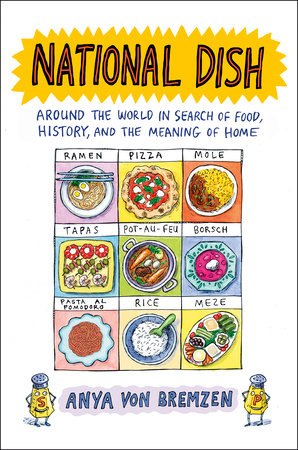

Anya von Bremzen. National Dish: Around the World in Search of Food, History, and the Meaning of Home. New York: … More

Anya von Bremzen. National Dish: Around the World in Search of Food, History, and the Meaning of Home. New York: Penguin Press. 2023. ISBN: 9780735223165. pp. 340.

Richard Zimmer (Sonoma State University)

Anya von Bremzen is one of the world’s great food writers. In National Dish he has prepared a whole feast for the reader. It is part a history of how many countries came to create a specific dish or series of dishes that symbolize that country. It is part her personal journey about learning about that development. And it is part her conversations with chefs and food writers about the whole process. It is a treasure trove of information for anthropologists, food historians, food critics, and “foodies” everywhere.

She begins our repast with a discussion of what has become the “national” dish of France—pot au feu. Careme, the leading French chef of the early Nineteenth Century, positioned it as the essential French national dish. She sees the mélange as having a “…monumental weight in French culture” (8). For Europe, the French set the words and terms of the discussion not only of a national dish but the whole kitchen battery, such as “chef” and “gastronomy” (6). France held on to the iconology of this particular dish and its general superiority until the challenge of the cuisines of immigrants and foreigners came to the country. She cites Benedict Beauge, the gastronomic historian: ”…only Japanese chefs seem fascinated with Frenchness, while Tunisian bakers were winning the Best Baguette competitions“ (9). Then the immigrants bring their specialties from their homelands, creating an internationalization of foods in places which may still hold onto their national dish.

In Naples, von Bremzen reviews the history of the development of specific Italian food, particularly pizza and pasta. She not only sets that history in terms of existing writing, but she also sets it in the voices of people in the street, contemporary practitioners, and researchers, including anthropologists. This material is invaluable for the novice reader and the professional. What she sketches is a picture of a Neapolitan cuisine shaped by poverty, snubbed by the higher classes, disparaged by Northern Italians. It is then “exported” to the New World, along with the large exodus of Southern Italians and Sicilians to the United States, Argentina, and Brazil. Using the US as one focus, the exodus created an Italian American cuisine, borrowing from and differing from Neapolitan cuisine. Still later, Neapolitan cuisine continued to spread again, influencing its progeny. And, in true anthropological fashion: “I recalled Marino the anthropologist describing this Neapolitan syndrome. Self-mythologization” (75).

In Tokyo, she paints a picture of the role of ramen and rice and contemporary food in present day Japan. This role is complex because of Japanese history both dishes are national and international. Von Bremzen visits a traditional school for preparing sushi and sashimi, noting that only those people who can afford the time can take these classes. She recounts that for most of Japanese history, barley and beans were the staples—not rice. Rice, (meaning white rice, ) became the mythologically based food during the Meiji period as a way of reinventing Japanese identity. Earlier, she recounts the ways in which meat and Shintoism replaced vegetarianism and Buddhism as a response to Western colonialism. She talks about how ramen, like pizza, first became the food of the poor, especially in the Twentieth Century, and now the food of experimentation and commercialism, a brand for the new urban elites, both native and foreign. And she then stops at a Family Mart, a convenience store, where “…a pizza-man, a steamed Chinese bun with cheesy tomatoey filling) and diaphanous raspberry-flavored “Fami-macaron” [sell] for just 12.5 yen” (100).

Starting in the 1940’s, she recounts, ramen became the national dish and the symbol of a national dish, Japanese food-eating habits and causing a world-wide revolution in fast-food. Von Bremzen then adds first-person accounts of the history of ramen’s success by her conversations with the family who make most ramen noodles in the country.

So, is there a Japanese national dish? Has rice been replaced? Has ramen taken over everything? Von Bremzen paints a larger picture. Yes, there is internationalization of Japanese foods. And there is an explosive growth of the national food institution—the kobini. The kobini is the homegrown version of the convenience store. It continues to cook up new food offerings all the time, expanding its market to people who previously looked down on it. The kobini is a point of social contact and a social service agency—staff trained to recognize and address dementia in an aging population. The Japanese national food is whatever the convenience store keeps developing, including affecting the very structure of the Japanese language (128-131).

Then Seville. Are tapas the national dish? Von Bremzen serves this as the first entrée, setting them in the lively atmosphere of this Andalusian city. She tempts with the variety of hams, seafoods, and other delectables and puts the reader in the pleasurable languor of southern Spanish life. But tapas is a relatively recent branding of a national dish. Before that, there was paella—under the Franco regime. The creation of a national food, whether tapas or paella, became the creation of a mythical national identity which rescued the Spanish economy after the Spanish Civil War as a tourist destination (141-143).

