(Photo of woman in wheelchair, playing sport. She is smiling. Text reads: "Inspiration and objectification of people with disability - a resource for teachers and parents.") A few weeks ago I received a message from a regular blog...

(Photo of woman in wheelchair, playing sport. She is smiling.

Text reads: "Inspiration and objectification of people with disability -

a resource for teachers and parents.")

A few weeks ago I received a message from a regular blog reader, Sue.

Sue asked me if I knew of any resources for parents and teachers that teaches young people about the impact of inspiration and objectification on people with disability. She and a friend wanted to see something written from the perspective of a disabled person, that was "informy, rather than blamey". She wanted it to be in palatable language for a broad audience.

Sue told me about her little girl Eliza, who has a disability.

"Eliza is little for age, self propels a wheelchair better than Captain Risky, and has little time for people her try to step across her. As a result, she has heard it all " wow she's so clever with her wheelchair" "look a baby in a wheelchair" "poor little girl" "makes you realise how good my life is when I see your daughter" "I wonder if she'll out live you?" "Is she terminal?" "Hello little girl, you are so brave.

"I can only interpret what I see on Eliza's behalf and as far as she is concerned, she is 5 loves kindy, her big brother, swimming, her iPad and her swing. She hates cleaning her teeth, is indifferent to food other than milk and would like to rid the world of hair brushes."

When I received Sue's message, I did a Google search, and I couldn't find anything suitable either. So I gave Sue my phone number, she called me and I offered to write a blog myself. Sue has commissioned me to research and write this, and has paid me to do so. Thanks for trusting me, and for the challenge, Sue!

I'm using the terms "inspiration objectification" and "inspiration as objectification of people with disability". I've avoided the elephant in the room, while giving the amazing Stella Young a lot of credit and respect for the work she's done to initially raise this issue.

When I've previously mentioned inspiration as objectification of people with disability, using the term Stella Young coined, some people have felt uncomfortable. They don't like the term, so deny it exists or don't want to look into the issue further. This happened a lot during the #crippingthemighty discussions While I never want to censor myself, sometimes I realise the need to soften language to make serious issues more palatable, to reach an audience that needs to hear it. There is definitely a need for this post.

This post links to articles and videos about inspiration objectification that might require parental or teacher supervision. It also contains photos that are ableist, and links to websites I wouldn't usually link to. I do not endorse this type of content, it's here to exemplify. It's a long post, with lots of quotes from almost only people with disability - I wanted to make this as informed and balanced as possible. I hope it's useful.

What is inspiration objectification?

This illustration is a great first glance summary of inspiration as objectification of people with disability.

(Illustration of people cheering on a person in a wheelchair, holding patronising signs including "handicapable".

The heading is "Spectators". )

It's called "Spectator" and the image by Jessica and Lianna Oddi of The Disabled Life - used here with permission.

The late Stella Young, disability activist, writer, speaker and comedian, wrote and spoke about the problem with the objectification of disability though social media memes and mainstream media. In her 2014 Ted Talk, Stella said:

"I am not here to inspire you. I am here to tell you that we have been lied to about disability. Yeah, we've been sold the lie that disability is a Bad Thing, capital B, capital T. It's a bad thing, and to live with a disability makes you exceptional. It's not a bad thing, and it doesn't make you exceptional.

"And in the past few years, we've been able to propagate this lie even further via social media. You may have seen images like this one: "The only disability in life is a bad attitude." Or this one: "Your excuse is invalid." Indeed. Or this one: "Before you quit, try!" These are just a couple of examples, but there are a lot of these images out there. You know, you might have seen the one, the little girl with no hands drawing a picture with a pencil held in her mouth.You might have seen a child running on carbon fiber prosthetic legs".

She continued:

"...they objectify one group of people for the benefit of another group of people. So in this case, we're objectifying disabled peoplefor the benefit of nondisabled people. The purpose of these images is to inspire you, to motivate you, so that we can look at them and think, "Well, however bad my life is, it could be worse. I could be that person."

You can view her Ted Talk and read the transcript here.

Stella's talk had me (and many disabled and non-disabled people) thinking about inspiration objectification. Stella's famous term has even been cited in the American ABC series Speechless - it's so good to see this in pop culture.

