By Alissa Whitmore Erica McCrystal’s ambitious Gotham City Living: The Social Dynamics in the Batman Comics and Media (2021) aims...

By Alissa Whitmore

McCrystal, Erica. 2021. Gotham City Living: The social dynamics in the Batman comics and media. New York: Bloomsbury.

Erica McCrystal’s ambitious Gotham City Living: The Social Dynamics in the Batman Comics and Media (2021) aims to trace the evolving representation of identity and criminality in the Batman universe, from the first comics in 1939 through 2019’s Joker film. The chapters range from documenting the challenges of growing up in Gotham to the ways in which the comics and films critique income inequality, but ultimately uphold capitalism by requiring a wealthy superhero to maintain order and fight crime. McCrystal’s central argument is that Batman’s home of Gotham City operates as a stand-in for any American city, with Gotham and its denizens – heroes and villains alike – being continually re-imagined in comics, tv, and film to tap into the cultural anxieties of the present day.

A Professor of Education and English at Centenary University, McCrystal is a media scholar whose research focuses on literature, comics, villains, and pop culture. While Gotham City Living is published by an academic press and targeted toward comic and literary scholars, McCrystal’s book is easily accessible for fans as well. Each chapter weaves academic theories with discussions of characters or comics, though a fuller introduction to some concepts would have been helpful for those with limited exposure to this scholarship.

Given the book’s short length (just over 200 pages), it is impossible for McCrystal to offer a complete analysis of social identity across 80 years of Batman media. The Batverse’s cast of familiar villains and allies (as well as some lesser-known characters) appear, but fans will undoubtedly notice gaps in coverage. For example, Harley Quinn’s abusive relationship with the Joker is briefly referenced in the text, but is absent from a section on “Problematic Relationships.” An analysis of Harley’s queer coded relationship with Poison Ivy – alluded to in Batman the Animated Series (1992-1995) before Harley’s bisexuality was more openly portrayed in DC Bombshells (2015-2017), Harley Quinn #25 (2016), Injustice 2 #70 (2018), and the current Max series Harley Quinn (2019- ) – would also have been a welcome addition to McCrystal’s section on challenging heteronormativity, which primarily focuses on queer readings of Batman and Robin’s close relationship in the early comics and Batwoman Kate Kane’s lesbian identity.

DC Comic’s tweet on queer coded comics featuring Harley & Poison Ivy.

DC Comic’s tweet on queer coded comics featuring Harley & Poison Ivy.Those interested in a deep dive might get more out of other Batman volumes devoted to a specific topic, like gender & sexuality (Richardson 2020) or psychology & criminology (Packer & Frederick 2019; Langley 2019, 2022), or books focused on specific characters, like Robin / Nightwing (Geaman 2015), Harley Quinn (Barba & Perrin 2017), or the Joker (Peaslee & Weiner 2015). What Gotham City Living offers is an introduction to scholarship on the Dark Knight and a survey of Batman comics, tv episodes, and films that have something interesting to say about identity in American culture.

Sex, Gender, and Violence in Gotham City

McCrystal organizes her text into six chapters, each focused on a separate facet of social identity (age, gender, sexuality, race, and class) with a final chapter looking at criminality. This division of identity into separate chapters is sometimes strained and results in the same storylines being discussed multiple times, such as the Joker’s assault on Barbara Gordon in The Killing Joke (1988), which appears in the chapters on gender and sexuality. These repetitions and the challenges of analyzing discrete identity characteristics without reference to others highlights the intersectionality of identity (Dastagir 2017; Steinmatz & Crenshaw 2020). A different type of organization, like focusing each chapter on the portrayal of multiple aspects of identity in a specific comic or tv series, or examining how depictions of poverty and capitalism change over time, might have provided McCrystal with the opportunity for a more nuanced analysis.

