Gridman is a series where creators and fans are not separate entities, but rather intertwined and constantly co-evolving groups. We’re due a retrospective about the production of its latest film Gridman Universe, the franchise altogether, and how the staff...

Gridman is a series where creators and fans are not separate entities, but rather intertwined and constantly co-evolving groups. We’re due a retrospective about the production of its latest film Gridman Universe, the franchise altogether, and how the staff navigated that unique situation.

Why is anime made? Not in general, though that’s a valid question to ask ourselves with such a decrepit industry, but specifically why does an anime get made? Like any other piece of commercial art, you cannot separate financial and creative incentives like they’re completely distinct factors, because in the real world, those are intermingled in more complicated, muddier ways. A dichotomy between passion projects that begin with a creator’s idea and greedy cash-grabs with suits at their genesis would paint a clearer picture, but that simply isn’t the case. There is no getting a production started with producers, and even among them, that figure can range from those who will cynically ride popular trends for profit to the ones who seek ways to fund their friends’ innovative ideas; some of the most popular producers in the current industry, like Kadokawa’s TanakaP, prove that the very same person can shift between those seemingly opposed stances as well. Rather than a binary switch between creative passion and greedy cynicism, reality presents a heterogeneous mixture of motivations that may or may not lean towards one of those extremes.

That said, we just can’t disentangle the figure of the “fan” or “customer” from these projects—something with a more loaded connotation than a mere viewer or reader. Regardless of the specifics about the priorities behind the projects, someone, at some point, has considered that figure of the fan. If it’s an adaptation, it’s a pre-existing group that you might not want to shock with something too dissimilar to what they already love. Even in the case of an original title, there will be proposals as to how to win over as many people as possible through elements that are known to have pleased audiences before. The actual response to those pressures depends on each team, but they always exist. And, when it comes to that relationship between the creators and the figure of the fan, few modern anime are as interesting as the Gridman franchise. Its continued existence has relied on fans to a larger degree than most projects, but the collective that it represents and how to respond to their wishes has drastically changed over the last few years.

It’s far from the first time that we’ve covered Gridman so you’re likely aware of its origins, but it’s worth recapping it from this angle. The series began in 1993 with the broadcast of the live-action tokusatsu series Gridman the Hyper Agent, and then followed up by… some side materials containing ideas for fully-fledged sequels that were never made. Various official publications like Uchuusen Bessatsu: Gridman the Hyper Agent have collected materials about those what-ifs and print-only stories, noting that its toys were actually popular enough for that side of the equation to have spearheaded sequel plans. As to why those would be canceled, the latest revision of Gridman Complete Works cites issues like production costs; which does track with the fact that, as seen in that Bessatsu feature, Tsuburaya themselves also had ideas they wanted to build a new series around. With none of that materializing beyond short magazine serializations, and the entire franchise laying dormant for decades, that once decently sized fandom shrunk to the point where no sane producer would pursue it again for the sake of making money.

Fortunately for Gridman, one of its remaining ardent supporters happened to be Akira Amemiya. Although earlier I said that there’s no dodging the question “How will this make any money?” when making commercial anime, what if one were to use their endless Evangelion riches to allow creators in that space to simply make a short film as they pleased? If a project like studio Khara and Dwango’s Animator Expo were to exist, we could see challenging works of a kind that is rarely funded, personal stories that specific individuals had been ruminating over, and maybe even someone raving about their forgotten toys. Fortunately for us all, Animator Expo does exist, and so does Gridman: boys invent great hero—conceived, directed, and co-animated by Amemiya.

While somewhat cryptic to most people, boys invent great hero is bursting with love for the original series; not only does it feature concepts that would have been adopted in those canceled sequels, but even designs like Gridman Sigma that date further back to scrapped ideas from the TV show. Its existence was thoroughly tied to that figure of the fan, except in that situation, it wasn’t an external factor but the project leader himself. Although it didn’t suddenly turn Gridman into a popular topic, Amemiya had used his love to quietly place the series on the most attentive radars again. As he explained in this Comic Natalie interview, it also helped him make the leap from an animator to a series director; and by that, I mean that it satiated his desire of just drawing the titular hero a lot, since that was his main motivation leading to boys invent great hero. With that out of his system, Amemiya was ready to lead something more ambitious.

As the first question in that interview alludes to, the progression wasn’t quite as linear as you might imagine. Amemiya and eventual line producer Masato Takeuchi—nowadays a freelance director—had already approached Tsuburaya with a proposal to make an Ultraman-related anime; in publications like this roundtable for SSSS.GRIDMAN Super Complete Works, they explained that it was a plan for a skits-based anime inspired by the variety show Ultra Zone, a spirit that in the end manifested in the anime’s many voice dramas. Regardless of the specific vision, though, Tsuburaya refused to lend them such a precious property and instead put lesser IPs at their disposal—with the luck that Amemiya was exactly the right person to offer Gridman to. Since by the time they got that response he was slated to do something for Animator Expo, he gave it a spin and proved his trustworthiness. With that success in his resume, a reputation as a rising figure in a popular anime studio, and reinforced support by the IP owners, the road to SSSS.Gridman becomes clearer.

Those were not all the factors that enabled the project to move forward, however. As has been the norm for every step in this quest across the history of Gridman, fans determined the fate of the project again. A real one, in the person who was going to direct the show, and the vague idea of latenight anime fans as a collective. The truth is that Gridman wasn’t the only tokusatsu series that Tsuburaya had been willing to let them play around with; for all they cared, Amemiya could have chosen to make an Andro Melos series instead for example.

