In 2016, I attended the archery World Cup Final, held in Odense, Denmark not long after the Olympics and Paralympics wrapped in Rio. When I was there, I wrote a piece for World Archery about things that people always...

In 2016, I attended the archery World Cup Final, held in Odense, Denmark not long after the Olympics and Paralympics wrapped in Rio. When I was there, I wrote a piece for World Archery about things that people always take with them to tournaments; which brought an interesting range of answers from cuddly toys to beef jerky.

I asked the question (via a helpful translator) to Tan Ya-Ting – twice an Olympian, multiple world and circuit medallist, and a veteran fixture on the Chinese Taipei team. She held out her hands for my camera, showing me two Buddhist temple amulets. She told me the one on the left is from a temple near her house, and it’s supposed to bring safety and security.

The one on the right is from a temple near her best friend’s house, and it’s supposed to bring good results. (Later that day, Tan Ya Ting got knocked out by Ki Bo Bae in the semi-finals, and went on to take bronze.)

Ya Ting was still very much at it at the Taipei Archery Open in December 2022, although she didn’t trouble the higher brackets of the women’s recurve division. But the lady shooting next to her had a similar amulet hanging from her back.

It’s true that many archers, and many elite archers are God-fearing men and women, including some of the sport’s most famous champions. Many bring amulets, talismans, prayer beads, or other religious artefacts with them on tour.

I’ve heard plans and goals qualified with multiple ‘inshallahs‘, and the Christian equivalent from many more. I’ve seen prayers waiting to go on, and prayers on the podium, and thanking the big man on high after slamming in that win, countless times. It’s part of the fabric of international sport, and part of life. But I’ve long been fascinated with the interplay of religion and luck. I was hoping, before I went to Taiwan, that I’d find out a bit more about it. Also, I was hungry. Really hungry.

A few years ago, I wrote an article here called ‘In case you’ve ever wondered where Chinese Taipei is‘, explaining, in very broad-brush detail, why Taiwan is always referred to in sporting and several other contexts as Chinese Taipei. If you don’t know why, I recommend having a read. Or read this, if you want considerably more detail.

A short version: the ‘Chinese Taipei’ pseudonym is carefully negotiated to not really mean anything specific and custom-designed to avoid damaging political rows. Which is why it is absolutely sacrosanct to organisations like the International Olympic Committee. Which is why you will never see the word ‘Taiwan’ in any Olympic context or referring to an Olympic sport like archery, ever.

Once you actually get to Taiwan, it’s a different matter, and you will find that the words ‘Chinese Taipei’ don’t exist – in their English-language press at least. You can delve into the history of modern Taiwan all day. A short version: since the transition to democracy at the end of the 1980s, after decades of brutal military dictatorship, there has been a long, steady and inexorable demographic change in its population towards independence and a distinctly Taiwanese identity.

Many people now see the ‘Chinese Taipei’ fig leaf – negotiated in 1979 to allow Taiwan to take part in Olympic and other international sport – as an embarrassing compromise belonging to another era. There have even been street protests about it, part of the wider (and magnificently named) de-sinicization movement.

In February 2018, a referendum question was proposed that asked if the nation should apply under the name of ‘Taiwan’ for all international sports events, including the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. This bit of sabre-rattling led the East Asian Olympic Committee to revoke the Taiwanese city of Taichung’s rights to host the first East Asian Youth Games. In Lausanne, the IOC was also deeply unhappy and sent three different warnings to the Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee ahead of the referendum vote, making it abundantly clear that they risked being barred from the Olympics.

In the end, the proposal was narrowly rejected: “the main argument for opposing the name change was worrying that Taiwan may lose its Olympic membership under Chinese pressure, which would result in athletes unable to compete in the Olympics.” The Olympics is a big thing here, and the archers are a big part of that thing.

And that’s just our thing. The archery success in Korea has also been mirrored in Taiwan down to the modern structure, with pro teams and corporate sponsorship driving the ultimate goal of international medals on the world stage.

There are many other interesting parallels with modern Taiwan and South Korea; ‘island’ nations (literally or figuratively), both conquered by Japan, reborn after crushing civil wars, suffering decades of dictatorship, and creating economic miracles against the backdrop of powerful communist neighbours. In this century both are hi-tech powerhouses deploying variants of soft power around the world. The difference is, that Taiwan remains only a de facto state, with mainland China consisting and aggressively fending off any and all attempts to make it de jure.

