By Christopher Marcatili McGavin, Kirsten (ed.). 2022. World Beyond: An anthology of Papua New Guinean Speculative Fiction. Sydney, Aus: Hibiscus...

By Christopher Marcatili

McGavin, Kirsten (ed.). 2022. World Beyond: An anthology of Papua New Guinean Speculative Fiction. Sydney, Aus: Hibiscus Three.

In the remote mountains of Papua New Guinea (PNG), Aula walks the jungles accompanied by her large magpie, Ko. There she hopes to find the spirit, Large Bird, and ask him to protect her from Kiki, the chief’s son. Far away in time, but perhaps not so far in space, Isla Grace is a Seeker, defending her domed community from the jade – a race of humans who have stripped the earth of its natural beauty and resources. Or so she has been told. And many generations in the future, the success of interstellar exploration relies on sago, a starch extract from tropical palms grown and genetically engineered in PNG. These and six other short stories written by Papua New Guinean authors are presented in World Beyond: An Anthology of Papua New Guinean Speculative Fiction (McGavin, 2022).

Storytelling has been and remains at the heart of holding and sharing PNG indigenous knowledge of culture and place across generations (Tove Stella, 2009; Rumsey, 2000). These are the histories, mythologies, practices – the stori and kastom – of the many peoples that have called PNG home for generations. From the shark-hefting warrior of Alewai, a story told by the Vula’a in the southeast (Van Heekeren, 2012), to Mendangumeli, a crocodile spirit at the heart of a flood myth, told by Sepik communities in the north (Silverman, 2016), these oral histories were historically only consigned to paper by ethnographers. In this process of ‘cultural translation’, anthropologists must be mindful that they engage in ‘conditions of power’ that subordinate non-Western cultures and histories. This can occur in myriad ways, including the development of privileged scientific truth-statements about a given people that they often cannot easily contest or, at times, even access (Asad, 1986, p. 163).

In PNG, it has been less common to see indigenous authors and academics asserting their own interpretations of their lifeworlds in the realm of fiction, which makes World Beyond a significant contribution to Pasifika literature. According to Kirsten McGavin (2022), editor of this anthology, The Erstwhile Savage (Linge, 1932), an autobiography, was the first book published by a Papua New Guinean. In the 1950s, the anthropology journal Oceania published poetry by a Mekeo man from Central province. The first novel published by a Papua New Guinean was The Crocodile, by Vincent Eri in 1970. While indigenous PNG authors have continued to publish, low levels of literacy in some regions, linguistic diversity across the country, and the impacts of PNG’s colonial history on its cultural and academic spheres have presented challenges (Fitzpatrick, 2021). The lack of government support for writers, the closure of libraries, and a lack of interest from international publishers in authors from the Global South have all further contributed to more recent declines in PNG literature (Fitzpatrick, 2016). As McGavin points out, the publishing world is full of gatekeepers who do not understand the voices of PNG authors: “this kind of gatekeeping is probably the reason why there have not been more Papua New Guinean writers in print” (2022, p. ix).

Despite these challenges, World Beyond adds to this series of firsts as the first speculative fiction anthology entirely by PNG authors. It includes stories like ‘Ravalian’, by Vanessa Gordon, which questions the role of traditional magic in the protection of sacred places from environmental degradation. Or Jeremy Hau’ofa Mogi’s ‘Pale Moon Shadow’, a story warning of the dangers of toying with the magics of a witch doctor. This original anthology is a fresh, raw collection speaking with the voice of PNG; though the majority is written in English, much of the dialogue in some stories is in the creole Tok Pisin without translation.

