On the 4th of October 2023, an Airbus A321neo located in London Stansted was prepared for a multi-day charter flight in the US. There were three pilots and six cabin crew on board, as well as an engineer and...

On the 4th of October 2023, an Airbus A321neo located in London Stansted was prepared for a multi-day charter flight in the US. There were three pilots and six cabin crew on board, as well as an engineer and a loadmaster. This first flight was repositioning the aircraft and crew from London to Orlando International Airport in Florida. There were only nine passengers on board, employees of the tour operator and the airline operator.

The three-year-old Airbus A321-253NX was registered in the UK as G-OATW. With so few passengers (depending on configuration, the A321 typically carries from 180 to 220 passengers), the cabin crew boarded the passengers and had them sit in the middle of the aircraft, sitting in the rows before the overwing exits. The additional pilot and the engineer sat in the jumpseats on the flight deck. The loadmaster is responsible for cargo loading and transport in the aircraft. He sat in the cabin, in the row before the passengers.

The Airbus A321 taxied to runway 22 and departed at 11:15UTC, a few minutes ahead of schedule. Everything seemed normal on the flight deck; however, in the cabin, the passengers thought the aircraft seemed a bit noisy and colder than usual.

They climbed away from London Stansted for the 7,000-kilometre flight. As they passed through FL100 (10,000 feet), the flight crew turned off the seatbelt sign.

Curious about the noise, the loadmaster got up and walked towards the back of the aircraft. As he passed the passengers, he found a window seal flapping violently around a slipping window pane on the left side. The aircraft windows were made of stretched acrylic, and the window assemblies consisted of a seal, an outer pane and an inner pane (with a small vent hole so that the space between the two panes was at cabin pressure). The loadmaster couldn’t tell if it was the inner pane or the outer pane which had slipped. He quickly took a photograph and then told the cabin crew what he’d seen as he rushed to the flight deck.

Photograph taken by the loadmaster

Photograph taken by the loadmaster

By now, the Airbus A321 was climbing through FL130, showing on the FDR as 14,504 feet at 1013 millibars. They levelled off and reduced airspeed before checking the cabin pressure. The pressurisation system was operating normally; the cabin altitude was just over 1,500 feet. The engineer and the third pilot went to the cabin to inspect the window. The flight crew quickly agreed with them that they needed to turn back to Stansted.

The cabin crew asked the passengers to remain seated with their seatbelts fastened and gave them an additional briefing on how to use the oxygen masks if they should drop down from the ceiling. The aircraft descended to FL90 and flew a holding pattern northwest of the airport while the flight crew ran through the overweight landing checklist, confirmed the landing performance and completed the briefing for the return to Stansted.

They landed safely at 11:51 UTC, making for a total flight time of 36 minutes. Although they didn’t know it, as they taxied to the apron, an outer window pane shattered on the taxiway.

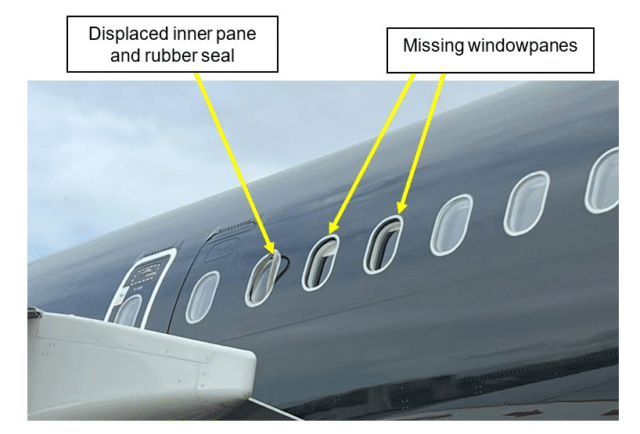

Once the passengers were safely out of the way and the aircraft parked and shut down, they carried out a visual inspection. Two of the cabin windowpanes were missing. Another window had a dislodged pane and a fourth window was protruding from the fuselage. Meanwhile, a runway inspection discovered the pieces of the shattered outer pane on the rapid-exit taxiway.

