Foto/Industria examines specific aspects of the relationship between games and industry, investigating the implications and repercussions in the fields of psychology, architecture, economics, history, ecology, politics, and even the deepest drives of the human soul

It’s already the third edition of Foto/Industria -the biennial of photography that documents industry and work- that i attend (the previous ones were dedicated to food and to the technosphere.) And yet, it feels like the tourist in me will never get tired of walking around the city of Bologna to visit the exhibitions located in various palazzi and museums.

Andreas Gursky, Toys “R” Us, 1999

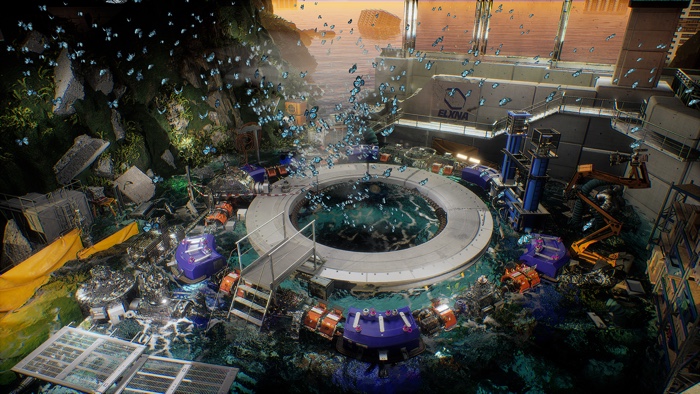

Mattia Dagani Rio, Los Santos, 2023. Part of Automated Photography, an exhibition based on a research project of the Master of Photography programme at ECAL/University of Art and Design Lausanne

Exhibition view of Automated Photography. Photo: ECAL/Taje Giotto Mahalia

This year’s Foto/Industria explores the theme of ‘game’ and in particular the production of objects, devices and emotions engineered by a sector that is constantly reinventing itself and is notoriously receptive to technological innovation.

The scope of this investigation into the relationship between games and industry is very (very) broad. There are photos of a real-life Monopoly, playgrounds, video games, funfairs and Las Vegas slot machines but also works that probe into the implications of games in the fields of psychology, architecture, finance, history, ecology and politics. The result is full of joy and ambiguity.

Here are some of the shows I enjoyed the most:

Danielle Udogaranya, Mind Games, 2023. From the exhibition Seeing You, Seeing Us

Danielle Udogaranya, Eden, 2023. From the exhibition Seeing You, Seeing Us

Danielle Udogaranya, aka Ebonix, is showing a collection of digital avatars she made for The Sims. Frustrated not to see herself nor her community reflected in life simulation video games, the artist has been teaching herself 3D modelling. Her objective was to give an identity and visibility to people who are often excluded or neglected by game developers and by society in general. Her work particularly focuses on recreating the full spectrum of black hair, which she calls a defining feature of black culture. Black hair has many textures, styles, types of braiding and dos that were so far not seen on virtual characters.

Combining design, gaming and activism, her series acts as a call to developers and the gaming industry in general. If a self-taught 3D modeller like her could help so many players recognise themselves in the game, what is the industry’s excuse for not making diversity one of their priorities?

Ce?cile B. Evans, Reality Or Not, 2023

Ce?cile B. Evans, Reality Or Not, 2023

Ce?cile B. Evans, Reality Or Not, 2023

Ce?cile B. Evans, Reality Or Not, 2023

Ce?cile B. Evans, Reality Or Not, 2023

Ce?cile B. Evans, Reality Or Not, 2023. Exhibition view at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna

Reality Or Not follows a group of students from a high school located in the suburbs of Paris who are invited to take part in a new type of reality show. Along with the students, the main characters are generated using a video game graphic engine. They are “a statue that is curious about its status as a symbol, a Real Housewife of Algiers from the future — who is also a helper and a medium and who aims to take down the president of the International Monetary Fund — and a workers collective of renders of failed versions of a virtual influencer”.

The show is an experiment. Its premise is that the young women are invited to collectively appropriate and modify the reality around them. By playing with visual codes and constantly jumping from one reality to the other, the film is both seducing and disorientating. What is real? What is virtual? What is fiction? When are the protagonists being themselves and when are they playing with the film director, the audience and each other? I’m not sure i understood everything but i absolutely loved that work.

A model of the house featured in the film and several mock-ups for the characters accompany the video.

