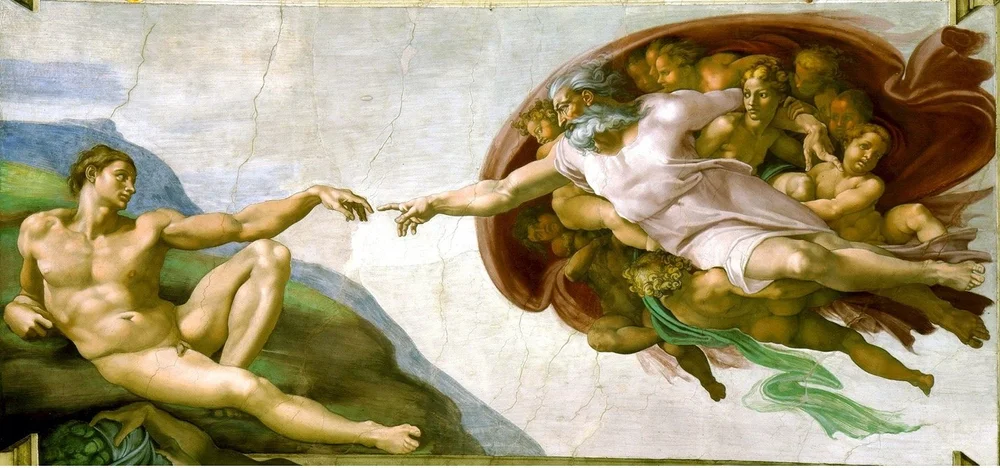

Picture God. What do you see? Perhaps Michelangelo’s Ancient of Days on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, creating Adam with the touch of a finger and bringing him to life. Or perhaps William Blake’s judgmental God banishing Adam...

Michelangelo. “The Creation of Adam,” Sistine Chapel (ceiling fresco) c. 1511.

Vatican City, Italy.

Picture God. What do you see? Perhaps Michelangelo’s Ancient of Days on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, creating Adam with the touch of a finger and bringing him to life. Or perhaps William Blake’s judgmental God banishing Adam from the garden of Eden, a relief etching from 1795, currently on display in London’s Tate Collection.

William Blake. God Judging Adam (relief etching, ink and watercolor on paper, 1795.

Tate, London.

Turning to scripture, we may envision a trio, God and two angels cloaked as men visiting Abraham beneath the great tree of Mamre, having dinner with him and telling Abraham that Sarah would bear him a son in her old age, as Sarah herself eavesdrops on the conversation from the kitchen.

Jan Victors. Abraham Entertaining the Three Angels (oil on canvas), c. 1640.

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

I’ve seen countless portrayals of God in art, spanning the centuries . . . but honestly, all seem fanciful and wholly inadequate. God is infinitely greater than our imagination can conceive. But here’s a start: in St. Paul’s epistle to the Romans, he says: “since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made . . .” (Romans 1: 20). That takes us directly back to the opening of Genesis: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty [tohu wabohu, “welter and waste”], darkness was over the face of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light” (1: 1-3).

To grasp the import of scripture’s opening words we have to abandon our anthropomorphic concept of God and expand our vision far beyond the creation of our own rather insignificant little planet to encompass all of creation, all of the vast and infinite universe. In Robert Alter’s brilliant translation of Genesis, he renders the opening line as, “When God began to create the heaven and earth, and the earth then was welter and waste and darkness over the deep and God’s breath hovering over the waters, God said, ‘Let there be light.’” Alter’s rendering shocks and disorients those of us born and nurtured on the majestic King James version of 1611, which reads “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light; and there was light.” We are so used to hearing the latter (and variations upon it) that to us it is the correct reading.

But re-examining the Hebrew text and its grammatical nuances leads us to shift our perspective. The grammatical crux lies with ???????? [ray-sheeth’, “beginning”], which is bound to an unmarked relative clause: there is no definite article “the,” so grammatically ???????? is linked to what follows.[1] If that is the case, then Genesis 1: 1 marks the beginning of a process, not an absolute singular event; hence, Alter’s translation: When God began to create the heaven and earth . . ..” And this opens up a profound and astonishing vision of creation.

We know that the earth is one of eight planets orbiting the sun in our solar system; there are at least 100 billion stars (suns) in our galaxy, each having at least one planet orbiting them; and astronomers estimate that there are around two trillion galaxies in the observable universe. To grasp the magnitude of that statement, understand that our own Milky Way galaxy with its 100 billion stars is a barred spiral galaxy measuring roughly 87,000 light years in diameter and about 1,000 light-years in thickness at its spiral arms. Pause to consider that light travels at 186,000 miles per second, run those numbers, and that suggests the staggering magnitude of our own galaxy’s size . . . which is only one of two trillion galaxies!

[1] Robert D. Holmstedt. “The Restrictive Syntax of Genesis 1: 1,” Vetus Testamentum 58 (2008), pp. 56-67. See, too, Martin F. J. Raasten. “First Things First: The Syntax of Genesis 1: 1-3,” Studies in the Literature and Jewish Culture Presented to Albert Van Der Heide on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday, ed. by Martin F. J. Baasten and Reinier Munk. Springer: Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 2007.

