Using everything from artificial hot dogs and candy wrappers to Metrocards, NYC Parks employees and commissioned artists reimagine a Christmas classic.

Left: Marie Ucci, �The Shape of Dreams� (2023), acrylic, canvas, dryer lint, felted wool, dried fruit and vegetables, leaves, ceramic shards, wood, plastic, embroidery thread, wire, feathers; right: Suzie Sims-Fletcher, �All is Calm, All is Bright (Home for the Holidays)� (2023), cleaning puffs, scouring pads, foam, plastic mesh, rubber gloves

Left: Marie Ucci, �The Shape of Dreams� (2023), acrylic, canvas, dryer lint, felted wool, dried fruit and vegetables, leaves, ceramic shards, wood, plastic, embroidery thread, wire, feathers; right: Suzie Sims-Fletcher, �All is Calm, All is Bright (Home for the Holidays)� (2023), cleaning puffs, scouring pads, foam, plastic mesh, rubber gloves

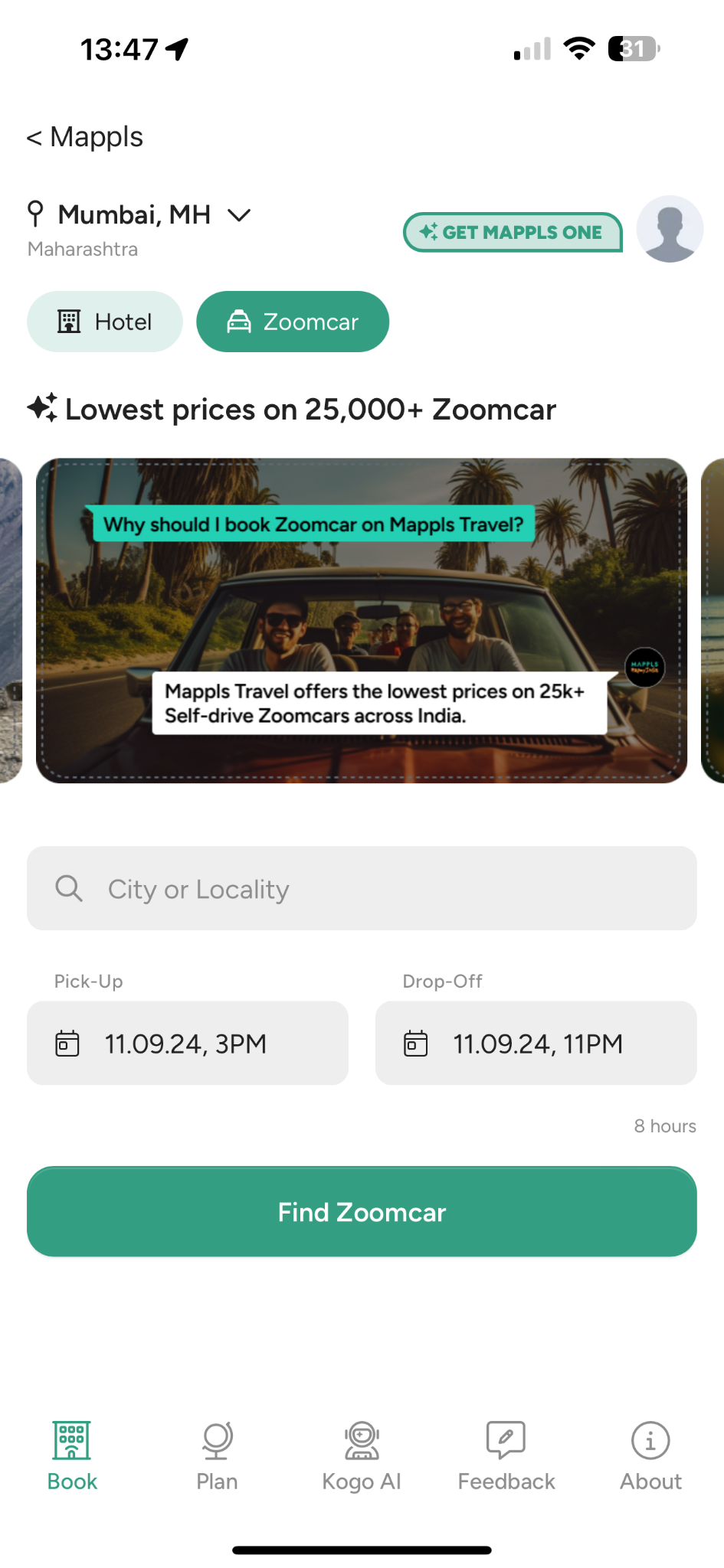

More than 30 original holiday wreaths handcrafted from unexpected materials, including discarded Metro cards, thumbtacks, artificial hot dogs, pharmaceutical vials, and candy wrappers, are currently on display in Central Park for the 41st iteration of New York City Parks�s Wreath Interpretations exhibition. Hosted in the third-floor gallery of the historic Arsenal Building, the annual free show brings together an eclectic assortment of alternative wreaths created by Parks employees, commissioned artists, and New York City residents for a whimsical display.

Wreaths have historically played a number of roles. In Roman and Greek antiquity, they were emblems of power and victory, frequently awarded to the winners of sporting competitions and appearing in depictions of various deities, such as Apollo in Antonio Canova�s marble sculpture �Apollo Crowning Himself� (1781�1782). In Christianity, evergreen wreaths symbolize eternal life and everlasting faith; during Advent season, laurel rings are decorated with four candles that are subsequently lit each week leading up to Christmas.

