An Introduction to Tube Feeding the Critical Patient Critically ill patients benefit [�] The post Tube Feeding appeared first on Hill's Veterinary Nutrition Blog.

An Introduction to Tube Feeding the Critical Patient

Critically ill patients benefit from provision of early nutritional support in the hospital setting. It is recommended that patients receive nutritional support generally within the first 24 hrs of hospitalisation- especially since many patients have reduced caloric intake for several days prior to admission to the clinic or hospital.

In general, enteral nutrition is far superior to intravenous nutrition. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) results in reduced liver function in comparison to patients fed enteral nutrition. In addition, the sepsis rate is 2-3 times higher in critical patients and the rate of infection in trauma patients is 2-3 times higher in patients fed with TPN, when compared to those fed by the enteral route.

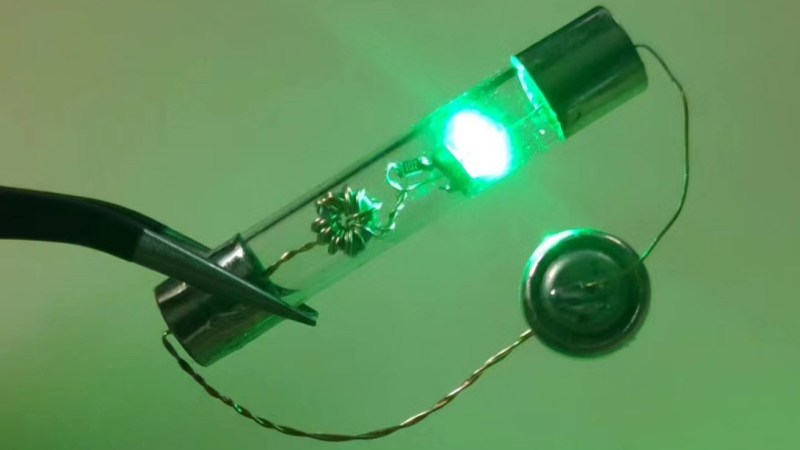

Routes and methods of tube feeding

Repeated orogastric intubation (including syringe feeding and force feeding)

May cause significant stress to the patient Orogastric intubation provides an increased chance of incorrect tube placement, oesophageal trauma, vomiting and aspiration pneumonia Not recommendedNasogastric/Naso-oesophageal tube feeding

Easy to place and well tolerated Small tube diameter means that these tubes are only useful for feeding liquid diet formulations e.g. Emer-aid If the tube is placed in the stomach, a reflux oesophagitis may result Complications of tube placement include aspiration pneumonia, vomiting, tube migration, oesophageal irritation, inflammation and scarring, tube clogging (due to small tube diameter), and epistaxisOesophagostomy tube feeding

Gastrotomy tubes

Require a general anesthetic to place. Tube may be placed via endoscope, percutaneously or via laparotomy Must leave in for at least 7-10 days minimum prior to removal to allow a fibrous seal to form between the stomach and abdominal wall Complications of tube placement include vomiting, tube migration, tube clogging, peri-stoma infections, splenic laceration (percutaneous placement), pneumo-peritoneum, and gastric haemorrhageJejunostomy tubes

Bypasses the upper portion of the gastrointestinal tract. They may be useful in animals with conditions affecting the stomach and upper small intestine, such as neoplasia, major surgery, and in patients with persistent regurgitation These tubes require abdominal surgery (laparotomy) to place Small diameter tubes (similar size to nasogastric tubes) mean liquid-only diets can be fed Small frequent or continuous feeding required to prevent intestinal distension around the tube, and patient discomfort Complications include tube migration, tube clogging, peri-stoma infections, and diarrhea and vomiting from inappropriate feeding techniques, hyperglycemia and electrolyte disturbances, and hypoglycemia (if feeding abruptly stopped). Very occasionally, the tip of the tube can perforate the small intestine, and result in leakage of intestinal fluid into the abdominal cavity, causing severe peritonitisWhen to begin tube feeding

Enteral nutritional support should commence within the first 12 hours of patient hospitalisation if possible, to avoid negative consequences of protein-calorie malnutrition.

Nutritional support is greatly facilitated by feeding tube placement and should begin in earnest shortly following placement. Patients with nasogastric/naso-oesophageal tube, and oesophagostomy tubes can be fed soon after tube placement � whereas gastrostomy and jejunostomy tubes require a period of 24 hours before nutritional support can commence.

