In the annals of human thought, few concepts have captivated the imagination as profoundly as the ancient astrological cosmology. This cosmological framework, deeply rooted in the observation of celestial bodies, posits a universe where Earth is encircled by concentric...

Dear NightFall Astrology readers,

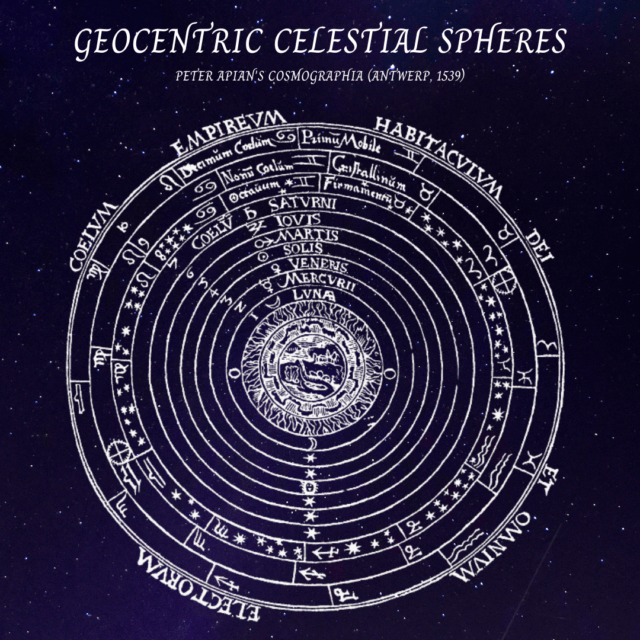

In the annals of human thought, few concepts have captivated the imagination as profoundly as the ancient astrological cosmology. This cosmological framework, deeply rooted in the observation of celestial bodies, posits a universe where Earth is encircled by concentric celestial spheres, each carrying a planet or stars. This geocentric model, a cornerstone of ancient and medieval science, was not merely a scientific theory but also a philosophical and spiritual scaffold that shaped the worldview of entire civilisations.

The significance of the celestial spheres extends far beyond their astronomical function. In historical context, they represented the harmony and order of the cosmos, reflecting a deeply ingrained belief in a universe that was both intelligible and meticulously structured. This structure was seen as a macrocosm, mirroring the microcosm of human society and individual existence. The movements and positions of celestial bodies within these spheres were thought to hold profound implications for terrestrial events and individual destinies, a concept that underpinned much of ancient astrology.

The purpose of this article is to delve into the philosophical underpinnings of ancient astrological cosmology, tracing its development, structure, and impact on human thought. It aims to illuminate how these celestial concepts shaped not only scientific understanding but also philosophical and theological discourse throughout history. The scope of this exploration extends from the early astrological traditions of Mesopotamia and Egypt, through the philosophical refinements of the Greeks, to the enduring legacy in medieval and Renaissance thought.

In pursuing this exploration, this article draws upon a range of historical and philosophical sources. Central to this study are seminal works such as Ptolemy’s “Almagest”, which offers an extensive account of the geocentric model, and Aristotle’s “Metaphysics”, which provides crucial insights into the philosophical interpretation of celestial phenomena. These works, along with a host of other historical texts and modern scholarly analyses, form the foundation of a comprehensive examination of one of humanity’s most enduring attempts to understand the cosmos and our place within it.

I. Historical Context and Development:

The evolution of ancient astrological cosmology is a tapestry woven from various cultural and intellectual threads, beginning in the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. In Mesopotamia, astrology emerged from a pragmatic need to predict seasonal changes for agricultural purposes. This utilitarian approach soon evolved into a more complex system, as evidenced in the “Enuma Anu Enlil”, a series of cuneiform tablets detailing celestial omens (Rochberg, 2004). Egyptian astrology, meanwhile, was deeply intertwined with their religious and ceremonial life, as seen in the alignment of their pyramids and temples with celestial bodies, a practice aimed at harmonising earthly and celestial realms (Krupp, 1997).

The Greek synthesis of the rich astrological traditions of Mesopotamia and Egypt marked a watershed moment in the history of cosmology. This synthesis, characterized by a profound blend of empirical observation and philosophical speculation, was significantly advanced by the works of Greek philosophers, notably Plato. In his seminal dialogue “Timaeus”, Plato introduced a cosmological vision that transcended mere physical description, venturing into the realm of the deeply philosophical.