Given the vast significance of identity and the abundant scholarship on it, some chapters and sections are inevitably uneven. McCrystal’s chapters on gender and sexuality primarily focus on female characters, particularly Batwoman, Batgirl, Catwoman, and Poison Ivy. She argues that Gotham’s heroines and villainesses reflect changing and fluid perspectives on American femininity, but perhaps uncritically situates Batman as a largely unchanging embodiment of hypermasculinity. The chapter on sexuality likewise explores primarily how female characters have been sexualized, particularly Catwoman, who was deemed by the Comics Code (more on the Code below) to be too sexy for comics from the mid-1950s – 1960s. McCrystal does argue, however, that the sexuality of Batman, Robin, and other male heroes and villains is partially policed in that few characters get to have healthy romantic relationships.

In several cases, McCrystal introduces ideas and interpretations from other academics and media critics without fully engaging with the issues they raise. In her discussion of the Joker’s assault on Barbara Gordon, McCrystal begins by outlining the critique raised by comic writers and scholars that the storyline objectifies Barbara, making her into a plot device to advance Batman’s and her father’s character development (for more on this, see Backe 2016). Then McCrystal presents media scholar William Proctor’s argument that Barbara’s assault draws attention to real-world sexual violence, empowers victims to speak out about their own assaults, and elicits sympathy for victimized women. While McCrystal characterizes Joker’s attack as objectifying and hypersexualizing Barbara in a later chapter, here, she doesn’t problematize Proctor’s interpretation of The Killing Joke, but instead moves on to discuss Barbara’s evolution into the Oracle.

Proctor’s argument that there is value in Barbara’s callous treatment, that depicting an assault is necessary to elicit sympathy for rape victims, and that this depiction would be empowering for survivors – and McCrystal’s immediate pivot away after presenting this idea – landed hard for me. More discussion of Proctor’s supporting evidence for this interpretation, as well as presenting scholarship on media portrayals of victimization, would have helped readers contextualize and critically think through Proctor’s analysis, and it is a missed opportunity that McCrystal didn’t grapple with these two very contradictory interpretations of Barbara’s assault.

In contrast, the author devotes twice as many pages to a Batwoman (2014-2015) story arc in which the female vampire Nocturna poses as Kate Kane’s ex-girlfriend, rapes her, and hypnotizes Kate into believing that they are in a consensual relationship. McCrystal cites critiques raised by journalist Mey Rude that the comics visually portray Kate’s rape as sexy and arousing for the audience, which romanticizes rape and perpetuates rape culture. After creating space for this critique, McCrystal details the harm caused to Kate by Nocturna’s rape and how this storyline upends common myths about who can be a rapist, a survivor, and what rape and its aftermath can look like. As in the discussion of The Killing Joke, McCrystal doesn’t advocate for one interpretation or another, but the detailed discussion of rape in Batwoman helps readers sit mired in the problematic complexity of American media portrayals and ideas about rape and consent.

Gotham City Living is strongest when McCrystal presents hard, conflicting truths about the Batverse and, by extension, ourselves. Batgirl’s (2013-2015) inclusion of the first trans character in DC Comics, Alysia Yeoh as Barbara’s roommate, was revolutionary, but this doesn’t preclude accusations that the comic was transphobic when Batgirl was later shocked to discover that a villain dressed as Batgirl was a man. And the book is the weakest when McCrystal seems unwilling to consider critiques or multiple perspectives about the Batman universe. After citing numerous examples of Batman and Robin belittling and stealing credit from female characters, McCrystal asserts that the heroes aren’t misogynist, but are chivalrous protectors. They are both. Likewise, female villains can use their sexuality as a way to to gain power over men and cope with sexism; Selina Kyle’s role as a dominatrix in Batman: Year One (1987) can be both empowering and exploitative (see Weitzer 2010). Readers would have benefited from more fleshed-out examples of such conflicting interpretations, which illustrate the complexity of gender and sexuality in comics and real life.