As a Western reader unfamiliar with Tok Pisin, this elicited a mix of reactions from me. There was the sense of immersion in the unknown that many readers of SFF love. When done well, a balance between the unknown and the familiar allows the reader to draw meaning from the context without exposition. I often attempted to parse meaning from words and lines that, when read out loud, vaguely hint at their English influences (for example, the line ‘Yu save tingting, tu?’, meaning ‘Do you ever wonder?’, repeated by Deborah Salle in her story ‘The Sago Pill’). This forced me to slow my reading and engage in the text with a level of care often missing when I read for pleasure. There was also an occasional sense of alienation – that this book was not for me, or that I might not be its intended audience. In several stories, like Augustine Minimbi’s ‘Tomait, Meet Malipu’, in which a young student travels back in time to meet the first Highlands politician who intended to run for Prime Minister before he was assassinated, whole lines of dialogue and internal monologue are not in English. The inclusion of indigenous phrases and language never makes the stories incomprehensible to non-speakers, yet it is a reminder that the anthology is distinctly and unapologetically Papua New Guinean, written for and by those deeply interested in that country, its languages, peoples, and culture.

Across each of these stories, themes relating to PNG cultural identity emerge, speaking to issues of traditional knowledge and the environment. In ‘Ravalian’, for example, Kurai’s father, Elias, has been let go from the local mine because of his strong environmental views. He has spent months railing against the greed and corruption of the government while living on the beach at the ravalian, a place where Kurai’s “spirit and the spirit of the volcano and the ocean surrounding it meet” (Gordon, 2022, p. 100). When Kurai and Elias pull dead fish from the ocean, she wonders if their deaths are linked to climate change and the rising sea tides. But her father claims it is a curse, one that can only be defeated through ritual: “As he walked around the campsite, it was as though he was casting a spell into the sky and towards the sea, hoping that the trade winds carried the spell out to the deep blue sea– to the a ta na lau” (Gordon, 2022, p. 105). Elias attempts a ritual to reconnect with traditions of his people thousands of years old, but his efforts are fruitless. “I am not the one who can travel back,” he explains. “The power is in the woman […] The curse can only be broken by a female. We are a matrilineal society” (Gordon, 2022, p. 110).

In dealing with contemporary issues like the impacts of climate change, while at the same time acknowledging the role played by kastom, the authors also imagine new ways the country and its peoples might exist into the future. World Beyond appears to be, in short, an example of ‘ethnofuturism’.

Ethno- and other futurisms

Ethnofuturism is an aesthetic and artistic movement that prioritises marginalised cultural/ethnic groups and creates a space for them to draw on their own histories, stories and creative practices to imagine ways they might continue to exist that resists cultural hegemony or integration (Heith, 2018). When the term was originally coined in 1988 by writer Karl-Matrine Sinijärv in Estonia, it referred to the cultural and creative practices of the Finno-Ugric peoples in the twilight of the Soviet Union (Kolcheva, 2015; Minniyakhmetova, 2014; Hennoste, 2012). It was taken up by local avant-garde writers, artists and poets of the moment who wanted to find a way to resist their works being subsumed into generic Soviet cultural norms and instead to be distinctly Estonian. They studied the languages of their grandparents, travelled to the countryside, and blended folklore and ceremonial ritual into contemporary art and poetry (Kolcheva, 2015). In short, ethnofuturism blends the “indigenous, authentic, and prehistoric” with the “cosmopolitan and urban” (Minniyakhmetova, 2014, p. 217).