Inspiration objectification is quite easy to spot when you know what it is. Here are some examples:

It shows a picture of disabled people living life and asks non disabled people what's their excuse?

(Photo collage of a boy in wheelchair holding a basketball, with the text 'Your excuse is invalid' on a black background. There are other kids behind him.)

It shows disabled people doing "normal things", suggesting seeing this will make non disabled people smile. I put normal in speech marks because the use of the word is othering.

It shows non-disabled people doing good deeds for disabled people - feeding them chips at McDonald's - "serving us all lessons in kindness": or taking them to the high school dance These stories usually always go viral. The person with disability probably never gave their permission for the photo or story to be used in a meme or told to the media.

It's stories of disabled people miraculously walking, overcoming their disability.

It's showing people with disability as heroes or "super disabled" - like this story of the body builder who is "hailed as an inspiration".

It's perpetually infantilising, showing non-disabled people giving disabled people the opportunity of a lifetime - like this video of a young man helping operate the checkout (also read how people are inspired by him in the comments).

It implies disabled people can inspire, just through existing.

(Photo featuring woman in a wheelchair, facing the sea. Text reads: 'never ignore someone with a disability, you don't realise how much they can inspire you. share if you agree'.)

It's merely associating the word inspiration with disability - like Inspiration Island, a park for people with disability.

It's taking pity on people with disability, though asking for prayers on social media posts. Stop that!

It also implies parents of children with disability are more heroic and better equipped than parents of children without - like this meme - I made it myself! (I'm thinking of the irony if it's shared!)

(Shareable graphic featturing a pink watercolour heart, with the text God only gives special needs children to special parents".)

Of course these social media posts and articles I've linked to are problematic. They are often also ableist - you can read about ableism here.

Inspiration as objectification of people with disability sets and perpetuates low expectations about us.

It portrays disabled people's lives as tragic. It also praises us for just living life - as Stella said, implies we are exceptional for doing every day things like working a long career at McDonalds.

It makes other people feel good (you can tell this from the comments threads on social media posts - but often those people are not interested in improving and maintaining disability rights!).

It often features non-disabled people, doing a good deed for the person with disability - and they're praised for their deed.

And if a disabled person makes their own media - like the woman with no arms who does makeup video tutorials - the media often frames this as "normal" or "extraordinary".

Now that I've given you some examples and described how they're problematic, I want you to think about what these social media posts and articles would be like if you replaced "disabled" or "disability" with the words "black" or "gay" or even "woman" or "man". Do you think reporting like this about people without disability would be acceptable? No.

The Indiana Governor's Council Governor for People with Disabilities is holding Disability Awareness Month in March. The 2017 Disability Awareness month campaign theme is "I'm Not Your Inspiration."

The council has created some great resources to make people think twice about circulating inspiration objectification images and articles, and help stop seeing disabled people as inspirational just for existing. You can download classroom and workplace posters from their library for free.

I am not your inspiration, I'm your classmate:

(Photo of a school boy with the text "I'm not your inspiration. I'm your classmate".

The photo is in black and white and there is orange detail on the poster.)

I am not your inspiration, I'm your co-worker:

(Photo of a woman in wheelchair. text reads "I'm not your inspiration, I am your co-worker.".

The photo is black and white, and the poster has pink and purple detail.)

These are so useful!

I realise this post, as an educative resource, is super long. Parents and teachers might just want to use the content until here, or continue reading to find out how inspiration objectification makes people with disability feel.

What if you're a subject of a Facebook post aimed to make people feel inspired by or pity for you?

Last year, my teenage friend Stella Barton was featured on a Facebook page featuring stories and photos of people in Melbourne. Her photo was not used, but the page creator wrote a story about her, after seeing Stella and her friend (also with a disability) at the train station. The post received a lot of heart-warmed comments, and even Stella's friend was ok with it. But Stella wasn't ok with it - she asked for it to be removed.

(Photo of Stella Barton and Carly Findlay.

They are both smiling and are dressed fabulously in green and pink.)

Stella told me how she felt about being heralded as an inspiration on Facebook.

