You may remember this 2010 incident from Aviation Herald’s great reporting which led to international attention to the case. I wrote about Aviation Herald’s work on this in: 83ft above the sea at night and no investigation?. Initially, the...

You may remember this 2010 incident from Aviation Herald’s great reporting which led to international attention to the case. I wrote about Aviation Herald’s work on this in: 83ft above the sea at night and no investigation?. Initially, the Norwegian authorities dismissed the idea that the incident required official attention. Only after significant pressure from Aviation Herald did the Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) conduct a full review of the event and release a report of their findings.

The Aviation Herald has documented this very thoroughly, including the fact that the preliminary report was not quite the same in English as it is in the original Norwegian.If you are interested in more information about the investigation and the reports, I highly recommend reading Aviation Herald’s coverage, especially Aviation Herald’s exchange with the AIBN on their final report: Incident: Wideroe DH8A at Svolvaer on Dec 2nd 2010, aircraft rapidly descended on base turn, recovered at 25 meters AGL.

This is a long post so I have made an audio version for you! This audio recording is 30 minutes long. I recorded myself reading it aloud in my living room this afternoon so hopefully it isn’t too unprofessional! I’d love to hear your thoughts on whether an audio version is useful on long posts.

https://fearoflanding.com/files/2023/11/Unravellingthe2010incident.mp3What I want to do here is to focus on the Cockpit Resource Management (CRM) aspects of this case, where the two pilots have very different perspectives on what happened that night and what level of response was necessary. Specifically, the captain felt (and still feels) that the first officer had overreacted, increasing power for a steep climb after the situation was already under control. The first officer felt (and still feels) that the captain was not responding to the situation, and an abrupt intervention was necessary to keep the aircraft from crashing into the sea.

The Accident Investigation Board Norway published their final report in November 2016. This was six years after the actual incident, which took place in December 2010. The report starts with the AIBN explaining why so much time had passed between the incident and the investigation.

The Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) was only made aware of the incident in December 2012, two years after it had taken place. AIBN assessed the existing information, and collected further information. After an evaluation, AIBN concluded in June 2013 that the occurrence was to be considered an aviation incident. An investigation was not opened.

In February 2015, the incident was subject to significant attention, and AIBN found that the incident could contain a greater learning potential than first assumed. The decision not to investigate was changed. AIBN initiated an investigation in mid-March 2015. Following initial investigations, the Accident Investigation Board reclassified the case as a serious aviation incident.

The “significant attention” is, of course, a reference to the Aviation Herald piece outlining the incident and questioning why it had not been deemed worthy of an investigation.

For the sake of our analysis, the important point is that the flight crew were interviewed five years after the event and expected to recall the details of an incident that lasted just over ten seconds. However, the notes from the initial assessment were available to the investigation, including the FDR data and the detailed weather reports, without which this investigation could not have taken place.

The passenger flight departed Bodø on the 2nd of December 2010. The operator was Widerøe’s Flyveselskap AS, Norway’s oldest airline and according to their website, the largest regional airline in the Nordic area with a fleet of 40 Bombardier Dash 8 aircraft and three Embraer E-jets. The airline’s main base is in Bodø.

Both flight crew had earlier flights that day. The captain had a 40-minute flight to Narvik and then back. He rested in the lounge for an hour when he arrived back at Bodø. The first officer, who had been on stand-by, was called out for a 25-minute flight from Bodø to Svolvær and back again. He arrived back at Bodø just as the captain finished his break. They conducted a pre-flight briefing together, including an assessment of the weather.

Svolvær airport was showing wind at 30 knots gusting up to 44 knots, with rain and hail showers and cumulonimbus clouds in the area, which can represent thunderstorms. Visibility was 8 kilometres.

The forecast looked like the wind and the turbulence might be improving, so the crew decided they would fly to Svolvær and see how the weather was on arrival.

The aircraft that night was a Bombardier DHC-8-103 registered in Norway as LN-WIU. In addition to the two flight crew, there was one cabin crew and 35 passengers onboard. The captain was the Pilot Flying and the first officer was the Pilot Monitoring.

