“By members of the Desert Mounted Corps and friends, to the gallant horses who carried them over the Sinai Desert into Palestine, 1915-19. They suffered wounds, thirst, hunger and weariness almost beyond endurance, but they never failed. They did not...

“By members of the Desert Mounted Corps and friends, to the gallant horses who carried them over the Sinai Desert into Palestine, 1915-19. They suffered wounds, thirst, hunger and weariness almost beyond endurance, but they never failed. They did not come home”.

Inscription on a monument erected by returned soldiers in Sydney

As we stop tomorrow to remember those who fought in wars but didn’t return home, I thought I would share an Australian story about a unique horse breed in Australia.

The story began at a time when horsepower did everything. It was a time when a good horse was valuable and provided status in the community. In the first 30 years of European settlement in Australia, about 3,000 riding and draught horses were used for farming and moving goods. Breeding horses for our needs became an important industry.

Around 1816, the first shipment of horses left New South Wales for Batavia and India. Many ships advertised for horses as part of their cargo. The following year, 25 horses travelled on the Fame to Batavia. The Lynx was after a matching pair of bay, brown or black geldings 14.2 hands high for carriage work and a brown riding gelding for a customer in Calcutta. In 1818, the Laurel took 23 horses to Batavia, and the Pilot took 34 from Hobart. In 1835, traders sent more horses to Madras.

By the 1840s, there were many horse traders and a strong export market to India. It coincided with the fall of the Sikh kingdom in the north-west frontier region of India called Punjab after the death of their ruler Ranjit Singh in 1839 and the subsequent rise of disorder and internal ructions between competing factions for power and influence even as the Sikh army increased its numbers from 29,000 to 80,000.

In response, the British East India Company began increasing its military strength adjoining Punjab. The British believed the Sikh Army, without strong leadership to restrain them, was a threat to their territories along the border with Punjab. War followed the heightened tensions.

(Left) The 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons at the Battle of Mudki, 1st Sikh War, 1845. Painting by Ernest Crofts.

Sir Walter Gilbert was an army officer in the British East India Company who commanded a division at the battles of Mudki and Ferozeshahr during the first Anglo-Sikh War in 1845-6 and another in the 1849 battles of Chilianwala and Gujrat in the second Anglo-Sikh War. He advanced his reputation by pursuing the Sikh’s Afghan allies up the Kyber Pass.

Each battle during those two wars saw vigorous cavalry actions on horseback backed up by horse and field artillery. They were hard fought on vast flat plains broken by scrub and chocked by rising dust in the scorching heat. The Indians had been tremendous horsemen for centuries – claiming to be one of the oldest horse cultures in the world, so it was no surprise that the horse played a major role in the conflicts.

After those wars, the British Army wanted draught horses for pulling guns and quality cavalry remounts for the Punjab region, now part of Pakistan. Gilbert oversaw the British Army’s Horse Commission in India and recommended Australian horses as the best for their needs. They were recognised for their looks, endurance, agility and courage.

Initially, its breeding origins were in New South Wales, and they were known as New South Walers. However, they soon became known universally as the Walers.

What are Walers?

Many varieties of horse breeds were brought to the Australian colonies from across the world in the nineteenth century. They came from India, the Cape Horses from South Africa, the Timor Pony, Thoroughbred, Welsh Pony, Sumba, Chile horses, Arab, Clydesdale and Percheron, and many more.

Governors of each colony encouraged the breeding of horses to meet their transport needs. Owners of large properties were breeding horses by the thousands. They were looking for a horse that could thrive in a big country with good bones, hard hooves, endurance, the ability to thrive on low-quality feed and possessed wisdom. Keen breeders wanted the best of the best, using stayers raised in rugged country to develop strong survival traits.

As a type of horse, the Waler filled a broad concept that was difficult to define. It was essentially an Australian-bred bush horse. It was not a purebred of one breed. Many types were created, from heavy through to pony, to meet the local demand – riding horses, gun horses, light draught, heavy draught, packhorses and polo ponies were all known as Walers. It was a breed in the making “using the best of the best when horses were at their best”.

The practice of cross-breeding from the available breeds resulted in a versatile working horse with good weight-carrying capabilities, speed, endurance, and the ability to thrive on native pastures.