And yet, as he explained in those previous interviews, Amemiya also saw Gridman as an inherently better fit for the tastes of this target audience. He believes that, while many tokusatsu fans watch anime, the same thing isn’t necessarily true the other way around—hence why familiar elements would have to bridge that gap. Gridman always had giant robots as part of its narrative, a staple of anime in his view, which made it more compatible. With the addition of some beautiful girls, a familiar aesthetic for the human side of things put at the forefront, and shifting the priorities of the writing, he believed he had the right recipe to reformulate a series he already liked for a modern anime audience. Whether all those preconceptions hold water or not, they were all made with the idea of appeasing fans, even at a point where those were just hypothetical people.

At the same time, though, it’s important to note that this project has never been one to fully capitulate to outside pressures. An awareness of what fans may be more likely to enjoy doesn’t mean surrendering your vision as creators, as writer Keiichi Hasegawa amusingly exemplifies in the latest film’s Blu-ray booklet. Hasegawa is a renowned writer in the tokusatsu space, to the point that Amemiya couldn’t believe he was allowed to work with him. Despite also having a respectable anime portfolio, he didn’t really have experience leading the writing efforts for regular latenight anime—most of his screenwriting had been under other lead writers and/or on daytime shows—so Amemiya took it upon himself to teach him the (unwritten) rules of latenight anime; including ideas such as not featuring too many adult characters, or not overly-emphasizing romantic elements if that’s not the main premise of the series. Hasegawa nodded along then, but by the time he noticed what they’d been doing around its sequel, they were already infringing absolutely every one of them. As he noted, the result was entertaining, and many people loved it anyway, so no mistake was made.

People did indeed love their work. A franchise that had faded into obscurity became one of the new anime hits of 2018; be it due to the compelling naturalism of the delivery, the love letters to toku and mecha history, the mix of resonant character writing with confident mystery willing to withhold answers, or all of the above, SSSS.Gridman was undoubtedly a success. Those hypothetical fans now existed in mass, and so a story that was written to be self-contained got a sequel approved in the form of SSSS.Dynazenon. A series that only happened because of the (many!) newfound fans, while still pleasing oldheads like Amemiya himself and voice actor Hikaru Midorikawa; rather notably, he was the person who requested the director do something with Dyna Dragon. Perhaps more interestingly, though, this sequel engaged with that fandom on an entirely new level: that of the subversion of expectations.

Dynazenon has much in common with its predecessor when it comes to structure and style, but the choices about what to retain and what to change were an excellent way to keep fans guessing what the hell was going on—not just until the finale, but even beyond it. For as many secrets as SSSS.Gridman had refused to verbalize, the nature of its world and characters were openly dealt with, because there was no completing Akane’s arc without revealing the truth about the fabricated world she escaped into. In contrast to that, Dynazenon lowered its camera to a more human level… while still recording the exact same locations over and over, using them to imply parallels between character arcs across shows, and just adding to the mystique.

Mind you, there’s a more pragmatic but still interesting reason why a choice like that is made. The team behind these works subscribes to the idea that creative choices and specific character writing decisions are often made to conform to production constraints. Amemiya said as much in his interview for Gridman Universe Heroine Archive, when discussing a discarded pitch that we’ll soon talk about; one that would have introduced a character who could bring back kaiju from the TV series, which would have allowed them to reuse assets.

In interviews such as this one held years ago, as well as more current ones that will also become relevant soon, Amemiya has explained the choice to use 3D assets in the first place as a way to emphasize the inhuman, object-like nature of some beings. A compelling idea, though at the same time, also a way to navigate the fact that it has become very hard to sustain a 2D mechanical production. Even writer Hasegawa, in the previous Natalie interview alongside Amemiya, expressed his belief in limitations fueling ingeniousness. After being asked about the rumors that the original Gridman’s computer world setting was determined by the low budget, he took it further and said that the reason why children were the ones helping the titular hero was that they couldn’t afford a proper Defense Team like in Ultraman. And so, by mixing that creatively resourceful mindset with this franchise’s inseparable bond with its fans, we got a sequel that lowered its design costs in a way that kept its fans wondering why its setting was so familiar. An unanswered question, until a sequel movie retroactively did so.

Unlike its unplanned predecessor, Gridman Universe was conceived during the production of Dynazenon; speaking to Febri before its release, Amemiya noted that the reason why he felt comfortable not including Gridman in that second show was that he already had the idea of this crossover in mind. The punchline to all this foresight is that, out of all these entries in the franchise, the one that has given the team the most trouble during the conception stages is precisely Gridman Universe—the one they had actually prepared themselves for. Between all the interviews for Febri—the aforementioned ones on their site as well as those in the Heroine Archive book they published—and those across its lengthy bluray booklet, the core staff have detailed all their struggles to conceptualize this film.

The very first step in its pre-production was a rough plot written by chief producer Yoshiki Usa, also known as the inspiration for the beloved awful mascot Wooser; one that exists (and dies) within this universe too. True to the tradition for this franchise, that rough plot once again emphasized the figure of the fan… meaning that it was nothing but fanservice, which had already been vaguely requested by the committee. With Gridman Universe, Amemiya has been more than ever trying to appease the fandom he created, but he immediately drew a line in the sand. The movie would never coalesce satisfyingly if the characters became puppets to parrot fan-favorite lines and retread completed arcs, if all it did was fulfill preexisting expectations. That rough plot was discarded, and back to the drawing board it was.

Amemiya’s next attempt was to lean on the storytelling format that he had grown comfortable with. Both TV shows had built around female characters whose internal struggles would be projected outwards in literally monstrous forms, so the first tentative plans that stuck around involved the introduction of an original character. That girl, known as Layla or as Mimika in different pitches, would mirror Akane’s original role but from the perspective of someone who isn’t an otaku—thus influencing how she brought forth kaiju into the world. In the first proposal, which began taking form with Hasegawa joining the team again, the story would start closer to where Dynazenon left off. Yomogi’s mother remarried and forced the family to move, prompting him to meet underground idol Layla and triggering Yume’s jealousy over a rival interfering with a now long-distance relationship. Another otherworldly being would manipulate the darkness in Layla’s heart to manifest monsters that Gridman had defeated in the past, as previously alluded to.