Today Taiwan is a country a sixth the size of Great Britain with a third of the population, almost all crammed onto the western half of the island. Again like South Korea, around two thirds of the country is mountains or uplands. Around a third of the population live in the Taipei metropolitan area. Taiwan has an extraordinary culture all of its own, which has long set sail from its Han Chinese and mainland roots.

So I’m here for archery. Mostly. The instant I am able – about ten minutes after checking into my hotel – I head for the Ningxia night market, which turns out to be a two kilometre wander through dark, dense and oddly European looking streets. Only antique shops are still open by now, along with the ubiquitous 7-Elevens found on almost every corner. Once I finally get there, everything instantly sings of the city, in the rain; the steam, the lights, the beckoning hand art, the smells, the thrum, the energy.

In Britain, street food has become something aspirational and imported, another take of the fabled ‘cafe culture’ that we supposedly yearn for. We even now happily import some versions wholesale to major cities, such as German Christmas markets. It’s exotic and expensive, and often a flex of ‘modern British’ cuisine.

In Taiwan, night markets are strongly associated with religion. Almost all of them – there are around a dozen just in Taipei, depending on definition – are based around temples, serving food and goods for temple-goers. They have become iconic markers of Taiwanese culture in their own right, with their own standards and patterns and etiquette. It helps that Taiwan has a temperate climate almost all year round, and while drizzly and humid, rarely gets cold enough not to allow people to venture outside.

There’s nothing fancy about the night markets. Cheap chairs, strings of lights, gas canisters. The food is relatively simple: each stall usually focuses on one or two dishes only. I am starving. I want to eat pretty much everything everywhere, but decide on grilled squid first. A voracious predator, helplessly spatchcocked onto hot bars, helped to its final fate with a blowtorch.

I can smell it again now; the smoke, the spices from the hoisin and chili barbeque sauce that smothers it, the hint of herbs and the singe of suckers. Eventually, a nice lady chops it for me and adds what tastes like Thai basil and even more hot, orange chilis, and hands it to me. Who are you? You don’t speak Chinese. A shrug. She doesn’t care. No one cares. You’re another punter.

It’s delicious. It hits every beat for grilled marine life and charred flesh and zinging satisfaction. I destroy it in minutes, and move on to some of the more interesting delights; the grilled chicken, and the gua bao bun barely holding on its chunks of sticky pork belly. Feel a greed I’ve not felt for years.

_____________________________

Oh sorry, yes… archery. The next day I am welcomed into the depths of the cavernous NTSU Arena, a gladiatorial multi-purpose sports venue heading back out of the city, back towards the airport, on the almost ridiculously efficient mass transit system. It’s affectionately known as ‘The Burger‘. It’s tidy and clean even if, like quite a lot of things in Taipei, it could do with a lick of paint.

Unlike the vast majority of indoor archery venues it is properly lit, so the archers can see the targets. (You know. The basic stuff.) The organisation is impeccable. We’re also back to masks. Everyone wears masks, all the time, when not shooting. In the arena. In the airport. On the train. In the hotel. Remember that? Remember how that used to be?.

The venue has coffee and judges and archers and people striding around and all the usual. But there’s this slight Lord Of The Flies feel; with the exception of the venue staff and the creaking archery carnies like myself manning stalls and cameras, the average age of the peloton is just twenty years old. There’s an immense youth contingent dragging that average down, but it’s notable just how incredibly young and fresh faced and in-shape everyone is. Healthy young people. Everywhere. Goddamn them all. And organised, into schools and pro teams and sponsors and much more.

The long-planned, but last-minute organisation, on top of some of the longest lasting and strictest COVID immigration rules in the world, means that only a handful of overseas archers have made it to this international event. There’s a few each from Hong Kong, Singapore, India and some others, and just two from Europe – but what a two. Mike and Gaby Schloesser, who I already bumped into at the airport, are very much turning up to win. Gaby asks me what I am doing here. I say I’m here because of the food. She laughs. She thinks I’m joking.

Thank you Ting-Ni. The way to a man’s heart, and all that. In the overly-tableclothed press den suddenly appears some cold pressed tofu flavoured with fivespice and something dark and liquorice-y, plus a preserved ‘iron’ egg, looking like a black plum, thrumming with sweet spice. There’s also some kind of sliced fruit which seems like apple but isn’t quite an apple (or was it?), lightly dusted with cinnamon and maybe something else. I should have asked about this one. But I quite like not spoiling the strange magic. It’s all good. The entry fee includes lunch for all. The lunch is good too; pork and rice and two kinds of salad. You don’t get that at Stoneleigh.

