The idea Nestled deep in the Gradys Creek Valley on the southern side of the McPherson Range, which separates New South Wales from Queensland, lie several properties, a small school and a community hall. There is no communal area...

The idea

Nestled deep in the Gradys Creek Valley on the southern side of the McPherson Range, which separates New South Wales from Queensland, lie several properties, a small school and a community hall. There is no communal area or village, but it is known as The Risk. The name came from the first settler who decided to take a risk to ride over the mountain.

The area’s residents had constantly agitated for a direct road route connecting them to Queensland over the range ever since the North Coast Railway passed through the area in the 1930s. During the rail line construction between 1926 and 1930, it was possible to drive between the states following the railway cuttings. But that stopped when the railway was opened.

Summerland Way in the early days

Summerland Way in the early days

The residents were only a hop, skip and a jump from the border and a direct route to Brisbane if only they had a road. But they had to travel south down the valley on the narrow winding road, west along Summerland Way and north on the Mount Lindesay Highway, which ran from Brisbane to Tenterfield – a circuitous route around the range over the least forgiving gap adding many kilometres to their trip.

In time, they joined the chorus for a direct route over the range.

The McPherson Range forms the eastern section of the New South Wales-Queensland border and has three gaps. Early settlers moved cattle crossing the range at Richmond Gap, a prominent feature in the local community. Richmond Gap is very advantageous for travelling to and from Brisbane as it is directly in line with Grafton, Casino, Kyogle and Brisbane.

In 1932, the residents of the Richmond Valley, including the major centres such as Kyogle, officially made representations for a direct route to Brisbane via the Richmond Gap. The local councils and chambers of commerce on both sides of the border supported a road link. Successive New South Wales state governments considered their proposal. However, they couldn’t or wouldn’t decide whether to build a road. Finally, in 1967 they promised a feasibility study to find the best route between Kyogle and the border to be completed within 18 months, with a possible start on construction within three years.

Unfortunately, that optimism was short-lived when the Minister announced in 1969 that they wouldn’t build a road for at least 15 to 20 years.

Fortunately, a guy called Jack Hurley lived in the area. He grew up under the shadows of the McPherson Range. His parents wanted him to be a teacher, but after spending much time in the bush with his father working and driving machinery trucks, he decided to be a mechanic. He married after the outbreak of WWII and said he would join up for military service if the Japanese joined the war.

After Army service out of Sydney, Jack returned to Kyogle and started a business with Alan Brown to supply parts and service trucks. They called the company Brown and Hurley, now one of Australia’s largest truck and trailer dealerships. What set Hurley apart from everyone else, and helped him in his business, was his determination to see a dream become a reality.

Jack Hurley.

Jack Hurley.

Jack was heavily involved in local community work. He founded the Kyogle Lions Club, which provided crucial voluntary support to locals. In the late 1960s, the timber industry was declining, and the dairy industry was in trouble after losing the European common market for butter.

Jack was also President of the Summerland Way Committee. While there was a route to Brisbane, it was in appalling condition, with little maintenance funds available to improve it. The club believed a shorter road to Brisbane would benefit the area. Even without political support at the state level, Hurley and the Kyogle Lions Club still decided to promote the need for a better road.

The road to Brisbane for Kyogle and Richmond Valley residents in the early years.

The road to Brisbane for Kyogle and Richmond Valley residents in the early years.

The club were looking for a worthwhile community development project. They decided to push for the road to be built. But at that stage, they had no intention of building the road, just providing the necessary support, analysis and representations.

Members began reconnaissance trips in 1969 through the bush to work out a grade over the range.

Jack’s resolve was hardened further after the Shire Engineer told him he was wasting his time.

At the time, Jack managed to meet members of Queensland’s Beaudesert Lions Club while he stopped for dinner on a trip back from Brisbane. Jack arranged to meet them at the border for lunch when they reached it with their fieldwork. It was here they forged a partnership to work together.

On the New South Wales side, the McPherson Range is very steep, with many gullies and spurs, covered in thick rainforest. Local foresters and forestry staff with extensive road construction experience in the area were interested in the proposal. As part of their roading program through state forest adjoining the border, they had already built a fire trail along the range on the western side of Gradys Creek to the border. It was an attractive proposition to upgrade their existing trails as it involved no bridges, few culverts and was well away from the railway line. However, it required 21 kilometres of road, climbed about 540 metres above the Richmond Gap and didn’t serve the needs of the local people.

Instead, the club built a rough firebreak over a more direct route after more fieldwork. They invited over 200 people to a public meeting at Richmond Gap on 26 October 1969. It was an opportunity to see first-hand what could be achieved. Those from the New South Wales end walked the three miles from Cougal on the firebreak to the gap.

The resolution from the meeting was to lobby the New South Wales government to build a road. The Queensland Main Roads Department had already indicated a willingness to cooperate in getting a road connecting the two areas.

