kyoto Animation are built upon, decrying the lack of such a thing in the industry at large. While JJK2 is not in a position to nail those details, as time is tight and all eggs are in the action basket, Okubo’s episode still goes out of its way to emphasize natural, comfortable postures. TV anime is limited in how it places people to the point of being hard to actually parse characters as such, so an episode like this feels like it’s fighting not just trends within this production but for anime at large.

Given how much fighting, assassination, and general chaos has been going on, one of the best showcases of that naturality is… well, people passed out or dead on the floor, always in believable distinct ways. Besides making the characters and world feel more quietly authentic, the benefit of this focused effort also comes through contrast—in a world of natural posture, flamboyant people gain a special type of charisma. Another fan-favorite moment in the episode comes in the form of Meimei’s walk, especially the cut around 35s here; courtesy of a certain uncredited animator you’d expect alongside Okubo. She’s a character who loves performing to an audience, always for a generous fee, and that has never hit as hard than when she’s otherwise surrounded by naturalistic demeanors. Her antics, just like this villain’s, or even Nanami’s moment of coolness, shine brighter because much effort went into an aspect that is invisible to most viewers.

In that sense, the final episode we’ll cover strikes a great balance between tangible, bombastic coolness, and smart craft that one might not notice. JJK2 #13 comes by the hand of Kazuto Arai and Takumi Sunakohara, and can be best described as the spiritual sequel to the second FGO Camelot movie. As we wrote about in our coverage of that film, Arai’s approach to its direction was to disregard production standards in favor of something he described as a more Disney-like approach; which is to say, character-coded animation assignments, with the wrinkle that the people entrusted with one specific character were his close friends, and that rather than simply drawing them, they would effectively have chief director status for their relevant chunks of the movie. One such pal was Sunakohara, and while not without flaw, the resulting work was one for the ages.

How do you follow that up, then? If you read Arai’s lengthy, very interesting summary of how JJK2 #13 came to be, you might think that it’s philosophically quite different from Camelot—after all, we’re going from a movie where individual animators were given freedom on the level of a director, to an episode where adlibs were essentially banned, and the job of an animator often came down to tracing. At the root of both of these, though, there’s a similar idea: the full realization of an artist’s ideas, the same goal Gosso has been chasing all along in his own way. Arai’s first half of the episode, built upon extensive 3D previs and live-action footage he recorded with his friends, and Sunakohara’s second one, relying on his extremely detailed storyboards meant to be layouts already, arrive at it in different ways. Camelot did it by elevating the role of specific animators, while this episode diminishes it somewhat—but it channels their energy towards a goal that everyone should be delighted to contribute to.

What’s that idea, then? It shouldn’t surprise you to hear that this episode draws from Cyberpunk Edgerunners and Kizumonogatari, because Arai already has joked about being ready to be called a ripoff. He pointed at Kai Ikarashi’s episode #06 in the former as the genesis of it all, to the point where he had him help in the planning stages of this episode; Ikarashi was even meant to play a big role in the episode, but in the end couldn’t comply with a schedule that we know isn’t exactly friendly. Just as obvious as Edgerunners’ influence is conveyed through the rim lighting, the brief moments of pause and specifics like the depiction of the rain make Kizumonogatari’s presence equally inescapable. They went as far as mimicking the techniques behind that film, with Sunakohara drawing multi-purpose layers of droplets with incredible adaptability, just like Oishi’s team had done for that movie.

That eclectic mix of influences and non-standard workflows results in an episode that feels unique from the start. For an arc with Shibuya in its title, it’s not until this episode that the action feels physically rooted there; the environments are inseparable from the setpieces, and even its violence is anchored to the real, physical elements that Arai and company filmed themselves around. It’s interesting to see how even its imagery and stylizations are derived from the actual location, starting from the very first shots—coincidentally, also the first of 101 layouts that Arai personally animated. The recurring usage of these signs builds up to Yuji’s fate in this episode, symbolically cut with another diagonal line. Similar things can be said about the direction signs, which are constantly used to represent the turning tides of the battle. Even those external influences are expressed in diegetic ways; the cyberpunk neons only kick in when Choso destroys the regular lights, then proceed to react dynamically to the position and state of decay.

On top of this, it helps that the action storyboarding simply kicks ass, and that the workflow they implemented—for as troublesome as Arai said it was—minimized the room for error in the final stages. A fair number of shots weren’t finished as they were intended to, which you may have noticed through some curious stiffness to certain bodies in an otherwise very kinetic fight, or even a few unreadable closeups that act as patchwork for a complex choreography that was meant to be there. But again, by deliberately keeping the execution so close to what they’d envisioned and personally developed to a large degree, Arai and Sunakohara managed to put together an action spectacle that feels remarkably complete for something that had no business being compressed into these deadlines.

While this is by all means a special episode, that about sums up what Shibuya Incident has been like. A tremendous effort by the staff is making up for a plan that doomed them to failure. After an initial arc that is nearly perfect in execution, the shortcomings here are more noticeable than I’d like them to be, especially in a situation where the team is still delivering occasionally jaw-dropping work. This team deserves nothing but respect, and everyone who put them in this position, right about the opposite.

Though he ultimately framed it as his own responsibility due to his ambition, Arai comically phrased the chronicle of his experiences as “We’re beyond critical, huh? Come at me then, MAPPA!”. And that’s the most positive read you can make out of an otherwise depressing situation: a group of creators rebelling not just against a studio, but every single producer who will wear the success of this show as another badge of honor. As these issues are starting to strongly bleed into the public domain, I hope at least that the person we opened this article with doesn’t end up being right again—the last thing anyone needs is producers drawing the conclusion that planning projects like this is something they can get away with.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, Sakuga Video on Youtube, as well as this Sakuga Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!