Receiving and unpacking acquisitions can be an exciting but also a nervous moment for a gallery conservator. This is the first opportunity to catch a glimpse of the artwork you have heard so much about from your colleagues, but...

Receiving and unpacking acquisitions can be an exciting but also a nervous moment for a gallery conservator. This is the first opportunity to catch a glimpse of the artwork you have heard so much about from your colleagues, but you are also well aware of the risks involved with transporting artworks, and this is the moment where any misfortunes that have occurred along the way will be revealed.

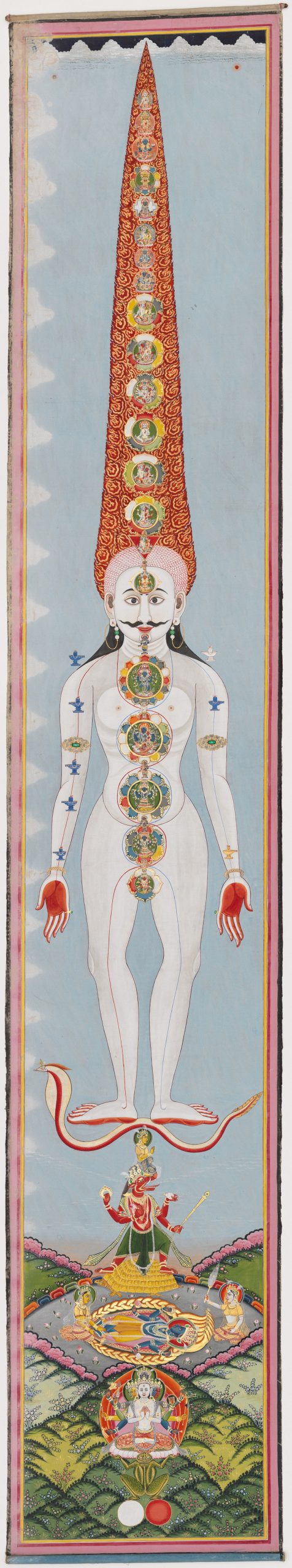

This was the case with the Asian art collection, a 19th century Nepalese scroll painting. We cautiously unwrapped the framed artwork only to discover that its mounting system had failed, fortunately it suffered no permanent damage, however, required some conservation work before it could be first shown in 2012. Back on display, you can now view Untitled (Chakraman) at the Queensland Art Gallery until 23 June 2024 during the exhibition ‘I can spin skies’.

ARTWORK STORIES: Delve into QAGOMA’s Collection highlights for a rich exploration of the work and its creator

ARTISTS & ARTWORKS: Explore the QAGOMA Collection

What went wrong with the mounting system? When I opened the frame I discovered the scroll had been stuck down directly to a board using both silicon adhesive and double-sided sticky tape. The board’s paper covering had ripped with the weight of the scroll, leaving both adhesive and paper residues attached to the back of the artwork. The adhesives remained firmly attached to the back of the artwork and didn’t want to release their grip.

Old adhesive and paper residues on the back of Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

Old adhesive and paper residues on the back of Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

All residues of these non-archival adhesives needed to be removed before they could leave lasting stains on the artwork. The artwork had to be turned face-down in order to do this, so any loose paint fragments on the front needed to be secured first. Although it is in very good condition considering its age, there are some cracks and small areas of missing paint along the edges, with some loose paint fragments in these areas.

