Jonathan Clements on some of the battles behind The Wings of Honneamise. Nobody knows who it was who walked into a Tokyo coffee shop, one summer day in 1984, and ordered a mix of Assam and Darjeeling, known in...

Jonathan Clements on some of the battles behind The Wings of Honneamise.

Nobody knows who it was who walked into a Tokyo coffee shop, one summer day in 1984, and ordered a mix of Assam and Darjeeling, known in Japan as a Royal Milk Tea. But there was a cluster of earnest young men at the next table who overheard the words, and one of them suddenly looked up.

Nobody knows who it was who walked into a Tokyo coffee shop, one summer day in 1984, and ordered a mix of Assam and Darjeeling, known in Japan as a Royal Milk Tea. But there was a cluster of earnest young men at the next table who overheard the words, and one of them suddenly looked up.

“Royal Space Force, said the 22-year-old Hiroyuki Yamaga, and his companions nodded and smiled. They had finally come up with a title for their animated film, the first professional venture by Gainax, the company they would set up six months later on Christmas Day. The collective of young fans had previously made a splash with their tongue-in-cheek opening animations for the Daicon science fiction conventions. In a Japan that was scrambling to serve the new market for video cassettes, they had been propelled out of their amateur endeavours and handed the chance to make their own film.

Shigeru Watanabe, then a producer at Bandai, had championed their initial pitch, which contained within it a prolonged meditation on what was wrong with the anime world, in particular the newly stigmatised otaku, and how they planned to fix it:

“If you look at the psychology of anime fans today, they don’t interact with society… Instead they surrender themselves to mecha and cute young girls. However, because these are things that don’t really exist— it just means that there isn’t actually any genuine interaction at work. They get frustrated, and then just go out looking for the next [anime] to give them a hit. If you examine this situation, you’ll see that deep-down, what these people really want is to get along with the real world. And we propose to deliver the kind of project that will encourage them to reconsider the society around them…”

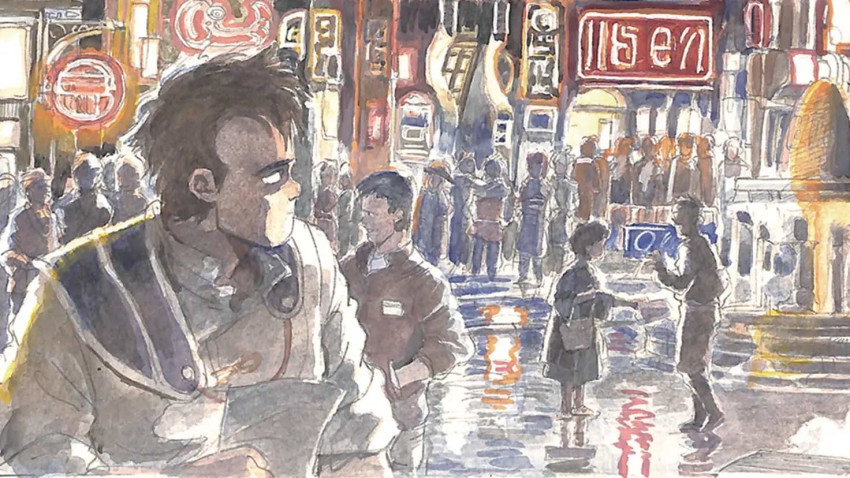

There was a lot more along these lines, along with promises to invest the production with meticulous and intricate world-building. Concept art included in the proposal included 30 water-colour images painted by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto and Mahiro Maeda but, oddly, while there were details of the story, the characters didn’t yet have names.

“I’m not sure what this is all about,” said Bandai’s CEO Makoto Yamashina when Watanabe brought him the proposal, “but that’s exactly why I like it.”

“I’m not sure what this is all about,” said Bandai’s CEO Makoto Yamashina when Watanabe brought him the proposal, “but that’s exactly why I like it.”

Shigeru Watanabe reported in the book Gainax Interviews that animator and designer Hideaki Anno had proudly showed the pilot footage to Hayao Miyazaki, who hated it. Miyazaki told him that on the basis of the material in the trailer, the film would have to be three hours long to cram everything in. While he may well have said that to Anno, his words to Watanabe were somewhat more encouraging, delivering a 50-minute screed about how Anno and his friends were “amateurs,” but that they had a special something and were worth a look.

Miyazaki would later say that the Gainax boys had swindled Bandai, putting together a pilot that was palpably influenced by his own Nausicaä, and then ditching much of the look of the material for something completely different, as soon as they had money in their hands. That’s not how Gainax described it, with Yamaga’s own writings on the subject explaining in great depth how he had spent a year carefully considering and reconsidering how the film should look, stripping away anything that felt too much like it resembled any fore-runners in the field. What this meant, of course, was by the time the time Gainax got to work on their project, the only promise it was still delivering on was the promise to be like nothing else.