A brief outline of feeding introduction is presented below:

Step 1: Micro-Enteral Nutrition

Micro-enteral nutrition is the delivery of small amounts of water, electrolytes, and readily absorbed nutrients (glucose, glycine, glutamine, amino acids and small peptides) directly to the gastrointestinal tract, prior to the onset of complex nutritional support. Micro-enteral nutrition improves blood flow to the gut, improves gut function, and improves tolerance to more complex diets when subsequently fed.

Administer as a slow bolus of 0.5-2 ml/kg via feeding tube every 1-2 hours and should continue throughout the period of critical care hospitalisation.

Step 2: Beyond Micro-Enteral Nutrition

If the patient tolerates micro-enteral nutrition, more complex diets should be fed via feeding tube. These can be fed generally 6-12 hours following commencement of micro-enteral nutrition. The exact choice of diet is somewhat influenced by the underlying disease.

A critical care or nutritional recovery diet formulated for the species being fed is recommended for many patients, as these diets have high caloric density, and have sufficient protein and fat content for recovery, and have less carbohydrate content when compared to diets formulated for humans, which minimises risk of hyperglycaemia � which has a negative effect on recovery for many critically ill patients.

Step 3: Feeding the Patient

As stated above, enteral feeding should ideally be initiated within 12-24hrs of admission to the hospital. Small bolus feeding is recommended in the clear majority of patients, over continuous infusions (except when feeding via jejunostomy tubes), as bolus feeding is more physiological, and provides time between feedings for bowel rest. For patients with persistent vomiting or regurgitation, residual gastric volume can also be monitored, and the feeding regime adjusted as outlined below.

In all cases, the target energy and protein requirements for the patient should be aimed to be met by the third day of feeding. However, it should be noted that this may not be possible in all patients, and it should be recognised that some nutritional support is better than none at all, even if complete RER calories cannot be fed for some days, due to dietary intolerance or underlying gut dysfunction.

How much to feed

Bolus Feeding Protocol for Gastrotomy, Esophagostomy, or Nasogastric Tubes

| Day 1 | Feed 1/4 � 1/3 of daily nutritional requirement in several small feeds |

| Day 2 | Feed 1/2 � 2/3 of daily nutritional requirements in several small feeds |

| Day 3 | Feed entire nutritional requirements in several small feeds |

To learn about Hill�s a/d diet that encourages eating for pets recovering from surgery, illness or injury click here.

If feeding via gastrostomy tube, or nasogastric tube, suction the tube first � if a volume greater than 1/3 of the previous volume of feed given is suctioned, delay the next feed for 2-3 hours, and feed 1/3 � 1/2 the volume of the last feed. Consider the presence of intestinal ileus, and manage with metoclopramide and/or cisapride pro-motility medications.

Feeding tube care

The feeding tube stoma site should be inspected every 6-8 hours, in patients with oesophagostomy, gastrostomy or jejunostomy tubes, and cleaned with sterile saline and 0.1% iodine solution, followed by application of iodine ointment, and a sterile bandage. Samples should be collected for antimicrobial culture should the wound begin to suppurate, or if it becomes red, swollen or hot.

Conclusion

Nearly every major study conducted in human and veterinary literature supports the importance of beginning early nutritional support in hospitalized patients, regardless of their illness. The most important things to remember about nutritional support are firstly, to begin nutritional support early, using micro-enteral nutrition, and to follow this up with the feeding of a diet that is appropriate to the animals� condition, beginning with small volumes, increasing to meet the animal�s dietary requirements within 3-5 days of hospitalization. Failure to attempt to do these things results in poorer outcomes for the patient. In addition, pharmacological and fluid support of the gut will improve tolerance to feeding and will improve patient comfort.

To learn more, read Hill�s Blog on developing a nutritional plan for critically ill patients or, to work out critical care feeding calculations, visit Hill�s Veterinary Academy and watch a short 7-minute video here.

Dr Philip Judge� BVSc MVS PG Cert Vet Stud MACVSc (Vet. Emergency and Critical Care; Medicine of Dogs)

Philip graduated from Massey University in New Zealand in 1992, and after several years in small animal private practice, completed a residency in veterinary emergency and critical care at the University of Melbourne, during which time he gained a Master�s degree in small animal emergency and critical care, and membership by examination to the Australian College of Veterinary Scientists in the same subject, as well as Medicine of Dogs.

Philip is currently Adjunct Senior Lecturer in Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care at James Cook University. He is co-founder and chief tutor at Vet Education � a leading global provider of online education for the veterinary profession. He is a published author in scientific literature, and has spoken at numerous veterinary conferences around the world � as well as online. Philip�s chief clinical interests include snake envenomation, ventilation therapy and the management of sepsis.

The post Tube Feeding appeared first on Hill's Veterinary Nutrition Blog.