We Are Our Stories By Karen S. Musgrave We are our stories and this one is mine. How do I reach you and make you care about the stories behind quilts? By you I mean the public, researchers/academia,...

We Are Our Stories

By Karen S. Musgrave

We are our stories and this one is mine. How do I reach you and make you care about the stories behind quilts? By you I mean the public, researchers/academia, people I wanted to interview, workshop attendees, lecture attendees, readers of the articles I wrote and the manual that I edited for Quilters’ S.O.S. – Save Our Stories and the Alliance—so everyone. Even now after being away from interviewing for years, I want you to care. Though we have come a long way, women and quilts still face inequality. We can learn a lot about a quilt by looking at it, but that does not tell us the whole story. Listening to the quiltmaker does.

A little bit about me. I made my first quilt, for a baby, in 1974 after seeing an article in a magazine. Quilts were not a part of my life growing up. It wasn’t until I started doing genealogy that I learned that there were quiltmakers in my family. I, like many people interviewed, came to quiltmaking through sewing my own clothes. I didn’t know the “rules,” so the quilt was made with my drawings, rendered with fabric crayons using polyester/cotton blend fabric. From there, like many others, I created traditional quilts before moving on to create my own designs.

I came to Quilters’ S.O.S.- Save Our Stories (Q.S.O.S.) via Boxes Under the Bed™, the Alliance’s first project that dealt with quilt ephemera in 1996. I volunteered to go to the Boxes training as my guild’s representative. The guild’s board decided to hold an essay contest to determine who would attend. I spent weeks on my essay to end up being the only one to write one. I attended both training sessions that were offered at the International Quilt Festival in Houston. And while I felt it was important work, it did not excite me. I never imagined that attending the first Q.S.O.S. training would change my life in the ways that it did. After attending the training, I volunteered to put together a manual and worked for a year with the project’s volunteer task force members—Bernie Herman, Patricia Keller, Marcie Cohen Ferris and Pat Crews – and the manual was born.

Q.S.O.S. started by interviewing prize winners and people with quilts at the International Quilt Festival in Houston. Therese May’s interview from 2000 has stayed with me through all these years. It is not one that I conducted but was fortunate to sit in on. Therese’s honesty and openness left me in tears. It was the first time I cried during an interview, and it would not be my last. I think one of the most powerful questions ever asked is, “Have you used quilts to get through a difficult time?”

Marion Mackey and her quilt, 2000

Shortly after Therese’s interview, I was sent to the exhibition floor to interview Marion Mackey and to discover the story behind her quilt depicting baseball player Mark McGwire setting a home-run record. I was trying to remember everything I could about baseball. But it turned out the quilt had nothing to do with baseball. Her husband needed a liver transplant. He almost died twice while waiting. They were hoping and praying for a donor. Well, McGwire breaks the home-run record while they are watching it on TV, and then the phone rings and they get a liver. She started crying and I started crying. They travel with the quilt and talk to children’s groups about the importance of being an organ donor. This was another defining moment for me about why oral histories are so important.

Quilt Festival made conducting interviews easy, but I felt the interviews did not reflect the diversity of quiltmakers and their stories that were out in the world beyond Quilt Festival. So, my personal mission began. In the end, I conducted nearly 300 interviews, transcribed nearly 75 (not all mine) and read every interview posted online. For 10 years, I never went anywhere without my trusty $35 tape recorder and paperwork.

The interviews cover all sorts of territory, and often dispel common myths. There are traditional quiltmakers who think that art quiltmakers don’t do handwork. There is a notion that hand quilting is dying out—I don’t think that is the case. There’s the notion that you cannot be artful with a long arm machine. Reading the interviews and seeing the quilts helps set the record straight and eliminates these misunderstandings.

Here are a few things that I learned. Regardless of the skill level, creating something means that a part of us will still be around after we are gone. Quilts heal. Quilts can cause change. Quilts can create awareness. Quilts can be a source of much needed income. Some people are more open to sharing than others. Some people regret how much they shared.