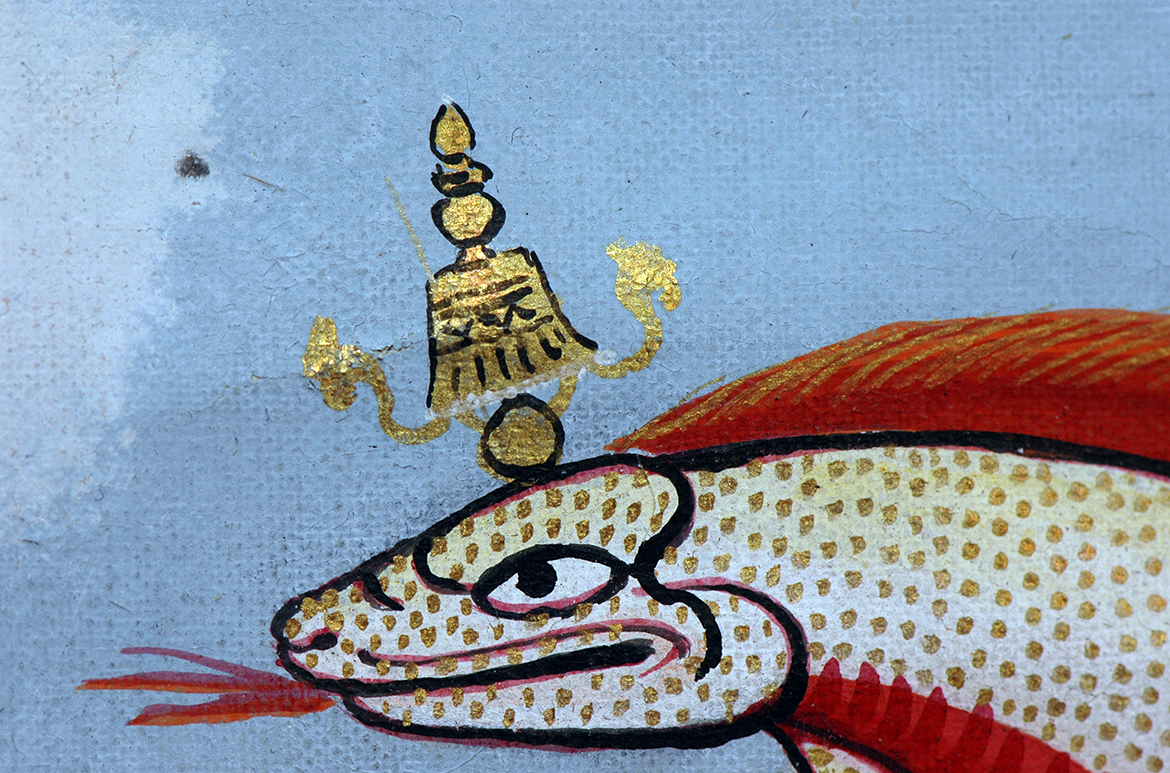

Fine cracking and small loss to the paint layer of Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

Fine cracking and small loss to the paint layer of Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

I tested different adhesives to determine what would best hold the fragments in place, and not cause staining to the surface. Eventually I chose methylcellulose, which is a polymeric substance widely used in the food and cosmetics industries as a thickener and emulsifier. Conservators sometimes use it as a mild adhesive, as it is easily reversible in water and has good ageing properties. In this case it was strong enough in a low concentration to hold down these tiny flakes but viscous enough not to flow into the surrounding area and cause staining. I applied it with a fine brush into areas of loose paint, then weighted and left the areas to dry.

Applying adhesive to areas of loose paint on Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

Applying adhesive to areas of loose paint on Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

Once the loose paint fragments had been secured at the front, the artwork could be safely turned over, and the adhesive-removal could begin on the back. This was a painstakingly slow process using various surgical tools (such as fine tweezers and a micro spatula) to pry the adhesive residues away from the artwork without leaving a mark.

Gradually removing old adhesive and paper residues from the top edge of of Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

Gradually removing old adhesive and paper residues from the top edge of of Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

Some help came from solvent vapours, which when carefully applied using a mini vapour-chamber softened the double-sided sticky tape. Solvent-soaked cotton wool is held securely in the top of a glass chamber. This is then placed over the residual sticky-tape for 2-3 minutes. The solvent vapours don’t have enough time to cause any damage to the artwork but soften the sticky-tape just enough to help remove it.

With the removal of one mounting system a superior solution had to be devised. The artwork was originally designed to hang by its top bamboo rod, but this would place the strain of the artwork’s weight on the top seam holding the rod. Although the seam appears strong enough to take the strain at the moment, over time gradual weakening and deterioration is likely. Instead I added a new hanging system to the back of the artwork. This comprises a new ‘hinge’ of fabric made from stable, inert materials and adhered to the back of the artwork near the top edge with a reversible heat-set adhesive.

The new hinge spreads the weight evenly through the top edge once Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century is suspended by it.

The new hinge spreads the weight evenly through the top edge once Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century is suspended by it.

I attached the other end of the hinge to a backing board, so now the artwork hangs suspended from this hinge, distributing the weight more evenly through the cotton support. The bamboo rods have been secured against movement by tying their ends down to the backing board. Finally the artwork and backing board have been enclosed in a protective perspex case for display.

Conserving Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

Conserving Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century

Unknown / Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century / Distemper on cotton / 293 x 51.5cm / Purchased 2010 with funds from the Henry and Amanda Bartlett Trust through the QAG Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

Unknown / Untitled (Chakraman) late 19th century / Distemper on cotton / 293 x 51.5cm / Purchased 2010 with funds from the Henry and Amanda Bartlett Trust through the QAG Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

Jocelyn Evans is former Paintings Conservator, QAGOMA

‘I can spin skies’ is in the Queensland Art Gallery’s Henry and Amanda Bartlett Galleries (5&6) from 5 August 2023 until 23 June 2024.

#QAGOMA