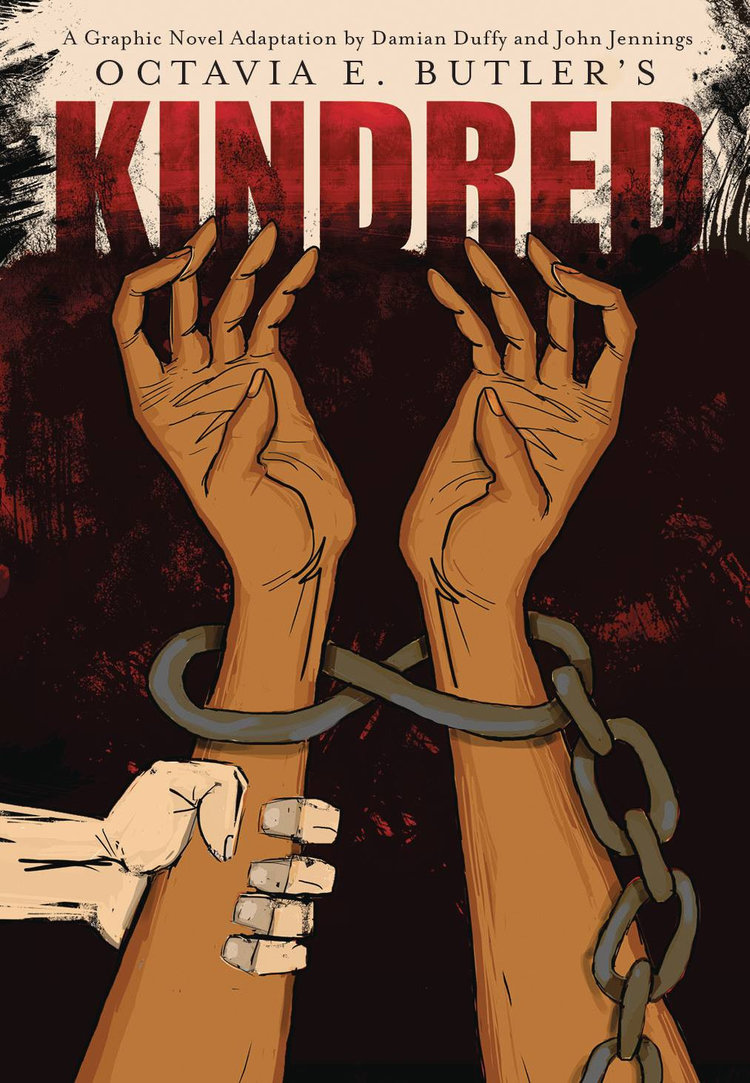

It has been said that “there is no ethnofuturism without Afrofuturism” (Shiu, 2014, p. 300). Afrofuturism was coined only a few years later, in the early 90s, by Mark Dery. Dery looked at speculative fiction at that time and found it peculiar that there were so few African American authors in the genre: “This is especially perplexing in light of the fact that African Americans, in a very real sense, are the descendants of alien abductees; they inhabit a sci-fi nightmare” (1994, p. 180). Broadly speaking, Afrofuturism includes approaches to speculative fiction, storytelling, or creative works from the African diaspora in America (Yaszek, 2006) that draw on imagination, technology, and liberation (Womack, 2010). From its outset, Afrofuturism emphasised struggle and freedom to a greater extent than ethnofuturism. Through speculative fiction, art, music, and other forms of creative expression, African Americans explore and challenge the ongoing impacts of racial oppression in the technoculture of the present to conceptualise futures that challenge or differ from the predominant, white American culture (Womack, 2010; Dery, 1994). Afrofuturism examples include novels like Kindred, by Octavia Bulter, or Binti, by Nnedi Okorafor, films like Black Panther, and albums by the avant-garde jazz musician Sun Ra.

Left: Cover image of Octavia Butler’s Kindred, graphic novel adaptation by Damian Duffy and John Jennings. ABRAMS Books. Right: Sun Ra. 1973. Unattributed photo promoting the re-issue of the album The Magic City from Impulse! Records and ABC/Dunhill Records. Wikicommons.

Cover image of Walking in the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction, ed. Grace Dillon. University of Arizona Press.

Cover image of Walking in the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction, ed. Grace Dillon. University of Arizona Press. More recently, ‘ethnofuturism’ has been decoupled from its geographic and ethnic specificity in Estonia and has instead been used more broadly to “rethink concepts such as identity, subjectivity, and relation” (Shiu, 2014, p. 300). Ethnofuturism centres the voices of those who are typically silenced or expected to assimilate to the dominant culture, and creates a space where they can imagine at times radically different ways of being or living than the circumstances they currently inhabit. In that sense, ethnofuturism has taken on a broadly anti-colonial sentiment, available to peoples around the world to use as a means of imagining how current circumstances may be different in a way that more fully expresses their own specific worldviews. Little wonder, then, that other futures and futurisms now proliferate, including Sinofuturism (de Seta, 2020), Cambrofuturism (Dyfrig, 2015), Chicanafuturism (Ramírez, 2008), Gulf and Arab futurism (Parrika, 2017) and Indigenous futurism (Guzmán, 2015; Dillon, 2012). McGavin positions World Beyond at the intersections between “Black, Indigenous and Islander futurism” (2022, p. x). While these various approaches to ethnofuturistic literature are diverse and may produce wildly different – perhaps even conflicting and contrasting – visions of the future, they are the same insofar as they complicate the traditional Western and white-washed vision of other worlds and times that has dominated SFF for so long.