Now it was the story of a world identifiably not our own, where a bunch of dead-end civil servants end up shunted into a government boondoggle that is never going to work – the creation of a “space force.” Deciding with a fannish fervour that many critics have identified as an allegory of Gainax themselves, they resolve to take their propaganda exercise counter-intuitively seriously, and to actually try to put a man into space.

That man is destined to be Shirotsugh Lhadatt, played by Leo Morimoto, an actor who had previously provided the voice of Han Solo in the first two Star Wars films. Shirotsugh considers himself to be a failure, having been thwarted from his original hope of being a fighter pilot. Through his relationship with Lequinni (Mitsuki Yayoi), a member of a religious cult, he comes to devote himself to his newfound cause, however unlikely it might seem. His character arc is thus presented as something of a leap of faith – Lequinni’s faith in him, his faith in his colleagues, and his colleagues’ faith in their mission. The ultimate test of faith is presented in the film’s explosive closing act, as the Royal Space Force scramble to launch Shirotsugh into orbit to inspire peace and understanding, even as enemy soldiers are over-running the launch pad.

I asked Hiroyuki Yamaga how it felt on the first day, standing in front of a crowd of expectant animators, all expecting him to tell them what to do. He shrugged and tinkered with his pipe.

I asked Hiroyuki Yamaga how it felt on the first day, standing in front of a crowd of expectant animators, all expecting him to tell them what to do. He shrugged and tinkered with his pipe.

“They’re animators. They’re professionals. It’s their job to do what I tell them. If I don’t like something, I am free to ask for changes. That’s my job. It’s much easier telling professional animators what to do, because they’re being paid to follow my orders. Like waiters,” he added with a cheeky smile, as more wine was put in front of him.

“The most difficult thing is telling amateurs what to do. After you’ve run a fanzine… After you’ve run a convention, when the only staff members are volunteers and everyone is there out of love, and your only means of control is charisma and pleading… After you’ve done that, running a bunch of movie professionals is a piece of cake.”

The film had originally been intended as a relatively low-budget video release, costing 40 million yen, but at the height of Japan’s cash-rich Bubble economy, it accreted a bunch of investors determined to turn it into something bigger. Yamaga would end up in charge of a theatrical film with a soundtrack partly composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto and a budget of 800 million yen, a sum so huge that it would be impossible for it to recoup its costs solely at the box office. It had to sell in other territories; it had to have a long tail on video.

“We were planning on calling it Royal Space Force,” wrote producer Toshio Okada in his memoirs, Testament, “but the sponsors suggested Wings of Lequinni. They didn’t think that Royal Space Force was sexy enough.”

It was Shigeru Watanabe who had to deliver the message, since as the main liaison he was caught in between Gainax and the Bandai money-men. It seems that he told Bandai that Wings of Lequinni would be fine, only for the animators to flip out.

It was Shigeru Watanabe who had to deliver the message, since as the main liaison he was caught in between Gainax and the Bandai money-men. It seems that he told Bandai that Wings of Lequinni would be fine, only for the animators to flip out.

“The moment you call it Wings of Lequinni,” wrote Okada, “the whole story gets skewed. Lequinni becomes the main character and this turns into her story… That’s what the audience would expect. We’d tried so hard to avoid creating any preconceptions, even to the extent of setting it in an entirely fictitious country, but the title itself would make it biased. Our efforts would come to nothing. Most of all, we didn’t want to write about Lequinni, we wanted to write about Shirotsugh.”

The Wings business was leaking into the meetings from All Nippon Airways, the participation of which in the production committee had secured the right for the film to be screened on its aircraft. ANA wanted something with Wings in the title. Other committee members were hoping, rather lamely, for The Something of Something, because they hoped there would be some sort of resonance among the public with the earlier success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. I don’t know what’s worse – the assumption that the public is that stupid, or the possibility that they really might be.

The Gainax creatives were furious with Watanabe, unaware of the brinkmanship he had been forced to get into. Bandai had, in Okada’s words, “got emotional,” and were threatening to take the project away and give it to a more cooperative studio. Since the project had been initiated by Gainax, it was unlikely that would have been legally possible, but rather than back away from an empty threat, producers instead suggested that it would be better all-round if they shut the whole thing down and wrote off the money that had been sunk into it so far. The only thing that stopped them, it turned out, that such a drastic decision would require the firing of a “responsible party,” and the CEO of Bandai had rashly agreed to be the representative manager. If Bandai’s board pulled the plug, they would have to sack their own boss.

Still fearful that the project was spiralling out of control, the money-men tried to reduce it in size. Although they had agreed to a two-hour presentation, they now started arguing that the film needed to come in at 80 minutes, a punchier running time that would allow for two extra screenings a day in cinemas. Okada himself ran the numbers, and conceded that a shorter film, playing over the usual three-week window, could make up to 50% more at the box office.

“But we had written a script for a two-hour film,” he pleaded. “We cut the content as much as we could merely to cram everything into 119 minutes and 58 seconds. By that stage, it was impossible to cut out another 40 minutes.”