In contrast to that Dynazenon focus, the following pitch was more Gridman-centric. Now as Mimika, this original character would be an underclassman crushing on Yuta, whose writing matched the appearance of kaiju in the world. As you can imagine, much of the friction in the narrative would come from her opposing his romantic relationship with Rikka; an idea that was always part of the team’s plans, even in the previous iteration. This idea made it further than any previous one, making it through 3 revisions before animation producer Shunsuke Shida asked Amemiya if he really was fine with it—6 months into pre-production at this point, according to Shida’s own interview in the bluray booklet. Amemiya gave himself some time to think about it, willing to fall back on this idea if nothing better materialized. And by the third week, inspired by the shared belief that the usual structure would be way too cramped within a movie’s runtime, this whole pitch was discarded in favor of what became the movie’s plot. Which is to say: it’s finally time to dive into Gridman Universe!

That rejected original character appears in the background multiple times. Her design is so much more involved than your average mob that they worried it might have been too distracting, but it’s a nice nod to the troublesome planning. Also, she is cute.

That rejected original character appears in the background multiple times. Her design is so much more involved than your average mob that they worried it might have been too distracting, but it’s a nice nod to the troublesome planning. Also, she is cute.

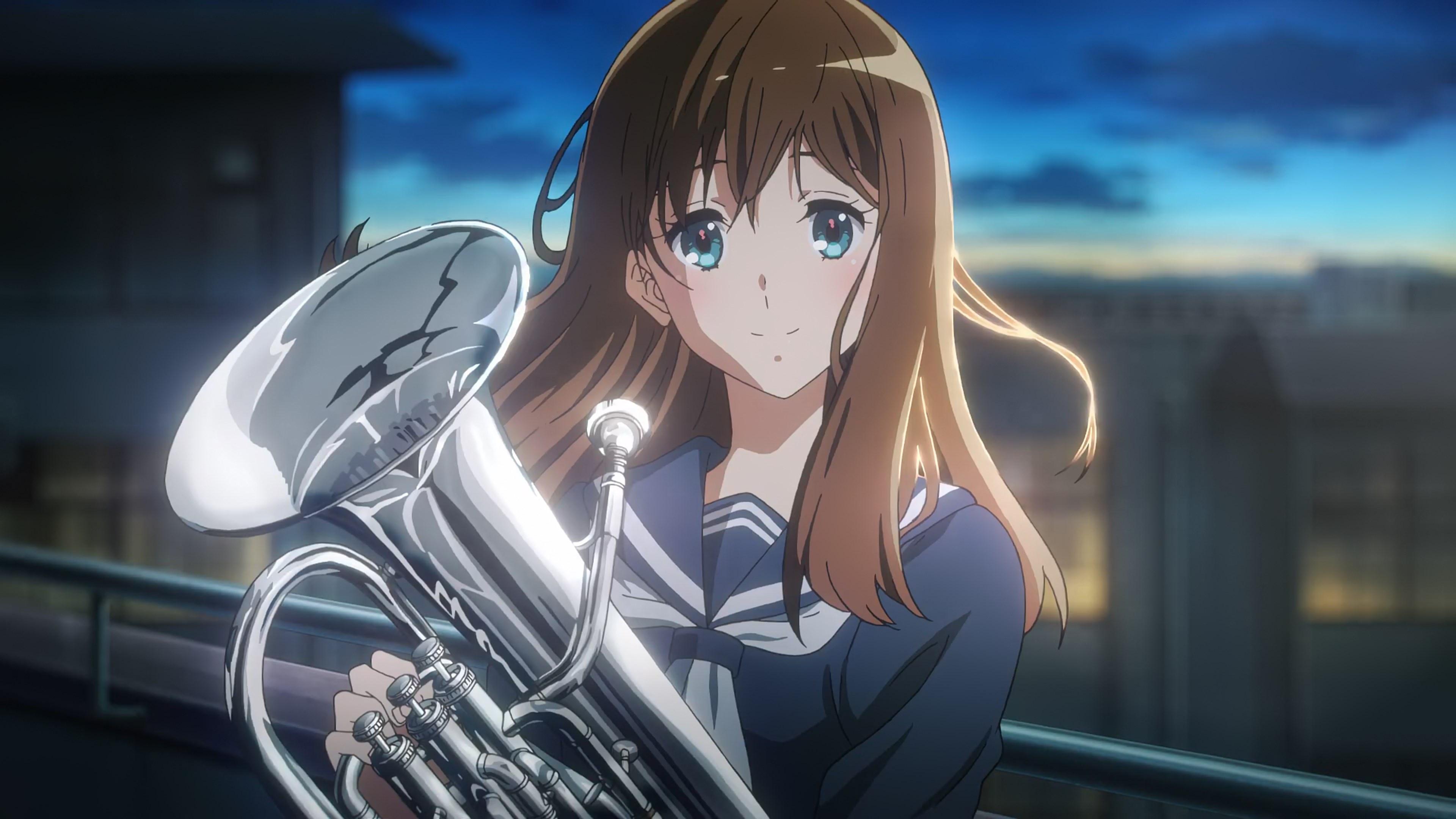

Many things are immediately evident when starting this film. One of them is an even further level of polish and definition to the character art, for a series that was always well put together. In the BD booklet, Amemiya spoke over how nice the schedule had been, which is notable for a series that always stood out positively from that angle. It’s worth remembering that Gridman was wrapped up during the first month of its broadcast, while Dynazenon fared even better as it was finished comfortably ahead of its beginning.