Left: Xiomara Morgan and Kathy Urbina, �FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY� (2023), styrofoam life preserver, found Metrocards, plastic waterbottles, candy wrappers, snack bags, labels, and bottle tops with a crocheted ribbon of plastic, rope, and caution tape; right: Audrey Zeidman, �Insomnia: Dream� (2023), plastic eyes, acrylic paint, and board

Left: Xiomara Morgan and Kathy Urbina, �FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY� (2023), styrofoam life preserver, found Metrocards, plastic waterbottles, candy wrappers, snack bags, labels, and bottle tops with a crocheted ribbon of plastic, rope, and caution tape; right: Audrey Zeidman, �Insomnia: Dream� (2023), plastic eyes, acrylic paint, and board

But the artists in Wreaths Interpretations, go beyond these classic meanings to transform a holiday staple into new works of art, from an aluminum and gold leaf display commemorating Caribbean cooking to a diorama wasp nest containing a hidden memorial honoring Ukraine. On one wall, an unsettling wreath crafted out of plastic eyeballs tackles sleep deprivation, while another piece made of yellow Post-It notes playfully comments on work-life imbalance.

In another corner, a pizza box with wiry rat tails emerging from the center � an unmistakable homage to the viral �Pizza Rat� � is situated between a spiral of playing cards and a ring of glistening frankfurters, humorously titled �THE WURST WREATH EVER MADE: YOU NEVER SAUSAGE A TERRIBLE WREATH� (2023). As Elizabeth Masella, Public Art Coordinator for the NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, told Hyperallergic, �the weirder, the better.�

Elizabeth Meggs, �THE WURST WREATH EVER MADE: YOU NEVER SAUSAGE A TERRIBLE WREATH� (2023) (all photos Maya Pontone/Hyperallergic unless noted otherwise)

Elizabeth Meggs, �THE WURST WREATH EVER MADE: YOU NEVER SAUSAGE A TERRIBLE WREATH� (2023) (all photos Maya Pontone/Hyperallergic unless noted otherwise)

�We�re always just impressed every year with the ideas that people come up with,� Masella continued. �I don�t think we�ve really seen the same materials twice.�

