I’m very pleased to feature a new post from Jill Stewart, the first of a three-part series. Jill is Associate …Continue reading ?

I’m very pleased to feature a new post from Jill Stewart, the first of a three-part series. Jill is Associate Professor in Public Health at the University of Greenwich and has worked in housing for over 30 years. She has written previously for Municipal Dreams about the earliest environmental health practitioners before 1914 and after the First World War and on the South Oxhey Estate. This is my review of one of Jill’s books, Environmental Health and Housing: Issues for Public Health.

You can follow Jill on social media @Jill_L_Stewart and @housing-jill.bsky.social and see more of her work on her personal website, Housing, Health, Creativity.

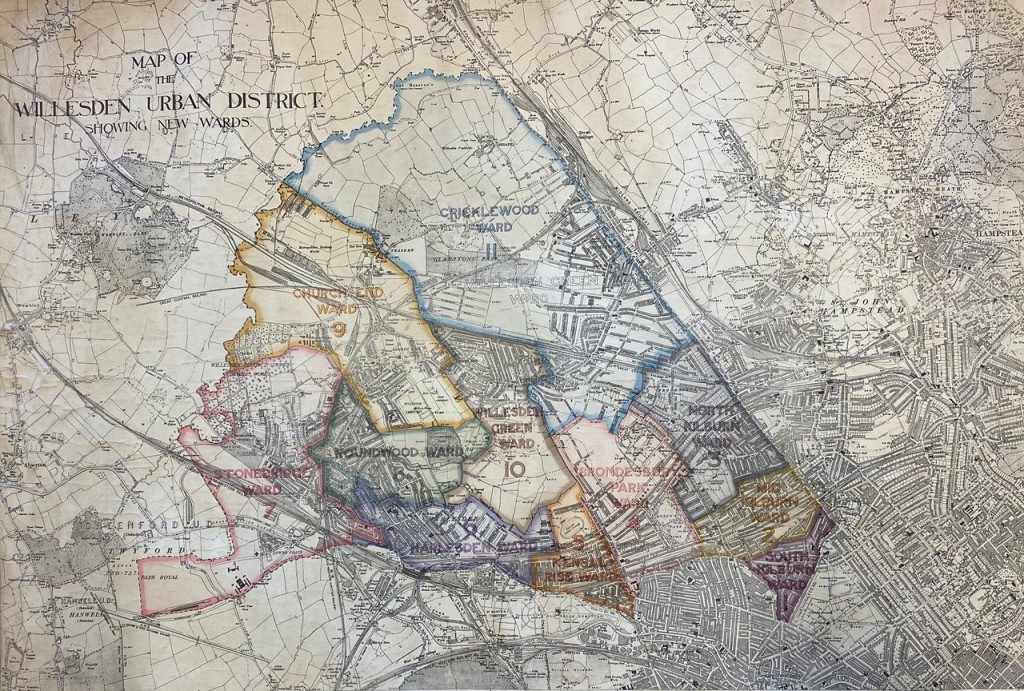

Visiting Stonebridge Park, NW10, today, in the urban London Borough of Brent, it’s hard to imagine that its first council housing was planned on an old sewage works on open space that the North Circular Road now cuts through (see figure 1 from 1908). Some will know Stonebridge Park as being near Wembley and Harlesden, or as the area between the popular Ace Café and the astonishing Neasden Temple. Others may know it from the news and reported levels of crime. But for many, it was the place they called home for many years in a close-knit community of families and friends, each a part of its dynamic history, experiencing a range of housing conditions and tenures over a century that we are looking at in this post.

Figure 1: Board of Guardians Map of Willesden Urban District, by O Claude Robson, 1908. With permission of London Metropolitan Archives, City of London. Document reference London Metropolitan Archives, City of London, BG/W/133

Figure 1: Board of Guardians Map of Willesden Urban District, by O Claude Robson, 1908. With permission of London Metropolitan Archives, City of London. Document reference London Metropolitan Archives, City of London, BG/W/133