"It was funny because [my friend] wasn't bothered by it but I thought it was strange that it was so exciting for the person who wrote the article that two disabled people were doing their own thing - supporting each other getting through crowds of people, and that was remarkable enough to write an article about us.

"As a visibly disabled person you get used to being stared at a lot in public but it's another thing for people to assume they know what's going on in your life and write s story about it.

"They actually made up the fact that I was crying and that just made me embarrassed. They also used my name in the story without my permission and so my Facebook friends immediately knew it was me which annoyed me.

"But this is all my opinion and if you asked [my friend] about it she wasn't bothered at all by it. We just have different views about it."

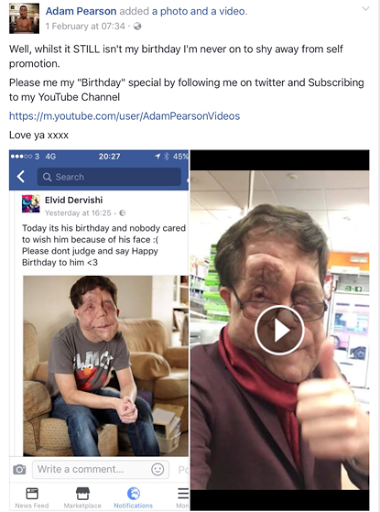

Last week, Adam Pearson found his photo stolen and misused on a clickbait Facebook page. The owner pitied him, calling for people to wish him a happy birthday. Hundreds of sheeple blindly followed instructions, wishing him a happy birthday. Adam is a self confident, articulate and successful TV star and producer. And it wasn't Adam's birthday.

Not one to shy away from self promotion, he took advantage of the opportunity to promote his own page and YouTube channel.

You can see the original post misusing Adam's photo on the left - saying no one wished him a happy birthday because of his facial disfiguremeant, and asking people to wish him happy today and not to judge. On the right is a video from Adam, which you can watch here. Adam's text, prefacing the screenshot and video reads:

"Well, whilst it STILL isn't my birthday I'm never on to shy away from self promotion.

Please me my "Birthday" special by following me on twitter and Subscribing to my YouTube Channel

Love ya xxxx"

How does seeing inspiration objectification in the mainstream and social media make disabled people feel?

I asked some activist friends how they feel when they see articles praising non-disabled people for hanging out with disabled people and photos with the phrase "the only disability in life is a bad attitude" (and similar).

Cara Liebowitz says:

"It makes me feel tired, honestly. Because I experience it SO MUCH. It has a negative effect on the way people see disability because it makes us seem like we're superhuman just for doing ordinary things, which stems from the stereotype that all disabled people do is sit at home and collect a check from the government. And some disabled people do that, because they can't work for whatever reason. But they still have friends, hobbies, they're still well rounded people. Inspiration [objectification] turns us into caricatures."

Kyle Khachadurian, who hosts The Accessible Stall Podcast with Emily Ladau, tells me:

"I just find it vacuous. It doesn't bother me, it doesn't offend me. I don't get up in arms about it. It's the most inane, pointless thing. It means nothing. All it does is make someone feel like they've done a good deed for the day somehow "on my behalf" because they said something to me and it's like, ok but now what? Are your perspectives actually changed because if not you actually did worse than if you'd done nothing at all."

"Inspiration [objectification] used to be a punch in the gut every time I’d encounter it, but it’s so commonplace that I’ve had to steel myself against it. It makes me feel like I am nothing more than someone else’s object, an oversimplified source of warm fuzzy feelings with no regard to the complexities of my humanity. Every time I see someone sharing inspiration [memes or articles] or am treated as someone’s inspiration, I struggle with the fear that calling them out won’t help them understand why it’s problematic, but rather will only serve to make them perceive me as bitter. And while I actually don’t think it’s unreasonable for me to be bitter about constant objectification for the sake of good feelings by most of society and the vast majority of mainstream media...bitterness is not the issue. I just want people to recognize that I am only human, and if you’re going to be inspired by me, I’d like it to be for reasons other than that I got out of bed and lived my life."

(Listen to Kyle and Emily's excellent discussion on inspiration.)