Plato’s cosmology was not just an attempt to explain the physical structure of the universe but was also a profound exploration of its underlying principles. He envisaged a cosmos that was not the product of random formation but one that was meticulously crafted by a divine artisan, a Demiurge. This divine craftsman, in Plato’s vision, imposed a mathematical order upon the cosmos, transforming it from a state of chaos to one of harmony and rationality. This concept of a universe governed by mathematical laws was revolutionary, suggesting an inherent order and intelligibility to the cosmos (Cornford, 1997).

This idea of a harmonious and rational universe laid the groundwork for later astronomical theories. Plato’s emphasis on mathematical order in the cosmos would influence subsequent generations of thinkers, who sought to uncover the mathematical relationships governing celestial phenomena. His portrayal of the universe as a well-ordered whole, governed by rational principles, was a precursor to the later scientific understanding of the cosmos. It was this blend of philosophical inquiry and mathematical precision that set the stage for the development of a more systematic and empirical approach to astronomy.

Moreover, Plato’s cosmology, with its emphasis on ideal forms and the role of a divine creator, also had profound implications for the philosophical and theological thought of the time. It bridged the gap between the physical and the metaphysical, suggesting a universe that was not only a physical entity but also a manifestation of higher, more abstract principles. This dual perspective would be a defining feature of much of Western thought in the subsequent millennia.

Aristotle’s contribution to the field of astrological cosmology, particularly through his work “On the Heavens”, represents a significant advancement and expansion of the ideas introduced by his predecessors, including Plato. In this seminal treatise, Aristotle proposed a geocentric model of the universe, which was characterised by a series of concentric spheres, each carrying a celestial body such as the Moon, the Sun, the known planets, and the stars. This model was revolutionary in its attempt to provide a comprehensive explanation of the observed celestial motions within a coherent framework.

However, Aristotle’s model was not merely a physical description of the universe; it was deeply imbued with his philosophical insights about the nature of reality. In Aristotle’s view, the universe was a dichotomy of two realms: the sublunary sphere, characterized by change and imperfection, and the celestial realm, which was eternal, unchanging, and perfect. The motion of the celestial spheres was seen as uniform and circular, reflecting the perfection of the heavens, in stark contrast to the linear and irregular movements observed in the terrestrial realm (Lindberg, 2007).

This distinction between the celestial and the terrestrial was a profound philosophical statement about the nature of change and permanence. Aristotle posited that while the earthly realm was subject to growth, decay, and various forms of alteration, the celestial realm was immutable, governed by a different set of principles that underscored its perfection. This concept not only provided a framework for understanding the physical structure of the universe but also offered a metaphysical perspective on the nature of existence itself.

Moreover, Aristotle’s model had significant implications for the development of later astronomical and philosophical thought. His emphasis on the uniform circular motion of celestial bodies influenced the way astronomers for centuries would conceptualise and attempt to calculate celestial movements. The Aristotelian universe, with its clear demarcation between the celestial and the terrestrial, also had a lasting impact on the medieval worldview, intertwining with theological doctrines and influencing the way the cosmos was perceived in the context of Christian thought.

The Hellenistic period, a vibrant era of cultural and intellectual fusion following the conquests of Alexander the Great, witnessed a remarkable synthesis of philosophical concepts with observational astronomy. This synthesis was most notably fostered in the renowned Library of Alexandria, an institution that stood as a beacon of knowledge and scholarly pursuit. The library, more than just a repository of texts, was a dynamic crucible of intellectual activity, attracting scholars from across the known world. These scholars, drawn from diverse cultural and intellectual backgrounds, engaged in the study and expansion of astronomical knowledge, blending empirical observation with philosophical inquiry (Philo of Byzantium, 1st century BC).

This era was marked by significant advancements in the field of astronomy, largely due to the contributions of key figures such as Hipparchus and Ptolemy. Hipparchus, often regarded as the father of trigonometry, pioneered the use of quantitative methods in astronomy. His systematic and mathematical approach to celestial phenomena represented a significant departure from the primarily qualitative and descriptive methods of earlier times. Hipparchus’s work included the development of a star catalogue, the discovery of the precession of the equinoxes, and the refinement of methods for predicting solar and lunar eclipses, laying the groundwork for future astronomical research (Jones, 2017).

Ptolemy, another towering figure of this period, made monumental contributions with his work “Almagest”, a treatise that not only summarised and expanded upon the astronomical knowledge of his predecessors but also presented a comprehensive system of the heavens. “Almagest” was a culmination of the Hellenistic synthesis of astronomy, combining mathematical rigour with a geocentric cosmological model. Ptolemy’s model, with its complex system of epicycles and deferents, offered explanations for the movements of celestial bodies and profoundly influenced astronomical thought for the next fourteen centuries. His work represented the zenith of ancient astronomy, combining observational precision with a sophisticated theoretical framework (Toomer, 1998).