It is within this context of rejecting colonialist subjugation that a collection like World Beyond is both timely and necessary in PNG. In SFF and other genres, there is an increasing movement toward ‘own voices,’ that is, underrepresented peoples and identities telling their own stories. While McGavin acknowledges this trend, she notes that it is often framed by cis-gendered Anglo-Saxons as an anxiety about who has the right to tell which stories. McGavin argues the importance of this shift is less about creating boundaries to dictate who is ‘allowed’ to write certain stories and instead is more about “making space for everyone else – all the rest of us who’ve struggled to push past gatekeepers who […] don’t understand our worldview” (2021, p. ix). Within the pages of World Beyond, PNG authors portray their own visions for the future and access a world that they previously might never have encountered.

The term, ‘World Beyond’ is fitting for a number of reasons. In our titular use of the term, it is reflective of our country’s new written literary frontier: the world beyond thousands of years of oral literature. It is the world beyond all the previously closed gates on the pathway to publication. The world beyond what we have seen represented in popular media – beyond our stereotypes, beyond our absence, beyond our relative invisibility. It is the world beyond our present circumstance.

– McGavin, 2022, p. xi

World Beyond presents stories that in many ways will be familiar and enjoyable to anyone who loves SFF genres and tropes. But for those who tend to read stories written by Western – mostly white, mostly male – authors, it also presents a particular opportunity: these stories, written at intersections of multiple othered identities at times break from the usual tropes in ways that can be challenging and exciting and offer new ways of imagining how the world might be different than it is now. The efflorescence of ‘futurisms’ can only mean more voices, more perspectives, more diversity, and therefore, more stories.

The anthropology of other worlds

Like SFF, anthropology has been grappling with a history of silencing minoritized voices. Since identifying the issue in the 1960s, anthropologists have more recently begun taking steps to redistribute power – both discursive and material – within the discipline (Harrison, 1997, p. 1), for example by de-centering the ethnographer’s voice or the ethnography itself as being the final authority on a given cultural context, and recognizing other local forms of knowledge (Lassiter, 2001). But the value for anthropologists of World Beyond and other creative works like it is more than just a celebration of creatives from marginalized communities finding and making platforms for their own voices. At least since Geertz (1973), anthropologists have raised questions and critiques of the capacity for ethnography to convey scientific absolutes. There has been a subsequent growing discourse around the relationship between ethnography, truth claims, creativity, and literature. Clifford (1986) added to this debate, suggesting that ethnography is itself a type of fiction not in the sense of being false, but in the sense of being intentionally crafted and therefore inevitably leaving some things out.