Not all the host nation’s Olympic team are here, with the most notable absence being 2019 World Champion Lei Chien-Ying, doyenne of the international women’s recurve team, and one of the few archers with that presence, who seemed to grow into the role of upsetter she occupied in Den Bosch in those heady pre-pandemic days. She can flex. She can strut. The Svetlana Khorkina of archery. I hope she stays around.

But it’s clear, from the qualification round, that compound men and recurve women are Mike and Gaby’s to lose, respectively. Mikey in particular is in full flow, zero doubts, rattling off the shots, nodding, stomping. It’s all there today.

_________________________

At the end of the day I sneak off on the train to Keelung, the coastal city north-east of Taipei, famous for its night market. This one is supposed to be more tourist friendly, unlike the slightly intimidating Ningxia. It a quiet night under the drizzle, and I don’t see any other tourists – at least, not Western European ones.

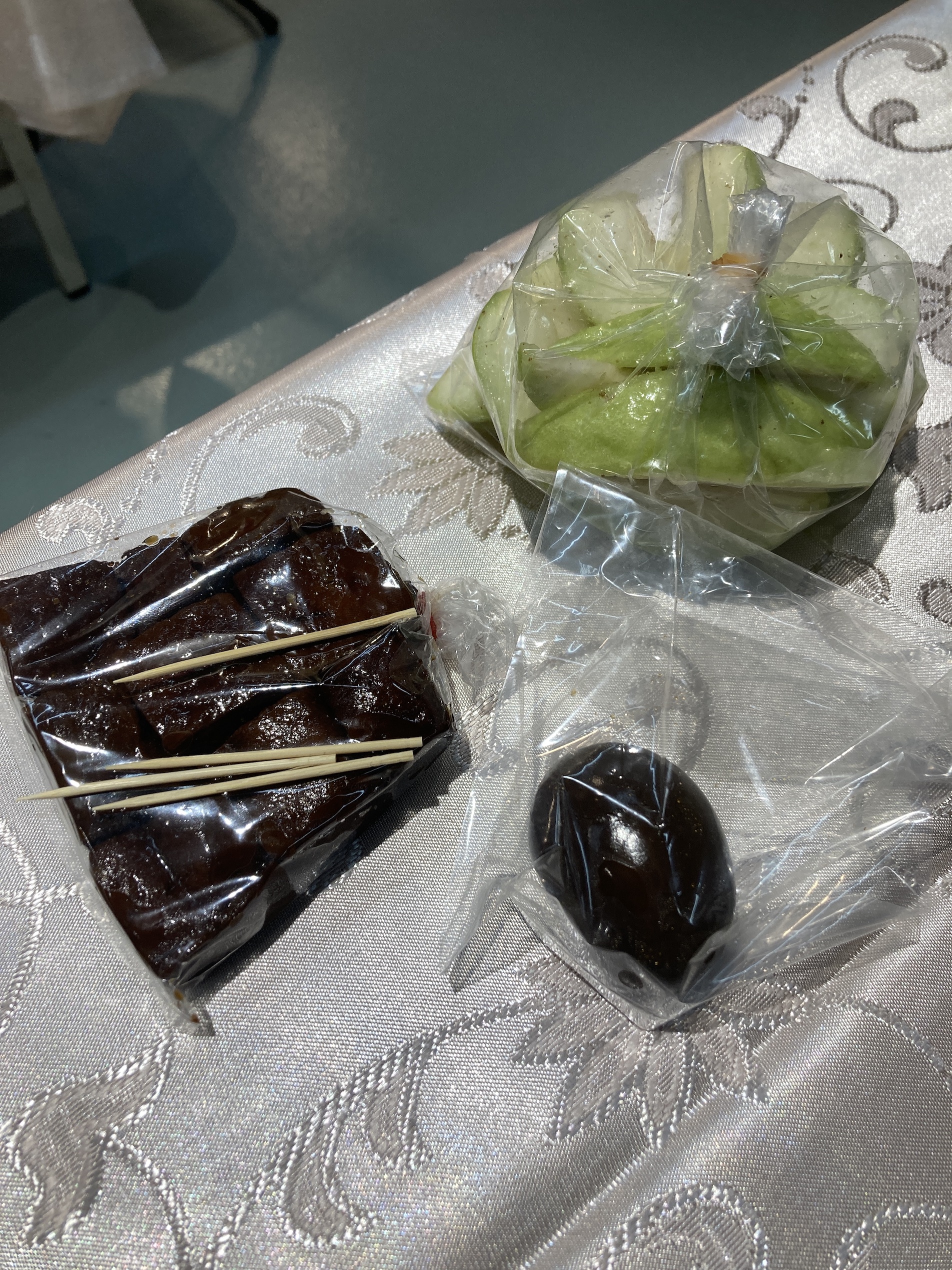

Each stall has its key offering listed in Chinese, English and Japanese. It’s just as well. While younger people here tend to speak at least a tiny bit of English, older people mostly don’t and the miracle that is Google Translate’s camera feature often breaks down into a chaotic and terrifying mess:

Keelung lives up to expectations. The temple in the middle is blocked off and undergoing restoration, and the picturesquely Instagrammable rows of yellow lanterns were turned off this evening. But the food and the atmosphere are still electric, if you can avoid the ever-present scooters piling down tiny streets and through the market itself. Despite the drizzle, there’s a feeling of a bit more depth here, and a slightly tense undercurrent. It’s not for show.

I hit the ground eating. The strangeness and deliciousness of the deep fried tempura fish paste; neither fishy not pasty. First-rate takoyaki, as it should be in a port town; grilled puffs of seasoned batter with a hunk of octopus in the middle, with sweeter and savoury sauces and seasonings scattered along the top. Takoyaki are of course a Japanese street food; part of a wide spectrum of Japanese cultural influences in Taiwan.

Finally, I demolish a greasy bag of tiny ‘one bite’ sausages for a few pence each, thrumming with hot porky goodness, raw garlic scattered alongside.

I can still taste them now. Of course, for me there is an element of exoticism, that Blade Runner mix of Chinese signs and neon and rain and food and so on. But I can feel the heat in my mouth and hear the noise of the market, and sense the slight ennui and the damp and the sea breeze. I can feel my tired feet walking back to the station and the chill of the boardwalk. I’m still there, if I want to be.