In summary, the historical development of astrological cosmology is a journey from practical observation to philosophical abstraction, and finally to a sophisticated synthesis of the two. This journey, documented in works like “Babylonian Star-lore” by Gavin White and “The Fated Sky” by Benson Bobrick, reflects humanity’s enduring quest to understand the cosmos and our place within it. The legacy of this quest is a rich intellectual tradition that laid the foundations for modern astronomy and continues to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts alike.

II. The Structure of the Celestial Spheres:

The geocentric model of the universe, which prevailed in ancient and medieval astronomy, presents a fascinating and complex view of the cosmos. At the heart of this model is the Earth, stationary and central, around which all celestial bodies are believed to revolve. This concept, deeply rooted in the works of Aristotle and later refined by Ptolemy, posits a series of concentric spheres, each carrying a celestial body (Toomer, 1998).

The seven classical planets, known to the ancients, play a crucial role in this model. In ascending order from the Earth, they are the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. This order reflects the apparent speed and distance of these bodies from the Earth, with the Moon being the closest and Saturn the farthest in the ancient conception. Each planet was thought to move in its sphere, with the Sun holding a special place, often considered the ruler of the day and a marker of time (Hoskin, 1999).

Beyond the spheres of these planets lies the realm of the fixed stars and the zodiac. Unlike the planets, which exhibit individual motion, the fixed stars were believed to reside on a single celestial sphere. This sphere rotates diurnally around the Earth, carrying with it the constellations of the zodiac. The zodiac, a band divided into twelve equal parts, each named after the constellation that once occupied it, plays a significant role in astrology. The movement of planets against the backdrop of these zodiacal constellations forms the basis for astrological interpretations (Ptolemy, 2nd century).

The theoretical implications of celestial motion in the geocentric model are profound. The apparent retrograde motion of planets, where they appear to move backward in the sky, presented a significant challenge to early astronomers. To account for this, Ptolemy introduced the concepts of epicycles and deferents – smaller circles within the larger circular orbits of the planets. This complex system allowed for the prediction and explanation of the irregular movements observed from Earth (Toomer, 1998).

Furthermore, the geocentric model encapsulates a worldview where the Earth, and by extension humanity, is at the centre of the universe. This anthropocentric perspective had significant philosophical and theological implications, reinforcing the idea of a cosmos designed with a purposeful order, with humanity as a focal point of creation. The model also reflects the limitations of observational astronomy in ancient times, where the lack of telescopic technology restricted the understanding of celestial phenomena to what could be observed with the naked eye (Hoskin, 1999).

In conclusion, the structure of the celestial spheres in the geocentric model represents a remarkable synthesis of observation, philosophy, and theology. It stands as a testament to the ingenuity and intellectual rigour of ancient and medieval astronomers, who sought to understand the cosmos despite the limited observational tools at their disposal. The legacy of this model, with its intricate mechanisms and anthropocentric view, continues to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts of astronomy and the history of science.

III. Philosophical Interpretations:

The celestial spheres, more than just components of a cosmological model, have been interpreted through various philosophical lenses throughout history. These interpretations provide a deeper understanding of how ancient and medieval societies viewed the universe and their place within it.

A. The Spheres as a Reflection of the Divine Order:

1°) Neoplatonism and the Emanation of the Spheres:

Neoplatonism, a philosophical system that emerged in the 3rd century, profoundly reshaped the understanding of the celestial spheres. This school of thought, initiated by the philosopher Plotinus and his followers, viewed the cosmos through a lens that was both metaphysical and spiritual. Central to Neoplatonism, as articulated in Plotinus’ seminal work, the “Enneads”, is the concept of emanation, a process in which all existence is understood to flow from a singular, ultimate source known as the One. This source, ineffable and transcendent, represents the pinnacle of unity and the origin of all being.

In Neoplatonic cosmology, the celestial spheres are far more than mere physical structures or astronomical mechanisms; they are envisioned as crucial stages in the emanation of the universe from the One. Each sphere is seen as a distinct level of existence, progressively distancing from the pure, undifferentiated form of the divine. The outermost sphere, associated with the fixed stars, is considered closest to the One in terms of perfection and uniform motion. In contrast, the inner spheres, corresponding to the planets, are marked by increasing complexity and diversity, indicative of their further remove from the divine source.