Initially, breeding filled a considerable demand for domestic needs of the colonies – coach, carriage and post horses. But as the strong export trade in remounts for the British Army in India developed, the Waler was recognised as the finest cavalry horse in the world.

The early horses that went to India were surplus Cobb and Co. horses. These horses were called coachers, a cross between a trotter and a draught horse. They were between 14.5 and 16 hands tall, wide-chested, strong and muscular. They were known for their speed and stamina.

By the 1860s, about 40,000 horses a year were sold to the British Army in India. Many Northern Territory and South Australian stations were leased solely for horse breeding. Over the next decade, the numbers increased to 50,000, and exports started to other countries such as Japan, the Philippines and Indonesia. As a result, over half a million Walers were exported for armies worldwide. Waler ponies were also popular in India as the Rajahs, and the English bought them for polo.

War heroics

Right through history, from Ghengis Khan to medieval knights, armies have used horses as war machines. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Australian colonies could instantly horse its mounted divisions because they had a ready supply, in great numbers, of the perfect cavalry horse. This was the case at the outbreak of the Boer War, where the British sought infantry troops from the Colonies to assist. Australia sent a mounted infantry and 16,000 horses, a forerunner of the light horse. Unfortunately, horse welfare was not paramount during the war, and of the 469,000 horses purchased from around the world by the British Army, 326,000 died due mainly to disease and poor horse management.

Because of the horrific loss of horses, the British Army reorganised its veterinary and remount services after the war.

After the Federation of Australia, military matters became the responsibility of the Commonwealth Government, which organised an army made up of volunteers who were militias or part-time soldiers and a small contingent of permanent soldiers. Officers had to supply their own horses at their own expense and were paid an allowance.

(Right) Transport horse holders waiting to embark their mounts at Port Melbourne, WWI. Photo Australian War Memorial.

After the outbreak of WWI, Australia raised four Light Horse Regiments of 600 men. They sailed to Egypt with 5,000 horses. In 1915, a further nine Light Horse Regiments were raised, and the Australian Imperial Force’s first remount units were formed. After Gallipoli, where very few horses were needed, the AIF returned to Egypt, where the Light Horse Brigades became the backbone of the Desert Mounted Corp. All movement of supplies and troops away from railway lines was by horse and camel.

One pivotal factor in the desert campaigns was that, despite the variety in the types, the Walers were all from thoroughbred sires. It was here that the Waler was recognised for its distinguishing characteristics.

One of the most courageous and internationally recognised war time feats was that of the 4th and 12th Regiments of the Australian Light Horse at Beersheba on 31 October 1917. Beersheba was a defensive position occupied by Turkish troops who thought that being two to three days ride away from Australian lines across a waterless, sandy wasteland made them immune to attack. However, the Australian military commanders realised that controlling Beersheba was the key to ousting the enemy from the Middle East. So they decided to chance their arm.

After a full night’s march and a day of fighting without water, the Aussies appeared in front of the Turkish defensive position in a line of advance. The Turks expected them to stop and fight and so set their machine gun sights out to their limit. The horses cantered forward until the Turks opened fire. But instead of dismounting, the soldiers spurred their dehydrated mounts into a headlong charge across the bullet ridden plain. The Turks failed to lower their gun sights and very soon the cavalry soldiers were beneath the hail of bullets.

The Australian troops quickly galloped over the Turkish trenches and into Beersheba, helping the AIF win the battle as it marked the beginning of the end for the Turks in the Middle East. One laconic trooper attributed the charge’s success to desperately thirsty horses that couldn’t be held back once they smelled water at the Turk’s stronghold.

London’s War Office directed troopers to hand in their horses at the war’s end. The excuses were quarantine restrictions, insufficient ships, and costs that meant the Walers could not return to Australia. While there are no official figures, it is believed that many horses were transferred to Britain or India for the Australian government to get credit for reducing its war debt to Britain. In France, most were either sent to a remount depot for sale to farmers in England, sold directly to farmers in France and Belgium, or, tragically, sold to butchers in those two countries.