Their destination, Svolvær airport, is designated Class C, the most demanding category of airport with special requirements for operators wishing to fly in and out. Svolvær is surrounded by mountainous terrain. The runway is oriented north to south (01/190) and only runway 01 had an instrument approach. At the time (and possibly still), runway 19 was 776 metres (2,545 feet), with an upward slope of 1.5% just past the centre.

Svolvær seen from the northwest (runway 19) with red obstruction lights north of the airport. Photo courtesy of Avinor

Svolvær seen from the northwest (runway 19) with red obstruction lights north of the airport. Photo courtesy of Avinor

The AIP Norway lists the following warning for Svolvær:

Wind shear/vortexes can occur in the last part of the final approach to RWY 19 at wind sector SW-NW greater than 25 KT.

Inbound pilots often circle at Svolvær, coming around the other side to land to the south. Widerøe, the operator, say that this happens more often than the wind conditions warrant. The investigation confirmed this, concluding that even when there is no wind, pilots still preferred to circle to the south, since the upward slope of the runway gave them the shortest stopping distance.

Widerøe’s airport briefing lists a number of risk factors associated with Svolvær Airport, including weather, turbulence, mountain terrain, special procedures for missed approach and the risk of a “black hole effect”.

The black hole effect, sometimes called the “featureless terrain illusion” is a known optical illusion that takes hold of pilots during night visual approaches where the runway is in sight but no other ground lights can be seen between the aircraft and the runway. The pilot or pilots become convinced that they are higher than they are and fly a much lower approach than is necessary.

The sun had already set when the Dash-8 flew the approach to runway 19. The skies were dark and rainy with gale force winds at Svolvær. The archived weather data showed substantial turbulent kinetic energy in the area, which from a meteorological point of view means intense turbulence and wind shear.

Wind measurements taken at Svolvær’s runway were in line with the weather data. That said, the equipment wasn’t capable of showing wind shear, only predicting that it might be likely. The Aerodrome Flight Information Service doesn’t automatically offer detailed wind reporting. On final approach, the pilot is expected to request further windchecks or ask for continuous wind readings if they feel it is necessary. The AFIS duty officer offered the current wind reading while the aircraft was downwind but did not volunteer any further information.

There are standard procedures for an approach with risk of wind shear but the flight crew did not follow them, presumably because they didn’t realise that’s what they were flying into. The aircraft did not have the capability of detecting wind shear and the warning in the company briefing was for the last part of the final approach, which they had not yet reached.

Both pilots remember the weather and that as they were approaching Svolvær, the wind dropped to about 10-12 knots, well within operational limits.

They started the instrument approach, following the standard procedure for south-westerly winds. This procedure is to approach northward (LOC 01) down to the minimum descent altitude of 580 feet. At that point, if the aircraft is clear of cloud and the crew has good visibility, they can perform a visual circle east of the airport and position to land on runway 19.

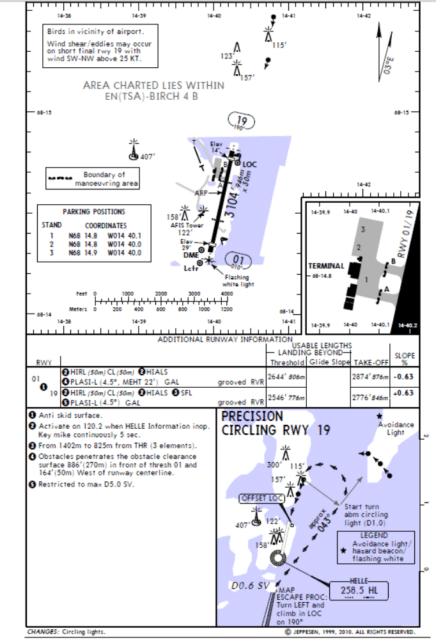

Widerøe’s map of ENSH 11 Feb. 2011 (actual map not available), showing “Precision

Widerøe’s map of ENSH 11 Feb. 2011 (actual map not available), showing “PrecisionCircling RWY 19? in the lower right-hand corner. The circling lights in the northeast and at the

final approach were installed after the incident.

Widerøe had a special permit from the Civil Aviation Authority Norway which allowed them to use “precision circling”.

The report explains this.

This means, among other things, that one accepts a smaller extent of the obstacle-free area compared with what is the ICAO standard for this category of aircraft. This allows a lower minimum altitude for circling.