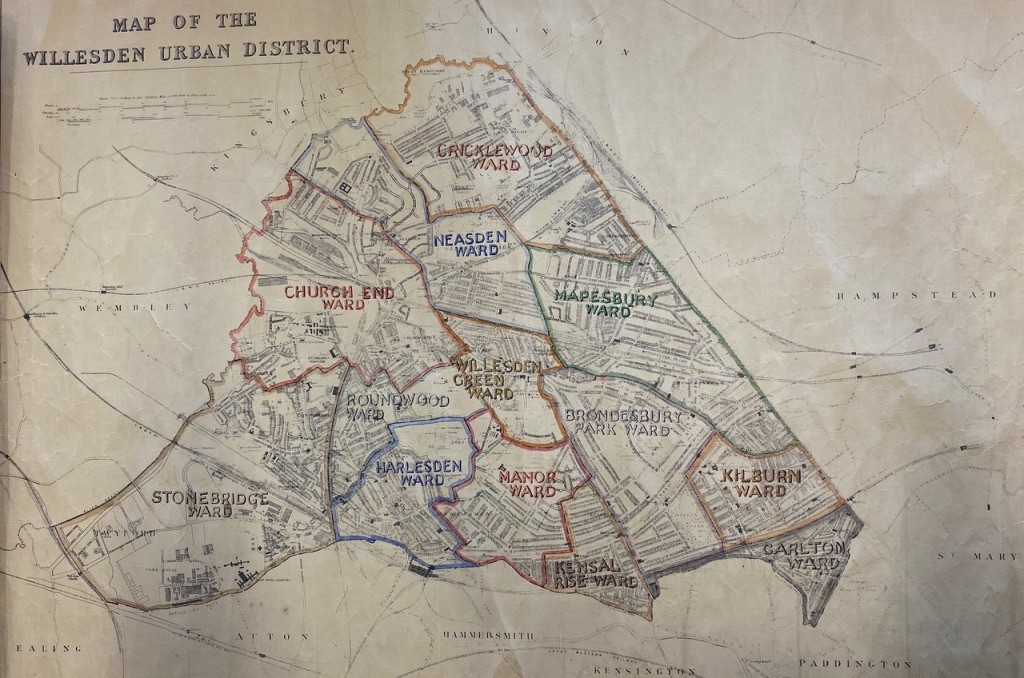

Situated near Wembley and sandwiched between Stonebridge Park and Harlesden stations, Stonebridge Park is spread across each side of the Harrow Road and Hillside. Some refer to it as Harlesden, but it is not. Once part of Middlesex County in the largely Labour controlled Willesden Borough (fig 2), Stonebridge came to comprise one of the then newly formed London Borough of Brent’s largest council housing estates, along with South Kilburn and Chalkhill, the latter in the then Borough of Wembley (1).

Fig 2: Map of Willesden Urban District, showing the Brentfield estate, undated but probably 1920s by F. Wilkinson, Borough Engineer (note he also authored the document included in reference 6 below).

Fig 2: Map of Willesden Urban District, showing the Brentfield estate, undated but probably 1920s by F. Wilkinson, Borough Engineer (note he also authored the document included in reference 6 below).With permission of London Metropolitan Archives, City of London. Document reference London Metropolitan Archives, City of London, BG/W/136.

What is surprising now for those who know this busy urban setting is that in the late 19th century plans for the area were for it to be a setting for large villas. Indeed, some of these properties remain as reminders and a nod to this past and journey that Stonebridge Park may otherwise have taken. But that was not to be. All that remains now of these large properties is the Stonebridge Park Hotel (now The Bridge) along Hillside (Fig 3) and the Italianate inspired villa Altamira 1876 (Fig 2) that at the time of writing (spring/summer 2023) looks set for demolition (2). These heritage features added – and continue to add importance – aspects of identity to the area and many are sad to see them under threat.

Fig 3: The Stonebridge Park, now Bridge Hotel. Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Fig 3: The Stonebridge Park, now Bridge Hotel. Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Fig 4 The Altamira built 1876. Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Fig 4 The Altamira built 1876. Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Any history of housing is also a history of health, perhaps most explicitly when council housing is involved. This post develops the earlier Municipal Dreams posts of Tackling the Slums 1848-1914 and 1914-1939, but here we focus on Stonebridge Park’s council housing from just after the First World War to the present day. The Medical Officers of Health, then in local councils, worked closely with Sanitary Inspectors, later called Public Health Inspectors (now known as Environmental Health Officers or Practitioners) to address poor housing conditions. The links between housing and health were well established into council house building by the Housing and Planning Act 1919 (also known as the Addison Act), Dr Christopher Addison being the first Minister of Health and Housing.