Olivo Barbieri, Flippers, 1977-78

Olivo Barbieri, Flippers, 1977-78

Olivo Barbieri, Flippers, 1977-78

Entrance to the exhibitions Olivo Barbieri, Flippers and Daniel Faust, Las Vegas at Musei Civici Bologna / Museo Civico Archeologico

In 1977, Olivo Barbieri discovered an abandoned pinball machine warehouse and photographed it from a variety of angles and perspectives for two years. For the photographer, the machines act as relics of future archaeology. They bear witness to the culture, aesthetics and fantasies of a time that now looks almost alien to us. The scenes painted on the pinball machines belong to a bygone era, to a time characterised by economic boom, faith in progress, space travels and limitless admiration for the U.S. culture.

Daniel Faust, Las Vegas, 1997

Barbieri’s photos are exhibited at the Archaeological Civic Museum of Bologna. Just like the ones that Daniel Faust shot in Las Vegas. They seem to talk to one another. It’s the same vintage vision of entertainment, joy and modernity. The same ideal of U.S.A., one that is yellowing and fading under the pressure of contemporary realities.

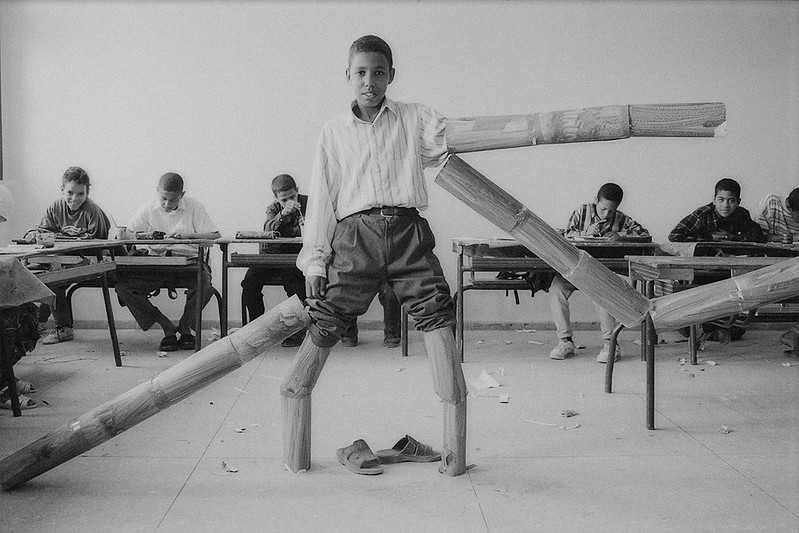

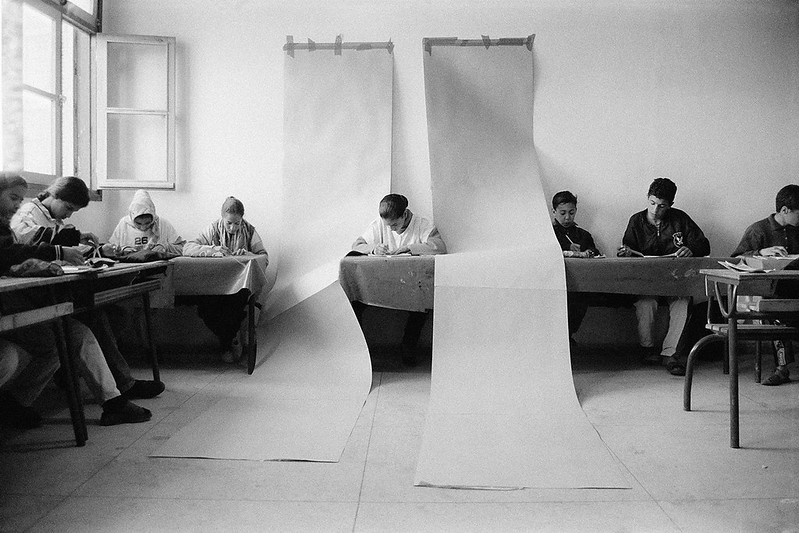

Hicham Benohoud, La salle de classe, 1994-2002

Hicham Benohoud, La salle de classe, 1994-2002

Hicham Benohoud, La salle de classe, 1994-2002

Hicham Benohoud, La salle de classe, 1994-2002

Hicham Benohoud was an art teacher in Marrakech when he started working on his project La Salle de Classe (The Classroom.) Bored to just sit at his desk while his students were drawing, painting and cutting, he had the idea of transforming the classroom space into a photography studio. The students became his models. He gave them props, suggested poses and gestures, bridled their limbs or simply let them work as he modified the space around them. By staging their positions and gestures, Benohoud used the young people as puppets. Turned into “living sculptures”, the students enact power relations between young individuals and educational institutions. It’s not clear how comfortable the students were during these sessions. How much agency they had on their teacher’s game. Or how much Benohoud was using his authority to get the students to transgress the rules of the classroom.