Alice Wong, who founded the Disability Visibility Project describes inspiration objectification as:

"like a media hangnail. It's annoying and difficult to avoid. [It] is omnipresent and insidious. I feel drained just reacting to the same stories/cliched headlines over and over. I try to be selective about which articles warrant a response from me via social media because it often leads to unproductive discussions or misunderstandings about why "feel good" stories can be so harmful.

"There's also the dynamic within the disability community of disabled people perpetuating inspiration [objectification] and embracing it. Each to their own, I guess. We're certainly not a monolith and I'll continue to express my disdain."

Bill Peace feels the type of social and mainstream media I've written about here to be dehumanising.

"[It] is based on antiquated notions about what life is like with a disability. The very idea is utterly dehumanizing. Typical life, it is assumed, is impossible. One is an inspiration or a failure. A person "overcomes" a given disability or is a failure. The failure is shamed by the "inspirational" hero. In individualising disability the social ramifications such as economic disparity, joblessness, educational barriers, social stigma etc. are conveniently dismissed as variables."

Karin Hitselberger has used social media to take control of her image, to empower her.

"Personally I'm a huge fan of selfies, and in a way, I kind of think of them as the "anti-inspiration", because what they do is they give the power back to the person being photographed. They let the subject of the story right the narrative and decide how they want to be seen. Instead of being stared at, or photographed out of context, selfies let you acknowledge that people are going to look, and that they see you as, "other", but they let you tell the story. They don't turn you into an object of pity, or a superhero, they let you be yourself on your own terms."

How does it feel to be called an inspiration because of our disability ?

While inspiration objectification happens a lot in mainstream media and social media, it happens in "real life" too. As I and many friends write here, it feels strange to be called an inspiration because of our disability - especially if it's merely for living. And maybe people calling us inspirations in this way is because of the memes and articles that seem to portray every disabled person as inspirational?

I get told I'm an inspiration quote often. Of course, it's one of the better bad words I've been called, but it bothers me because so often I'm just called an inspiration for existing, not for making a true difference in the world (which I do set out to do). I am not inspirational because I have a disability yet also manage to have a day job and a super busy freelancing career. I am not inspirational because I got married, even when so many made me feel I would never find love (and some told me too).

Sometimes when I write an article for a news website and it's shared on Facebook, a person will say "I see this lady on the train. She's such an inspiration." Wait what? I'm catching the train, usually to work, sometimes to dinner or to see a band or do some shopping. Just living life, not an inspiration. And their opinion of me is formed by seeing me catching the train, not engaging with me at all. They might see me ask for a seat if I'm sore, or scrolling through my phone - preparing my social media for the day, or see me get off the train for work. But they don't know me at all. I feel they have really low expectations of me and others with facial differences and disability if they are amazed to see me on the train. They could think my life must be so miserable that it's a wonder I can face the world, travel on a train and have a job.

I don't mind being called an inspiration if I've done a really good job at something - like written an article that has made people think, or performed well at Quippings or even run a far distance on the treadmill (ha!).

Friends with disability tell me they feel awkward too - and even dislike - being called an inspiration.

"If I'm doing something good that makes a positive difference in the world, then great. Just being and living the day the day isn't inspirational - it's just my life."

(I'm inspired by Camille's ability to sew a dress in two hours! That's a skill, she said!).

Vanessa tells me:

"Inspiration = A Saint (at least, in most people's eyes). And I am definitely not that!

I suspect I feel so strongly about this because I used to belong to a church group where people that just met me would call me, you guessed it, inspirational! And after getting to know me, and seeing some of my quirks and foibles, they realised that I was simply a human being like them.

The thing is though, some of them started treating me badly from that point on — as if they were angry with me for no longer "being an inspiration" to them!

I wish they could have realised that nothing about me actually changed. Only their perception. And I guess I wish they had realised that expecting me to be their inspiration was kind of placing an unfair amount of pressure on me. Like I was never allowed to be anything less than a saint!

I never asked or wanted to be anyone's inspiration."

