By Helen McCarthy. None of us believed that the ostentatiously non-marketed event known as “the last Hayao Miyazaki film” was actually the last Hayao Miyazaki film, and we were right. On the red carpet before the international premiere at...

By Helen McCarthy.

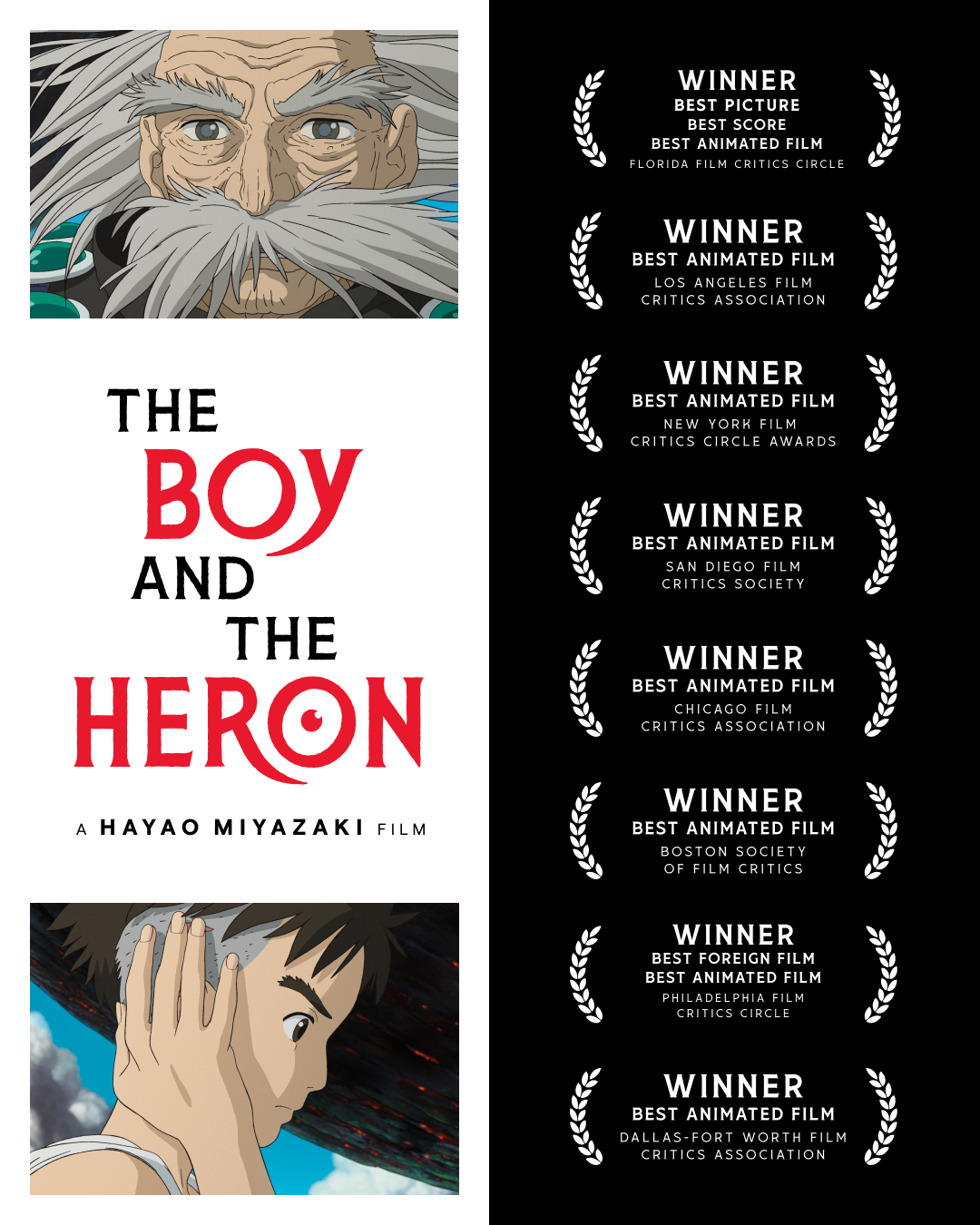

None of us believed that the ostentatiously non-marketed event known as “the last Hayao Miyazaki film” was actually the last Hayao Miyazaki film, and we were right. On the red carpet before the international premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, Studio Ghibli Vice-President Junichi Nishioka told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation that Miyazaki was in the office every day working on ideas for his next movie. Speaking to the French journal Libération a couple of months later, Miyazaki’s friend and producer Toshio Suzuki said that he had already forgotten has last work and thinks about his new project every day. “In life, there’s only work that enchants him.”

And yet, when a film-maker is 83 years old, there must be a reckoning – not only with past and present, but with time and capacity. It took Miyazaki seven years to make Kimitachi wa do ikiru ka (How do you live?) the film released overseas as The Boy and the Heron: two years in pre-production and five in production. According to Suzuki, on The Wind Rises the studio could produce ten minutes of animation in a month, but on The Boy and the Heron Miyazaki’s advancing age slowed the pace to one minute of animation a month. Left in his complete control, a 124-minute film would have required over ten years in production. The practices of a lifetime