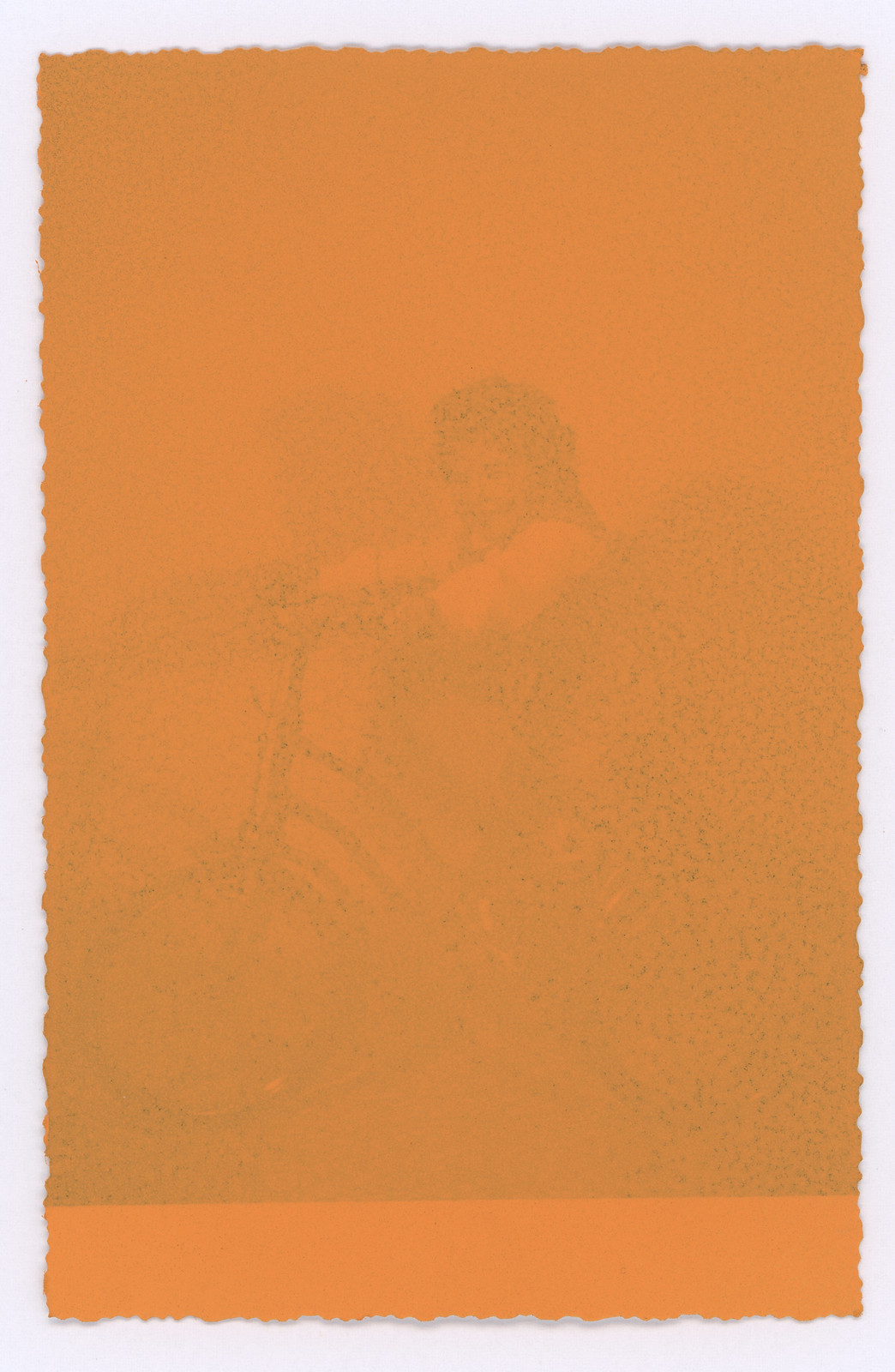

Read Yassin, Karaoke, 2015. From the exhibition Ghost Karaoke

Read Yassin, The Company of Silver Spectres, 2021. From the exhibition Ghost Karaoke

Read Yassin, The Company of Silver Spectres, 2021. From the exhibition Ghost Karaoke

I loved Raed Yassin’s show at Palazzo Vizzani. I couldn’t see the link with games, the theme of this year’s biennial, but the works in the show are smart and moving. Yassin lost many of his family photographs during the civil war in Lebanon. Along with this material loss, a part of his familial history and sense of identity disappeared. In order to overcome the trauma, Yassin began buying and collecting the family photographs of others, especially those from the Arab world where much displacement and revolutions took place over the last decades. The intimate nature of those captured moments helped him reconstruct a mental picture of his domestic upbringing.