Much of this is owed to qualities of Amemiya we’ve already brought up before, like his ability to sense limitations and write around them, how he surrounds himself with staff that will minimize the need to redo work, and simply a different attitude when compared to other TRIGGER leaders. The contrast with Hiroyuki Imaishi’s chaos and You Yoshinari’s perfectionism, and what that means for their schedules, is so evident that it’s even a topic of jokes on the studio’s Youtube channel. In his BD booklet interview, character designer Masaru Sakamoto jokingly admitted that the only reason he applied for that position—debuting as designer with SSSS.Gridman, hence why he’s so fond of this series—was that the request came from Amemiya, so he felt that it would be more laid back than with other TRIGGER directors.

Since we like to provide a little more nuance than a binary good schedule/bad schedule situation, it’s worth bringing up more details. In the Febri interview leading up to the film’s release, Sakamoto also joked that he was happy it was finally happening, because he’d been working on it until the deadline loomed. This tracks with my experience with other staff members, who also wrapped up later than you might think. At this point, you might be expecting this to make a turn for the negative, but there are nice reasons behind this as well—reasons related to fans yet again.

In his BD interview, photography director Katsunori Shiradou recalls begging studio Graphinica’s management for a position in SSSS.Gridman, as he was a big fan of the original tokusatsu. He became its assistant DoP, attempting to present the series (literally) in its best light. With barely any more experience under his belt, he then took over that leadership position for Dynazenon. Though Shiradou would have loved to reprise the role for Gridman Universe, he readied himself to be replaced when he requested a paternity leave due to his wife’s pregnancy. Given his background, you can easily imagine his delight when TRIGGER folks said they’d adjust the schedule so that he could still handle it. While trying not to sound presumptuous, Shiradou talks about feeling like this film has become like a child of his too, because those two overlapping experiences are inseparable in his mind. A heartwarming series of events that wouldn’t have been possible if management hadn’t been flexible, willing to run later than expected with the risks that implies. Though his is only one of many experiences, it does sum up why this was a project where the staff might want to give it their all.

Another aspect of Gridman Universe’s presentation that quickly stands out is how spacious its layouts tend to be, especially in comparison to the preceding TV shows. One of the defining features of the direction in those shows was the constant reliance on cel-heavy shots that felt deliberately cluttered, lived-in, in a very immersive way. Gridman Universe starts with a shot reminiscent of the first anime series, but quickly you can tell that the camera is stepping back a bit for a wider look at the events. Leaving aside stunning exceptions, that cel component has been lowered significantly, and the movie approaches that idea of immersive layouts from a different angle—a wider one, to be precise.

This switch in the presentation comes across as a better fit for a cinema screen, which is quite funny when you consider that Amemiya has repeatedly said that he didn’t try to adapt too much, and that if anything, he’d rather be making a TV show again because he’s more comfortable with that. It could be an exaggeration on his part, or perhaps a different flavor that comes from other people’s execution of his storyboard; for all that Amemiya said, other directors in the film were delighted because they’d joined the industry precisely to make films, and that sentiment was shared by much of the team as well. The aforementioned Shiradou, for example, pushed for a level of darkness you couldn’t get away with on TV when depicting Yuta and Rikka’s scene at the park, beautifully animated by Kazuki Chiba. Regardless of the reasoning behind it, this is a beautiful film, and one that feels like it adapts to its new screen well enough.

The last point that stands out from the very first scene, and now it’s time to loop back into explaining what Gridman Universe actually is, is that Yuta Hibiki is a huge dork. SSSS.Gridman had presented a heroic but not exactly emotionally complex Yuta, as we inadvertently always saw him merged with an otherworldly being. There was something quite human there—it was Yuta’s body after all, chosen because he was the one person feeling strong emotions for Rikka in a world programmed to love Akane—but what predominated was something that Amemiya is very fond of: the transcendent quality of heroes that protect humanity but exist beyond it. With the titular hero having returned the body to its original owner, though, the staff themselves had to figure out what he was really like. And the answer they arrived at was that the original Yuta is more unhinged; Amemiya’s words, not mine.

Gridman Universe’s premise is stated within the first few seconds. Yuta wants to confess to Rikka, but he has tragically missed the nice groove they had going during the previous series—if they even applies, given that he doesn’t even remember anything and was being essentially piloted by the abstract idea of a hero. Fortunately for him, at least according to an Utsumi he has noticeably grown closer to, a big event suited for a confession is approaching: a school festival. Utsumi and Rikka do have stuff on their plate too, as they’ve been entrusted with writing a play for their class and are now struggling to retell Gridman’s story to classmates with no memory of any of that. In part 1 of the Febri interviews, Amemiya already revealed that the choice of this particular stage and struggle was to ground it in the team’s issues to write this movie’s script. All those discarded pitches may have been a headache, but they found a way to directly incorporate those feelings into Gridman Universe; he believes that just like the characters, they may look like they’re putting a foolish amount of work into something silly, but it’s honest effort they can be proud of.

This new Yuta quickly faces all sorts of distress, from the sightings of Rikka perhaps having an older boyfriend, to the sudden return of kaiju to wreck the world. That is admittedly a lot to suddenly have to process, but his reactions are so all over the place even the director was taken aback. Yuta turns out to be the type of person who magnificently folds at the slightest bump in a relationship, in a way that amusingly contrasts with Dynazenon’s own protagonist; while Yomogi was also quick to cry, the series established him as a very sensible, empathetic boy, whereas Yuta turns out to be a cute crybaby prone to overreaction in any direction. Assistant character designer Mayumi Nakamura, whose first of many roles in the production of this movie was supervising the animation for the introduction and half of the first act, noted that she’d never had such an easy time drawing him. She finds the lack of visual humanization in SSSS.Gridman to be a positive given the context, but since she’s the type of animator who needs to get in a character’s shoes, she struggled with that version a lot more than with this very human Yuta.