A number of trade-offs and risk assessments form the basis. For example, it is desirable to get so close to the airport during circling that the likelihood of losing visual references is reduced. One will also want, insofar as possible, to avoid having to make a descent based on visual references, since that makes it difficult to maintain the correct energy on the aircraft throughout the circling. The objective is to avoid ending up too high on the short final approach.

At Svolvær, the minimum altitude was 580 feet.

The Dash-8 cleared the clouds well before this and the flight crew had the airport lights in sight. They descended to 600 feet and continued as planned, with a visual circle above the fjord.

The roles of the flight crew are clearly defined. As they circle, the Pilot Flying, in this case the captain, looks out and flies the aircraft based on visual references. The Pilot Monitoring, the first officer, focuses on the instruments and calls out any deviations from the planned speed (110 knots) or the flight path.

The flight crew prepared for landing on the downwind leg, lowering the landing gear and setting the flaps to 15°. The captain knew that the wind would be pushing the aircraft away from the airport and towards the mountains, which were marked with white flashing avoidance lights. The AFIS duty officer agreed to continue giving them wind readings as they approached runway 19.

The flight crew did not discuss the Svolvær approach procedures for a risk of wind shear.

As they entered the turn towards the final approach, they flew into a severe down draft. The Dash-8 was forced downwards and lost speed.

It’s not completely clear what happened next. There are substantial differences in the accounts given by the captain and the first officer and also some differences between the reports they made at the time and the interviews four years later.

After the event, Widerøe’s flight operations management interviewed the crew about the severe wind shear they encountered. At the time, they noted that the crew had done the right thing by interrupting the approach, although the reaction to the incident was seen as somewhat excessive (severe nose down, significant engine power, acceleration to a high speed in the recovery). However, the flight operations management were happy that the correct actions had been taken and that the crew had regained control.

Some flight data information was reviewed at the second meeting, after which, the captain was asked to submit a more detailed report, which he did.

Based on the meetings, Widerøe management decided that this was not a serious aviation incident and thus there was no need to report it to the Accident Investigation Board.

They submitted their reports to the Civil Aviation Authority who also did not see any grounds to involve the Accident Investigation Board.

The first officer saw things differently. He requested a copy of the plotted flight data parameters. Then he submitted a further report to highlight the serious nature of the incident. That report was not entered into the management system and was never submitted to the Civil Aviation Authority. Widerøe did not see any need to investigate further.

Two years passed but the first officer never forgot that night. He left Widerøe and gave up his career as a pilot. In December 2012, with nothing left to lose, he contacted the CAA and the Accident Investigation Board. The CAA asked the Accident Investigation Board to look into it. The Accident Investigation Board also concluded that it was not necessary to investigate further. Their main issue was that the first officer had waited until he was no longer working at Widerøe to report it. They warned Widerøe that there were issues with their reporting policies and that operators needed ensure that pilots were aware that they could report a case to the authorities if they disagreed on what happened or the severity of the occurrence.

It was 2015 when Aviation Herald broke the story, attracting attention to the first officer’s concerns. The first officer sent the flight data to Aviation Herald which certainly seemed to confirm that this was worth an investigation. Amid media pressure, the Norwegian Accident Investigation Board conceded that “the incident could contain a greater potential for learning than first assumed.” They initiated their investigation, finally, in March 2015. Shortly thereafter, they reclassified the case as a serious aviation incident.

In the interview from the second investigation, the captain remembered clearly the first officer calling “Check speed” and that in response, he had adjusted the engine power, but only marginally, as he didn’t believe that their speed had deviated significantly from the targeted 110 knots. He conceded that they had not discussed increasing the airspeed to counter the effects of the strong winds.

The captain then disengaged the autopilot and started the base turn. The flaps still needed to be set to 35° on final approach but other than that, the Dash-8 was configured for landing.

He remembers starting the base turn after he had passed the airport. He saw the airport lights behind him, to the left (approximately 45°, a normal base turn). It was dark and he could not see the sea beneath him or the horizon in the distance. However, he wasn’t concerned: the airport lights were visible on the left and he could also see the red lights warning of obstructions a few kilometres north of the airport. He planned to continue at 600 feet until they were lined up with the runway for landing.