Racism, Superheroes, and the Comics Code

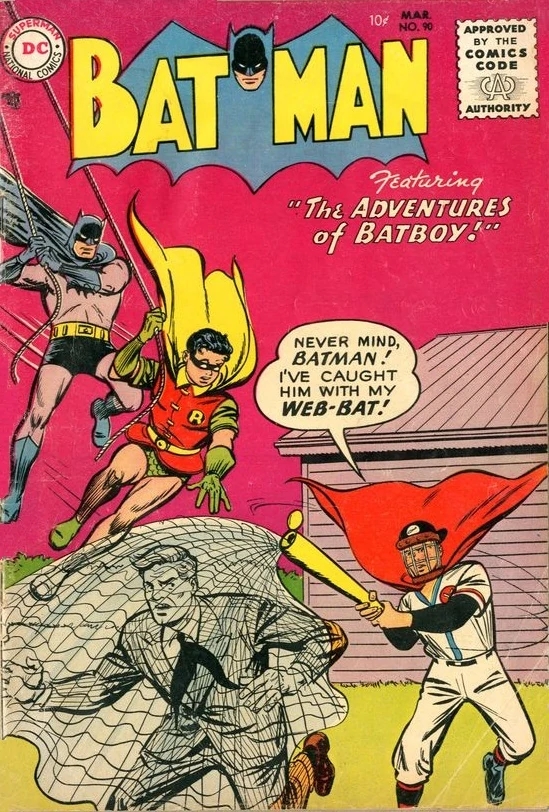

A central theme in Gotham City Living is how the Comics Code (1954 – 2011) shaped the portrayal of race, gender, sexuality, and violence in the Batverse. The code’s origins date to the 1940s, when concerns about comic content from educators and the Catholic Church were further inflamed by psychologist Dr. Fredric Wertham, who argued that sexual and violent content in comics stunts child psychological development and morality (Nyberg 2011). In 1954, a US Senate Subcommittee held hearings on the comic book industry and juvenile delinquency, and the Comics Magazine Association of America adopted the Comics Code as a way for the comics industry to moderate content themselves and attempt to stave off government regulation. Among other things, the code prohibited the inclusion of excessive violence, profanity, sexually suggestive illustrations and language, ridicule of religious and racial groups, and most supernatural creatures (seriously). The code was revised numerous times, before it was abandoned in 2011 (Nyberg 2011).

Batman #90 (1955) – The first issue with the Comics Code Authority’s stamp of approval. DC Comics.

Batman #90 (1955) – The first issue with the Comics Code Authority’s stamp of approval. DC Comics.Undoubtedly, the Comics Code had a tremendous impact on comic writers and artists. At times, however, McCrystal likely gives the code too much credit, particularly when discussing race. The central thesis of her chapter on race and ethnicity is that Batman comics promoted equality and inclusion, with the strongest supporting evidence being the relatively rare occurrences of overt racism and a few storylines from the 2000s featuring Black characters (including Orpheus and Grotesk) and discussions of gentrification, police brutality, and racial disparities in the justice system. But McCrystal struggles in her defense against critiques that the Batverse is predominantly occupied by white characters. While she includes statistics to suggest that the lack of early comic diversity may reflect real-world demographics of Black and Brown people living in 1940’s American metropolises, her primary defense is that “the Batman franchise’s creative teams have not neglected race as an exclusionary practice” but instead were 1) seeking to adhere to the Comics Code and 2) catering to their audience (McCrystal 10).

The language of the Comics Code prohibited “ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group,” and by extension, negative racial stereotypes. McCrystal argues that the Batman creators’ response to the Code was a progressive agenda for its time, whose “intentions [we]re to eliminate prejudiced racial formation in the minds of the readers through omission” (111-2).

But the Code only discouraged racist stereotypes – not the depiction of different racial groups themselves.

If comic creators and publishers, in seeking to adhere to a prohibition against negative depictions of Black people, completely avoid depicting Black characters, this is strong evidence of the pervasiveness of systemic racism in the comics industry and the wider culture. It suggests that comic creators (or those enforcing the Code) couldn’t conceive of portraying people of color without racist stereotypes, or as heroes or everyday folks living in Batman’s world. So they left Black and Brown people out entirely.