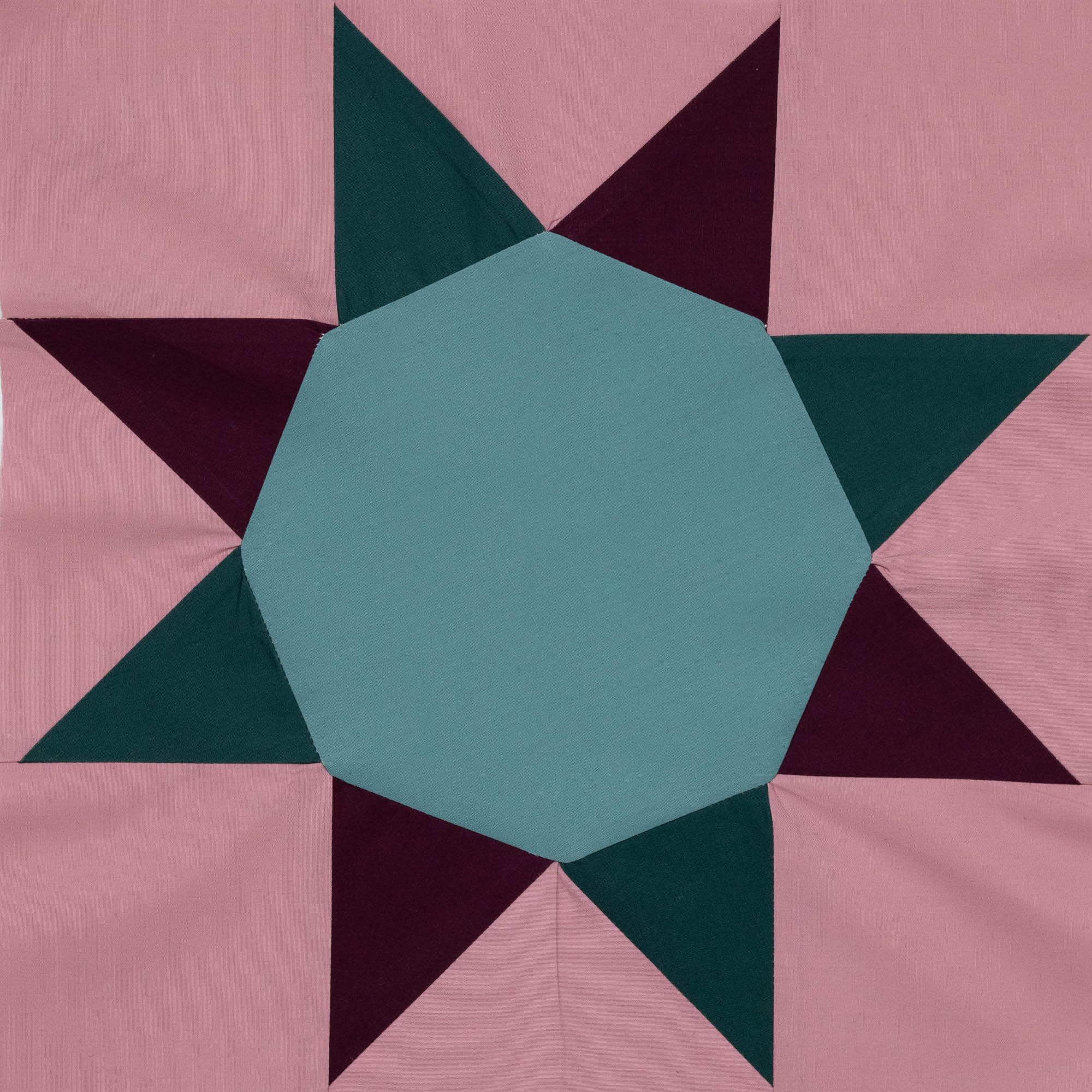

Angeles Segura and her quilt

Interviewing Latina quiltmakers and their children, especially those in northern California, gave these makers a way to share their stories about the impact in their lives from the income they made from selling their quilts. I will be eternally grateful to the Salser Foundation for supporting me and Molly Johnson Martinez who was the organizing force behind the group. Los hilos de la vida (The Threads of Life),a mostly Latina cooperative quilt group, was quietly making pictorial quilts for years before I arrived. Their quilts depict scenes of family life, border crossings, life in Mexico, dreams, and reverence for the natural and spiritual worlds. Vibrant with color, the quilts make an immediate impression on the viewer as they unselfconsciously capture the pure essence of the women’s stories. Even more impressive, the women had little or no previous experience creating art or quilts. Angeles Segura’s quilt shows her asleep on her GED diploma surrounded by the things she loves—her books and her guitar. The mother of four, she worked in the vineyards while studying for her diploma.

Some of the most compelling quilts are those that depict scenes about crossing the border into the United States. Carmela Valdivia has created many border crossing quilts, which always have the figure of death somewhere in them.

