Human Expansion and its Impact on Megafauna Populations

Human history is a tale of migration and adaptation. About 100,000 years ago, the first modern humans ventured out of Africa in significant numbers, demonstrating remarkable adaptability across a diverse range of habitats worldwide—from deserts and jungles to the frigid landscapes of the far north.

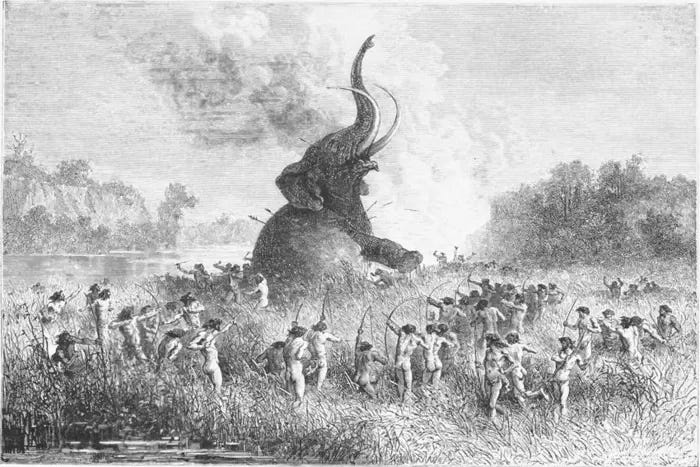

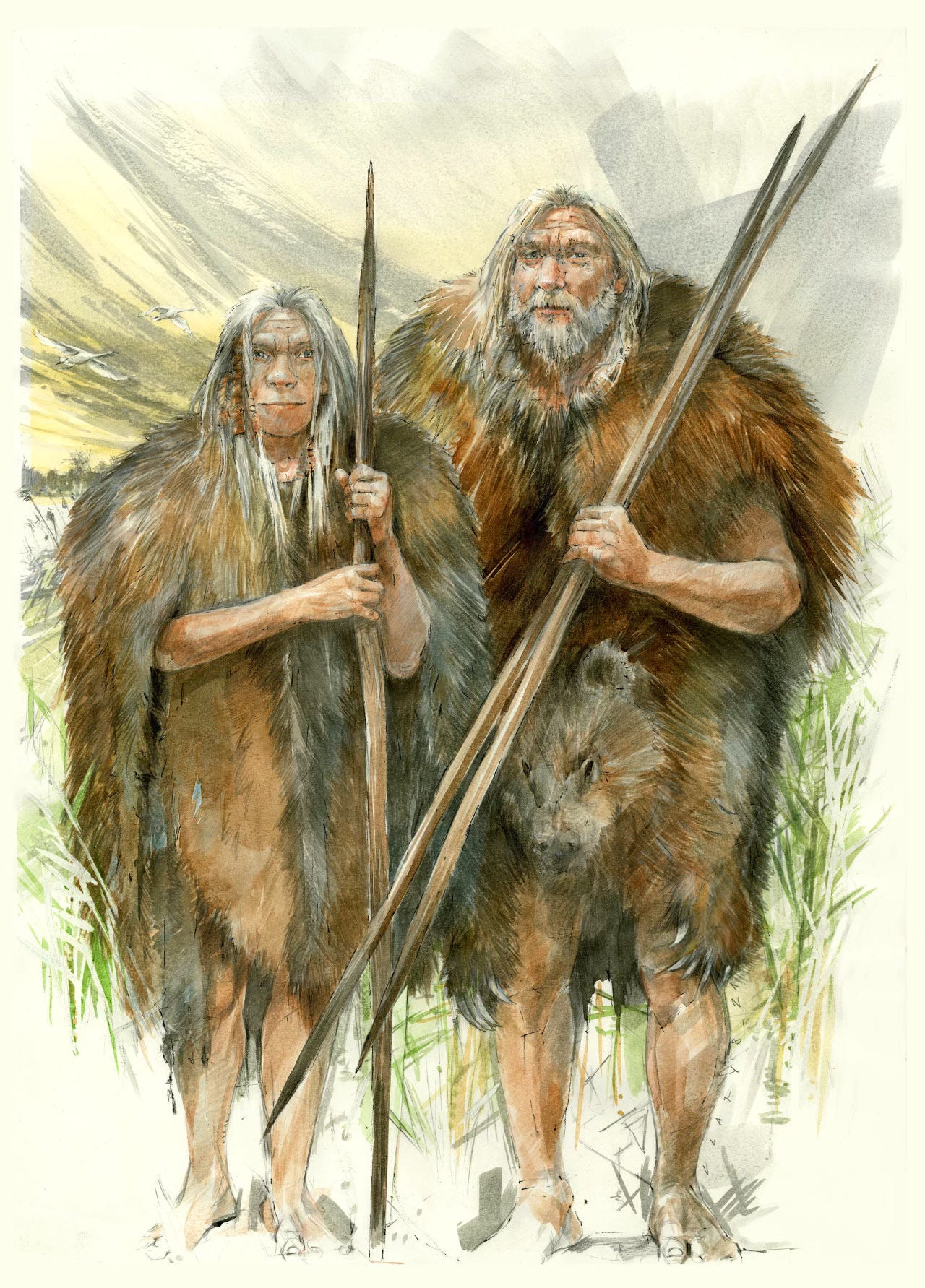

One key aspect of their success lay in their adeptness at hunting large animals. With innovative hunting strategies and specialized weaponry, early humans mastered the art of hunting even the most formidable mammals.

However, this success came at a considerable cost—the decline of other large mammals.