She sets tapas and other Andalusian specialties in the context of the cultural life of Seville. Seville was the initial port from which European colonization and commerce flowed. It stayed so until the Guadalqivir River silted up many centuries ago. Eating life, communal life, developed in a more casual and enjoyable pace. Where Tokyo “required” old people to meet at convenience stores and New York required appointments to socialize, Seville was casual and enjoyable (149 et seq.). Von Bremzen then takes the reader on a tour worthy of Hemingway and Cervantes, mixing all Spanish history, with its roots in Jewish and Muslim cooking, such as the potaje (stew) through its present. The whole chapter is filled not just with history but with conversations with the people involved in the culinary and cultural life of Andalusia “…where the magical and matter-of-fact share the road” (185).

Then von Bremzen travels to Oaxaca. She paints it as the place most culturally diverse, most Indigenous in Mexico. Oaxaca has its home-grown diversity, its Spanish heritage, its mestizo character, and its modernistic qualities. She sets her discussion around the large number of moles in the diversity of the region’s agriculture. She describes one of her interviewees talking about her ethnic mixedness, her mestizaje, in terms of roots and modernism: “Eating both bread [a food and symbol of colonialism and modernity] and tortillas [a food of Indigeneity, of the colonized] seemed to her like a great privilege of her mestizo identity” (197). But mestizaje can also be seen as excluding the Indigenous population of Mexico as well, as von Bremzen notes in her review of work on the topic by anthropologists, historians, and other thinkers (199-200). Should mole be the national food? Or just one of them since it is a complicated issue with origins and practices in pre-Hispanic Mexico, Colonial Mexico and contemporary Mexico?

And what about tortillas? Is that the “national dish”? von Bremzen provides an excellent short history and a first-hand account of producers of tortillas, previously and currently. Corn was first developed as a useful food in Mexico and is now the largest staple crop in the world. People made their corn into tortillas by hand. It is now a machine-made product, and yet there are still local growers and people who make better tasting ones by hand (204-207). (BTW, tortillas have gone international, as, for example a Persian dish—Reference 1.) Included in this discussion is a choice ethnographic morsel—a visit to the Oaxacan family producing tortillas. Von Bremzen paints a picture of incredibly hard-working people earning little, furious at the bland tortilla monopoly Maseca and quite conversant with current gourmet and natural food trends (211-214). Also wrapped up in their lives is a portrayal of the way in which Indigeneity, feminism, and Mexican politics work together. The question is continuously raised: is making tortillas by hand by women a task of pride or enslavement (221 et seq.).

As a final dish , von Bremzen tells a story of her meeting with a famous “cultural treasure”—Dona Abigail—visited by the likes of Anthony Bourdain. Dona Abigail provides her with a wonderful recipe for chocolate-atole for her wedding (236 et seq.).

Istanbul—the last stop on this journey. Von Bremzen reviews the national dish/political influence quandary in present day Turkey. A great variety of “Turkish” foods spread throughout the areas of Eastern and Southern Europe and in the Middle East, the Caucasus, and Russia during the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman empires. Even with the nationalism of Ataturk, Turkey, shrunken after WWI, was still cosmopolitan and diverse. Migrants from Anatolia came in, bringing in their foodstuffs—including shish kebab and hummus. Then President Erdogan, focusing on a national, religiously Moslem identity, promoted a “purer” identity—more specific “Turkish” foods without alcohol. “His” foods were more plain, more representative of the poor. And those foods are in sharp contrast to the past rich diversity of Turkiye, of the Rum—the Greeks who have remained in the country, and the dishes of the various groups—Jews, Armenians, Kurds, to mention but a few of the Ottoman Empire. In a glorious tour de force recounting of a potluck dinner, van Bremzen recounts the ebbs and flows of the different dishes, the different histories, the ways politics influences the meal, the players and the sources, the researchers and the chefs, the cosmopolitanism, the simplification “…all mixed up…the quest to assign ur-identities to particular identities and disentangle their complicated entwinings seemed like sheer absurdity” (291).

Von Bremzen makes borsch [Russian Anglicized spelling] or borscht [Yiddish Anglicized spelling] her last serving. Is it Ukrainian? Soviet? Russian? A dish of any of the many former Soviet nationalities? Like hummus in the Middle East, can its provenance be separated from politics? Is the UNESCO of borsch as Ukrainian (303) sufficient to overcome the horrors of the politics of the present (2023) military engagement and the claims of the Russians? And which and whose borsch is it? There are so many (308-310).

This delightful and powerful book is useful for all levels of students in anthropology, sociology, history, culinary studies, and gender studies. It provides not only rich historical background but first-person accounts of and by people engaged in the decisions to create national dishes. Its bibliography is comprehensive and extremely useful. It adds to the growing literature of the history and politics of creating “National Dishes” (see Reference 2.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Reference 1

(Accessed Oct. 20, 2023)

Reference 2

https://www.listchallenges.com/list-of-national-dishes-around-the-world

(Accessed Oct. 20, 2023)