Edward Gormley, �Pizza Ratmas� (2023), cardboard, wire, and paper

Edward Gormley, �Pizza Ratmas� (2023), cardboard, wire, and paperMany of the artworks are constructed out of found objects and recycled materials, such as Xiomara Morgan and Kathy Urbina�s joint project �FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY� (2023), composed of found Metrocards, snack bags, and a styrofoam life preserver. Marie Ucci�s �The Shape of Dreams� (2023) is an assemblage of ceramic shards, dried fruits and vegetables, scraps of felted wool, and feathers, carefully pieced together like a bird�s nest, while Suzie Sims-Fletcher�s �All is Calm, All is Bright (Home for the Holidays)� (2023) comprises cleaning puffs, scouring pads, plastic mesh, and rubber gloves. Another wreath by Beatrice Wolert consists of a shredded tire with a bubblegum pink interior. Materials used in other displays include vinyl records, Popsicle sticks, garden fencing, and thumbtacks.

Several of the displays also focus on environmental issues plaguing the city�s parks. A work by Maria Magdalena Amurrio employs repurposed water bottles for a wreath of butterflies, an insect increasingly threatened by climate change and human development, while Jean-Patrick Guilbert�s �Coral Wreath� (2023) calls attention to the destruction of our oceans� coral reefs. Another wreath made of saltmarsh cordgrass, hay, lavender branches, and other natural materials native to Staten Island�s William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge tackles the issue of marsh degradation. The work was created over two days by a team of eight ecologists, wildlife biologists, and botanists from NYC Parks Environment and Planning.

Natalie Osadcija�s �A Glimpse into Paradise� (2023) made in collaboration with Varvara Osadcija and Deniss Osadcija appears as a wasps� nest on its exterior (left), but reveals to be an installation honoring Ukraine within its interior (right).

Natalie Osadcija�s �A Glimpse into Paradise� (2023) made in collaboration with Varvara Osadcija and Deniss Osadcija appears as a wasps� nest on its exterior (left), but reveals to be an installation honoring Ukraine within its interior (right).

�The wreath is meant to symbolize how New York City salt marshes are at risk of drowning from sea level rise under climate change,� Desiree Yanes, an NYC Parks wetlands restoration specialist, told Hyperallergic, pointing out the materials� symbolic placement around the circle.

�We�re very much a science driven team, but it was a really refreshing mindset shift just to undertake an artistic endeavor together,� Yanes added. �It was just a really nice breath of fresh air.�

Most of the wreaths on display are also available for purchase, ranging from $40 to $6,000. A portion of the sales proceeds goes to support the gallery and the Parks� public art programming. Visitors can view this year�s Wreaths Interpretations exhibition at the Arsenal Gallery located at 64th Street and Fifth Avenue until January 4, 2024.

NYC Parks Environment and Planning (Wetlands and Conservation Team), �Sea Level Rise and Marsh Loss� (2023), saltmarsh cordgrass, saltmarsh hay, saltgrass, seaside lavender, groundsel tree, ribbed mussels (image courtesy NYC Parks and Recreation)

NYC Parks Environment and Planning (Wetlands and Conservation Team), �Sea Level Rise and Marsh Loss� (2023), saltmarsh cordgrass, saltmarsh hay, saltgrass, seaside lavender, groundsel tree, ribbed mussels (image courtesy NYC Parks and Recreation) Carolyn Porpiglia, �Rx-mas� (2023), vinyl record, vials, popsicle sticks, and vial caps

Carolyn Porpiglia, �Rx-mas� (2023), vinyl record, vials, popsicle sticks, and vial caps

Leenda Bonilla, �Caldero Kintsugi� (2023), aluminum caldero, gold leaf, latex spray, rice, red beans

Leenda Bonilla, �Caldero Kintsugi� (2023), aluminum caldero, gold leaf, latex spray, rice, red beans

Beatrice Wolert, �Blown Out #001� (2023), found tire, house paint, acrylic, sumi ink

Beatrice Wolert, �Blown Out #001� (2023), found tire, house paint, acrylic, sumi ink