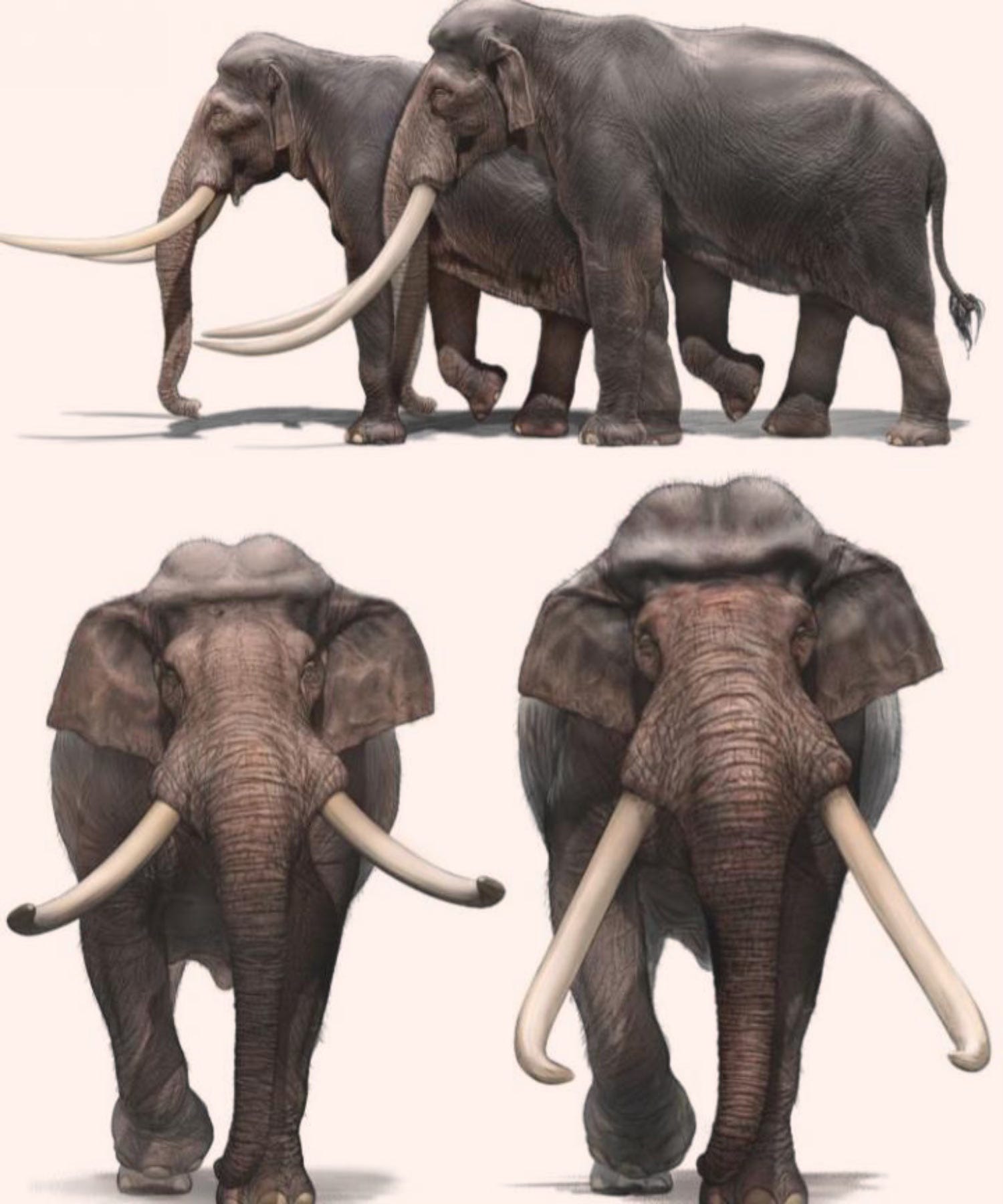

The extinction of numerous large species during the global expansion of modern humans is well-documented. New research1 from Aarhus University sheds light on an unexpected facet of this narrative: large mammals that survived this period also faced a significant decline.