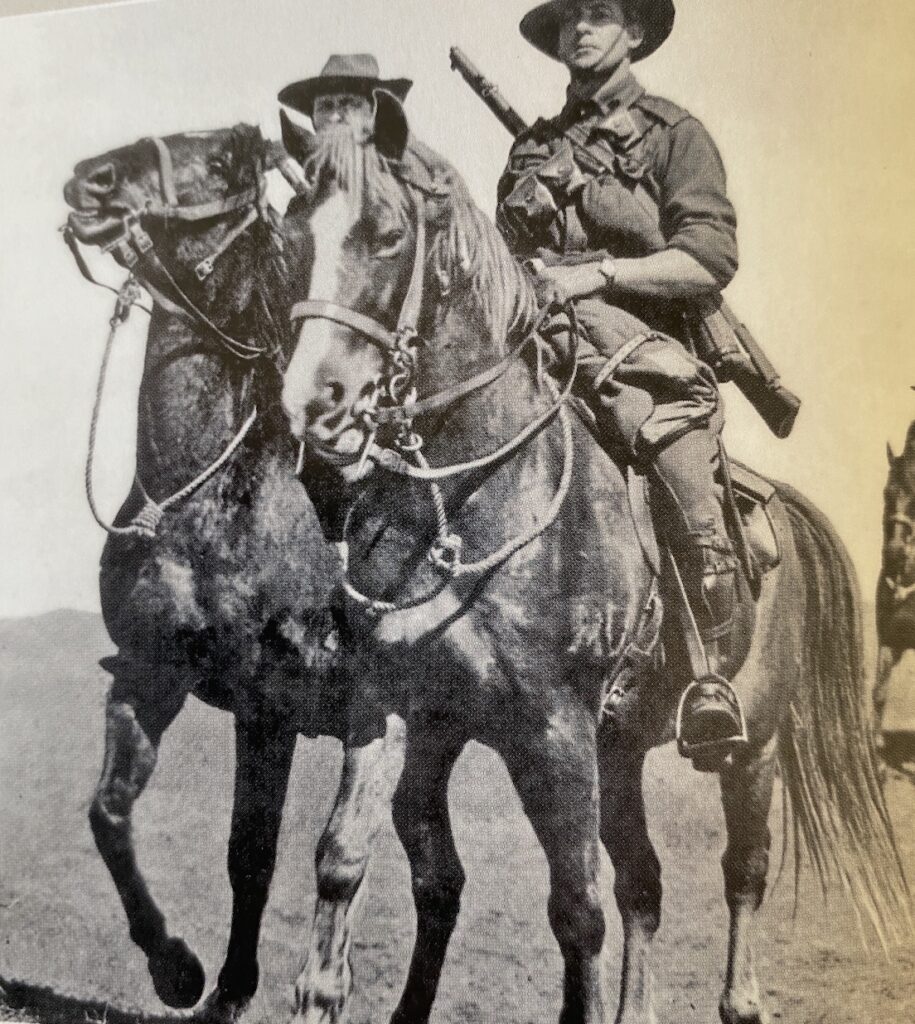

(Left) Light Horse cavalrymen, WWI.