__________________________

It’s abundantly clear that Taipei is a fully functioning city, at least if it’s judged by its mass transit system, which is abundant, clean, helpfully signed, and (crucially) with clean toilets in every single station. I am starting to judge ‘major world city’ status by this last metric. Can any city which doesn’t have usable toilets in every station be even classed as fully functioning? If you’ve ever tried to take an elderly relative on a day around London, you may have an answer to that question.

even the keeping people honest posters have a spiritual dimension

even the keeping people honest posters have a spiritual dimensionOf course, the immense Taipei metro system doubles up as an air raid shelter that can apparently hold the entire population of the city, just in case there is ever some kind of… incident. Clean toilets and exceptional food available all evening. That’s not much to ask, really, is it?

Oh sorry, yes… archery. It turns out to be well worth waiting for. The long day of finals on Sunday winds on into the senior competition in the evening, all broadcast in 8k virtual reality. The Schloessers stay calm and collected and take their wins. Mike’s opponent in the gold match, the 24 year-old Chen Chieh-Lin had put in a 149 in the 1/8 round, but seemed tense and nervous on the stage, and quickly fell away. Against a on-point Mike in full flow, there was no coming back. It got to the point where a single nine from Mike, barely outside the ring, drew a gasp from the audience. But it was barely even a blip.

Ten minutes later, Gaby takes the stage against Shilin Liu of Chinese Taipei, who had shot consistently if unremarkably to make the final. Schloesser, who had pounded the Dutch national record into smithereens in qualification, hadn’t dropped a match point until the semi, when she was pushed a little by Fan Wang-Ting of the host nation, who went on to take bronze.

With a loping, elegant draw, Liu stepped up to the plate, looking the least nervous of the host finalists by far. It wasn’t enough. Not even close. Schloesser(s) scorched earth again. Mike and Gaby, against jet lag and the best one of the biggest Asian archery nations can throw at them, have performed brilliantly. They both look exhausted. It’s tough at the top. And full marks to Wei Chun Heng. An inaugural champion, and a stand up guy.

____________________________________________

The competition wrapped, I head off to Raohe night market, attached to the Songshan Ciyou temple, a Daoist landmark. To call temples in Taiwan ‘ornate’ is understating the issue somewhat; in what might be considered a competitive religious market, temples pile dragon upon dragon, turret upon roof, and wild detail upon all.