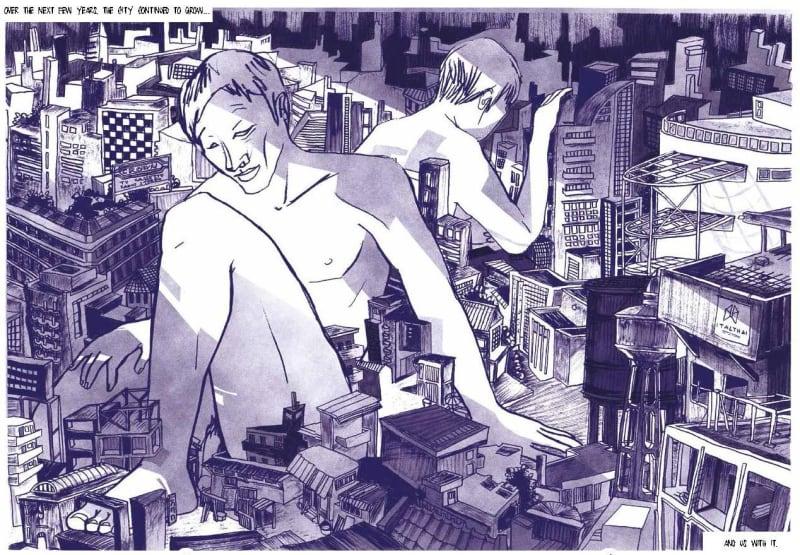

Fiction can offer fertile grounds for anthropologists. Reading, engaging with and even replicating the techniques of fiction through creative experimentation can be a means by which ethnography at least questions and challenges its colonial heritage, and may even navigate otherwise thorny ethical issues. For example, in an article explaining his graphic ethnography, The King of Bangkok (Sopranzetti, Fabbri & Natalucci, 2021), anthropologist Claudio Sopranzetti explains that by amalgamating the very real experiences of political activists in Thailand into fictionalized characters and situations, he is able to convey the complexities of their struggles while reducing the very real political risks to his interlocutors (Sopranzetti, Fabbri & Natalucci, 2022). Other intersections between anthropology and fiction have included identifying novels as potential ethnographic source material (Narayan, 1999), and using literary techniques to bring ethnographic and theoretic research to a broader, non-academic audience (Laterza, 2007).

Artwork detail from The King of Bangkok (Sopranzetti et al., 2021). University of Toronto Press.

Artwork detail from The King of Bangkok (Sopranzetti et al., 2021). University of Toronto Press.But what ethnographic value might be derived from speculative fictions set centuries in the future? One criticism of anthropology is that “anthropologists have contributed to a chronopolitical domination of ‘the other,’ consigning less developed societies to the status of ‘primitives’ temporally removed from capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism” (Collins, 2003, p. 180). Locating these peoples and cultures in the present, with their own desires for their own futures, goes some way to acknowledging their specific lifeworlds. The future-focused fictions written, for example, by contemporary Papua New Guinean speculative fiction authors reveals some of the key ways they dream the world might otherwise be, which in turn offers insights into their hopes, beliefs, and values, as well as real world contemporary challenges.

Christopher Marcatili is a fiction author, professional copy editor, and researcher living on the unceded lands of the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples (Canberra, Australia). He is currently completing a PhD in Anthropology at the Australian National University, focusing on the anthropology of creativity and creative writing in Iceland. He also holds a Masters of Creative Writing and writes weird and queer fiction. Find out more at www.christophermarcatili.com.

If you’d like to write a book review for us, please see our Call for Reviewers and the books available for review.

References

Asad, Talal. 1986. ‘The Concept of Cultural Translation in British Social Anthropology’ in Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Clifford, James. 1986. ‘Introduction: Partial Truths’ in Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Collins, Samuel G. 2003. ‘Sail on! Sail On!: Anthropology, Science Fiction, and the Enticing Future’ Science Fiction Studies 30: 180–198.

De Seta, Gabriele. 2020. ‘Sinofuturism as Inverse Orientalism: China’s Future and the Denial of Coevalness’ SFRA Review 50(2–3): 86–94.

Dillon, Grace L. (ed.). 2012. Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction, University of Arizona Press.

Dery, Mark. 1994. ‘Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose’ in Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, M. Dery (ed.), Durham and London : Duke University Press, pp. 179–222.

Dyfrig, Rodri. 2015. ‘Cambrofuturism: Welsh UFOs, alien, and futurists’ Medium. Accessed 21 August 2022 via https://medium.com/@nwdls/cambrofuturism-5df99c0999df

Eri, Vincent. 1970. The Crocodile. Penguin Books.