What completes this new protagonist is that, just as quickly as he’ll pathetically succumb to negative emotions, he also leaps into danger with less hesitation than he did when he was inhabited by a supernatural hero. The team attempted to bake these qualities into the design itself through subtle adjustments. According to Sakamoto, his posture was slightly adjusted from the somewhat baggy form of the original—he was literally worn there after all—while Amemiya added that always wearing the Accepter instead of the TV show’s wristband symbolizes his inexplicable readiness.

As you’d expect from this franchise, that type of deliberate, dense storytelling extends to the direction as well. Amemiya’s framing is as memorable as it is readable on the surface, rewarding closer inspection and repeated watching as well; any scene you think is loaded with understated meaning eventually turns out to have yet another layer to it that you only catch when rewatching it all. This series has always been fond of repetition to evoke all sorts of feelings, and Gridman Universe is no exception. Familiar framing and poses may make fans smile, especially if it nudges in the direction of a gap they can fill in themselves, but I always find it most interesting when it’s employed for character writing purposes.

The arrival of the first kaiju—and the Neon Genesis Junior High Students with it—offers a great example of that. Yuta dashes away with even less hesitation than when he was fused with Gridman, but turns out that being a regular human being this time around is quite the debuff, so he arrives much more exhausted and takes longer to execute the same actions. This is our new, real Yuta: a brave, perhaps dumb, definitely (but charmingly) pathetic boy. Although it takes the assistance of one unexpected guest, we have to give credit where credit is due—Yuta and Gridman still have what it takes to defeat giant monsters.

Gen Asano’s main role in the movie was for a gattai sequence, his specialty in this series. Since this early part of the film hit the animation stage much earlier while he was available, though, he said he drew a bunch of the battle in the first act—trying to do something fancy to celebrate the theatrical effort. While he didn’t specify how many cuts it was, this is likely his work. We definitely know he handled the following fierce still, because he asked Amemiya why the hell that one shot was on fire.

Gauma, reborn as Dyna Rex after the events of Dynazenon and now part of Neon Genesis Junior High Students, isn’t the only unexpected guest to arrive into this world; and I’m not talking about the kaiju here, since we’ve come to expect those in this series. The mystery intensifies as Yuta appears to be haunted by ghosts, entire dimensions may be colliding, and hey that is the entire Dynazenon cast accidentally walking into a world that looks like theirs, but it isn’t. The world descends into madness, but it does so in such a gradual, peaceful way that it lulls the viewer into a false sense of security—something that Hasegawa wanted to allude to in the script with the recurring mentions of a nice, happy world. Sure, something bizarre is happening, but who is going to worry about Yomogi and Gauma having a touching reunion?

People from different universes are collaborating to make this school festival a success. They’re drawing their own versions of Gridman, a task handled in real life by management staff at the studio. The play’s script appears to be going well, and Rikka doesn’t have a boyfriend after all. Amemiya was strong-armed by members of his own team to add yet another happy event in the form of Gauma reuniting with the princess he loved, though that did trigger his contrarian streak as well. Since people would expect 5000 years’ worth of tragic romance to culminate into a solemn moment, the director decided to do the exact opposite thing. We have these star-crossed lovers from the past, born from an episode in the original tokusatsu and turned into the bittersweet backstory of Dynazenon. A man who was willing to betray his comrades to protect a princess, even though she represented the country that had deemed them too dangerous to continue living. Willing to die poisoned by them, just because he loved her. Their meeting? Just a casual scene where he’s buying groceries.

Dynazenon already had fun by making Gauma always echo a wise saying of the princess, who insisted that the three things one should always protect were promises, love, and… well, they never said the third one. Since this was an opportunity to reveal it, but given that cheekiness of Amemiya, they decided to change the last thing to protect, though doing so in a way that didn’t change the meaning all that much. Now that she’s selling food, the princess says that it’s best-by dates, which is an indirect allusion to the future; something that she did straight up tell Gauma to focus on as well. When covering Dynazenon’s finale on this site, I already speculated that this might have been the final keyword, so now I’ve got even more confidence that it was always the case. Thematically fitting answer, and delivered in the irreverent way that often characterizes this direction and writing duo.

Speaking of I-told-you-sos, the theory I posed to explain Yomogi’s powers and the character dynamics of Dynazenon in that article was that he was the reincarnation of Gauma, while Yume might have been the princess reborn. Their choice of cosplay for their festival might have been an allusion to it, and now that we’re in this world where anything goes, who do Gauma and the princess share those costumes with? I’m just saying, you know.

Speaking of I-told-you-sos, the theory I posed to explain Yomogi’s powers and the character dynamics of Dynazenon in that article was that he was the reincarnation of Gauma, while Yume might have been the princess reborn. Their choice of cosplay for their festival might have been an allusion to it, and now that we’re in this world where anything goes, who do Gauma and the princess share those costumes with? I’m just saying, you know.