While the Ciyou temple is Daoist in focus, dedicated to the goddess Matsu, in practice most temples have a kind of syncretic approach combining Buddhism, Daoism, and Chinese folk religion. There is also a temple here dedicated to Confucius, in a country where Confucianism hovers between philosophy and religion. (Reading about the Three Teachings may be useful here). There are also syncretic creeds aiming to unite all.

In short, religious freedom has lent Taipei a colourful atmosphere, and contrasts sharply with mainland China, where the Cultural Revolution saw folk religion almost hounded out of existence.

It’s also an extraordinarily religious place overall. The whole country has 12,000 temples, with 700 in Taipei alone. As my very handy Insight Guides app tells me: “Traditional customs, beliefs, icons, and old superstitions permeate all levels of society in Taipei. Most adults – even those who may not profess a particular religion – routinely worship at a church or temple, and engage in spiritual activity.” That doesn’t include nearly 4000 Christian churches across the island as well.

It appears that communing with the divine in Taiwan has something of a pragmatic, transactional approach. You can visit a temple to ask a particular god for divine assistance, but you must express gratitude by lighting incense, burning paper money, and other offerings. You may also ask questions using jiaobei, or wooden ‘moon blocks’. Large bins of them are available in temples. The way the blocks fall, when thrown to the ground, will give you the answer you seek, or indicate the pleasure or displeasure of whoever you decided to ask. In the smoke and the gloom, you may find what you are looking for.

Barely steps from the temple door is Raohe Night Market, serving all who worship and all who seek answers. Crammed tightly down a narrow street, it’s a swirling riot of colour and smell and ringing bowls and gaudy midway barking. The will-I-or-won’t-I of a visit to the temple is mirrored here, with carnival games of chance; bagatelle, pachinko, for prizes or more. Fortune teller booths line each side; it seems to mostly be a profession for older gentlemen. You can go fishing. Buy clothes. Play games. Gamble. And eat all kinds of terrifying and wondrous food.

There’s a few things I want to try, but I head straight for the stall doing black pepper rolls. Several of the night market stalls have managed to make it into the no-doubt-utterly-insufferable Bib Gourmand, including this one. (Sixty bucks is about £1.60). It’s a bun, filled with lightly spiced pork and cooked in a tandoor-style oven.

The meat is interesting, softly spiced, but not the highlight. The miracle was the delicious bread which somehow managed to be soft, crisp and a bit flaky at the same time, with the lovely little burned bits that add something to a proper pizza crust. It’s meat and bread. But it’s somehow completely unique. I want to scoff twenty of them.

I’m used to cities, even though I don’t live in one anymore. I like to think I understand them. But there’s something markedly different about Taipei. For all its Western trappings, there seems to be something else; a sense of caring, of welcoming other influences, a sense of moving with the world rather than against it. Maybe that’s Daoism in action.

________________________________

Monday is my last day. I want to wander, but many things are closed, and my legs and body are tired. I go to look at a few things, but eventually just decided to pause and sit at Xingtian Temple, one of the ‘new builds’ from the 1960s, and dedicated to some rather authoritarian-sounding god, which doesn’t sound very Daoist to me, but I’m new at this game. It’s now something I try to do in any new place; find a spot where something is happening, and just sit and listen and watch; be aware, absorb. Sit by the flow. Your thoughts wander. You try to bring them back.

For all the dragons and paint, the carvings and the incense, the temples are pretty simple buildings. This one, on a workday lunchtime, is fuller than any church in Britain or Europe that I’ve ever seen. It at least seems to celebrate the congregants rather than the landowners. Line up and be blessed. Rattle your jiaobei. Bow your head, together. Be part of it.

There is a book called Keeping Together In Time by the American historian William H McNeill, which argues that synchronised movement (and also singing) is a underappreciated force in human history; fostering cohesion amongst groups. You see it here, as you see it many places, the collective nod. I find myself joining in. I can’t not.

I also start thinking about archery. On the field, as in the temple, you join in together, and you wish for luck. That this time, you will bring the best of your ability. This time, the magic will not leave you. We all know that it is a sport in which you make your own luck, but the variance, especially at the very highest level, is the unkindest cut of all. It sometimes feels like you have upset a deity somewhere.

It’s always bloody archery, the sport that glaringly reflects your life back at you. You go through the ritual. You put on your robes, you make everything ready. You light the metaphorical incense. What are the bones going to reveal today? No wonder it is a sport for the God-fearing. Sometimes, the truth is just too hard.

Special thanks to Ting-Ni Chen for all her help.

The post 2022 Taipei Archery Open appeared first on The Infinite Curve.