The practice of omitting racially diverse characters as an “acceptable” way to lessen prejudice and racism is fundamentally exclusionary and an example of color-evasion. Color-evasive ideology argues that racism can be eliminated by avoiding discussions of race or racism. It is often used to assert a lack of racism (e.g. “I don’t see race”, “I don’t think about race when I interact with people”) and was once held up as a “progressive” ideal, but it has been strongly critiqued for perpetuating racism by refusing to recognize its existence and denying the experiences of people of color (Bonilla-Silva 2013; Wingfield 2015). An adherence to color-evasion is particularly evident in Batman comics during the Civil Rights era of the 1950s and 1960s, when the universe remained predominantly white and, in contrast to reality, Gotham was “an American city where racial tensions essentially did not exist” (McCrystal 111).

The Batman team’s color-evasive response to the Code was exclusionary and prejudiced. Outside of the Batverse, there is evidence that the Code was used to stifle positive portrayals of Black protagonists and discussions of racism in other comics during the 1950s (Yezbick 2015), further illustrating racism within the industry and situating the Code as a tool for maintaining whiteness in comics.

McCrystal’s also argues that the “hyper-white” appearance of the Batverse reflects “an industry that must meet consumer demands” with readers being a “strong determinant of content – whether for inclusion or not” (103). Batman comics were created by a predominantly white industry which was targeting a predominantly white, young, male audience, who, it was assumed, only wanted to see reflections of themselves on the pages.

The whiteness of Batman’s universe can be seen as an example of white centering. Layla E. Saad notes the pervasiveness of whiteness in American popular culture, which often centers white stories, characters, norms, and values. White centering is the assumption that a film with a predominantly white cast will appeal to all audiences, but that movies featuring primarily actors of color wouldn’t be relevant to white people. Centering whiteness as the norm and marginalizing people of color is a form of white supremacy, and one which can be more difficult to detect than more overt examples of racism (Saad 2020).

But, like color-evasive ideology, white centering is racism.

And this racism is often revealed when white fans lash out against re-imagined pop culture classics that de-center whiteness by casting actors of color (see also Backe 2022). Writing about The Rings of Power and the new live-action The Little Mermaid, pop culture critic Eric Deggans notes that most iconic science fiction, fantasy, and superhero stories have excluded people of color and that “enshrining beloved characters as forever white is the very definition of white privilege.”