After returning from California, my mission became to help the group gain more recognition. I immediately made the first of many attempts to get the attention of the National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) in Chicago. Success was achieved when two of the group’s quilts hung in the museum’s exhibition Declaration of Immigration. I also curated an exhibition at the Pacific International Quilt Festival XVII, in Santa Clara, California. Unfortunately, funding ended for the program that supported the group which means the interviews I was able to conduct now provide a glimpse of something that no longer exists. My involvement with Hilos led me to start a quilting group at the NMMA. Again, the participants had never made quilts before, and many had never used a sewing machine. However, unlike the women of Hilos, many of the women had immigrated to the United States when they were young, and all had legally immigrated. The quilts are no less powerful. Maria Tortolero’s detailed quilt is split in two—one side depicts her life in Mexico and the other side her life in Chicago. Maria Herrera’s quilt honors her father and the stories of his immigration adventures and traveling around the United States to find work. “My quilt is …based on my dad/s journey from Mexico to the United States…I started recording my dad’s stories because I wanted my son to grow up hearing my dad’s stories…the stories I grew up hearing…I know that when my dad seed this quilt and a bit of his life in this quilt…he is going to start crying…My dad’s journey is being told through this quilt.” By the way, he did cry. The group at NMMA also created quilts that dealt with the torture, rape and murder of young women and children in Juarez, Mexico. The difficult subject matter produced incredibly thought-provoking quilts. Christina Carlos’ message, “al fub…en paz/ Finally at Peace,” is typical in that it expresses young girls no longer suffering and in a better place. I think Luz Maria Carillo expresses something universal when she said, “Each one of us leaves a piece of our hearts in each quilt that we make.”

Spike Gillespie, 2009

A handful of people that I interviewed (who did not know me) asked about me personally. One of them was the writer Spike Gillespie, who had begun writing about quilts at the time of her interview. After our conversation, she invited me to write essays for her book Quilts Around the World about my involvement with Q.S.O.S., Latina quiltmakers and my work with connecting American quilts with quilts or patchwork in the countries of Georgia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. My connections to the Alliance through one of the founders and then president, Shelly Zegart, provided me with the connection to take an exhibition of quilts from Gee’s Bend, Alabama to Georgia, Armenia, and Kazakhstan. These quilt exhibitions provided a link in a global movement to revive interest in traditional culture and crafts. They illustrate the shared common threads in our arts and cultures—highlighting what makes us unique and embracing our commonalities. Interviews with some of the members of the Georgian Quilt Group can be found in the Q.S.O.S. project. My writing for Spike’s book led to an invitation to author my book – Quilts in the Attic – Uncovering the Hidden Stories of the Quilts We Love.

I was also interested in gathering interviews of how quiltmaking can make a difference for incarcerated people. I found a quilting program in a Minnesota detention center for men. After months of answering questions and even signing papers stating I did not expect to be rescued if taken hostage, the warden decided without any explanation to pass on the project. I was devastated. Fortunately, in 2009, I was able to interview women who had participated in a quilt project featured in an exhibit called “Sacred Threads” in Columbus, Ohio. The Ohio Reformatory for Women (ORW) is just outside of Columbus in Marion, Ohio. Driving down the long road to the prison passing fields filled with wildflowers, it was such a shock to see buildings surrounded by a tall wire fence with razor wire on top. The warden required the women to state the reason that they were incarcerated at the beginning of each interview. It was explained to me that this requirement was to get the women to realize they were accountable and become more comfortable talking to strangers about why they were there. I made it clear before the tape recorder was turned on that I did not care why they were there. I cared about their experience making a quilt. None of them had made one before. The assistant to the warden was also present in the room during the interviews. She worked quietly a few tables away and I made sure to sit so that the women would have their back to her. I continued my relationship with these women after their interviews and with a few even until today.

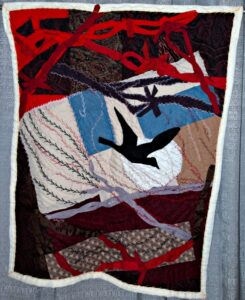

Rhonda Edwards was the most intense interview and one that I wished we had videotaped. Her quilt shows her split in two- her life before and her life after. Rhonda is a talented artist, so her quilt is full of her drawings. It also expresses her journey from a violent person to one who has found God, from a person who was deeply grieving her father’s death to someone who feels joy. Rhonda sent her quilt to her mom. The women were not allowed to have the quilts in their possession.