Karin, who is the mother of Nico, a little boy who had a severe disability and passed away in 2014, wrote to me:

"I don't have a disability but my son did as you know. I was at a cafe on a family holiday. He was peg fed (and in a wheel chair) so I hooked up his feed and apart from that we just sat around like any other family, chatting and minding our own business. A lady came up and patted my shoulder and whispered to me "I just wanted to tell you, you're an inspiration". My first instinct was warm fuzzies. How lovely to get such kind words from a stranger. It took a few minutes for it to turn into feeling almost an insult. What was I doing that was so amazing it warranted such praise and acknowledgement? I was feeding my 4 year old. Loving my four year old. Giving my four year old a family holiday in a nice place. What was the alternative? What was this well-meaning lady's expectation of a "normal non-inspirational" parent? Did she expect my life to be miserable? Did she expect my holiday to be away from my child?

I know it came from a good place, I do. It's nicer than taking a wide berth and trying to avoid eye contact in case it gets perceived as staring. I was trying to think of a more fitting piece of encouragement and I think "you're doing a good job" or "you're a great Mum" wouldn't have given me that feeling because I would have accepted and appreciated that if I had have been having a regular day out with my daughter."

Bettina says:

"I mind. I mind a lot. I'm just over here living my life, adjusting what I want to do within my limitations - doesn't everyone do that? Chronic pain/illness/disability or not? Why is it more remarkable for me to carry on doing ordinary everyday things despite high pain levels? Was I meant to have faded into a corner somewhere to sob quietly and give up on living? I don't know. It makes me wonder about people's expectations of what it's like to live with chronic conditions and frankly makes me not want to open up to many about mine."

Is it ever ok to call a disabled person 'inspirational'? Some people think so.

Like me, some of my friends don't mind it if they're called inspirational because they're doing something great. Something that's more than just existing. Sometimes it's because of their disability. They might want to be a role model or show people they can manage day to day, even though their disability is a hard slog. They want to show they can overcome. Sometimes why they're recognised as being inspirational by other people is partly to do with their disability - like running a support group, or being really good at wheelchair sport.

"My disability is a chronic, 'invisible' illness, which society usually underestimates or mistakes for laziness. Instead of pity from strangers, I'm more likely to evoke irritation when I don't walk fast enough on the footpath. When my close friends, who know what I go through, tell me I inspire them, it means a lot to me. By the current government's standards, I am failing at life because I don't have a "good job that pays good money". Taking care of myself is not seen as a full-time job (it is), and the constant obstacles to living well with my illness are disregarded. I don't set out to inspire anyone. But it helps to hear sometimes, by people who know me (and aren't strangers throwing me a pity parade) that I am worth looking up to."

"I have some issues with being called being 'inspirational' for everyday stuff like going to work or catching the bus. However I don't mind if it relates to my going from being a very unwell and disempowered prisoner and homeless person to an internationally published author, TEDx speaker and ACT Volunteer of the Year 2016 -I mean that sort of IS inspiring. It also depends on the context, If a friend or colleague says it and I know it's genuine that is fine but when it is used by people who don't really know me as a sort of throwaway statement and they probably say that about every person with disability they meet, that irritates me."

"If someone finds my sporting achievement inspiring for example, that's a different kettle of fish. I've had to overcome more barriers than most people to even gain access to sport because of my disability and I'm constantly pushing to achieve more. I can see how people might relate to that adversity and how it might motivate them to tackle their own challanges and to achieve."

"I have found it pretty outrageous the few times I've been told I'm an inspiration because of my disabilities, but it was the context that was outrageous, as in, 'because I exist, I'm an inspiration!'.

"I think taking accomplishments and adding disability to the picture makes the combined package of 'inspiration' digestible for me. I am not an inspiration just because I'm deaf and have traumatic brain injury (TBI) and bi-polar disorder; but the fact that I speak proficient Japanese as a deaf woman, and the fact that I am so highly organized, live in a challenging physical environment and am consistently hard-working and energetic, while living with bi-polar and TBI is something."

"I don't mind horribly when people call me inspirational or admire me for doing what I do - sometimes it's bloody hard work to live like a normal person, and I appreciate the recognition. If they get super gushy I will feel uncomfortable, but mostly if I start to feel it's at all unwarranted/unwanted I'll try to politely redirect the conversation to the things I actually feel proud of. People mostly mean well, and I try to acknowledge that.

