By Luna Kvarnstrøm Melgaard MSc Anthropology, Environment, and Development We are understandably looking for someone to blame regarding climate change. However, this is a problematic approach since the problem and its solutions are complex.

By

Luna Kvarnstrøm Melgaard

MSc Anthropology, Environment, and Development

Why is the aviation industry worth talking about?

We have all heard how harmful the aviation industry is to the climate. The focus on this topic increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now more than ever, flying is viewed as an irresponsible activity, without much debate. The criticism of the aviation industry spread like wildfire. Moreover, an anti-flight movement has emerged known as ‘flight shaming’, which was promoted by environmental activist Greta Thunberg. Flying has become a means of transport that many people associate with guilt and try to avoid entirely or minimise as much as possible, as Sara shares her view:

“I make sure I am packing in as many events and speaking engagements as possible … so that I can justify I can take that flight.”

—Sara, student at UCLThe anti-flying movement increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, perhaps because many of us were at home and had more time than ever to care about the news or maybe because it seemed like an easy target. Nevertheless, few people have the full picture, of why and how the aviation industry is bad for the climate.

“I feel guilty flying. I would rather take a train … I don’t know too much about the details about why, just that it is bad.”

—Hannah, student at UCLWhile the aviation industry is doing nothing good for the environment and is hard to abate, the dilemma is: Should we stop flying? The facts we are given in the news are limited, but let’s unpack them a bit.

The consensus is that the CO2 footprint of aviation is around 2-3% of all human-produced carbon emissions. To put this into perspective, aviation accounts for around 11% of transport emissions, compared to road travel which accounts for around 45% (Ritchie 2020). It is important to understand the distribution of the flights. While flying has increased and become more accessible, few of us fly enough to make much of an environmental impact. Globally only 20% of people have ever flown and, moreover, it is the wealthiest 10% of people who are responsible for over 75% of the emissions (Rosane 2021). This means it is worth looking at the frequent flyers rather than the average global citizen visiting their family.

Why is there a debate?

People are talking as if we should get rid of the industry, but let’s take a moment to consider the impact this would have. On one hand, the aviation industry has facilitated higher mobility and globalisation. Jobs, tourism, and trade are connected to this mobility and arguably a positive outcome of the industry. The crux of the matter is that aviation is an integrated part of our transportation infrastructure today. On the other hand, before aviation we used shipping and if aviation was limited, presumably shipping would become the crucial means of transportation. This could in many ways still be a solution to more sustainable transportation but at the cost of time. Aviation is a fast solution and shipping would force a shift in demand. Nevertheless, when thinking about sustainability, perhaps removing aviation would slow down capitalistic force and give us reason to reconsider the functions of the market as well as transportation solutions.

The aviation industry is complex. Airports are typically state-owned, yet much of the industry is financially run by private companies. The airplanes themselves are often not owned by the airline company (e.g., EasyJet). Airline companies often lease their airplanes from leasing companies. This is relevant because to change the aviation industry to increase sustainability, we have to look at who facilitates flights in the first place, which in most cases are leasing companies. The leasing companies have power over which airplanes are on the market and the conditions of leasing. With that in mind, imagine the impact if the leasing companies came together and collaborated on a sustainable solution that becomes beneficial to the environment, and hence their business, long term.

Adding to the complexity, the aviation industry is highly globalised and relies on a global network and geopolitical agreements. An example is air traffic management. When aircraft fly from A to B, they have to pass through national airspaces. From a technological perspective, aircraft could easily navigate in a straight line from A to B, but nation-states are forcing aircraft to ‘crisscross’, meaning that aircraft typically fly a distance which is 6-10% longer than necessary due to regulations from nation-states (Dilba 2020). This is absurd from an environmental perspective and could be changed ‘tomorrow’ if the countries agreed; however, they cannot agree—at least not for now.

Aviation routes divert from the most direct route for either economic or practical reasons. Besides air traffic management, this can be caused by factors of wind. When there are headwinds, a flight can take longer, which tends to happen for westbound routes. Aviation routes divert from the most direct route for various economic and practical reasons. Besides air traffic management, this can be caused by factors of wind. When there are headwinds, a flight can take longer, which tends to happen for westbound routes. With technological tools, an algorithm runs the cost of time versus fuel to give a solution. This can be a longer route due to wind directions (Nexteon Technologies 2020). Another factor in flight routes being diverted is closed airspaces. Airspaces can close suddenly and can be caused by natural causes (e.g., eruptions of volcanos) or critical activities threatening safety (e.g. 9/11) (BudgetAir 2022).