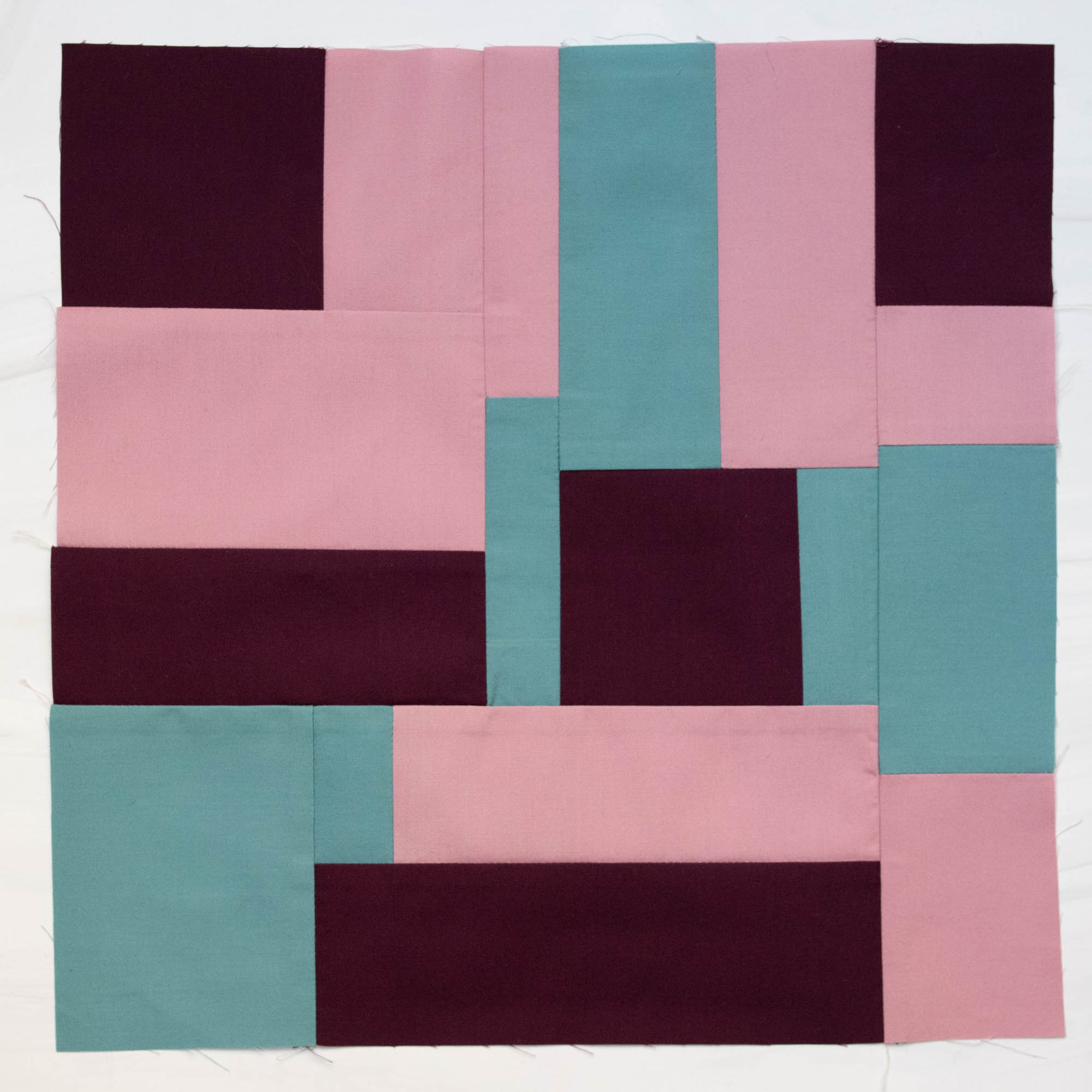

“Hope” by Rosa Angulo

Rosa Angulo’s quilt is called “Hope.” Her artist statement says so much about her quilt, “I want to give my first quilt the name of hope–Because I’m trying to express it somehow. My life in this place is the patches and the stitches are the different stages I’ve been going through. The ribbons are the razor wire that surrounds this prison. And the eagle is me, who with the help I’ve been getting from recovery and religious services, and some of the staff members, I feel I will have the tools to fly when my time gets here. Like it says in Isaiah 40:31 ‘They that hope in the Lord will renew their strength, they will soar as with eagles’ wings; they will run and not grow weary, walk and not grow faint.’“ And she added as a personal note: “I am 48 years old and the mother of three beautiful daughters and the grandmother of an eight-year-old girl. I work as a porter in my cottage, and love to do community service through the Stitching Post (a place to gain skills and employment sewing items for nonprofit organizations, many dealing with children). I’ve never made a quilt before, but I really enjoyed working on this one.” Rosa was deported to Mexico upon her release. She had sent her quilt to her eldest daughter. I never heard from Rosa after her release. I do hope that the skills she learned while at ORW continue to help her and that her desire to make more quilts continues.