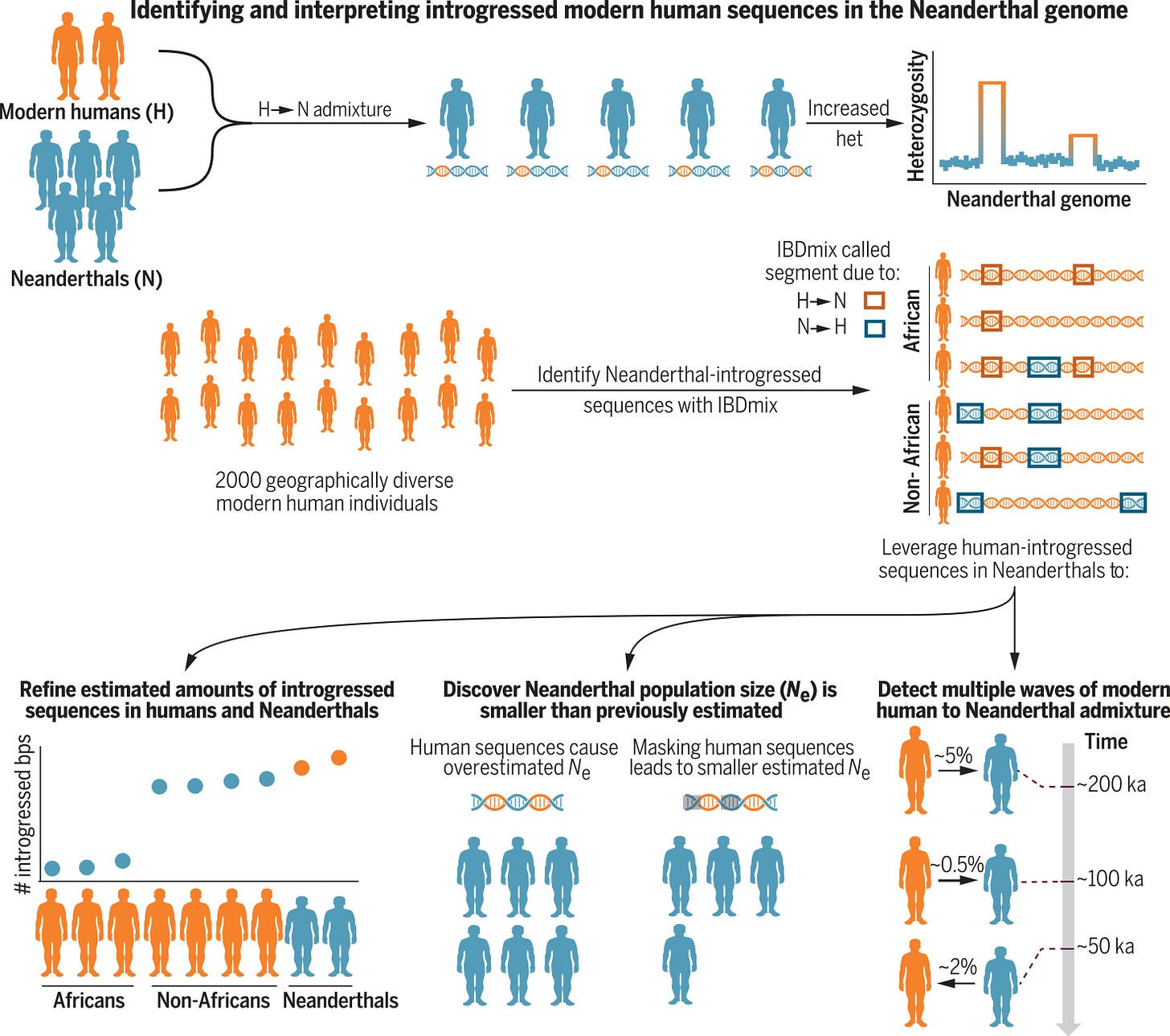

By studying the DNA of 139 extant species of large mammals, scientists discovered a remarkable downturn in the abundance of nearly all these species approximately 50,000 years ago. Jens-Christian Svenning, head of the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Ecological Dynamics in a Novel Biosphere (ECONOVO) at Aarhus University and the driving force behind the study, highlights this dramatic shift.

"We’ve delved into the evolutionary history of large mammalian populations spanning 750,000 years. For the first 700,000 years, populations remained fairly stable, but around 50,000 years ago, a significant and persistent decline occurred," he states.

The debate surrounding the extinction or decline of large mammals in the last 50,000 years has lingered among scientists. Some advocate for the view that severe fluctuations in climate played a pivotal role, citing the disappearance of the cold mammoth steppe as a contributing factor to the extinction of species like the woolly mammoth.

Conversely, another group attributes the prevalence of modern humans (Homo sapiens) as the primary cause. They argue that extensive hunting practices by our ancestors led to the complete extinction or severe reduction of various species.

The study's novel contribution lies in analyzing the DNA of 139 large living mammals—species that survived the last 50,000 years—revealing a consistent population decline linked to human expansion rather than climate change.

Advances in DNA sequencing have revolutionized our understanding of evolutionary history. Juraj Bergman, the lead researcher behind the study, explains how this methodology illuminates the past.