had to change. And so they did.The lifelong Miyazaki habit of personally checking and correcting every shot came to an end, with many passed over to the animation director, Takeshi Honda, for revision. He has relaxed control to a remarkable degree, focussing his attention on the area where only he can work as he requires: on the story. In terms of the animation, Honda seems to have achieved a wonderful balance between Miyazaki’s looser, more rounded style – a style that stems partly from his mentor Yasuo Otsuka’s belief that animation should edit reality in the service of the story – and a greater concern with realism.

The story is unrelated to the Japanese novel whose title it borrows, although the book itself makes a touching cameo appearance. Its literary roots lie more with the 1936 Edogawa Ranpo novel The Ghost Tower. Miyazaki loved that book, to the extent of providing artwork and comic pages for an illustrated edition in 2015. The mysterious tower that dominates the second half of his film functions as both a magical gateway and a symbol of the very literal alien influences acting on Japan in the 1930s and 1940s, transforming its culture in strange and not always predictable ways.

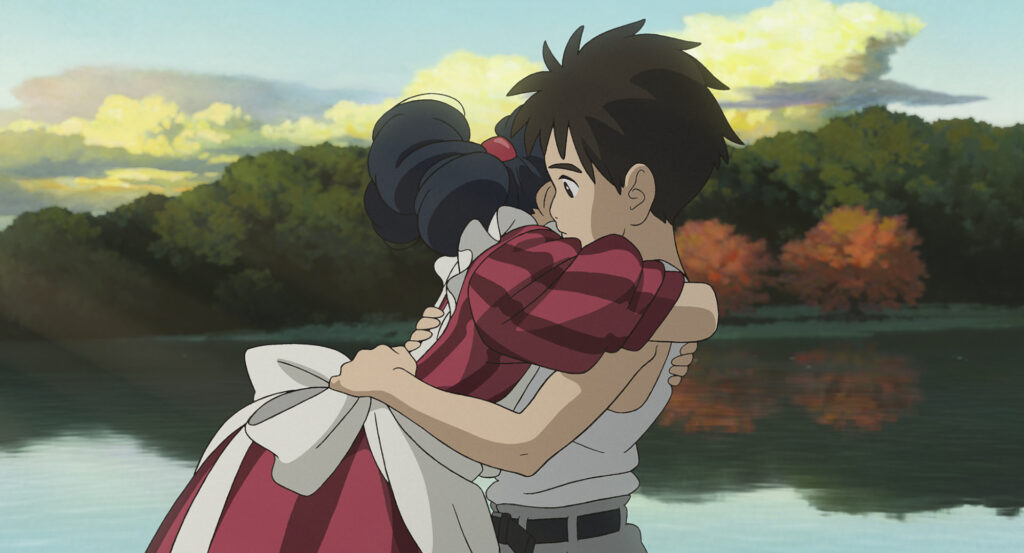

But the real core of the story is a boy not unlike Miyazaki himself – or his late friend Isao Takahata, who was five years older and gave his own account of dodging burning debris through firebombed streets during the Pacific War. Mahito loses his mother in firebombed Tokyo, and believes that she is calling to him from beyond death to save her. He is deep-frozen in grief when his father marries her younger sister.