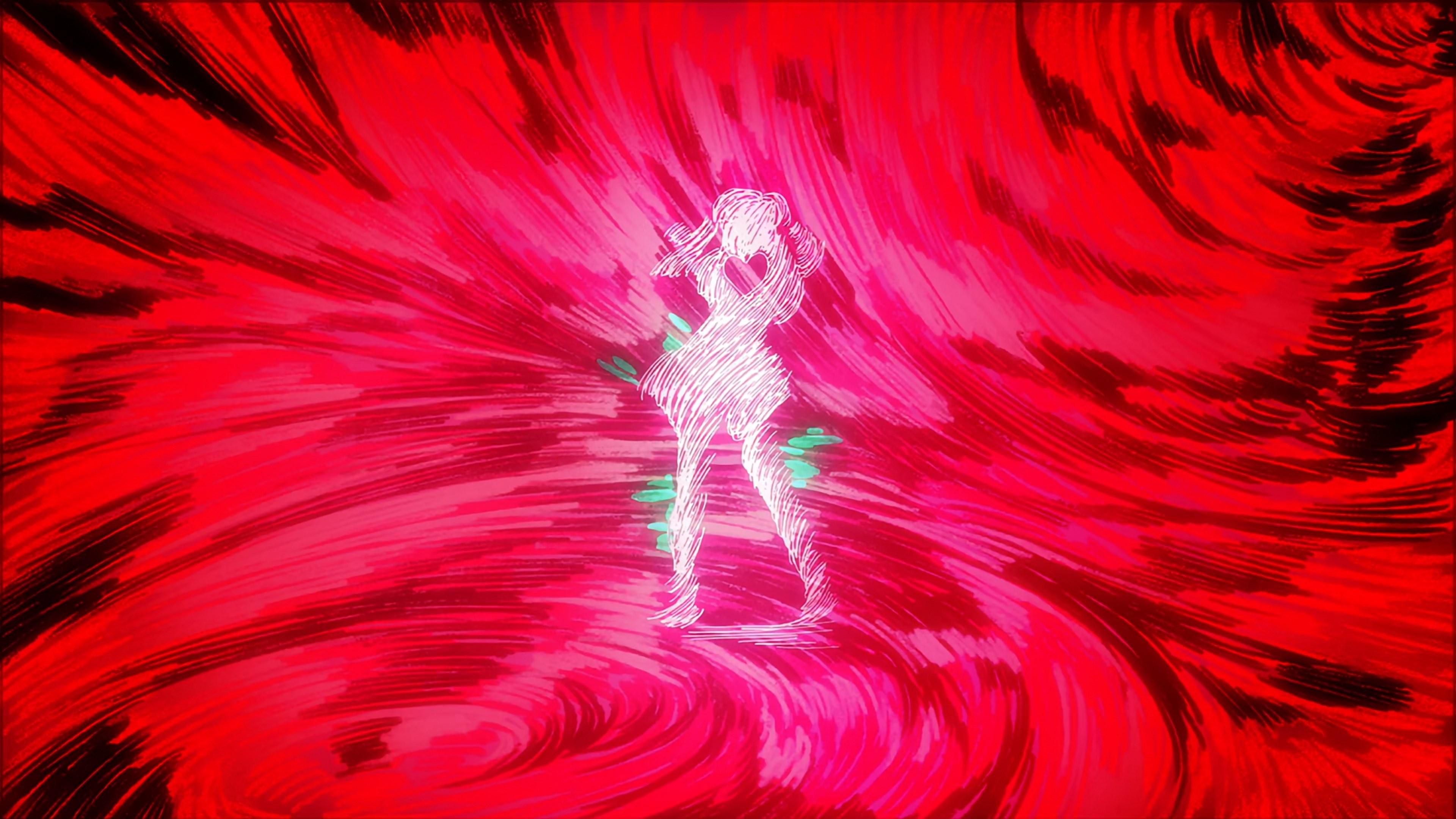

Things are going well. At this point, uncomfortably well. Problems that were a real headache before are now casually shrugged away. Space and time can no longer separate lovers. Exam season has magically vanished. Everyone appears to be relaxed about the universe potentially collapsing, and Rikka doesn’t mind giving up on the version of the script she personally loved. Alexis Kerib is now her cool but slightly embarrassing dad. The world has spiraled out of control and only Yuta seems to be conscious of it, a maddening feeling that no one could have conveyed better than Kai Ikarashi. Hasegawa noted that Yuta’s realization that something is fundamentally off played out differently in the script, but even when he’s only acting as a key animator, Ikarashi is the type of artist you’d better allow to reinterpret a scene. One of the smartest choices made in the two preceding shows was to fully entrust him with episodes set in the world of dreams, befitting his radically different style. Given the inherent chaos of his art, having him animate the realization that the universe is falling apart might be an even better fit.

After that existential crisis makes Yuta fall off the stairs, another realization hits him: that didn’t hurt at all! In Gridman fashion, this much had already been since the beginning of the movie, when he was more confused than pained over a ball smashing his face; Hasegawa’s delightful screenwriting makes it so that Yuta denying that he’s in pain feels like a kid trying to look tough in front of his crush, while already building up to this reveal. Right as he—and his protagonist role buddy Yomogi—are reaching an understanding of what is actually going on, we’re interrupted by more exciting action. Not only have more kaiju arrived, but so have Knight, 2nd, and even Goldburn. The movie states that it’s going to capitalize on the premise of a crossover movie with a cool shot of allies readying up for the action, but it doesn’t show its hand until they’ve earned a hard-fought win. Suddenly, Kaiser Gridnight is backstabbed by Anti’s original self, causing Gridman as well as most Dynazenon characters to vanish. So, what is exactly going on?

This is indeed Anti and Anosillus from SSSS.Gridman, ready to reveal the truth not only about this movie but also the prior series. While everyone had assumed that Knight and the older 2nd were these same characters after some years had passed, the truth is that they’re different beings; something they foreshadowed at the end of SSSS.Gridman, as Calibur said Anti would remain in that world and thus couldn’t really be the Knight we see crossing dimensions in Dynazenon. Why are they so similar, then? For the same reason why the setting of the two shows is nearly identical: Dynazenon was one of many realities created by Gridman itself, in the image of its adventures in that first season. This is one heavy reveal that the team was hesitant about—would that fandom that is so deeply tied to the series itself accept that the previous series was on some level, fake? Ultimately, my reaction was the same as the unperturbed SSSS.Gridman folks. They too were a fabrication, and yet their entire show vindicated their existence and bonds as meaningful, so who cares if Dynazenon’s world was artificially conceived too? If YomoYume didn’t exist, I might have invented it myself.

If that choice brought some hesitation to the team, the reason why this whole situation happened was even more controversial. Amemiya has been very honest about his decision-making for this movie, openly pointing out things that he wouldn’t have done if it were all up to him, or those that he doesn’t like; it’s not common to hear a director say that he’s not a fan of movies after their theatrical debut, but that’s the level of transparency he has kept for all interviews. It should be clear at this point that much of this production process has been a challenge to navigate between expectations—of fans as an external element, but also the diverse voices in the team as fans in their own right—and his convictions as the project leader.

