On the 27th of July 2018, an experienced pilot departed with ten parachutists on board for a routine drop mission. It was the pilot’s fourth flight of the day in the Pilatus PC-6 Porter, a single-engine aircraft popular with...

On the 27th of July 2018, an experienced pilot departed with ten parachutists on board for a routine drop mission. It was the pilot’s fourth flight of the day in the Pilatus PC-6 Porter, a single-engine aircraft popular with parachuting and skydiving operations for its short take-off and landing capabilities and low maintenance requirements. The flights were operated by the École de parachutisme de Midi-Pyrénées (Midi-Pyrénées Parachuting School) at Aérodrome de Bouloc in Southern France.

The pilot of the accident flight was the chief pilot of the parachuting school and held a commercial pilot license, a class instructor rating and a Pilatus PC-6 rating. He had a total of 13,366 flight hours, including 7,560 hours on the PC-6. His Class 1 medical certificate mandated a second qualified pilot for all commercial flights but he later said that he believed that he was legal to fly solo.

The weather was clear and warm that day, with a wind of 5 knots on the ground and 15 knots at 4,000 metres, the final drop altitude. The deputy technical director of the parachuting school gave a field briefing to the parachutists. The briefing was focused on the parachute landing options, including alternate landing areas (in case the jumpers could not reach the aerodrome) and the precautions necessary if they found themselves near power lines. It did not include the manoeuvre zones or the aircraft descent zones.

The pilot did not give any further briefing to the parachuters.

Two of the parachutists wore wingsuits, a type of jumpsuit with webbing between the arms and the thighs to act as an airfoil. The increased lift allows the wearer to glide before deploying the parachute to slow the descent for landing.

This two-minute video shows a straight jump from a rocky outcrop through a cliff (if you are reading this in email, you may need to click through to view the video).

The top two comments are:

Lets you appreciate the huge tasks birds do just to say alive.

and

I get the feeling there are no small mistakes in this sport.

Aircraft jumps are considered to be much less dangerous.

The BEA accident report from the jump at Bouloc refers to Paralog Performance data for precise data for the wingsuits worn by these two flyers.

As soon as they exit the aircraft, wingsuiters convert part of their vertical speed into horizontal speed. This phase lasts about fifteen seconds, during which the wingsuiter’s lift-to-drag ratio increases from about 0.5 to 2.5. The lift-to-drag ratio then stabilizes between 2 and 2.5.

The first parachutist was to jump at 1,500 metres (~5,000 feet) and then the other nine at 4,000 metres (~13,000 feet). The two wingsuit flyers would be dropped last.

The flight departed from runway 28 at 10:00. Although the report doesn’t mention it, the first parachutist presumably jumped normally at 1,500 meters. The PC-6 continued to climb to 4,000 metres, where the next seven parachutists jumped from the plane at six second intervals.

The French Parachuting Federation specifies that when a wingsuit flyer exits the aircraft, he or she should then continue in a path parallel to the aircraft for twenty seconds. There’s no procedure for the pilot, although the pilot would generally initiate a slight descent and negative attitude to keep the horizontal stabiliser as far from the parachutists as possible. Investigators found that after a drop, the PC-6 generally descended at a vertical speed between 3,500 and 5,500 feet per minute, making for a slope of 20-30°. The wingsuit flyer’s slope would be at 10° after the jump and into the glide parallel to the aircraft. After 15 seconds of descent the slope increases to 35° and then drops to 20° in stabilised flight.

That day, the pilot slowed the PC-6 to 65 knots. The first wingsuit flyer exited the aircraft and continued on a path parallel to the aircraft. A few seconds later, the second wingsuit flyer followed. The wingsuit flyers disappeared out of his view, which was normal. The pilot started his descent back to the airfield. He didn’t have visibility of the flyers but entered a left turn to avoid flying into their path.

The second wingsuit flyer had a camera mounted to his helmet. The camera filmed the first wingsuit flyer in front of him. Suddenly, the PC-6 appeared a few metres in front of him.

The aircraft shook with a violent impact. The aircraft’s left wing had clipped and killed the wingsuit flyer in front. The wingsuit flyer’s parachute deployed and the body drifted down to a field.

The pilot was immediately aware that he must have collided with one of the flyers. The left flap was damaged, but the PC-6 was otherwise flyable and the pilot returned to the aerodrome. The pilot believed that he had descended normally and that the wingsuit flyer must have been off-course.

Investigators used the video from the second wingsuit flyer and the aircraft’s navigation system data to recreate the seconds before impact.