This framework provided a model for understanding not only the physical structure of the universe but also a profound spiritual and metaphysical vision. The journey of the soul is a central theme in Neoplatonic thought. According to this philosophy, the soul originates from the One and descends through the celestial spheres, acquiring various characteristics and influences from each. This descent leads to a forgetfulness of its divine origin, a state that is the root of human suffering and ignorance.

The ultimate aim in Neoplatonism is the soul’s ascent back through the celestial spheres, a journey of spiritual purification and enlightenment. As the soul ascends, it sheds the influences acquired during its descent, moving closer to a state of unity and purity. This ascent is envisioned as a reintegration with the One, a return to a state of divine knowledge and bliss.

Thus, Neoplatonism, particularly under Plotinus and his school, transformed the concept of the celestial spheres from a mere astronomical construct into a symbol of spiritual ascent and enlightenment. The spheres become stages in both cosmic and personal evolution, guiding the soul back to its ultimate origin and purpose. This interpretation intertwines cosmology with a deeply spiritual vision, offering a pathway to transcendence through the structure of the universe itself.

The influence of Plotinus and Neoplatonism was profound, impacting philosophical and theological thought, as well as Western mysticism and esoteric traditions. The Neoplatonic view of the celestial spheres as stages of emanation and the soul’s journey provided a rich symbolic framework, resonating through subsequent ages and influencing a wide array of thinkers, artists, and mystics.

2°) The Role of the Prime Mover in Aristotelian Thought:

Aristotle’s concept of the Prime Mover, a central tenet in his philosophical and cosmological framework as detailed in his work “Metaphysics”, represents a pivotal development in ancient thought about the cosmos. This concept is Aristotle’s solution to a fundamental paradox: the existence of motion and change in a universe that he believed should ultimately be grounded in a perfect and unchanging first cause.

The Prime Mover, according to Aristotle, is an unmoved mover – a being that incites all motion and change in the universe without itself undergoing any change or movement. This entity is not physical but metaphysical, existing outside the realm of the observable universe and its phenomena. The Prime Mover is perfect and unchanging, embodying the pinnacle of existence and thought. It is the ultimate cause of all motion in the universe, particularly the motion of the celestial spheres, which, in Aristotle’s view, move in perfect and eternal circles (Aristotle, 4th century BC).

Aristotle’s introduction of the Prime Mover was an attempt to reconcile the observed motion in the heavens with his philosophical principles. He observed that everything in motion must be set in motion by something else. However, this chain of motion cannot regress infinitely; there must be a first cause, a source of motion that itself is unmoved. The Prime Mover, therefore, is this source. It moves the celestial spheres not through physical interaction but through its nature as the ultimate object of desire and purpose. The spheres, striving for perfection, move in emulation of the perfection embodied by the Prime Mover.

This concept also reflects Aristotle’s belief in a cosmos that is rational and ordered. The Prime Mover, as the ultimate cause and source of order, imparts a structured, purposeful nature to the universe. This idea was revolutionary, suggesting that the universe operates according to a set of principles that can be understood and explored through reason and observation.

Furthermore, the role of the Prime Mover in Aristotle’s thought has profound theological and metaphysical implications. It presents a view of the universe that is not only governed by physical laws but also underpinned by a metaphysical reality. The Prime Mover becomes a bridge between the physical world of change and the metaphysical world of perfection and permanence.

In summary, Aristotle’s concept of the Prime Mover is a cornerstone of his philosophical and cosmological theories. It serves as a physical explanation for the movement of the celestial spheres and as a metaphysical principle that underscores the rational, ordered nature of the cosmos. This concept has had a lasting impact on subsequent philosophical and theological thought, influencing how generations have conceptualised the relationship between the physical universe and its underlying principles.

B. Astrology and the Human Condition:

1°) Fate, Free Will, and the Stars:

The intricate relationship between the celestial bodies and human destiny has long been a focal point in the realm of astrological thought, weaving a complex tapestry that intertwines fate, free will, and the stars. The positions and movements of the stars and planets, as observed and interpreted by astrologers, have traditionally been seen as potent indicators of fate, exerting a significant influence on the unfolding of human affairs. This perspective posits that celestial phenomena, through their configurations and cycles, hold sway over the course of human life, from the grand sweep of historical events to the minutiae of individual existence (Tester, 1987).

However, this deterministic view of astrology, where human lives and destinies are seemingly preordained by the celestial order, is counterbalanced by the concept of free will. The debate over fate versus free will is a longstanding one, with many astrologers and philosophers advocating a more nuanced understanding. They propose that while the stars and planets may indeed suggest certain tendencies, predispositions, or potentialities, they do not dictate the course of human life in an unalterable manner. Instead, these celestial indicators serve more as a guide or a map, outlining possibilities and challenges.