"We've gathered data from 139 extant large mammals, analyzing an immense amount of genetic information—approximately 3 billion data points from each species," Bergman elaborates. "DNA encapsulates extensive historical information. By grouping mutations and constructing a genetic family tree, we estimate population sizes over time."

Not all DNA mutations are influenced solely by population size. Environmental pressures, such as habitat changes or genetic mixing among isolated groups, can also impact mutation rates. To mitigate this variability, the researchers focused on analyzing neutral DNA segments less susceptible to environmental influences. These sections primarily reflect population size changes over time.

The classic argument correlating climate shifts with the extinction of megafauna species, particularly exemplified by the woolly mammoth, fails to capture the complexity of the situation. Svenning points out that most extinct megafauna species did not inhabit the mammoth steppe but thrived in temperate or tropical climates.

In light of extensive data, Svenning challenges the plausibility of a climate-based explanation for the worldwide extinctions and continual decline of megafauna since 50,000 years ago. He contends that human expansion, rather than climatic shifts, is the likelier cause of this selective loss.

The quest to unravel the truth behind the decline of giant mammals persists, but mounting evidence underscores the profound impact of human expansion on the ecological balance of our planet.

Bergman, J., Pedersen, R. Ø., Lundgren, E. J., Lemoine, R. T., Monsarrat, S., Pearce, E. A., Schierup, M. H., & Svenning, J.-C. (2023). Worldwide Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene population declines in extant megafauna are associated with Homo sapiens expansion rather than climate change. Nature Communications, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43426-5