But when they organised an inspection day for government officers and local councillors, all it did, however, was scare them as the grades were steep and the track was rough. At one section, 4wd’s had to be winched up the slope!

Winching a 4wd

Winching a 4wd

Not to be deterred, Jack and the Lions Club decided to build the road themselves across the range connecting the existing Shire roads at Cougal on Gradys Creek in New South Wales with the Beaudesert Road at Running Creek on the Queensland side as a community development project.

They had to walk through areas that had a fire recently that supported a dense regrowth of lantana, tobacco bush and stinging nettles. After borrowing an altimeter, they determined the height of the Richmond Gap and marked trees at the height they needed to be on the ridges. They managed to mark a route, and the Forestry Commission’s road survey team checked the line, improved the grade and alignments where necessary, and finished with a marked centre line. They estimated the road could be built at the cost of $26,000.

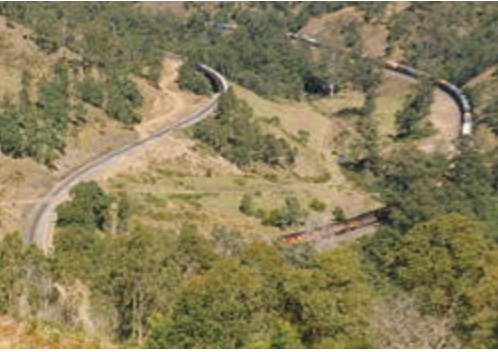

The Loop

The Loop

To understand the difficulty of the terrain, one only has to appreciate the extraordinary work done to get the railway through the range. First, they had to build a tunnel one and a half kilometres long through the range and under the state border. Then construct a complete loop through two more tunnels over a high bridge. The loop lowered the line by 65 feet. Without this elevation drop, one extremely long tunnel would have had to be built to get past the range.

Lions Road travels above the spiral loop tunnel, and during construction, there was always a worry that a rock may roll down the hill onto the railway line.

Construction

When it was time to start construction, the Lions Club only had $2,000 and an old front-heavy Fowler dozer donated by local business Brown and Hurley. It was challenging to work in such a steep country. Jack’s ability to raise awareness of the project and help from local businesses was legendary. A local earthmoving contractor with considerable experience in building roads for the Forestry Commission offered his D8 Cat dozer for 80 hours to allow them to build the road at a standard for normal cars. Fortunately, it also came with a very experienced dozer operator.

The club then went into overdrive to seek donations for the road. Shell provided 20 tons of fuel; local councils donated culverts; local transport companies delivered the culverts; and local sawmiller Mel Hogan provided necessary timber and his D6 dozer. A fund was opened for public donations, which raised $5,000 and club raffles at a local hotel in Kyogle raised another $5,000.

The D8 arriving to start work

The D8 arriving to start work

An old Blitz truck with a winch was donated to transport the big culverts into place before the road formation.

The new road after heavy rain.

The new road after heavy rain.

With work underway, there were many challenges, not least the heavy rain. The early 1970s were very wet years. With new earthworks and batters exposed, they continually washed away easily around culverts. One night they had an overnight storm of 13 inches, and the first three crossings and the approach to the river disappeared entirely.

They ploughed on and managed to build the road with the help of many supporters, all organised by Jack with his friendly and persuasive manner. Members of the Lions Clubs and their families worked tirelessly every weekend to install cattle grids.

Transporting a large culvert to lay on the new road construction.

Transporting a large culvert to lay on the new road construction.

Ultimately, the completed road was 11 kilometres long with 56 sets of culverts, three bridges and 12 cattle grids.

It was a truly remarkable achievement, particularly for the local community.

The Tick Gate and Rabbit Fence

Jack and his fellow organisers overlooked the problems of getting through the border fence until the last minute. As the road construction got closer to the top of the range, Jack had assumed that when he got approval from the Tick Board to cross the border, they also got approval from the Rabbit Board. Instead, they had to seek permission to open and lower the border fence from the Moreton Rabbit Board. They received support on the proviso the landowner on the Queensland side of the fence had to accept responsibility for the closing of the gate and the cost of eradicating any rabbits that went over the border.

Cutting the bridge timber.

Cutting the bridge timber.

It was not surprising that Jack and the Lions Club had to deal separately with each Board. The fence they controlled and maintained along the McPherson Range was a double fence to control the movement of rabbits into Queensland and cattle ticks into New South Wales. Therefore, one Board was Queensland based, and the other was from New South Wales.

Cattle tick was first discovered in Australia in 1872 when a herd of infected Brahman cattle were brought from Indonesia to Darwin for slaughter. However, it took only 20 years for the ticks to spread throughout Queensland. In 1898, there were reports of cattle ticks near the New South Wales border town of Tweed Heads, and by 1906, the tick was found at Kyogle and Kempsey. A Royal Commission was held in 1918 into the impact of cattle ticks in New South Wales.