It all started with him ditching a rough plot because it was mindless fanservice, but at the same time, no one is more aware than him that it has been a fan-fueled miracle to get Gridman this far. Some smaller concessions have been made with that in mind, but in this case, it’s more about having to go against himself as a fan for the sake of the narrative. As I brought up earlier, Amemiya loves the transcendent nature of heroes like Gridman, existing beyond puny humans and their feelings. And yet, the way to make this all click was to allow him to have been dyed with that humanity, subconsciously causing him to crave more adventures and comradery like those of SSSS.Gridman. Just like it happened to a certain girl in the first TV anime, a supernatural being then used that as an exploit for their evils—hence why the universe is currently a Gridman-shaped mess.

The situation is clearer by this point, but that doesn’t make the problem easier to solve. And that means it’s time for Amemiya to push another button he has always hesitated to press; and no, it’s not one to summon the actor who played Gridman the Hyper Agent’s protagonist to give Yuta a ride, though he’s always welcome too. When you pretty much need a deus ex machina to solve a dimensional mess, it’s quite handy to have a literal goddess who has been enjoying her retirement since the end of SSSS.Gridman. At the time, Amemiya thought that he’d never bring her back because that arc had beautifully wrapped up, but now found himself in a position where everyone in the audience expected her, and the story needed a special character.

If he was going to do it, though, it needed to be grand. And grand it is. The person who helps Yuta in his metaphysical quest to save Gridman and the entire universe is none other than Shinjo Akane; not the capricious goddess we saw at the start of SSSS.Gridman, but a bettered human who just wants to help her friends. And by human, I mean literally so. Just like in the epilogue for that show, we see a live-action rendition of Akane. One who has made some friends, become more proactive, and even tamed Alexis ever since then. One who is ready to kick ass in her flashy new outfit, because the team also felt like Akane’s reappearance demanded to match the narrative impact with equal visual flair.

Sakamoto is a big fan of his senior sushio, so when he found out he was going to animate his new design for Akane as she transformed, he was really giddy. When he saw the sequence, though, he realized that sushio had completely transformed the design into his own. Sakamoto respects him too much to feel comfortable correcting him, so he waited until another vet (and good friend of sushio) like kojipero corrected parts of it before doing his own redraws.

The last stretch of Gridman Universe is nothing but chaotic euphoria. Everyone gets a new transformation, yet another combination, a powerup never seen before, and Yume reappears to get her wifehusband back. Logic is gloriously thrown out the window as one theme song connects to the other. Even people in the team admit that it becomes hard to remember who is fused with whom at points in this fight, which might actually delight the fans of the genre. If there was a form of fanservice the movie deserved, it was this. In the end, Gridman owns up to its individual weakness, which Amemiya believes is part of the hero’s unique charm. On its own, it couldn’t even manifest into the world. But thanks to a bunch of kids in the first tokusatsu series, or a large collection of allies in this movie, there’s no one Gridman can’t defeat.

After such a bombastic win, the final act is a peaceful victory lap. Anti gets to thank Akane for everything, and she physically reciprocates. I think it’s important to note that, in a movie that I know some people won’t watch because of the romantic premise with Yuta and Rikka, the latter’s relationship with Akane is always treasured. Since the start of the movie, Rikka makes it clear that the part of the Gridman’s story she really wanted to tell was Akane’s. Even in her first meeting with Yuta in the movie, Amemiya revealed that her subtle arm movement was just to showcase the purple props that represent Akane, whom she keeps close to her heart before she has come to terms with how she may feel about Yuta. Their last interaction, which also doesn’t need words, is a direct callback to their tender relationship as we saw it in SSSS.Gridman’s ending sequence. From its own angle, the movie definitely does their bond justice.

Mind you, I wouldn’t pressure anyone who was put off by the premise into watching it. Though there were indeed elements in the narrative that always pushed Rikka and Yuta together, hence why the staff called this relationship unfinished business, it wasn’t brought into the emotional forefront in the way that Akane’s and Rikka’s relationship was; for starters, because Yuta didn’t even get to be a person in that show. For as much as this movie epitomizes the idea of By fans and for fans, those aren’t a monolithic group. The two girls’ relationship resonated with a lot of people, myself included, and no metaphysical complications were going to stop people from reading it romantically—in fact, that just makes it more appealing sometimes.

I think Gridman Universe is a great movie, but I’ve got friends who I know would weep at the same LGBT awareness poster sneaking added into the dream where Akane was trying to seduce Rikka now being the background of Yuta’s romantic pursuit. Amemiya concluded his Heroine Archive interview by calling this movie a beautiful superfluous addition, and that is what it reads like to me as well. It’s a film that constantly screams that it’s fine for everyone to have their own Gridman, and if yours doesn’t include this movie, that’s perfectly alright too.

At one point, Amemiya actually intended for the final 30 minutes to be shot as a live-action movie. Though that might have been cool, the gang found out how much work even just a few scenes can be; they had to change their plans about filming at dawn or in the evenening for scheduling purposes, and when they went to pray that the day of recording they’d settled on was sunny, they were met with rain on that same moment.

At one point, Amemiya actually intended for the final 30 minutes to be shot as a live-action movie. Though that might have been cool, the gang found out how much work even just a few scenes can be; they had to change their plans about filming at dawn or in the evenening for scheduling purposes, and when they went to pray that the day of recording they’d settled on was sunny, they were met with rain on that same moment.