But, he said, he hadn’t quite started the turn when he first noticed that something was out of the ordinary. The first officer had called “check speed” twice and then suddenly the aircraft began to shake and there was a sudden drop. The captain said he corrected for this immediately.

Although he clearly remembers applying full power, it had no effect. The airspeed continued to drop and he had the feeling as if the Dash-8 were being sucked or pushed downwards. He pushed the controls forward to prevent stalling. When he pulled back again to climb, the stick shaker activated, warning of an impending stall.

He immediately eased up on the climb to build up more speed. At the same time, he saw red obstruction lights in front of him. He glanced at the altimeter and his recollection is that it showed about 300 feet (90 metres).

He could not remember if he noticed the stick shaker before or after he pushed the controls forward. He knew that they were low. He focused on one of the red lights and kept flat, in order to build up speed so that he could climb away without risking a stall. He felt he knew where the terrain was and he carefully kept the aircraft level so that they could build up speed: he wasn’t sure how long he “held the aircraft down” but estimated that it was four or five seconds.

Once they had regained a safe airspeed, he started climbing and was confident that they would pass over the obstruction marked with the red light at a safe altitude and airspeed.

Then, to his surprise, the first officer took control and initiated a steeper climb.

The captain saw no need for this. However, they’d gained enough airspeed and the situation was under control, so he didn’t argue it.

None of this had come out in the original reports that Widerøe submitted to the Norwegian Civil Aviation Authority in 2012. These reports, generated as part of Widerøe’s deviation management system, were based on the captain’s description and focused on possible overtorque from the missed approach, which was caused by windshear. The Widerøe reports did not mention how much altitude the aircraft had lost or that the first officer had taken over the flight controls. Now, it was clear that the first officer had taken control at the same time as the engine power was increased from “full” (approx 100% torque) to maximum (approx 120% torque).

Finally, five years after the event, the Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) interviewed the first officer. He remembers that he was monitoring the instruments and first called out “Check speed” while they were still downwind. He called again after the captain had entered the circling pattern.

He said that the captain had not corrected sufficiently for the conditions and that they needed to get the airspeed up further to be safe. He expected that they would lose altitude in the turn and that as a part of the requirement for a stabilised approach, they needed to have wings level no later than when they reached 300 feet.

As they started that turn for the final approach, he was startled as the controls started shaking. Realising that the stick shaker had triggered, he was ready to react to the impending stall. To his surprise, the captain did not react and made no callouts. Then the aircraft’s nose dropped and he said that he “stared straight down onto the black sea,” with a red light on a small island visible in the dark.

He remembers clearly that the captain was holding the stick in a neutral position, as if he had frozen. They might have been as low as 150-200 feet above the water, he said. The first officer was pretty sure that he called out “my controls” as he grabbed the stick and pushed the power levers fully forward (approximately 116%) until the aircraft stopped descending. He had to pull the control column back with both hands with considerable force and he remembers thinking that there was no way this could end well. The aircraft “eventually” started to climb to a safe altitude.

It’s important to note that the first officer’s report of the events leading up to him taking control of the aircraft is very similar to the original statement he made when interviewed by management in 2010, whereas the captain’s version had a number of differences. However, that could simply be that it had been a relatively unimportant moment to the captain, who was mostly surprised at the first officer’s overreaction, and quite a traumatising experience for the first officer, who had seconds in which to realise that his captain was not responding and he needed to take control of the aircraft.

Although the investigators could see what had happened based on the recorded flight data, they had no way of determining which pilot did what and exactly when. They created an animation to try to show the sequence of events.

Clearly, the aircraft suddenly lost a significant amount of speed and altitude as a result of wind shear. At one point, the aircraft was just 83 feet (25 metres) above the ground. In an attempt to recover from the windshear, the aircraft was exposed to high g-forces and the engine torque limits were exceeded. The flight crew recovered in time and continued to Leknes Airport, where they landed normally.

But did the captain respond correctly and the first officer overreact after the situation was resolved? Or did the captain freeze up, with the first officer’s intervention key to the recovery?

The report summarised the differences in the two men’s sequence of events as follows.