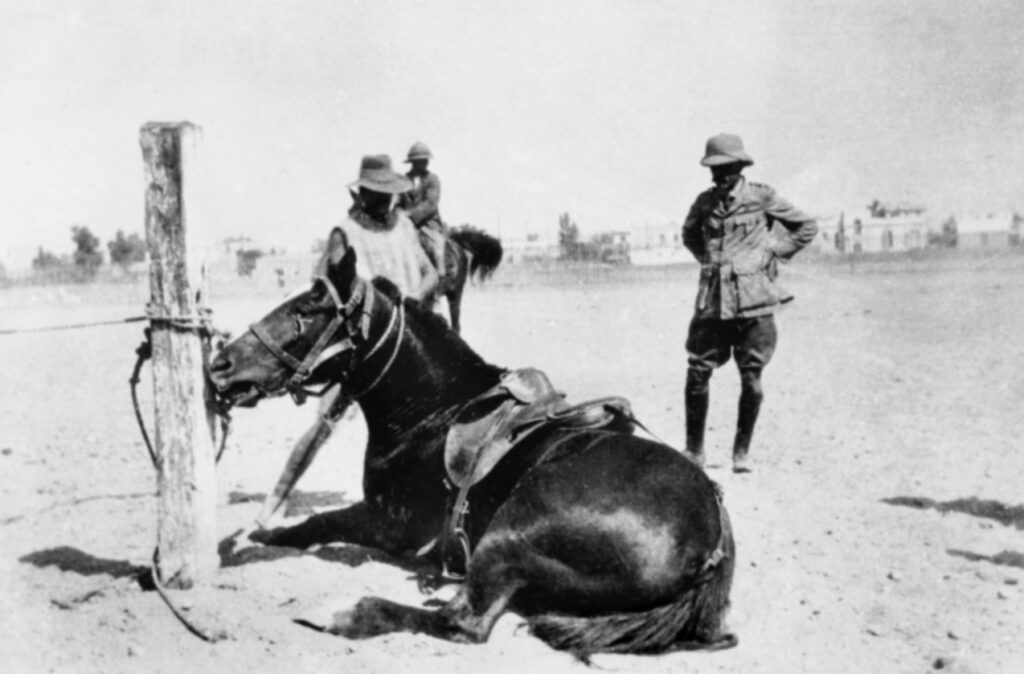

It was a different story in the desert. According to Roland Perry in his book The Australian Light Horse, the relationship between man and his equine mount was so strong they preferred to put the horses down than let them have another owner or be slaughtered for meat. As a result, many horses were handed into the Remount Depot and led away by men of the 6th Regiment and machine-gun squadron.

It was indeed a sad and tragic end to these gallant horses and a reflection of the indifference of war officials far removed from the action who had no idea of the strong bond the servicemen had with their mounts.

Banjo Paterson, our most famous poet, spent two years nurturing, breeding, preparing, training and breaking in the mounts in Egypt, a role not widely known. He was disgusted with the War Office directive. He and the troopers witnessed the way locals in Egypt and Palestine treated their horses – how they were emaciated and flogged and didn’t want the same fate for their beloved Walers.

(Right) Captain Andrew Barton ‘Banjo’ Paterson (right) of the 2nd Remounts, AIF. Photo Australian War Memorial.

Yet, while Paterson wrote about his experiences at the remount depots in Egypt and Palestine, he didn’t break into verse over what happened to the beloved Walers.

However, Trooper Bluegum (his real name was Oliver Hogue) wrote a poignant poem, The Horses Stayed Behind, highlighting the horse’s cruel fate and their rider’s motivation when they couldn’t bring them home with them. Here are his third and fourth verses:

I don’t think I could stand the thought of my old fancy back, Just crawling round old Cairo with a Gypo on his back, Perhaps some English tourist out in Palestine may find, My broken-hearted Waler with a wooden plough behind. No, I think I’d better shoot him and tell a little lie, “He floundered in a wombat hole and then lay down to die,” Maybe I’ll get court-martialled, but I’m damned if I’m inclined To go back to Australia and leave my horse behind.Unfortunately, shortly after penning his poem, Hogue died of the Spanish flu in 1919. While the killing of their horse was illegal, the horsemen felt strongly about leaving them to a terrible life. For the army, it didn’t matter. The horses were worth something, alive or dead. If a horse was over 12 years old, it was officially put down, and its parts – hides, manes, tails and shoes – sold off.

It was such an undignified end to a courageous creature that helped free the world of tyranny. At least those that died at the hand of their trooper had a good feed and a last ride before being shot, not needing a second bullet. However, the familiar rifle crack haunted those men to their graves.

The only Waler to return to Australia was Major-General Sir William Bridge’s charger Sandy, which didn’t see any action. Bridges was killed at Gallipoli, and Sandy spent time in Egypt and France before returning to the Central Remount Depot at Maribyrnong in Melbourne. His head and neck were mounted and displayed at the Australian War Memorial for many years.

During WWII, no horse-mounted units were raised for overseas service. However, when a Japanese invasion of our north was feared, a surveillance unit called the North Australia Observer Unit, or Nackaroos, was formed, and they used about 600 Walers.

(Left) Sandy’s head. Photo Australian War Memorial.

Some breeding places

As I travelled around Australia, I learnt of many areas where the Walers were bred for export. After being first bred in New South Wales during the early settlement period, horse owners and breeders across Australia cross-bred them to form different types to meet specific markets that became part of the Waler horse breed.