Human agency and choice, therefore, are accorded a significant role in this interplay. The idea is that individuals, through their actions and decisions, have the power to shape and even alter their destinies. This perspective aligns with the philosophical stance that while certain aspects of life may be influenced by external factors, the ultimate direction and quality of one’s life are largely determined by personal choices and actions. In this view, the stars may set the stage, but it is the individual who plays the leading role in their life drama.

This dialectic between fate and free will in astrology is reflective of a broader philosophical inquiry into the nature of human existence and agency. It raises profound questions about the extent to which our lives are governed by forces beyond our control versus the degree to which we are the architects of our own fates. This debate touches on fundamental philosophical concepts such as determinism, existentialism, and the nature of human consciousness and decision-making.

The astrological perspective, therefore, offers a unique lens through which to explore these age-old questions. It presents a worldview in which the cosmos and human life are deeply interconnected, with celestial phenomena providing a symbolic language for understanding and navigating the human experience. Yet, it also acknowledges the crucial role of individual agency, suggesting that while the stars may guide us, they do not bind us.

In essence, the relationship between fate, free will, and the stars in astrological thought is a dynamic and complex one. It encapsulates the tension between the cosmic blueprint and human autonomy, inviting a contemplative exploration of how we navigate our journey through life within the broader tapestry of the universe.

{ For further exploration of this subject, check my article entitled

“Astro Philosophy: Free Will, Determinism, & the Causal vs. Reflective Nature of Astrological Interpretation” HERE! }

2°) Astrology as a Tool for Understanding Human Affairs:

Astrology, throughout ancient and medieval history, has been much more than a system for predicting future events. It has served as a profound tool for understanding the intricacies of the human condition, providing insights that extend far beyond the mere forecasting of terrestrial happenings. In these eras, astrology was deeply intertwined with the philosophical and spiritual understanding of the world. It was perceived as a key to unlocking the mysteries of the divine plan and the natural order, offering a unique perspective on the interplay between celestial dynamics and human affairs.

The role of astrology in these times was multifaceted. On one hand, it was seen as a means to gain insight into individual personalities and behaviours. The belief was that the positions and movements of celestial bodies at the time of one’s birth could significantly influence one’s character and life path. This aspect of astrology provided individuals with a framework for self-understanding and personal growth, offering explanations for traits and tendencies that seemed otherwise inexplicable (Tester, 1987).

On the other hand, astrology was also a tool for understanding broader societal trends and dynamics. Astrologers would interpret celestial signs to provide guidance on a wide range of communal and political matters. This practice was based on the premise that the macrocosm (the universe) and the microcosm (human society) were reflections of each other. Thus, by understanding the patterns and movements in the heavens, one could gain insight into the affairs of societies and nations. This approach was particularly prevalent in the decision-making processes of rulers and statesmen, who often consulted astrologers for guidance on governance and political strategy (Tester, 1987).

Furthermore, astrology in these periods was a means of connecting with the divine. The celestial bodies were often seen as messengers or manifestations of the gods or a higher power. By interpreting the movements and positions of these celestial entities, astrologers believed they could decipher the will and intentions of the divine. This practice imbued astrology with a sacred quality, making it an integral part of religious and spiritual life.

The practice of astrology, therefore, was a reflection of a worldview in which the cosmos was seen as intimately connected with human life. The movements of the stars and planets were not just distant and impersonal phenomena; they were deeply relevant to every aspect of human existence, from the individual to the collective, from the mundane to the spiritual. Astrologers, with their interpretations of the celestial signs, served as mediators between the heavens and the earth, providing guidance and insight drawn from their understanding of the cosmic order.

In summary, astrology in ancient and medieval times functioned as a comprehensive tool for understanding human affairs. It was a discipline that blended predictive capabilities with deep philosophical and spiritual insights, offering guidance in both personal and political realms. This historical perspective on astrology highlights its significance as a cultural and intellectual practice that sought to harmonize human understanding with the rhythms and patterns of the wider universe.

C. The Spheres in Medieval Philosophy and Theology:

1°) Integration with Christian Doctrine:

In the rich tapestry of medieval Christian thought, the celestial spheres were not only integral to the cosmological understanding of the universe but also deeply embedded in the theological framework of the era. This integration of celestial concepts into Christian doctrine represented a harmonious fusion of ancient astronomical knowledge with the spiritual principles of Christianity, imbuing the spheres with profound theological significance.