The industry relies on cooperation between countries to have a functional business model. Simply put, the state relies on the aviation industry and aviation relies on the state. While we might consider eliminating the industry, it is telling that 93 countries around the world together subsidised aviation with over 200 billion US dollars during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ishka Global). The largest support by region is North America. The countries did so due to aviation being viewed as critical infrastructure. There is not always a feasible alternative to aviation when it comes to global travel, or even local travel between islands or major cities. Yet if we want to be critical, we must ask why the state can subsidise aviation but not supply support and investment for the industry to become more sustainable. Executive Chairman FPG Amentum, Jan Melgaard shares his frustration:

“We need the collaboration with governments to speed up the transition of aviation to net zero.”

—Jan Melgaard, Executive Chairman FPG AmentumAdding fuel to the fire

Governments play an important role in aviation; yet the industry itself is not helping itself. Considering the overall focus on sustainability and green solutions around the world, the marketing used by the aviation industry is often provocative. Adverts for the industry evoke capitalistic values that contradict the focus on environmentally friendly goals, e.g., frequent flyer clubs which aim to enhance customers’ travel activity. Some of the most prominent values associated with flying are exclusive, elite, club, and fun. It comes across as a money machine, promoting luxurious and aspirational lifestyles, and thus it is easy to get frustrated with the entire industry. Frequent flyer clubs are useful to consider because they target passengers flying more than average. These passengers often travel for business purposes and have financial reasons to prioritise time over money. Moreover, the fare attribute company “30K” highlights that frequent flyer passengers are willing to pay 5% more in for fares simply to earn more frequent flyer miles (30k n.d.). Therefore, there is no doubt that frequent flyer clubs entail the wealthier portion of customers and the ones who travel more frequently. This begs the question of whether there is a social contract for environmental issues. Is everyone not obligated to minimise their CO2 footprint? If so, surely a step in the right direction would be that frequent flyers should be taxed one way or the other to compensate for their extraordinary flying activity.

What is the solution?

The aviation industry has been quiet for a long time, too long, regarding sustainable solutions. However, during the last couple of years, there are positive signs. There are various suggestions from the aviation industry itself, including making flight routes more direct or taxing fuel. Nonetheless, there are still bureaucratic obstacles. The basics of taxing aviation fuel have been an ongoing debate and is a complex debate due to the international relations and infrastructure, however, there remain concerns about whether the taxed fuel is contrary to EU agreements and ‘tankering’.1 To change such is and has been a long and slow process. Rather than taxing fuel, there have been solutions to raise money elsewhere to compensate for emissions and contribute to the cost of public services e.g. Air Passenger Duty. Nevertheless, it is not common knowledge to know there is ‘real’ change happening in the aviation industry, although people hope to see improvement, as UCL student Sara states:

“I have a feeling that the technology is being developed but it’s a hard line to walk for the aviation industry because the fossil fuel lobby is going to try to make it not happen.”

—Sara, student at UCLThe solution that would appear most promising long term is using fuels that are produced with electricity from renewable sources such as eFuel (Electrofuel) or PtL (Power-to-Liquid), but this is currently an expensive solution. When solar and wind power were in their infancy in for example, the UK—similar to where eFuel/PtL is today—there was governmental support where a feed-in tariff (FIT) was extended to its development, which has led to it being nearly half of the renewable energy source today. Governmental support can be game changer to green solutions and countries should similarly support the rollout of renewable energy by making eFuel/PtL attainable to the aviation industry. Jan Melgaard explains a country to look for inspiration is the US.

“US government is taking a pro-active approach and the results show already.”

Jan Melgaard, Executive Chairman FPG AmentumWhat would happen if we stopped taking our anger out on the aviation industry for merely existing but instead target our frustration for once again seeing something could be done for a global green transformation with the right political support? This would be the ‘external’ push to a greener solution. However, we can also consider the ‘internal’ movement. The aviation industry has previously faced the challenge of noise, and this was addressed by a combination of regulation and grassroots movements. Perhaps we will see a similar movement in this case, whereby a country will lead the charge using airplanes solely powered by eFuel/PtL.