The commander’s statement

Gave full engine power and lowered the nose of the aircraft when airspeed was lost and the aircraft started to shake. The stick shaker activated during the climb and therefore intentionally kept the aircraft down and accelerated at a safe altitude towards a red obstruction light. Airspeed increased and climb was initiated before the first officer unnecessarily took over the controls.

The first officer’s statement

“Stick shaker” activated. The nose was lowered as a result of external influence, without corrective measures being implemented by the commander. Instinctively took over the controls and increased engine power to avert crashing into the sea.

But those statements were made several years after the incident in question and this would clearly have an impact on the recollections of the event.

It is human nature, in retrospect, to wish one had performed the task well, which may also affect a person’s memory over time.

And although the flight recorder data shows that the incident lasted just ten seconds, both pilots and the cabin crew member were sure that it had lasted much longer.

The flight recorder data can confirm airspeed, altitude, flight attitude, engine power and g-loads but not when the stick shaker was activated or who moved the flight controls.

However, the report puts forward one hypothesis that explains how both pilots were telling the truth, at least as they perceived it.

The conditions were right for for a visual illusion, the black hole illusion which is known to occur during nighttime approaches at remote locations where isolated lights are the only visual cue. A pilot suffering from this perceptual illusion during the approach will unknowingly fly a dangerously steep descent angle and overestimate their height .

The black hole illusion is not pilot error. It’s a perceptual limitation of how humans perceive depth and visual angles. Spatial disorientation leading to loss of control is relatively rare but often fatal.

The problem, of course, is that it is rarely possible to prove whether such a shift in perception actually took place. Even in this instance with a happy ending, there is no real way to know whether the captain was suffering from an illusion which caused him to misinterpret the situation.

The AIBN considered the following sequence of events to be likely.

The aircraft was exposed to severe wind shear. The captain attempted to recover by applying full power, but aircraft continued to lose altitude and speed. The stick shaker activated, at which point the captain pushed forward on the control column and then pulled back again to level out. The aircraft accelerated but the nose was still 14° below the horizon. At this point, the captain was focusing on regaining control of the aircraft and remembers seeing the red light ahead of him, but not the sea below. He believed that the aircraft had started to climb. They were building up speed and the captain may have perceived the aircraft as climbing but in all actuality, they were still descending. The first officer realised that the captain wasn’t reacting to the continued descent and they were in danger. At the lowest point, the aircraft was just 83 feet above the water. The first officer was focused on the instruments and thus, he didn’t suffer from the visual illusion, which is why the two pilots had such different perceptions of the same event. The first officer took control and applied max power.

In the end, said the AIBN, it didn’t actually make a difference, crew cooperation meant that the response to the wind shear event was appropriate. Between the two of them, they saved the day: the airspeed increased, loss of altitude was halted and the aircraft climbed away.

There is no doubt that the climb was initiated by the commander, but there is uncertainty whether it was he or the first officer who intensified it. If the first officer intervened at Time 103201.3, there is nevertheless no one who knows how the commander would have moved the controls in the following seconds if this had not taken place. This is a fact regardless of whether the commander was experiencing a sensory illusion or not.

However, the AIBN also admits that it wasn’t a foregone conclusion.

AIBN is of the opinion that the joint actions of the crew prevented an accident when the aircraft was exposed to unusually strong wind shear at low altitude. Marginally longer response time and/or less resolute application of engine power would probably have resulted in collision with the sea.

You can read the full report here: Report on Serious Incident at Svolvær Airport Helle, Norway on 2 December 2010, involving Bombardier DHC-8-103, LN-WIU operated by Widerøe’s Flyveselskap AS

It is hard not to read that conclusion as a continued justification as to why they didn’t investigate initially, even though the AIBN was not contacted at the time and only had partial information when they finally heard about the event from the first officer. It is clear that only the continued pressure from Aviation Herald led the AIBN to take a better look.

In the process, they found serious issues with Widerøe’s reporting and a management culture that meant that the first officer did not escalate until he had left Widerøe. In addition, the investigation highlighted issues at Svolvær which could help a future flight crew in similar conditions. The incident clearly required an in-depth analysis and it is only a shame that the industry had to lose the skills of a good pilot to finally get it.

I do think maybe I shouldn’t have attempted my first audio post on an incident that includes a lot of place names that I don’t actually know how to say! So a special “sorry” to my Norwegian readers on that score.