Displaced and missing windowpanes

Displaced and missing windowpanes

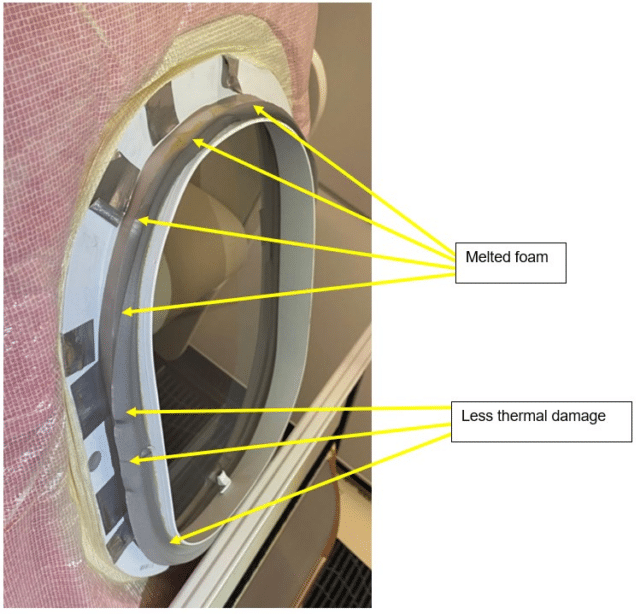

Inside the cabin, they removed panels of the cabin lining on the left side of the aircraft near the overwing exits to look for damage. They found that the foam ring material that surrounded the windows had melted in the areas around the damaged windows. The window panes were deformed and no longer fit into the rubber seals.

Foam rings around the windows

Foam rings around the windows

There was also a puncture on the underside of the left horizontal stabiliser. The stabilisers are at the back of the plane, parallel to the wings, and are used to control the pitch and attitude of the aircraft. When investigators removed the panel, they found small pieces of acrylic inside the stabiliser.

In a statement on their website, which has since been removed, the operator wrote:

The pilot did not declare an emergency and landed the aircraft safely, according to normal operating procedures. Emergency services at the airport were not activated.

(I’m not sure I like the implication that the situation was less serious because the captain didn’t declare an emergency.)

The day before the charter flight, the Airbus had been used for filming. Six sets of floodlights surrounded the aircraft which were identified by the film crew as Maxibrute 12. These flood lights have a lighting capacity of 12,000 watts with a maximum surface temperature of 200°C (392°F). The datasheet warns to keep them at least ten metres (33 feet) from the object to be illuminated. The spotlights had been set up to shine through the cabin windows to mimic a sunrise. The floodlights on the aircraft’s right side were directed at the cabin windows just aft of the overwing exits for about five and a half areas. On the left side, the floodlights were positioned similarly and focused on the windows for about four hours.

Once the British Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) were on site, the maintenance team removed panels of the interior cabin lining on the right side of the aircraft. They found again that near the overwing emergency exit, the foam material had melted, and the windows were deformed, although there was not as much damage as on the left side.

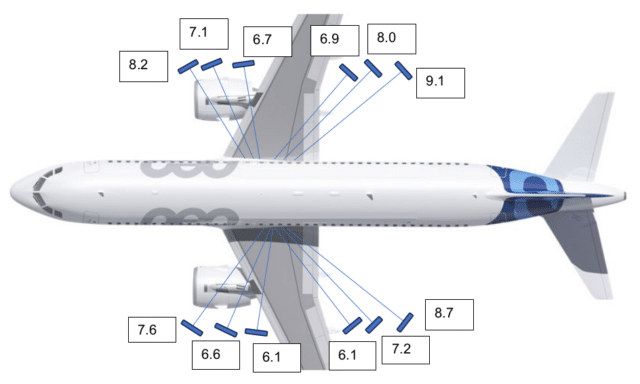

The AAIB inspected photographs taken during the filming activity the previous day. Using the photographs, investigators were able to reconstruct the layout and prove that the floodlights had not been kept ten metres away from the aircraft, but were positioned between six and nine metres from the damaged window areas.

Approximate distance in metres of the flood lights from the fuselage during the filming activity (image not to scale)

Approximate distance in metres of the flood lights from the fuselage during the filming activity (image not to scale)

The high temperatures had damaged and distorted the windows over the four to five hours of filming the previous day. Once the aircraft was in the air, the worst-affected windowpanes became dislodged and unsafe.

Flightradar24 points out that this is not the first time film lighting has damaged an aircraft window. In 2019, a window melted in a brand new Boeing 787-9 under the force of a spotlight used for a promotional video. At the time, this was blamed on the electrochromatic film that the 787 has between the inner and outer window panes, which allows the window to be darkened without shades. However, it’s becoming clear that modern studio lights need to be handled with more care when used to light up aircraft.

The AAIB released a special bulletin, to raise awareness of the circumstances around this latest case. The investigation is continuing with support from the French BEA and Airbus, in hopes of better understanding the issues and risks for using studio lighting around aircraft for future reference.

Luckily, the windows and their settings were damaged such that it quickly became apparent during take off. If the aircraft had reached cruising altitude for the transatlantic flight before the windows began to fail, the damage and the result could have been much, much worse.