Speaking of romance, there’s only one thing left for Yuta to do. After many cute goodbyes, including YomoYume flexing their essentially married status—maybe we can remove the adverb given that he casually proposes as they fly away—it’s finally time for the protagonist to do the deed. Although Amemiya had storyboarded almost the entire film, with the only exception of the ultimate gattai that Asano himself boarded, this final act was handed to the aforementioned Mayumi Nakamura instead. Though she’s never drawn storyboards for an actual episode, let alone a movie, she found herself doing it because of a director who really trusts her… and who didn’t want the challenge of handling a confession, as he admitted.

In the end, Amemiya didn’t abandon her, since he acted as the unit director for these final scenes as well; placing her in the curious position where her first narrative storyboards were being executed by the person leading the project, who asked her if he was interpreting everything right. Though he adjusted some mannerisms, mostly to make the two kids appear cuter as the confession does indeed work out, about 80% of the sequence remained as she’d envisioned. And, given that she also key animated the confession itself, that’s a whole lot of responsibility for someone whose career keeps leveling up alongside this particular series. Her BD interview makes it clear how much she treasures Gridman, which she’s as much of a fan of as every viewer who has made all these titles possible.

At face value, that is a perfectly ordinary story. The continued existence of a franchise is going to have to rely on the support (and monetization) of fans. But when it comes to Gridman, the collective represented by that word has drastically changed, and the way that its creators have engaged with them has shaped the series into something fascinating. Amemiya has concluded many of these interviews we’ve been returning to by saying that he’ll return to this series if possible, but for now, he’d love for someone else to offer their own take on Gridman—that way, he’ll be able to concentrate on being a fan again, which is just as valuable of a position.

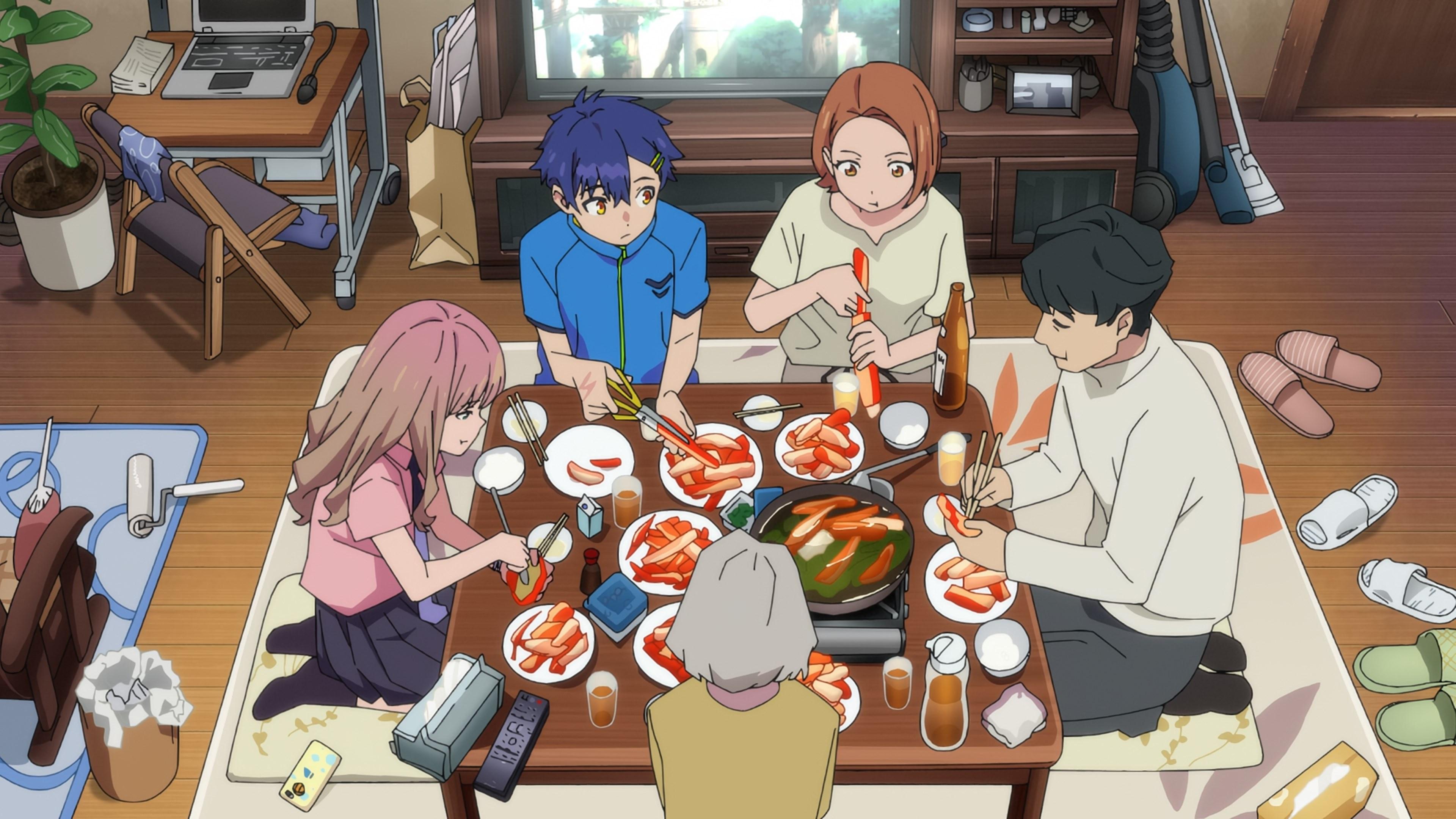

Studio TRIGGER tradition to tease their next work is respected with various sightings of Dungeon Meshi, most notably as the PV plays in the background of the aftercredits scene. Can you believe the crab kinda sucked though, after all that?

Studio TRIGGER tradition to tease their next work is respected with various sightings of Dungeon Meshi, most notably as the PV plays in the background of the aftercredits scene. Can you believe the crab kinda sucked though, after all that?

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, Sakuga Video on Youtube, as well as this Sakuga Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!