"I think when we have to overcome major obstacles, especially if it's been necessary to create new techniques or something like that, it's good to be seen as inspirational. We've done hard work, we've created something. If it's just 'being in public like a normal person' that's obnoxious, but if there's real obstacles to be overcome like physical impediments that I or others have found a way (personally) around or hacked something that existed to work for us, that's worthy of recognition. A lot of the things that we take for granted as possible for PWD now are only possible because of those kinds of actions by people who are worthy of the term inspirational."

"I feel I am in a unique position. I have suffered over 560 fractures in my life. Despite that I have been successful in an industry that is competitive and driven on looks. For those reasons I feel I am inspiring", he tells me.

"Not for simply been alive. I don't think being disabled is enough to be inspirational anymore. I feel that to be inspiring you have to have achieved something other than what society deemed possible.

"Let's take your disability. Do I think it's inspiring that you have it? No not really. What makes you inspiring that even though you have suffered ridicule and persecution from others and you still choose to stand proud and advocate for yourself and others. That I find inspiring"

Elise implies that she can teach people inadvertently:

"I don't mind [being called inspirational]. It happens a lot. If I can help people not to whine about having a zit, great - I am all for it! As long as their tone is not condescending."

And while Sonia doesn't like being someone's inspiration just for doing every day things, she can understand why she might inspire people.

"I've never found my disability inspiring because it's not something I planned to have happen to me. I have problems with people thinking I'm an inspiration when I do things that 'normal' people do because if I wasn't disabled then I wouldn't be called inspiring for doing those things. BUT I know that the people who would call me inspiring are saying it because, to them, I really am inspiring because I realise that they can't know or imagine trying to do the 'normal' everyday things with disability.

"I don't set out to inspire people but if I can change peoples reactions and outlooks towards those with disabilities then great and if that is inspiring then others can feel free to think that", she continues.

"It can be seen as belittling but, in all honesty, if a person wants to belittle you then they can call you worse things than inspirational."

Some disabled people even feel there are bigger issues to worry about than media showing disability as inspiring.

Ryan Haack, who is a writer and speaker with a limb difference, believes that disabled people speaking out about inspiration objectification in the media is problematic. With reference to last years Super Bowl ads, which were deemed as inspiration, Ryan wrote

"The fact is, differently-abled people aren’t represented very well in mainstream media. Some activists decry this injustice quite often. But then ads like these come out and those same people complain about them being “inspiration p***.” Frankly, it’s not a good look for our community. "

He continues:

"As someone with a limb-difference, there are a lot of things I could get angry about.

Inspiring others – even if I think that inspiration is, perhaps, silly – is not one of them."

While I agree with Ryan that there are big issues for people with disability, representation us in media and advertising really does matter.

"The word "inspiration" has been so misappropriated by non-disabled people that it's lost all meaning.

"You do your own shopping without help? You're such an inspiration."

Inspired you to do what, exactly? Go out and buy a pint of milk? Don't you need to do that on a regular basis anyway?

I pity non-disabled people and their ignorance which leads to a misunderstanding of language.

It is never OK to view someone as an inspiration purely because they're disabled. It can be OK to be inspired by disabled people when they've done something amazing like won a Paralympic gold medal; you can be inspired to get a bit fitter or pursue something else that's difficult but floats your boat. As long as you don't think/say "well if a disabled person can swim fast, I've got no excuse," because that's just a prejudiced presumption of incompetence.

In short; it's only OK to be inspired by a disabled person if you'd be inspired by a non-disabled person doing exactly the same thing. Would you be inspired by a non-disabled person putting on their own pants? No? So how is it inspirational when disabled people do that?"

It's complex, hey? There is no one answer, but I guess we all need to do our best not to perpetuate the low expectations of people with disability by creating and sharing content objectifies people with disability by implying we are inspirational just for living. And I hope the perspectives I've shared here make you understand the impact that inspiration as objectification of people with disability can have - both on disabled people and non-disabled peoples's perceptions of us.

Further reading (As mentioned, these links may require parental and teacher supervision.):

Is there something you would like me to write? You too can commission me to write a blog post too - contact me for my rates. If this post has helped you, or you're using it in your classroom or as a parent, please consider buying me a drink.