Contributing Editor James Kightly profiles Fokker F.VIIb VH-USU – unquestionably one of the most important surviving aircraft of the long distance record era. The operation by the HARS Aviation Museum of the Fokker F.VIIb Trimotor [...]

Contributing Editor James Kightly profiles Fokker F.VIIb VH-USU – unquestionably one of the most important surviving aircraft of the long distance record era.

The operation by the HARS Aviation Museum of the Fokker F.VIIb Trimotor VH-USU replica ensures the type is seen in the sky by the public. Amazingly, the original, historic Fokker VH-USU survives.

The originl Fokker F.VII was ordered by expatriate Australian explorer George Hubert Wilkins for his Arctic expedition in 1926 and named the ‘Detroiter’. To maximize the fuel and payload he requested the new larger wing version of the type, becoming the first Fokker customer for the F.VIIb-3m, the ‘b’ for the larger wing, the ‘3m’ for the trimotor configuration.

The Fokker as the ‘Detroiter’ in 1926 with Sir Hubert Wilkins. Anthony Fokker knew the importance of publicity! [Via Netfield Publishing]

The Fokker as the ‘Detroiter’ in 1926 with Sir Hubert Wilkins. Anthony Fokker knew the importance of publicity! [Via Netfield Publishing]

The expedition suffered multiple setbacks including someone being killed when hit by the aircraft’s propeller and a broken undercarriage as the result of a bad weather landing in Alaska.

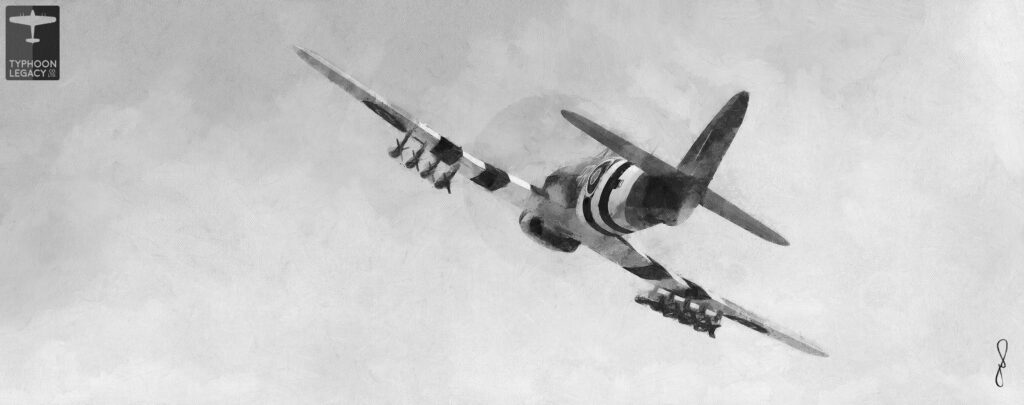

The ‘Southern Cross’ originally bore the US civil registration 1985 (not a year!) Registered in Australia as G-AUSU in 1928, this changed to VH-USU in April 1931. Today it’s in its original Pacific record scheme. [J Kightly]

The ‘Southern Cross’ originally bore the US civil registration 1985 (not a year!) Registered in Australia as G-AUSU in 1928, this changed to VH-USU in April 1931. Today it’s in its original Pacific record scheme. [J Kightly]

It was bought without engines or instruments by Charles Kingsford Smith – ‘Smithy’, and Charles Ulm with the express purpose of making the first Pacific flight from California to Australia. New engines and long-range tanks cost money, but two fundraising attempts at the world endurance record fell frustratingly short of the hours required aloft. The project was in serious difficulties until the Fokker was bought by American philanthropist Allan Hancock, who loaned it back to Smithy and Ulm.

The two men most associated with the Fokker VH-USU, seen at Mascot airfield, NSW, Australia on 10 June 1928; left, Charles Kingsford Smith ‘Smithy’ and right, C.T.P. Ulm. Neither were to survive the 1930s pioneering record era, both being lost on record-attempting flights. [State Library of New South Wales No: FL3326640]

The two men most associated with the Fokker VH-USU, seen at Mascot airfield, NSW, Australia on 10 June 1928; left, Charles Kingsford Smith ‘Smithy’ and right, C.T.P. Ulm. Neither were to survive the 1930s pioneering record era, both being lost on record-attempting flights. [State Library of New South Wales No: FL3326640]

On 31 May 1928, Kingsford Smith, Ulm, and two Americans, navigator Harry Lyon and radio operator James Warner, took off from Oakland, California, stopping in Hawaii before a marathon 34 hour leg to Fiji. The Southern Cross finally touched down at Eagle Farm Airport in Brisbane, Queensland, on 9 June to the reception of a 25,000-strong crowd. Hancock gifted the aircraft to Smithy and Ulm, and they flew the aircraft on to Sydney.