I am going to try to tell Stonebridge Park’s unique history using archives, personal knowledge, photographs and films. There are really three phases in the history of Stonebridge Park’s council housing. First, a slightly delayed effort at Homes for Heroes (properly termed ‘a land fit for heroes to live in’) after the First World War. Next, a lag after the Second World War and into the world of substantial clearance and redevelopment and new tower blocks. Next, a new and more recent approach delivered by a Housing Action Trust and beyond that, to the Stonebridge Park that exists today. Whilst this is a local history, it will have resonance to many interested in housing history more widely.

A land fit for heroes to live in

Plans had already been afoot in 1914 to house Willesden’s working classes but there were delays and then the onset of War. They were held in abeyance until the Housing and Planning Act 1919 (the Addison Act). In 1917 the Local Government Board requested that Willesden make land available for housing and council owned land at Stonebridge was selected, using the ancient name of Brentfield. Plans were submitted to the Minister for Health in January 1919 but amended in June 1919 due to plans for the North Circular Road. Following various delays and new proposals between the Ministry and Housing Committee of the Council, plans were finally adopted in January and contracts for building signed in May 1920 (3, 4, 5, 6). See Figs 3 and 4.

Fig 5: Willesden Urban District Council Brentfield Housing Scheme Booklet, June 1921, front cover. Reproduced by kind permission of Brent Museum and Archives (Reference 6).

Fig 5: Willesden Urban District Council Brentfield Housing Scheme Booklet, June 1921, front cover. Reproduced by kind permission of Brent Museum and Archives (Reference 6).

Fig 6: Willesden Urban District Council Brentfield Housing Scheme Booklet, June 1921, parlour house designs. Reproduced by kind permission of Brent Museum and Archives (Reference 6)

Fig 6: Willesden Urban District Council Brentfield Housing Scheme Booklet, June 1921, parlour house designs. Reproduced by kind permission of Brent Museum and Archives (Reference 6)

The Opening Ceremony was reported in the Willesden Chronicle (5) attended by Council representatives, new families in residence and children singing and enjoying the event. Speeches referred to families having a ‘home and the centre of family life … a fair chance … free from the interference of other people’ and mentioned that ‘all tenants had their own drying ground and their own copper’. The article added: ‘the people of Willesden would feel that they had something on this historic spot that had been worth creating and worth preserving’.

These Addison houses were part of the drive for a land fit for heroes to live in after the war. The report tells us about the new housing but not what it must have meant for those who were to be housed there. Many residents in the then Borough of Willesden, in places including Kensal Green, had endured some really poor and overcrowded accommodation over a substantial period of time. For one family who were to later move to the Brentfield estate, poor housing conditions in other parts of Willesden were at least in part responsible for the loss of six of their children to disease including premature birth, debility and bronchitis.

It was cases like this that had kept the Medical Officer of Health for Willesden (MoH) very busy and much can be gleaned from their annual reports about housing and health. In the 1919 report, the MoH wrote that the staff engaged with housing work in the Health Department included one Chief Sanitary Inspector and six District Sanitary Inspectors and one Clerk, who had issued orders for repairs, voluntary closures and closing orders in the general Willesden area (7).

Fig 7: Conduit Way and Wyborne Way, Stonebridge, looking toward the North Circular Road, with the Wembley Stadium arch in the background. Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Fig 7: Conduit Way and Wyborne Way, Stonebridge, looking toward the North Circular Road, with the Wembley Stadium arch in the background. Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Fig 8: Sunny Crescent, with green open space. Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Fig 8: Sunny Crescent, with green open space. Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Brent Junction and housing off the North Circular Road, Stonebridge, from the south-west, 1932. (Image taken from a damaged negative) © Britain from Above, EPW038700

Brent Junction and housing off the North Circular Road, Stonebridge, from the south-west, 1932. (Image taken from a damaged negative) © Britain from Above, EPW038700

The municipal Stonebridge Health Centre, on the Harrow Road, was opened on 8th April 1930 by the Rt. Hon. Arthur Greenwood and was described as one of the few centres nationally to be specifically designed, built and equipped for modern health work, with a focus on maternity, child welfare and school medical work. It also offered an Artificial Sunlight Clinic and Orthopaedic Clinic (8). Arthur Greenwood had served as Labour’s Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health in 1924 and was appointed Minister of Health in 1929, later becoming Deputy Prime Minister under Clement Attlee.