Fitzpatrick, Phil. 2016. The lost creative writing generation of Papua New Guinea. PNG Attitude. Accessed 7 December 2022 via https://www.pngattitude.com/2016/12/the-lost-generations-of-creative-writers-of-papua-new-guinea.html

Fitzpatrick, Phil. 2021. Literature in Papua New Guinea Part One: Traditional Publishing Begins. Papua New Guinea Association of Australia. Accessed 7 December 2022 via https://pngaa.org/article/literature-in-papua-new-guinea-part-one-traditional-publishing-begins/

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Gordon, Vanessa. 2022. ‘Ravalian’ in World Beyond: An Anthology of Papua New Guinean Speculative Fiction (pp. 99–116). Sydney, Aus: Hibiscus Three.

Guzmán, Alicia Inez. 2015. Indigenous Futurisms. InVisible Culture. Accessed 2 September 2022 via https://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/indigenous-futurisms/

Harrison, Faye V. 1997 [1991]. Decolonizing Anthropology: Moving further toward an anthropology of liberation. Arlington, Virginia: American Anthropological Association.

Heith, Anne. 2018. ‘Ethnofuturism and Place-making: Bengt Pohjanen’s Construction of Meänmaa’ Journal of Northern Studies 12(1): 93–109.

Hennoste, Tiit. 2012. ‘Ethno-Futurism in Estonia’ International Yearbook of Futurism Studies 2(1): 253–85.

Kolcheva, Elvira M. 2015. ‘Formation of Ethno-Futurism at the Turn of the XX-XXI Centuries’ Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6(3): 231–36.

Lassiter, L. E. 2001. ‘“Reading over the shoulders of natives” to “reading alongside natives,” literally: toward a collaborative and reciprocal ethnography’ Journal of Anthropological Research 57(2): 137–149.

Laterza, Vito. 2007. ‘The Ethnographic Novel: Another Literary Skeleton in the Anthropological Closet?’ Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society 32(2): 124–134.

Linge, Hosea. 1932. The Erstwhile Savage: An Account of the Ligeremaluoga (Osea), Melbourne, F.W. Cheshire Pty. Ltd., 1932.

Minniyakhmetova, Tatiana. 2014. ‘Ethno-Futurism as a New Ideology’ Politics, Feasts, Festivals 4: 217–23.

Narayan, Kirin. 1999. ‘Ethnography and fiction: Where is the border?’ Anthropology and Humanism 24(2): 134–147.

Parrika, Jussi. 2017. ‘Middle East and other futurisms: Imaginary temporalities in contemporary art and visual culture’ Culture, Theory and Critique 59(1): 40–58.

Ramírez, Catherine. 2008. ‘Afrofuturism/Chicanafuturism: Fictive kin’ Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 33(1): 185–194.

Rumsey, A. 2000. ‘Tracks, Traces, and Links to Land in Australia, New Guinea and Beyond’ in Emplaced Myth: Space, Narrative, and Knowledge in Aboriginal Australia and Papua New Guinea, Alan Rumsey & James Weiner (eds.). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Shiu, Anthony Sze-Fai. 2014. ‘The Ethics of Race, Failure, and Asian American (Ethno)Futures’ Extrapolation 55(3): 299–321

Silverman, Eric. ‘The Waters of Mendangumeli: A Masculine Psychoanalytic Interpretation of a New Guinea Flood Myth— and Women’s Laughter’ Journal of American Folklore 129(512).

Sopranzetti, Claudio, Fabbri, Sara & Natalucci, Chiara. 2022. ‘Dialogues: The King of Bangkok: A collaborative graphic novel’ Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 28: 1012–1052.

Sopranzetti, Claudio, Fabbri, Sara & Natalucci, Chiara. 2021. The King of Bangkok. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Tove Stella, R. 2009. ‘Narratives and Narrators: Stories as Routes to Indigenous Knowledge in Papua New Guinea’ The IUP Journal of Commonwealth Literature 1(1)

Van Heekeren, Deborah. 2012. The Shark Warrior of Alewai: A Phenomenology of Melanesian Identity. Wantage, England: Sean Kingston Publishers.

Womack, Ytasha. 2010. Post-Black: How a New Generation is Redefining African American Identity. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

Yaszek, Lisa. 2006. ‘Afrofuturism, Science Fiction, and the History of the Future’ Socialism and Democracy 20(3): 41-60.