Historically, this integration can be seen in the works of influential Christian thinkers like Thomas Aquinas. In his seminal work, “Summa Theologica,” Aquinas incorporated Aristotelian and Ptolemaic cosmology into Christian doctrine, using the framework of the celestial spheres to explain the nature of the physical universe in alignment with Christian teachings. He posited that these spheres, as part of God’s creation, were a manifestation of divine order and wisdom (Aquinas, 13th century).

The celestial spheres, within this Christianised framework, were perceived as a vital part of God’s creation. This perspective was largely influenced by the Ptolemaic model, which depicted a series of concentric spheres with Earth at the centre. In the Christian interpretation, these spheres were more than mere physical entities; they were seen as a manifestation of divine wisdom and power, a cosmic order set by God himself. This view is exemplified in Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy,” particularly in “Paradiso,” where the poet describes a journey through the celestial spheres, each reflecting a higher level of spiritual perfection and closer proximity to God (Dante, 14th century).

Angels played a crucial role in this Christian cosmology, often associated with the movements of the celestial bodies. Each sphere was thought to be governed by a specific order of angels, responsible for the movement and harmony of the celestial bodies within that sphere. This concept is vividly illustrated in the writings of medieval scholars like Hildegard of Bingen, who in her visionary works, described a universe where angels interacted with the celestial spheres, acting as divine agents of God’s will (Hildegard of Bingen, 12th century).

Furthermore, the celestial hierarchy was seen as a reflection of the ecclesiastical hierarchy on Earth. Just as angels were arranged in a hierarchical order in heaven, so too was the Church on Earth. This parallel served to reinforce the idea of a divinely ordained structure encompassing both the heavenly and earthly realms. The Church, with its structured hierarchy of clergy, mirrored the celestial order, symbolising a cosmic and spiritual order believed to be established by God.

This integration of the celestial spheres into Christian doctrine was not just a theoretical exercise; it had practical implications as well. It influenced the way people of the time understood their place in the universe, their relationship with the divine, and the nature of the world around them. The heavens were no longer just a distant, impersonal expanse; they were a part of God’s creation, intimately connected with the spiritual life of believers.

In summary, the integration of the celestial spheres into medieval Christian doctrine represents a fascinating example of how religious thought can intersect with and incorporate scientific understanding. This integration reflected an attempt to reconcile the Ptolemaic cosmology with Christian beliefs, viewing the heavens as a testament to God’s glory and order. The celestial hierarchy, mirroring the ecclesiastical hierarchy, symbolized a divinely ordained structure of the universe, blending the physical with the spiritual in a unified vision of creation.

2°) Islamic and Jewish Philosophical Contributions:

Islamic scholars made profound contributions to the study of the celestial spheres, often through a synthesis of Aristotelian and Neoplatonic thought with Islamic theology. Figures such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna (Ibn Sina) stand out in this regard. Al-Farabi, in his works, delved into the nature of the universe, drawing upon Aristotelian physics to explain the workings of the celestial spheres. He sought to reconcile these ideas with Islamic teachings, viewing the cosmos as a well-ordered, harmonious system that reflected the unity and perfection of the divine (Nasr, 1993).

Avicenna, another towering figure in Islamic philosophy, further developed these ideas. His works on cosmology not only expanded upon the Greek understanding of the celestial spheres but also infused them with a distinct Islamic perspective. Avicenna emphasised the rationality and order of the universe, seeing in the celestial spheres a manifestation of divine wisdom and will. His interpretations were influential in shaping the Islamic view of the cosmos, portraying it as a unified, coherent system that operated according to principles that could be understood through reason and observation (Nasr, 1993).

In the Jewish intellectual tradition, figures like Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon) played a crucial role in integrating the concept of the celestial spheres with Jewish theology. Maimonides, in his philosophical works, grappled with the challenge of harmonising the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic cosmological models with the teachings of the Hebrew Scriptures. He sought to find a balance between the philosophical understanding of the universe and the theological principles of Judaism, particularly the concepts of divine creation and providence (Wolfson, 1929).

Maimonides’ approach was characterized by a careful and critical engagement with the philosophical ideas of his time. He adopted those aspects of Greek cosmology that he found compatible with Jewish thought, while providing interpretations and arguments to address potential conflicts. His work represents a significant effort to create an intellectual space where Jewish theology and Greek philosophy could coexist and enrich each other.

The contributions of these Islamic and Jewish scholars to the understanding of the celestial spheres were not confined to their respective religious or cultural spheres. Their works were part of a broader, cross-cultural dialogue that spanned the Islamic and Christian worlds. The translations of their works into Latin in the medieval period played a crucial role in transmitting these ideas to the Christian West, where they influenced later astronomical and philosophical thought.