As time passed, however, the presence of these unknown individuals grew intimidating and sometimes even haunting. So the artist spray painted the photographs of these people until only a faint trace of their silhouette remained. We cannot recognise the people and yet, they are still there, reminding us that they once existed.

Linda Fregni Nagler, Riverside Park (NY City, NY), 2007

Linda Fregni Nagler, Airplane (South Hampton, NY), 2007

Linda Fregni Nagler, Playgrounds, exhibition view at Palazzo Boncompagni, Bologna. Photo: Daniele Capra

Since 2006, Linda Fregni Nagler has been shooting playgrounds at night. Spaces that are associated with joy, children, movement and colours lose their function once the sun goes down. Their architecture becomes out-of-scale and their presence gloomy and intimidating.

More images from the biennale:

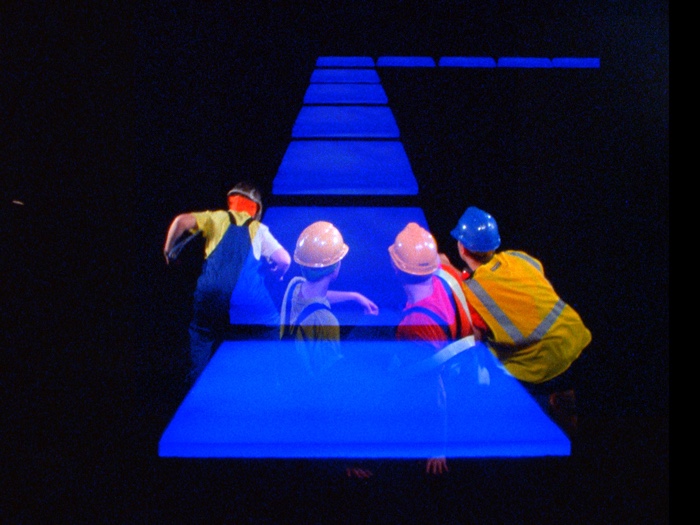

Ericka-Beckman, Reach Capacity, 2020

Ericka-Beckman, Reach Capacity, 2020

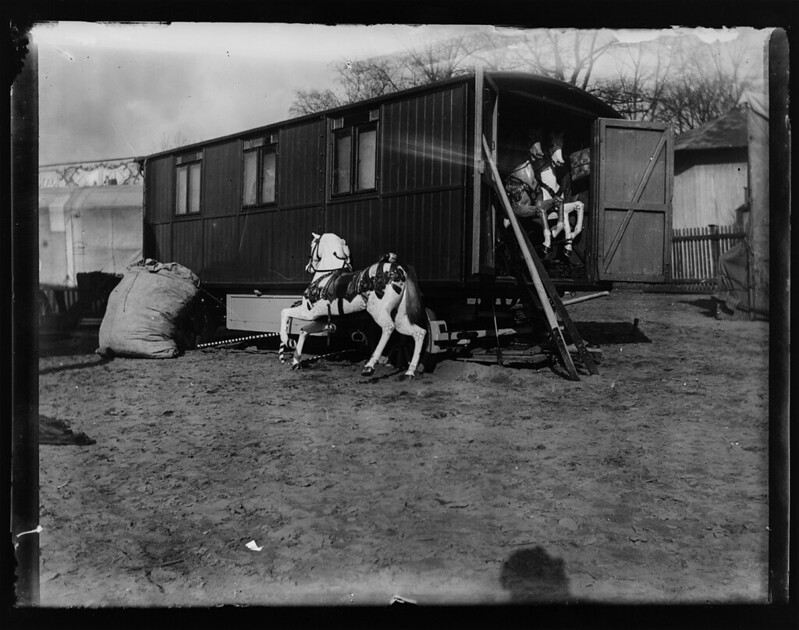

Heinrich Zille, Untitled, 1900. From the exhibition Berlin Funfair

Exhibition view of Heinrich Zille, Berlin Funfair at Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna / Casa Saraceni

Erik Kessels, Carlo and Luciana (In almost every picture 17), 2021

Erik Kessels, Carlo and Luciana (In almost every picture 17), 2021

GAME, the 2023 biennale of Foto/Industria remains open until 8 December in various venues across Bologna. Except Playgrounds at Palazzo Boncompagni.

Previous Foto/Industria stories: Foto/Industria. The political, technological and cultural dimensions of food, H+. We are all transhumanists now, Prospecting Ocean. The extractivist Wild West.