In a dramatic confrontation with the board at Bandai, Okada announced that they might as well ask him to cut off his own arm. Years later, he sheepishly confided in his memoirs that he had been cruel to Shigeru Watanabe, his Bandai contact, and that Watanabe was left so exhausted and depressed by the production, that he had returned to his home town, unable to work for a year.

“All creators are children,” wrote Okada. “They want to do whatever they want, and that is how things should be. If something is new and interesting, everybody will profit from their creativity, so they feel, therefore that they are right. And that’s true, everybody will profit in the end. But what about the risks on the way? What about the problems that come up partway through. Someone must take responsibility. That’s a grown-up’s job. Someone has to be the grown-up.”

“All creators are children,” wrote Okada. “They want to do whatever they want, and that is how things should be. If something is new and interesting, everybody will profit from their creativity, so they feel, therefore that they are right. And that’s true, everybody will profit in the end. But what about the risks on the way? What about the problems that come up partway through. Someone must take responsibility. That’s a grown-up’s job. Someone has to be the grown-up.”

I put the idea to Hiroyuki Yamaga but he seemed blissfully unaware of the eye-scratching producer battles outside his studio.

“Oh,” he admitted, “there were the grown-ups, I suppose. The people who had to sign off on everything. The producers who’d put up the money. They left me to it largely, which is why I am still pleased with the film, but every now and then they insisted on some little tweak.”

Toshio Okada himself felt unsuited to the role. A true “grown-up,” he mused would have lied to Gainax’s faces, or come up with some sort of compromise that displeased everybody equally. Instead he stuck to his guns, and the backers backed off. He assumed that he had got what he wanted, but instead, his enemies within the production simply picked a new battleground. If they couldn’t fix the film itself to their liking, they would fix the advertising.

Okada was shocked out of his complacency by the promotional materials, which were assembled by the Tohotowa corporation. In his memoirs, Okada damns the company with faint praise, conceding that they were “really good at selling sequels.” What he meant, it seems, was that he felt they were unprepared to sell anything original, and constantly needed to pretend that something was just like a film that already existed.

“So,” he wrote, “they concentrated on how to make Royal Space Force look like Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which had just been a huge hit.” Someone – it was never revealed precisely who – came up with the odd decision that since Nausicaä had been all about insects, and since there was a young girl in Royal Space Force who had a pet insect, they should draw a giant version of that insect attacking the town.

The first Okada found out about it was when he stumbled across the artist Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, diligently colouring a massive poster depicting a moment that wasn’t in the film, of the pet insect blown up to ludicrous size, stomping on buildings.

“Tohotowa asked us to draw it as test!” pleaded the producer Hiroaki Inoue. “We only have to draw it for them, so they can save face.”

Okada was furious, mainly because Royal Space Force was still in production, and if Sadamoto had been dragged away for three days to draw a poster, that meant three days of vital time he would be unable to put into the film. If Sadamoto had time to spare, he reasoned, he could put it to better use fixing some off-model artwork of Lequinni’s face, which had arrived from an overseas subcontractor. But he could also see what was coming.

“If a picture like this exists,” he said to Inoue, “they will use it, without a doubt.”

With 20/20 hindsight, the film did just fine, released in March 1987 with a title designed to meet all the grown-ups’ demands – The Wings of Honneamise: Royal Space Force. The “Honneamise” part was a sop to Gainax, who refused to give in on the request to make Lequinni’s name part of the title, and instead suggested a made-up word that would ultimately be related to the country in which the film takes place.

With 20/20 hindsight, the film did just fine, released in March 1987 with a title designed to meet all the grown-ups’ demands – The Wings of Honneamise: Royal Space Force. The “Honneamise” part was a sop to Gainax, who refused to give in on the request to make Lequinni’s name part of the title, and instead suggested a made-up word that would ultimately be related to the country in which the film takes place.

“It’s commonly believed that… it was a failure at the box office,” wrote Gainax’s manager Yasuhiro Takeda in his book The Notenki Memoirs. “But that’s completely untrue. It may not have been a huge hit, but it certainly wasn’t a flop.” In fact, Honneamise ran for longer in Japanese theatres than expected – although one wonders how many of the crowds were coming for it or for the film that ran alongside it on a double bill in many provincial theatres – Ewoks: The Battle for Endor. It would also eventually go into profit on a long tail of video sales, although that, too, brought its dangers.

“Producers can work on more than one film at a time,“ wrote Okada. “Directors can own their film even if they are poor for a moment. If a director makes a good film, it will pay off in the future. He might sound arrogant insisting that he’s right, but his reputation will ultimately bear it out. He will get a bigger job.

“So, producers and directors can say ‘It’s okay if we don’t get paid.’ I’ve said that in the past. I’ve done that in the past. But they can only do that because they have savings, or friends who will help out, or something else to lean on. Compare that to the 99.9% of anime staff who are paid a salary. They only get paid for each piece they do, or scene, or day. You can’t ask them to push themselves too far.”

Honneamise might have proved to be a slow-burning success, but the process that brought it to the scene would offer little help in allowing Gainax manage their way through future projects. That, however, is another story…

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History.

The Wings of Honneamise is released in the UK by Anime Limited.