In summary, the Islamic and Jewish contributions to the understanding of the celestial spheres represent a significant chapter in the history of astronomy and philosophy. These scholars, by engaging with and expanding upon the Greek legacy within the context of their own religious and cultural traditions, enriched the medieval understanding of the cosmos. Their works illustrate the power of intellectual exchange and the enduring quest to understand the universe in a way that harmonizes scientific knowledge with spiritual and philosophical insights.

IV. Astrology and the Celestial Spheres:

Astrology, with its intricate system of interpreting celestial phenomena, has played a significant role in human history, particularly in relation to the celestial spheres. This section explores the astrological significance of planetary movements, the concept of aspects, the role of astrology in daily life and decision-making in ancient times, and its transition to astronomy during the Renaissance.

The movements of planets within the celestial spheres have been of paramount importance in astrology. Ancient astrologers, such as those who contributed to Ptolemy’s “Tetrabiblos,” observed and interpreted these movements to predict earthly events and understand human characteristics. Each planet, moving through different signs of the zodiac, was believed to exert a unique influence. For instance, Mars was often associated with war and conflict, while Venus was linked to love and beauty. The position of these planets at the time of one’s birth was thought to have a profound impact on one’s personality and fate (Ptolemy, 2nd century).

Aspects, or the angular relationships between planets, form a core component of astrological practice. These include conjunctions, oppositions, trines, and squares, each with its own meaning and influence. For example, a trine, an angle of 120 degrees between two planets, was traditionally seen as harmonious. The philosophical implications of aspects lie in their representation of the interconnectedness of the cosmos. They reflect the belief that celestial phenomena are not isolated events but part of a larger, interconnected cosmic tapestry that influences life on Earth.

Astrology’s integration into the fabric of daily life and decision-making in ancient societies was profound and far-reaching. Historical records and artifacts from various civilizations provide ample evidence of how rulers and commoners alike relied on astrological guidance for a multitude of decisions.

In ancient Mesopotamia, one of the birthplaces of astrology, kings would not make important state decisions without consulting astrologers. For instance, the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (7th century BC) is known to have employed a group of scholars, including astrologers, to interpret omens and advise on matters of state. These astrologers would meticulously observe the skies and interpret celestial phenomena to guide the king in warfare, diplomacy, and even agricultural planning.

Similarly, in ancient Egypt, astrology was integral to both governance and daily life. Pharaohs, considered divine beings themselves, relied heavily on astrological predictions. The planning and construction of the great pyramids, for example, are believed to have been astrologically influenced, with their alignments corresponding to key celestial bodies.

In China, astrology was deeply embedded in the imperial court’s functioning. The Chinese developed a sophisticated system of astrology that linked the emperor’s fate to the heavens’ movements. The mandate of heaven, a central idea in Chinese political philosophy, was often interpreted through astrological signs. Emperors like Wu of Han (2nd century BC) would use astrology to choose auspicious dates for military campaigns and to predict the empire’s fortunes.

The ancient Greeks also integrated astrology into their daily lives and decision-making processes. Prominent historical figures such as Alexander the Great (4th century BC) are known to have consulted astrologers before major battles and during his extensive conquests. Astrology’s influence continued into the Hellenistic period, with rulers like Ptolemy I of Egypt (3rd century BC) not only patronising astrological research but also using it to govern.

In Rome, astrology was both popular and controversial. While some emperors, like Augustus (1st century BC/AD), embraced astrology, using it to legitimise their rule and make strategic decisions, others, like Tiberius, were known for their scepticism. Nonetheless, astrology remained a significant aspect of Roman culture, influencing everything from political decisions to personal life.

These historical examples illustrate the pervasive influence of astrology in ancient societies. Astrological charts and readings were not mere curiosities; they were essential tools for guiding decisions that shaped the course of history. From the planning of cities and pyramids to the timing of battles and the legitimisation of rulers, astrology’s role in the ancient world was both practical and profound, reflecting its deep integration into the fabric of societal and individual decision-making.

The Renaissance, a period of profound intellectual and cultural awakening, marked a significant transition from astrology to astronomy. This shift was exemplified by several key historical figures whose work laid the foundations for modern astronomy.

Nicolaus Copernicus, in the early 16th century, challenged the geocentric model with his heliocentric theory, positing that the Earth and other planets orbit the Sun. This revolutionary idea, presented in his seminal work “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” (1543), marked a fundamental shift in the understanding of the cosmos.