Not resting on these laurels, on 8 August 1928 Smithy and Ulm made the first nonstop transcontinental flight in Australia from Point Cook in Victoria to Perth, WA. Navigator was Harold Litchfield and radio operator New Zealander Tom McWilliams. Kingsford Smith, Ulm, and P.G. Taylor then made the first nonstop Trans-Tasman flight on 10–11 September 1928 in 14 hours and 25 minutes. There, 30,000 people greeted them upon landing at Wigram Aerodrome in Christchurch. After barnstorming in New Zealand, they flew back to Australia.

The Fokker F.VIIb ‘Southern Cross’ at Eagle Farm following the first Pacific Ocean crossing, 9 June 1928. [QLD State Archives]

The Fokker F.VIIb ‘Southern Cross’ at Eagle Farm following the first Pacific Ocean crossing, 9 June 1928. [QLD State Archives]

The next record attempt was where it all started to go wrong. In May 1929 Smithy took off from Sydney heading to the UK, but was forced to land in North Western Australia, being lost for twelve days. The deaths of searchers Anderson and Hitchcock led to a media attack that unfairly tarnished Smithy and Ulm’s reputations, overshadowing their subsequent flight to England in a record 12 days and 18 hours.

Smithy managed another remarkable first in the Southern Cross in June 1930, when he and a hired crew flew the Atlantic from Ireland to Newfoundland, then across the USA, back to where he’d started the Pacific flight and became the first airman to circumnavigate the globe with a route in both hemispheres – not just one.