The New South Wales cattle tick program was introduced in 1920 to prevent cattle ticks from entering the state from Queensland and to detect and eradicate infestations. Returned soldiers were employed as inspectors with quarantine areas from Kempsey to the border. Plunge dipping or spraying of cattle was compulsory for cattle entering quarantine zones.

Tick gates were on the Queensland-NSW border in the 1950s. The Tick Board agreed to operate the gate 24 hours on Lions Road, and the first gatekeeper in 1971 was Barney Rowe. Until the 1970s, vehicles were checked at the gates to stop tick-infested cattle from entering NSW. It was a controversial practice, especially as horses, a minor and lower-risk spreader of the tick, had to be dipped as well.

After construction

A gravel road was completed within two years and officially opened in 1973. It was gradually bituminised and completed in 2005. The sealed Lions Road sees over 100,000 cars each year and is recognised as being one of the most scenic drives on Australia’s east coast.

Local farmers and Lions members continued to beautify sections of the road. They worked voluntarily, which shows excellent community spirit and pride in such a remarkable achievement against the odds. Jack’s passion for the road endured long after its completion. He organised the rehabilitation of sections, replacing vegetation that was damaged during construction.

One of the bridges on the Lions Road.

One of the bridges on the Lions Road.

The road allows the public access to a lookout to view the railway loop, the only such construction in the world. It is a bonus to see a train pass through the tunnel and on the loop from the lookout.

Lions Road is the biggest project ever undertaken by any Australian community service club. It is now a beautiful and popular tourist road that provides a much shorter route from Richmond Valley to Queensland. It is very popular with motorcyclists.

For nearly 40 years, Jack was Chairman of the Lions Road Committee. He lobbied politicians, government departments, and businesses to get the job done. He also organised working parties and worked alongside them. He was tireless on the project and in Kyogle to improve conditions for its residents. He was awarded an OAM for community service in 1982.

Jack Hurley.

Jack Hurley.

He wrote two books, one of which was “The Lions Road – the story of a dream and the way it became a reality”.

The road celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. You can watch a short video ABC made about Lions Road here.

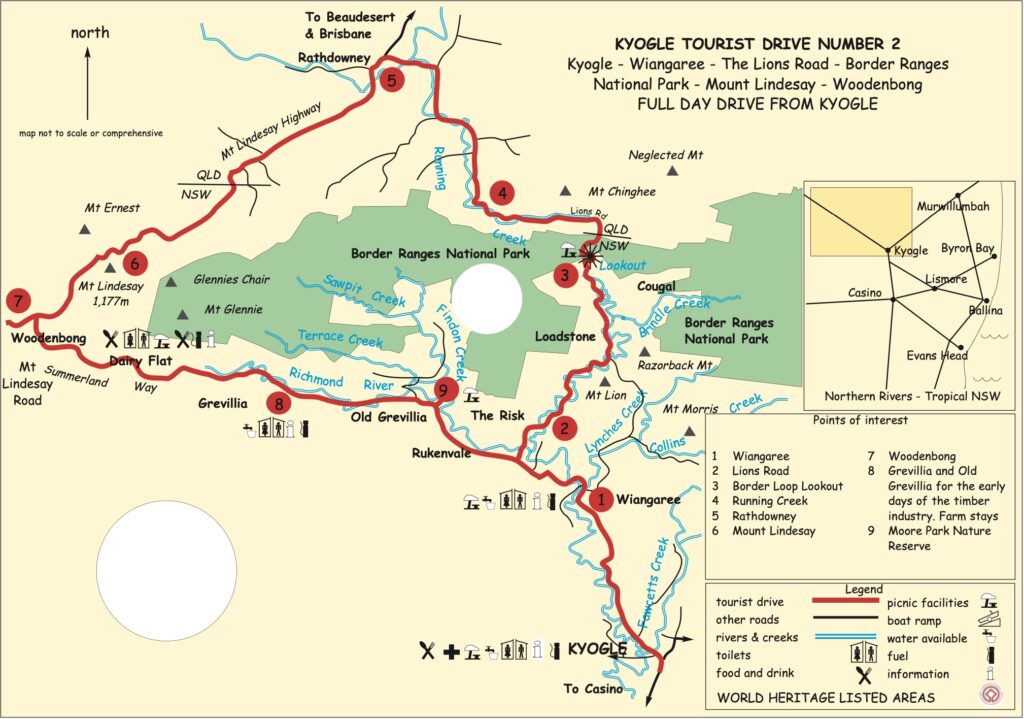

Map showing the Lions Road as part of a tourist drive in the area. The Lions Road is roughly the section between 2 and 4 on the map.

Map showing the Lions Road as part of a tourist drive in the area. The Lions Road is roughly the section between 2 and 4 on the map.