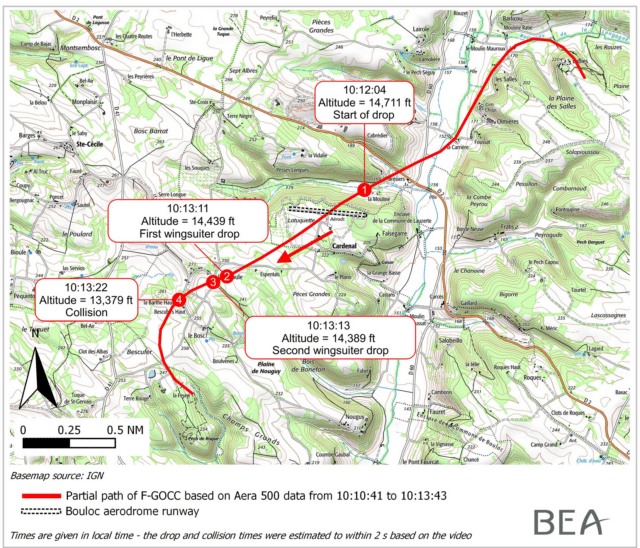

Partial path of the PC-6 with the wingsuit flyer drops and collision marked

Partial path of the PC-6 with the wingsuit flyer drops and collision marked

The first wingsuit flyer jumped at 4,400 metres, specifically 14,439 feet, and then glided parallel to the aircraft. The pilot said that his vertical descent speed was normal for a descent after a drop, estimating it as between 3,500 and 4,500 feet per minute. However, the data showed that this was not the case. The PC-6 started to descend even as the second wingsuit flyer jumped, flying a downward slope of about 50°, instead of the expected 20-30°. The PC-6’s average vertical speed was 5,800 feet per minute which increased to an average of 6,700 feet per minute from the time that the second wingsuit flyer had exited the aircraft until the collision. The wingsuit flyers could not see the aircraft, which was (or should have been) above and behind them. It would be difficult at best for the pilot to see the wingsuit flyers.

The first wingsuit flyer had been in the air for eleven seconds, still following the path parallel to the PC-6, when they collided at 13,400 feet.

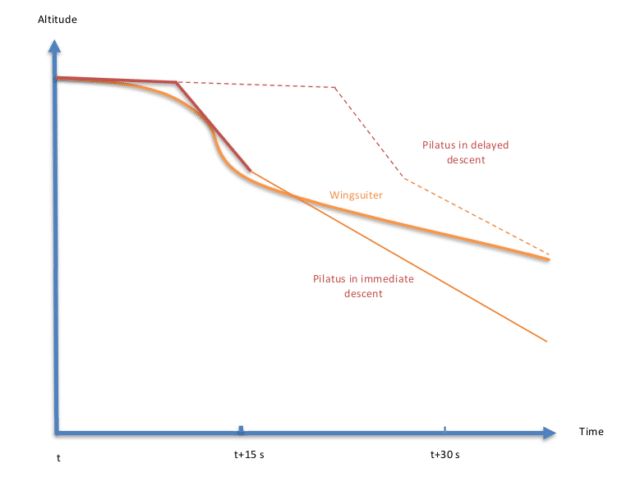

The following graph shows the expected descent of the Pilatus PC-6 and the immediate descent that led to the collision with the wingsuit flyer.

From the report: Usual theoretical vertical descent profile for a Pilatus and a wingsuiter

From the report: Usual theoretical vertical descent profile for a Pilatus and a wingsuiter

There is no specific procedure for a post-drop descent. The French Parachuting Federation 2016 safety report regarding mid-air collision focuses on the risk of another aircraft after the parachute is extended. The issue of a wingsuit flyer and aircraft colliding during the first seconds of the jump does not appear to have come up as an issue previously. Wikipedia has a List of fatalities due to wingsuit flying; almost all of them were BASE jumps (from high ground, for example cliffs, bridges or towers) and involved crashing into terrain. In fact, the linked article specifically clarifies that “aircraft descending a much less-deadly form of wingsuit flying.”

The final report was released in 2020 and cites the following contributing factors:

lack of an onboard briefing between the parachutists, the wingsuiters andthe pilot;? ?

the French Parachuting Federation (FFP) not identifying the risk presented by the

coexistence of aircraft and wingsuiter paths immediately after exiting the aircraft;

the immediate descent of the Pilatus, on a steep slope, commanded by the pilot even though he did not have visual contact with the wingsuiter(s).

Two years after this report, the mayor of Chamonix (in the French Alps) banned wingsuit flying for six months, after eight deaths in Franch that year, of which five were in Chamonix.

His view was that the sport was not regulated enough and the flyers did lacked experience for the flights they were attempting. If you are interested in more detail, Matt Higgens wrote a very good article about the ban and the dangers of wingsuit flying in Outsider Online last year: The Most Dangerous Part About Wingsuiting Might Be the Wingsuit.

You can read the final report on the BEA site.

As a result of this tragic crash, the French Parachuting Federation published an information bulletin about the need to define and separate the aircraft’s route from the wingsuit fliers, followed by a technical directive.

Pilot briefings for jump flights are now mandatory. The parachuting school has changed their procedures after the drop, asking pilots to adjust their power and maintain level flight for 10-20 seconds to ensure vertical and horizontal separation.

Last month, LeParisien reported that the pilot was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter and breaking the conditions of his medical certificate by flying alone. He was given a 12-month suspended prison sentence and banned from flying for one year. The parachuting school was fined €20,000 for not having confirmed the state of his license and medical certificate.