Even by 1933, Willesden’s MoH (10) had singled out several roads in Stonebridge (and nearby Kensal Green) as requiring intervention. These comprised some 1036 properties housing 9297 persons: Carlyle Avenue, Milton Avenue, Shakespeare Road, Shelley Road, Shrewsbury Road, Melville Road, Winchelsea Road, Mordaunt Road, Wesley Road, Brett Road, Barry Road, Denton Road (see 10) and Hillside from Shrewsbury Road to Denton Road. The report went on say: ‘It is not easy to give an estimate of the amount of overcrowding in these areas but it is not inconsiderable, and houses would be required to be provided for persons displaced from such areas.’ (Please remember these addresses; we will come back to some of them in the 1970s, but the point to emphasise now is the immense amount of time households lived in known poor and overcrowded conditions, around 40 more years.)

Fig 10: Medical Officer of Health Willesden Report 1933: 106 (9): Source Wellcome Library, London’s Pulse: Medical Officer of Health reports 1848-1972 and reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

Fig 10: Medical Officer of Health Willesden Report 1933: 106 (9): Source Wellcome Library, London’s Pulse: Medical Officer of Health reports 1848-1972 and reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

It is not quite clear what happened during the 1930s but as the world moved toward war, housing at Stonebridge seemed to be on the back burner, despite the immense challenges faced.

Post-World War Two in the Borough of Willesden: housing loss and renewed progress

Both the MoH wartime and post-war reports reveal the extent to which Stonebridge suffered bombing during the Second World War (11). In 1944 the MoH referred to the ‘renewal of hostile activity and the re-evacuation of residents and their families from the area’ and the damage to the Willesden Green and Stonebridge Health Centres. Being next to Harlesden, Park Royal and so many factories including Heinz and McVities, Stonebridge Park endured substantial bombing and V2 raids. The 1948 MoH report (12) reveals that 92 homes were destroyed by bombing in Stonebridge Park, some locations are shown on the Bomb Sight map below.

Fig 11: from Bomb Sight of Stonebridge 1940-41 (version 1.0, 28 June 2023)

Fig 11: from Bomb Sight of Stonebridge 1940-41 (version 1.0, 28 June 2023)

The MoH report for 1949 continued to emphasise the effects of the war and poor housing conditions on the population, with ‘mixed populations with bad, almost slum property in Church End and Stonebridge …’ (13, p.6). The 1950 report (14) focused on tuberculosis, recognising the environmental conditions and overcrowding in places like Stonebridge contributing to the highest levels in the borough. By 1951 the MoH said: ‘Since the treatment of tuberculosis is very costly, not only in medical treatment but also in production and in lives, it is much more economical in the long run to spend the money on improving housing and nutrition and thus preventing the disease’ (15, p.13). As people continued to move into the area in the early 1950s, the MoH (16) reported increased overcrowding and home accidents amongst lower income households and called for better housing to conquer tuberculosis.

With the war having diverted attention from housing interventions and renewal, existing housing falling into greater disrepair and overcrowding due to the scarcity of building supplies and builders, conditions had deteriorated further. Bernard Shaw House was built around 1951 (Fig 11) but housing need remained acute. But it wasn’t just housing policy that was changing, there were far wider socio-economic challenges on the horizon. Industry was in decline and unemployment on the increase, youth culture was in ascendance, and tensions in race relations provided an emerging backdrop to what was to happen next.

Fig 12: Bernard Shaw House, probably built around 1951, Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

Fig 12: Bernard Shaw House, probably built around 1951, Photograph ©Jill Stewart 2023

References

(1) Stewart, J. and Rhoden, M. (2003) ‘A review of social housing regeneration in the London Borough of Brent’, The Journal of The Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 123 (1), pp.23-32

(2) Willesden Local History Society, Stonebridge

(3) Brent Museum and Archives, History of Stonebridge

(4) Brent Museum and Archives, Homes For Heroes – Willesden Council’s Brentfield Housing Scheme

(5) ‘Willesden’s Municipal Houses’, Willesden Chronicle No. 2302, 17 June 1921, p.6

(6) ‘Willesden Urban District Council Brentfield Housing Scheme Booklet’, by F. Wilkinson, Engineer to the Council, 11th June 1921

(7) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report, 1919

(8) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report, 1930: p.20 and 24

(9) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report, 1933: p.106

(10) Jill Stewart, Denton Road, Stonebridge Park, NW10 – Housing Health Creativity

(11) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report 1944

(12) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report 1948

(13) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report 1949

(14) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report 1950

(15) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report 1951

(16) Medical Officer of Health for Willesden Report 1952

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the National Archives (for background reading and resources not cited here), the London Metropolitan Archive, the Brent Archives, and the Wellcome Library for its online collection of Medical Officer of Health reports.