Once the interviews were posted and several articles about them were written, I received threats from some of the women’s victims’ families. Nothing came of them, and I certainly understand their anger and pain, yet I still feel the interviews should be included in the Q.S.O.S. collection..

Lois Beardslee, 2007

I was not as successful in getting Native American quiltmakers into the project. It was only by chance that I interviewed Lois Beardslee. We met while I was working in northern Michigan. Her interview was conducted in her bedroom while sitting on her quilt. “I started piecing our old clothing and old blue jeans, everything…old handkerchiefs, old pillowcases, everything…this is {a piece from] my wedding dress…It was my son who one day took the sleeves off, and my husband said, “’Oh, no.’ I told him, ‘See, it is not about the dress. It is about the being married to you and growing old with you.’…It is a great quilt because it is our lives all wrapped up into one package.”

Interviews with people included in exhibitions truly capture a moment in time and continue the historical use of quilts to communicate social or political messages. The exhibition-based projects include interviewing people who made quilts to celebrate the election of Barack Obama as president and the Ancestor Project that took place at the American Indian Center in Chicago where women from the senior lunch program stayed to appliqué designs of ancestral portraits, animal spirits and plants. Other exhibition-based projects include the Alzheimer’s Forgetting Piece by Piece and Priority Alzheimer’s Quilt projects led by Ami Simms, that helped raise awareness of Alzheimer’s and funds for research, and Healing Quilts in Medicine project to name a few.

There are so many times that I wish I could have left the recorder going because far too often that is when amazing things were shared. They weren’t always about the quilt or quilts in general, but they provided intimate details or funny stories that I wish everyone knew.

Interviewees were given the transcription of their interview to review before it was published online and archived. One interviewer called me quite upset stating that she did not talk the way the transcription portrayed her. She “most certainly did not have a potty mouth.” I tried explaining that transcribers do not add or subtract from the interviews. Still not satisfied, I played the tape for her. In another interview, the person shared details about other quiltmakers that they regretted and so the comments were removed. After one Houston interview, I encouraged editing because I thought it would hurt the interviewee’s reputation, but she stood by her words.

I was pleasantly surprised by the deep friendships that happened because of interviewing people. I am so thankful that I was able to interview Yvonne Porcella, Merry Silber, Gwen Marston, Elizabeth Cherry Owen, Maxine Groves and Lisa Quintana, who are no longer with us.

I think my proudest moment was after we lost our original archives at the University of Delaware. As the chair of the task force, I had to find a new archival home for the collection. Board members volunteered their universities as potential partners, but I set my goal higher. With the help of David Taylor, I wrote a successful proposal to the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress.

Repeatedly, historians often run into the same obstacle when working to identify information about a historic quilt: a dearth of clues as to the origin, maker, and story. That means a lot of mystery remains. And while Q.S.O.S. might not help today’s historians solve certain mysteries of the past, the interviews will leave behind a legacy for historians of the future.

While interviewers probably did not set out to touch another’s feelings and longings, words and images emerge in interviews that are just as universal as they are personal. Q.S.O.S. has provided a place where quiltmakers’ stories are accessible, where others can draw on them for strength and make a connection. This is the gift that volunteer interviewers will continue to give for years to come.

I will close with my favorite quote by Betty Reese and one I use at the end of my lecture, “If you think you are too small to be effective, you’ve never been in bed with a mosquito.”

About Karen

Karen S. Musgrave is an interdisciplinary, multihyphenate artist whose recent body of work deals with loss, memory, and identity. She feels passionately about connecting cultures with quilts. Her projects include curating a traveling exhibition of the African American quilts from Gee’s Bend, Alabama, alongside quilts in Georgia, Armenia, and Kazakhstan. In Kyrgyzstan, she organized, curated, and wrote the catalogue for an exhibition of American art quilts and Kyrgyz patchwork. She has served on numerous nonprofit boards. She was a consultant on the 9-part documentary Why Quits Matter. As a writer, she contributed to Spike Gillespie’s book quilts Around the World, wrote the book Quilts in the Attic: Uncovering the Hidden Stories of the Quilts We Love and has written numerous articles for magazines. She has exhibited internationally, and her work is in many different private collections. She lives in the far west suburbs of Chicago.