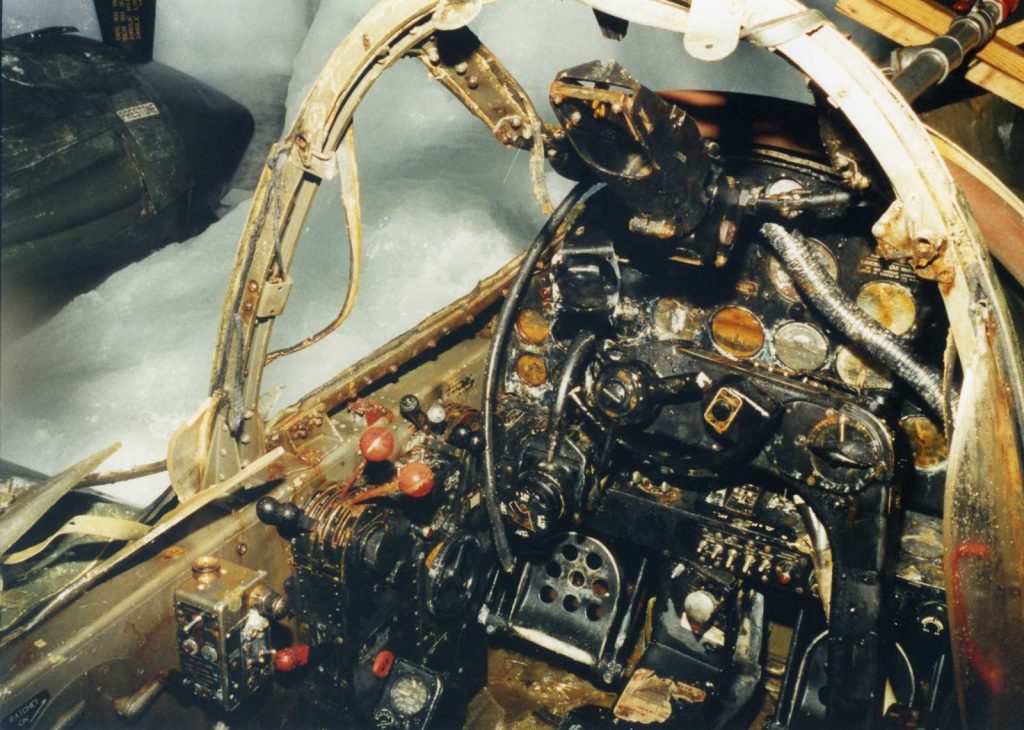

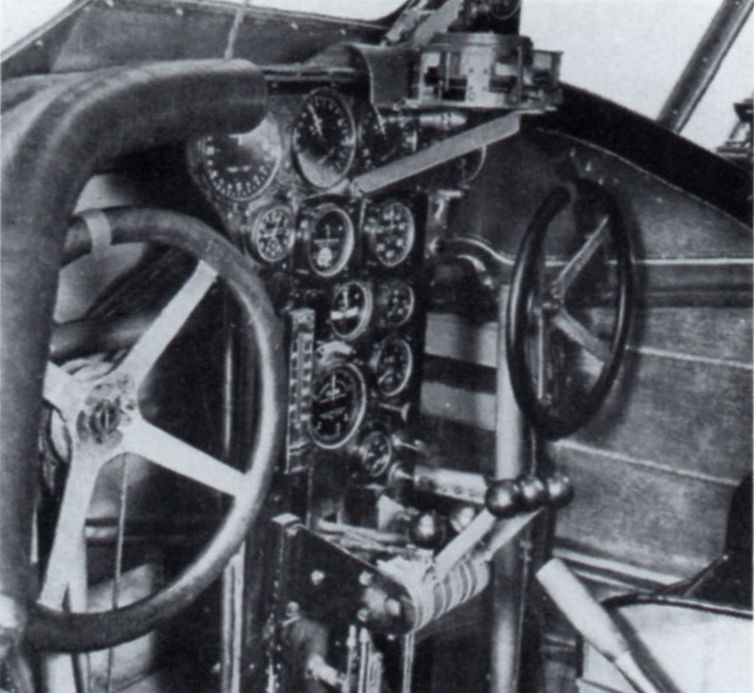

The cockpit of Fokker F.VIIb VH-USU. [Author’s Collection]

The cockpit of Fokker F.VIIb VH-USU. [Author’s Collection]

In 1932 (and again in 1935) Smithy barnstormed the now genuinely old ‘Old Bus’ around Australia to raise funds for other records (and the ever hoped for) airline. And there was one last – and what proved most dramatic – hurrah for Smithy and the Fokker. On 15 May 1935, he, John Stannage and P.G. Taylor set off for New Zealand with a commemorative airmail. Six hours out, the center engine’s exhaust broke, a fragment smashing the starboard engine’s propeller. Worse, the port engine was running low on oil, so Taylor climbed out in flight onto the wheel struts and, using a thermos and a suitcase, transferred oil from the unusable engine to the port one, and they returned to Australia safely.

Soon after, and shortly before Kingsford Smith’s death in 1935, he sold the Southern Cross to the Commonwealth of Australia, for A£3,000, to go on display in a proposed museum: a remarkably far sighted deal by both parties in an era that rarely valued historic aircraft. Refurbished and flown by Bill Taylor and an RAAF crew, it was brought out of retirement briefly in 1945 for the filming of the movie ‘Smithy’, but otherwise it was stored until the NSW branch of the Royal Aero Club had placed it on show in October 1947 at Bankstown, and a brief show in Sydney’s Hyde Park in September 1957, until the Fokker was put on show in the Sir Kingsford Smith Memorial in 1958. Restored again in 1985, it was put on permanent display on Airport Drive, at the new Brisbane Airport, Queensland.

Smithy and his fellow pioneers flew more record-setting long distance flights than any other aircraft of the era in the ‘Southern Cross’. This was latterly due in part to Smithy being unable to secure a better aircraft, thus falling back on using his ‘Old Bus’ as a result. Today, like the Smith brothers’ Vickers Vimy at Adelaide airport, it’s well known to aviation enthusiasts worldwide, but the Southern Cross’ current location has left it far from the ken of the traveling public, who really are the beneficiaries of its pioneering airmen.

[In December 2023, the Historic Aircraft Preservation Society (HARS) flew the replica of the Fokker once again, after a dedicated 20 year restoration. Full details here.] A portrait of Smithy and Ulm and the chronometer used on one of the aircraft’s many record flights in front of this historic machine. [James Kightly]

A portrait of Smithy and Ulm and the chronometer used on one of the aircraft’s many record flights in front of this historic machine. [James Kightly]