Conclusion

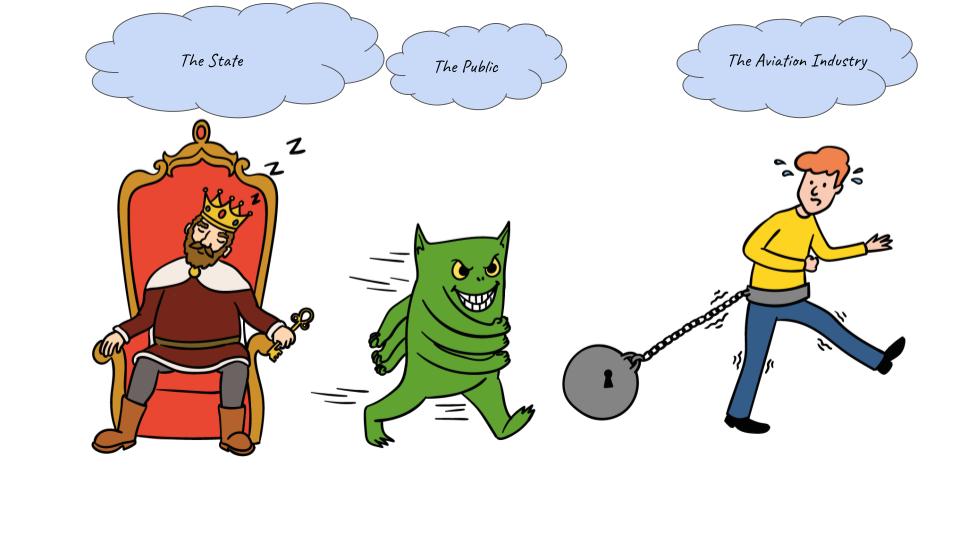

We are understandably looking for someone to blame regarding climate change. However, this is a problematic approach since the problem and its solutions are complex. The state plays a significant role in the aviation industry. Looking at the aviation industry, it is surprising how news media can be poorly informed, and the result is an emotional reaction, which spreads like wildfire. We are allowed to form our own opinion; my point is simply that sometimes the news is simplified to the point that the reaction is missing the point. It can be easier to blame the industry as a large abstract monster, rather than being critical of one’s own daily choices in driving or using takeaway packaging. We need to remember flying is for many an annual decision which cannot be replaced by other means of transportation in regard to economy and time. On a larger scale, tackling the energy crisis requires leadership and bold choice. Unfortunately, individuals, governments, and industries do not feel the direct impact of doing ‘the right thing’.

1 Tankering is when aircrafts carry excess fuel to save fuel cost. The excess fuel leads to extra consumption due to the weight.

Carrington, Damian. (2020) ‘1% of people cause half of global aviation emissions – study’. The Guardian. Dilba, Denis. (2020) How climate-friendly flight routes make air travel greener. MTU AEROREPORT. 30k. (n. d.) Frequent flyer 101. Ritchie, Hannah. (2020) Car, planes, trains: where do CO2 emissions from transport come from?. BudgetAir. (2022) How travel plans are affected by airspace closures. Ishka. (2022) Ishka is a trusted source of data, opinion, analytics, advisory services and events for the Global Aviation Finance Community. Krosofsky, Andrew. (2021) What is flight shaming, and how is it impacting the aviation industry?. Green Matters. Perry, Dominic. (2022) Flight shaming could hamper sustainability investments: Easyjet chief, Flight Global. Flight Global. Seely, A. (2019) Taxing aviation fuel. House Of Commons Library, 523: 1-6. National Air and Space Museum. (n. d.) The evolution of the Commercial Flying Experience. Rosane, Olivia. (2021) Small percentage of frequent flyers are driving global emissions, New Study Shows, EcoWatch. EcoWatch. Transport & Aviation. (n. d.) Subsidies in aviation. Morley, Kate R. (n. d.) National Grid: Live. Srivastav, Sugandha. (2022) The story of solar power in the UK. LSE Business Review. Nexteon Technologies. (2022) Wind — one of five influences in route optimization. Winston, Clifford. (2014) How the Private Sector Can Improve Public Transportation Infrastructure. Brookings, 163-187.