For example, in 1840, the Western Australian Land Company purchased 103,000 acres about 12 kilometres north-east of Bunbury to create an English-style village populated by settlers. It became known as Australind, a combination of Australia and India in recognition of its intention to breed horses for the British Army in India, which was also carried out at nearby Cervantes and Northampton.

In 1876, an ex-British Army officer started breeding quality polo and cavalry horses at Madura Station on the Nullarbor Plain to sell to the British Army in India. The site was chosen as it was one of the few in the area with free-flowing bore water. The horses were shipped to India from Eucla.

The son of one of Maryborough’s pioneers, Harry Aldridge, and George Dicken obtained two pastoral leases in 1879 at Eurong and Indian Head on Fraser Island. Twenty horses, including the rare Suffolk Punch breed, Arab and Clydesdales, and 40 head of cattle were barged to the island. They developed a business partnership to cross-bred Walers as gun carriage and remounts for the Indian Army.

It is not known for how long the horse breeding operations lasted. One ship load of horses did sink south of Sandy Cape and some of the horses swam back to Fraser Island to run wild in the scrub. When Aldridge and Dicken gave up their run, they left behind horses that had escaped and eluded recapture. The legacy was the small population of brumbies that roamed on the island until their removal and shooting in the early 1990s. The workhorse influence could be seen in the weight and strength of the brumbies’ legs and hooves. Horse experts believed the Arab strain could be detected in the brumby foals.

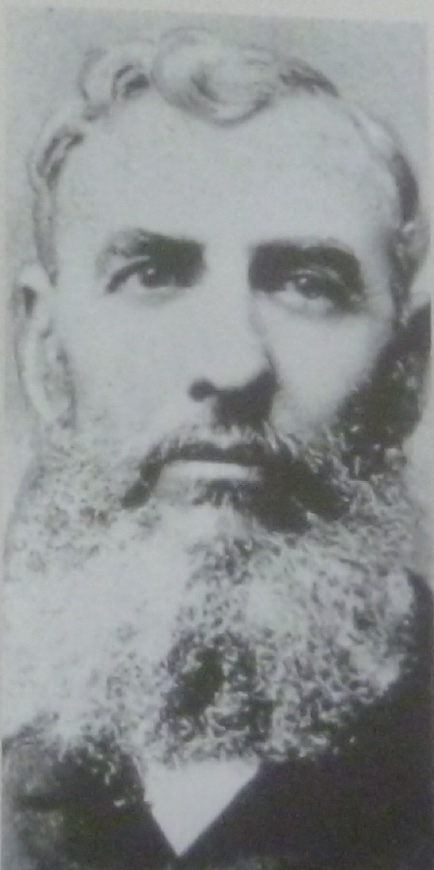

(Right) Harry Aldridge

William Titmarsh was a cattle and horse dealer who learned his craft while working for Hardings in Ipswich, Queensland. He bought land near Maryborough on the Mary River in 1907 to breed Walers. He focused on producing types suitable for hauling heavy gun carriages called “Galloping Gunners” for export to India.

Where are they now

With the phasing out of the export remount trade in the 1940s and the onset of mechanised transport via the internal combustion engine, the commercial breeding of Walers rapidly declined. Some breeders destroyed their stock. Others abandoned them. By the 1960s, the Waler was virtually gone. Recreational and competition riders favoured the more refined purebred horse such as Thoroughbred, Arab and Quarter horses rather than the old-fashioned, heavier-boned colonial breed with no studbook.

Fortunately, Walers were left to breed true, which they successfully did after many generations without crossing out. But because there were no studbooks, they were in danger of extinction. We are fortunate that DNA tests have proved they are their own breed.

(Left) Bogong Brumbies. Photo Donna Crebbin.

Many people now hear of brumbies in national parks as destroyers of the “fragile” environment that must be eradicated or removed. They include the brumbies of the high country at the Bogong High Plains in the Alpine National Park and Fraser Island.

The modern brumbies running on Young’s Tops and the Pretty Valley area are direct descendants of a commercial mob established by Osborn Young in the 1880s on his Bogong High Plain’s run. He was a horse breeder and cattleman who ran over 1,500 horses, breeding Walers for overseas markets.

Young and the McNamara family used their runs to breed Waler types. They were branded and moved off the tops for winter, with bloodlines kept fresh with new stallions. As the trade in horses declined, the number of horses diminished. The remaining horses in the high plains went wild and became the brumbies of today. Sandy, as mentioned earlier, came from the Bogong High Plains.