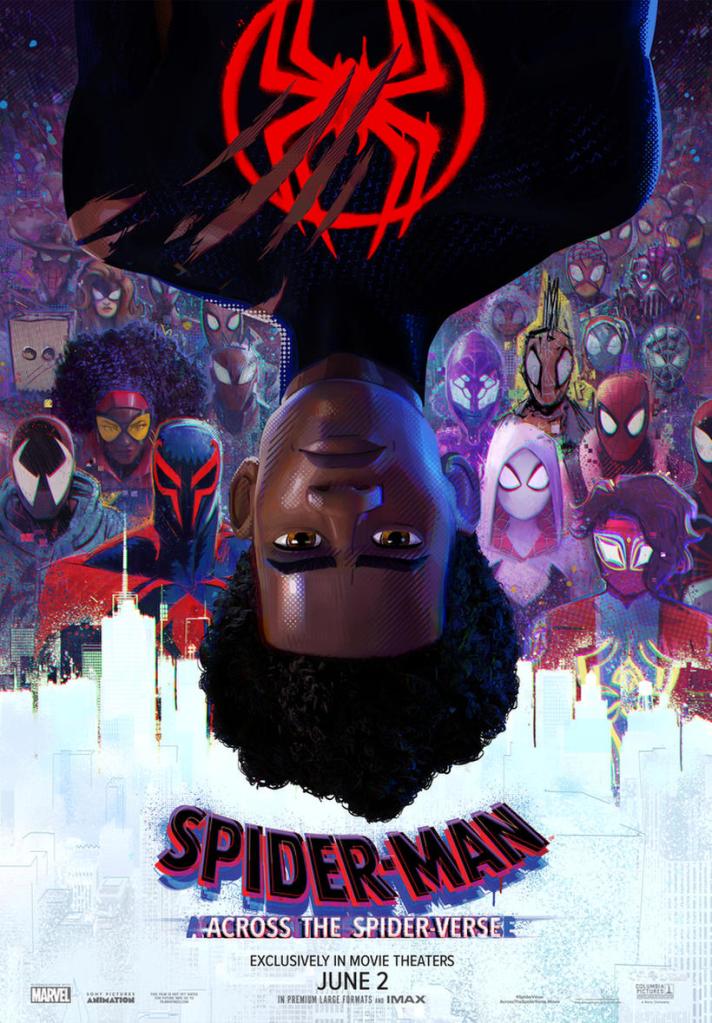

Poster for 2023’s Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Sony / Marvel.

Poster for 2023’s Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Sony / Marvel.Sociologist Albert S. Fu analyzed online fan opposition to the suggestion that Black actor Donald Glover should be cast as Spiderman and the creation of Miles Morales as a Black, Puerto Rican Spiderman. Fu notes that white fans call upon the canon – the official or popularly recognized history of a character or fictional universe – to call for Peter Parker’s whiteness in future pop culture iterations and to deny accusations of racism for not wanting a Black actor playing Spiderman. In making this argument, fans treat the canon as “colorless history,” while ignoring the real-world history that largely excluded people of color from creating or playing central roles in these narratives (Fu 2015). In this way, the canon (which is constructed through white supremacy’s racist ideas of who can be a hero) is weaponized to maintain white supremacy through normalizing whiteness, further excluding people of color, and defending against accusations of racism. Marvel’s new Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse film offers excellent commentary on this by directly questioning whether the canon is good or necessary and situating it as an obstacle for Miles and other Spider-People.

McCrystal argues that in keeping the Batverse white, DC’s intentions may not have been exclusionary – they were just sticking with a formula that proved profitable and presumed that stories featuring diverse casts wouldn’t make as much money. This type of argument illustrates the connections between racism and capitalism, intertwined systems which perpetuate one another (see Wolff 2016; Desmond 2019). In this case, the racist decision to exclude people of color from Batman comics is justified by capitalism’s emphasis on maximum profit, and this exclusionary media that then is sold to the public helps support the perception of a predominantly white world, devoid of good people of color.

McCrystal briefly acknowledges that excluding people of color from the Batverse creates a “product that appears to be rooted in white hegemonic capitalistic practices” (108), whose treatment of race may be “misguided” (112). But she largely seems hesitant to call out the racist impacts (or intents) of creating and maintaining a predominantly white Gotham City, repeatedly stating that the Batman team was making a positive, progressive choice since they didn’t portray people of color as villains and were following the Code.

Over time, representation of people of color in superhero stories has increased. McCrystal cites examples of a 1950s Batman PSA encouraging racial tolerance in sports, Eartha Kitt’s portrayal of Catwoman in the 1960s Batman tv show, and scattered comic story arcs starting in the 1990s that feature Black superheroes and villains and critiques of racism and xenophobia. But these feel like exceptions that prove the rule.

In a CodeSwitch conversation about race and superheroes, Kendra Pettis notes that cartoons often feature racially diverse heroes, perhaps specifically to appeal to children of color, but heroes of color are still largely missing from comics and films geared toward adults. Bryan Cooper Owens argues that this is because adults prefer the white superheroes that they grew up with, which helps maintain the revolving door of superheroes of color who are created and then canceled. Owens argues that the comics industry views racebending established characters (recasting them in a new race or ethnicity) as a way to more accurately reflect our multiracial society in a way that is deemed safer for sales, and one which doesn’t genuinely challenge the overall whiteness of comics, despite disagreements from some vocal white fans.

Overall, however, it remains difficult to agree with McCrystal’s analysis that Batman comics have largely and historically “discouraged prejudiced thinking and promoted equality and inclusivity” (104).