Father and son move out of an increasingly devastated city to the relative safety and comfort of the countryside. The sisters’ ancestral estate borders the modern factory where Mahito’s father owns a company making cockpit canopies for Japan’s fighter planes. Like the young Hayao Miyazaki, Mahito’s safety and affluence is a direct result of privilege, and he resents the father he sees as brash and entitled. Struggling with change he cannot control and grief he cannot forget, forcibly relocated to a strange environment, surrounded by weird creatures with disturbing habits and old biddies who fuss over him nonstop, Mahito must also come to terms with the fact that his mother’s replacement is pregnant.

Lured by a talking heron who appears more and more gross and deceitful the more he becomes anthropomorphic, Mahito finds a crumbling tower, seemingly lifted from a European fairytale. One of the old housemaids tells him that only the bloodline of the ancestor who built it has access to its mysteries and magics. But privilege alone will not save him. Until he begins to understand that he relies utterly on the people around him, to see the true selves under the shapes they wear, he cannot save anyone, even himself. And when he is finally offered the opportunity to inherit the powers of the mysterious tower, the choice he makes defines him, as it defined his ancestor.

The pacing of the film is so chaotic that at times it resembles a dream state, where the doors of perception are open but the ability to control what flows through them is largely absent. To me that didn’t matter, because the pacing keeps faith with Mahito’s internal struggles. Yet it appears at times that we’re watching an anthology film, a showcase for the talents of Miyazaki’s most trusted colleagues and those whose work he truly admires. The control freak who pushed both Sunao Katabuchi and Mamoru Hosoda off the Ghibli director’s chair has always had huge admiration for craft skills, for the ability to create superlative animation in the service of his story. He’s sought out the best of the best – including Honda as animation director – and trusted Honda to bring in staff with those skills, including former Kiki’s Delivery Service animator Toshiyuki Inoue, alongside Ghibli veterans such as Shinya Ohira and Masaaki Endo. His longtime collaborator Jo Hisaishi provides a luminous score.

The result is ultimately life-affirming, although not entirely joyous. Despite the proliferation and variety of imaginative and visual marvels in the film (I am still boggling at the militarised parakeets who are also dedicated gourmands, and the adorably marketable kodama-substitutes whose true purpose spans realities) this is a film about owning and paying debts: debts of privilege, debts of kindness, debts of community, debts of survival. Fleeting references acknowledge Miyazaki’s and Ghibli’s films and influences, nod to figures in the director’s life, reflect on past mistakes, and pass by as swiftly as grains of sand through an hourglass or days on an old man’s calendar. The past is the past, the film seemed determined to tell me. It was sometimes lovely and sometimes terrible, but I don’t live there anymore.

And so Hayao Miyazaki has made another film, and surprised me in two ways: first, by surrendering some of his renowned iron control over the processes of animation production that have intrigued, fascinated and infuriated him for sixty years; and second, by making a film that moved me as no other. Miyazaki film has moved me since Princess Mononoke. When I saw that in 1997, I had the sense of an ending, of a storyteller consciously closing the book on one cycle and moving on to another. I have that same sense now. It’s not the sense of someone closing the book on his career. It’s the sense of someone settling accounts as best he can, coming to terms with reality, and getting ready to tell another story in whatever ways remain open to him.

Helen McCarthy is the author of Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation. The Boy and the Heron is released in UK cinemas in December.