When the whole of Fraser Island was declared a national park in 1992, the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) were obsessed with the erosion of the first sand dunes and the ocean beach. They believed the brumbies on the island were causing the damage to the beach and had to go. This is despite regular spring tides, cyclones and heavy seas washing away huge amounts of sand at a moment’s notice, and the brumbies preferring the sweet grass on the headlands and off the beach front.

The calls to remove brumbies on the island were first made in 1978, not long after the northern third of the island was declared a national park. But under extreme public pressure, the QPWS quickly changed their strategy to the sterilisation of stallions to allow for the gradual decline, as the debilitating effect of inbreeding would eventually lead to their extinction.

(Right) Brumbies on Fraser Island.

According to the pioneer and long-time Happy Valley resident on the island, it didn’t take long for the QPWS to start culling brumbies from Eli Creek to Indian Head when they gained full management control of the island in 1992. The Fraser Island Defenders Organisation supported the cull, and it is alleged they provided spurious claims to QPWS that brumbies were destroying pandanus palms shoots, attributed to a quote from Walter Petrie in 1913.

Then Environment Minister Dean Wells in 2014 said the culling and removal of the brumbies was a “good result for the horses and a good result for Fraser Island”. However, the rapid change in the fortunes of the dingo, a predator at the top of the food chain on the island, has taken a turn for the worse since the brumbies were removed, with some brazenly attacking humans.

These brumbies, the remnants of Australia’s great breed of Walers, are threatened in the name of preservation in national parks. Uncaring bureaucrats and “experts” far removed from the natural domain these brumbies inhabit, decided their fate with a stroke of the pen and without proper public consultation. Little recognition or regard was given to one of the country’s best export commodities and which forms part of a unique and important cultural heritage. While preoccupied with killing brumbies, they ignore other feral animals such as pigs, cats and foxes causing much more environmental damage.

The last sad word

The Waler, once lauded as the greatest cavalry horse in history has become an anachronism and is almost extinct.

In some ways, the Waler is no different from the iconic Aussie digger who accomplished many achievements in war way above their station. They showed that they were way more than a match for their enemies through pure determination, grit and unconventional survival instincts. The Waler, without its noble breeding records, never stood a chance in polite horse company, yet it played a pivotal role in the success of the British Empire during many battles.

(Left) The 12th Horse Light Regiment training at Holsworthy, NSW 1915. Photo Sydney Mail.

They had many traits of other breeds combined into one. The agility, hardiness and courage from the Cape Horses, and Timor and Welsh ponies; the strength, gentle nature and power from the Percheron and Clydesdale draught horses; a regular gait, hard hooves and iron legs of the Coaching breeds such as Cleveland Bay and Norfolk Trotters; and finally, they had speed, endurance and well-formed joints from the saddle-horse breeds such as the Thoroughbreds and Arabs.

They took men into battle, and they never failed them. The living descendants of the magnificent animals deserve to be protected. The Waler is a rare Australian horse breed that must not disappear.

I SPOKE TO YOU IN WHISPERS Neil Andrew I spoke to you in whispers As shells made the ground beneath us quake We both trembled in that crater A toxic muddy bloody lake I spoke to you and pulled your ears To try and quell your fearful eye As bullets whizzed through the raindrops And we watched the men around us die I spoke to you in stable tones A quiet tranquil voice At least I volunteered to fight You didn't get to make the choice I spoke to you of old times Perhaps you went before the plough And pulled the haycart from the meadow Far from where we're dying now I spoke to you of grooming Of when the ploughman made you shine Not the shrapnel wounds and bleeding flanks Mane filled with mud and wire and grime I spoke to you of courage As gas filled the Flanders air Watched you struggle in the mud Harness acting like a snare I spoke to you of peaceful fields Grazing beneath a setting sun Time to rest your torn and tired body Your working day is done I spoke to you of promises If from this maelstrom I survive By pen and prose and poetry I'll keep your sacrifice alive I spoke to you of legacy For when this hellish time is through All those who hauled or charged or carried Will be regarded heroes too I spoke to you in dulcet tones Your eye told me you understood As I squeezed my trigger to bring you peace The the only way I could And I spoke to you in whispers......