Conclusion: The End of the Knight

McCrystal ends Gotham City Living with a two paragraph Epilogue, referencing 2022’s upcoming The Batman movie and noting that just as Batman comics and media have reflected and shaped social mores in the past, they will continue to do so in the future.

At the end of the book, I had hoped for a more robust conclusion that tied together the sometimes disparate chapters. Or one that answered the all-important question – so what? McCrystal’s overarching and uncontroversial thesis is that Batman’s universe has grown more socially progressive over time, influenced by broader changes in American culture. Anthropologists and social scientists have a keen interest in understanding cultural change, but Gotham City Living stays close to the surface in documenting these changes and the ways in which Batman stories often reflect American cultural concerns, rather than delving into the broader meaning of social progress and the tensions that come with cultural change. I was also left wondering whether there is anything unique about the evolution of Gotham City and the identities of its inhabitants – or comics – in comparison to other long-running fictional universes. Because while I care (perhaps too much) about the Batverse, I’m not certain that this book will convince others to do so.

Mary Hamilton-Kane & Marquis Jet as new iterations of Poison Ivy and Joker. Batwoman, Season 3, Episode 8, “Trust Destiny.”

Mary Hamilton-Kane & Marquis Jet as new iterations of Poison Ivy and Joker. Batwoman, Season 3, Episode 8, “Trust Destiny.”

Where McCrystal’s text shines is by offering a history of Gotham City. I was struck by how large the Batverse is and how quickly new iterations emerge. Newer tv shows, like Titans (2018-2023) and Batwoman (2019-2022), likely came out after the book was written, which is a shame given Batwoman’s rich portrayals of gender, sexuality, race, and villainy. Tim Drake’s Robin didn’t come out as bisexual until 2021. And an analysis of 2022’s shelving of the completed Batgirl movie – which featured a Latina Batgirl played by Leslie Grace, trans actress Ivory Aquino playing Alysia Yeoh, and Muslim, Belgian Moroccan filmmakers Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah – allegedly for DC to get a tax write-off, would have been most welcome, as this saga surely says something interesting about identity and capitalism in modern American culture.

If readers are looking for an introduction to academic scholarship on comics and identity, Gotham City Living provides a good entry point. But readers with a firm grounding in anthropology, sociology, or academic research on identity will likely be left wanting more.

Works Cited

Barba, Shelley E. & Joy M. Perrin. (eds.) 2017. The Ascendance of Harley Quinn: Essays on DC’s Enigmatic Villain. McFarland.

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2013. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. Rowman & Littlefield.

Fu, Albert S. 2015. Fear of a black Spider-Man: Racebending and the colour-line in superhero (re)casting. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 6(3): 269-283. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271212845_Fear_of_a_black_Spider-Man_Racebending_and_the_colour-line_in_superhero_recasting

Geaman, Kristen L. (ed.) 2015. Dick Grayson, Boy Wonder: Scholars and Creators on 75 Years of Robin, Nightwing, and Batman. McFarland.

Langley, Travis (ed). 2019. The Joker Psychology: Evil clowns and the Women who Love Them. New York: Sterling.

Langley, Travis (ed.). 2022. Batman and Psychology: a Dark and Stormy Knight. 2nd ed. Wiley.

Packer, Sharon & Daniel R. Frederick. (eds.) 2019. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland.

Peaslee, Robert Moses & Robert G. Weiner (eds) 2015. The Joker: a Serious Study of the Clown Prince of Crime. University Press of Mississippi.

Richardson, Chris. 2020. Batman and the Joker: Contested Sexuality in Popular Culture. Routledge.

Saad, Layla. 2020. Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor. Sourcebooks.

Weitzer, Ronald. 2010. The Mythology of Prostitution: Advocacy Research and Public Policy. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 7(1): 15-29. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227027069_The_Mythology_of_Prostitution_Advocacy_Research_and_Public_Policy

Yezbick, Daniel F. 2015. “No Sweat!” EC Comics, Cold War Censorship, and the Troublesome Colors of “Judgment Day!” In The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black identity in comics and sequential art, ed. Frances Gateward & John Jennings. Rutgers University Press.