Galileo Galilei furthered this transition in the early 17th century with his telescopic observations. His discoveries, such as the moons of Jupiter and the phases of Venus, provided strong support for the Copernican model and challenged the traditional astrological view of a static, Earth-centered universe.

Johannes Kepler, a contemporary of Galileo, made significant contributions with his laws of planetary motion. Initially an astrologer himself, Kepler’s work “Astronomia nova” (1609) demonstrated that planetary orbits were elliptical, not circular as previously thought. This not only advanced astronomical understanding but also signaled a move away from the astrological interpretations of celestial phenomena.

These scientific advancements, occurring during the Renaissance, were pivotal in shifting the focus from astrology to astronomy. The adoption of the scientific method and the emphasis on empirical observation led to a more rigorous, evidence-based understanding of the cosmos, diminishing the role of astrology in scientific discourse.

In sum, astrology’s relationship with the celestial spheres has been a journey through history, from guiding daily decisions and shaping philosophical thought to evolving into the modern science of astronomy. This journey reflects humanity’s enduring quest to understand the cosmos and our place within it.

The journey through ancient astrological cosmology highlights a rich interplay between astronomical observation and philosophical, theological thought. From its origins in Mesopotamia and Egypt to its development in Greek philosophy, and from its integration into medieval religious thought to the shift towards modern astronomy during the Renaissance, this exploration underscores humanity’s enduring quest to understand the cosmos.

Key developments include the geocentric model, the role of astrology in ancient societies, and the transition to a scientific understanding of the universe. The legacy of ancient astrological cosmology endures in modern culture, reflecting a deep human desire to find meaning in the cosmos.

Future scholarly research offers vast opportunities, including cross-cultural studies of astrological cosmology and its socio-political impacts, as well as interdisciplinary approaches combining astronomy, history, philosophy, and cultural studies. This field not only delves into historical beliefs and practices but also offers insights into our continuous pursuit of understanding the universe and our place within it.

References and further reading:

Aquinas, T. (13th century). Summa Theologica. Aristotle. (4th century BC). Metaphysics. Ashurbanipal. (7th century BC). Library of Ashurbanipal. Augustus. (1st century BC/AD). Res Gestae Divi Augusti. Bobrick, B. (2005). The Fated Sky: Astrology in History. Simon & Schuster. Cornford, F.M. (1997). Plato’s Cosmology. Hackett Publishing. Copernicus, N. (1543). De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. Dante Alighieri. (14th century). Divine Comedy. Galilei, G. (17th century). Sidereus Nuncius. Grant, E. (1996). The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. Hildegard of Bingen. (12th century). Scivias. Hoskin, M. (1999). The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. Jones, A. (2017). Hipparchus. Cambridge University Press. Kepler, J. (1609). Astronomia nova. Krupp, E.C. (1997). Skywatchers, Shamans & Kings. Wiley. Kuhn, T.S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press. Lindberg, D.C. (2007). The Beginnings of Western Science. University of Chicago Press. Nasr, S.H. (1993). An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines. State University of New York Press. Philo of Byzantium. (1st century BC). On the Seven Wonders. Ptolemy. (2nd century). Tetrabiblos. Ptolemy I of Egypt. (3rd century BCE). Ptolemaic Dynasty Records. Rochberg, F. (2004). The Heavenly Writing. Cambridge University Press. Tester, S.J. (1987). A History of Western Astrology. Boydell Press. Toomer, G.J. (1998). Ptolemy’s Almagest. Princeton University Press. Wallis, R.T. (1972). Neoplatonism. Charles Scribner’s Sons. White, G. (2008). Babylonian Star-lore. Solaria Publications. Wolfson, H.A. (1929). Crescas’ Critique of Aristotle. Harvard University Press. Wu of Han. (2nd century BC). Records of the Grand Historian.

Thank you for reading.

Fuel my caffeine addiction and spark my productivity by clicking that ‘Buy me a coffee’ button—because nothing says ‘I love this blog’ like a hot cup of java!

Buy Me a Coffee

Your Astrologer – Theodora NightFall ~

Your next 4 steps (they’re all essential but non-cumulative):

Follow me on Facebook & Instagram!

Subscribe to my free newsletter, “NightFall Insiders”, and receive my exclusive daily forecasts, weekly horoscopes, in-depth educational articles, updates, and special offers delivered directly in your inbox!

Purchase one of my super concise & accurate mini-readings that will answer your most pressing Astro questions within 5 days max!

Book a LIVE Astro consultation with me!

L’article The Celestial Spheres: A Philosophical Exploration of Ancient Astrological Cosmology est apparu en premier sur NightFall Astrology.