Map of the Milky Way Galaxy with the constellations that cross the galactic plane in each direction and the known prominent components including main arms, spurs, bar, nucleus/bulge, and notable nebulae and globular clusters. The image is a composite based on data from Gaia, the European Space Agency’s observatory, launched in 2013 and expected to operate through 2025.

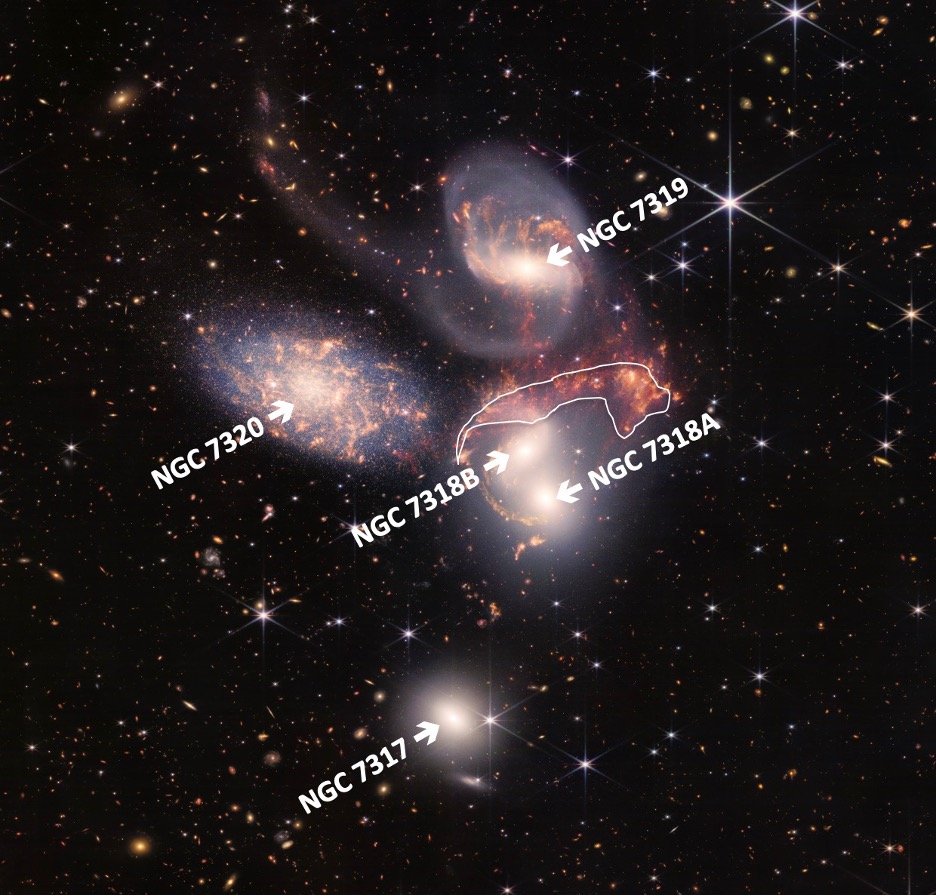

Viewing our own tiny solar system within the Milky Way Galaxy—little more than a pin-prick on the image above—should create a sense of awe and wonder. But let’s take another giant step outward. NASA’s James Webb telescope launched on 25 December (Christmas Day), 2021, went operational on 11 July 2022 and it sent its first full-color images and spectroscopic data back to earth on 12 July 2022, an event broadcast live on television at 7:30 AM (PDT). Among the images was this of Stephan’s Quintet, a set of five galaxies, four of which interact.

The left galaxy, NGC 7320, is actually much closer to us than the rest of the group. NGC 7320 is about 40 million light-years away from our planet Earth, while the other four are roughly 290 million light-years away. Again, the distance is staggering! The four colliding galaxies—NGC 7319, 7318 A, 7318B and 7317—are pulling and stretching each other in a gravitational dance. I have outlined the shockwave caused by the colliding gravitational forces. Scattered across this two-dimensional image, we see bright stars in the foreground with diffraction spikes emanating from them, as well as dimmer stars in the background, many of which are more distant galaxies.

Here we have another image from the Webb telescope, this of the Eagle Nebula, dubbed the “Pillars of Creation,” interstellar gas and dust that is birthing stars, some 7,000 light-years away from earth. This is a dazzling image!

The Hubble telescope first captured this image in 1995 and again in 2014, but the Webb image in near-infrared light, which is invisible to our eyes, offers stunning detail of newly-formed stars “glistening like dewdrops among floating, translucent columns of gas and dust,” as NASA describes it. The name “Pillars of Creation” comes from an 1857 sermon by Charles Spurgeon titled “The Condescension of Christ,” in which Spurgeon speaks not only of the physical world, but of the force that binds it all together. In his sermon he says of the birth of Christ: “And now wonder ye angels, the Infinite has become an infant; he, upon whose shoulders the universe doth hang, hangs at his mother’s breast; He who created all things and bears up the pillars of creation, hath now become so weak, that He must be carried by a woman!”

Clearly, the universe is not static, but a work in progress: stars are born (as we see above) and stars die; galaxies collide and interact; the universe is alive, active, in motion, a never-ending act of becoming. Robert Alter is correct—grammatically and theologically—in translating Genesis 1: 1 as “When God began to create the heaven and earth . . .,” when God began a process that is still in motion even to this very day.

Now, come back to Earth, to our home, to our own little blue marble in the lunar sky.

Earth rising over the lunar horizon, a photo taken on 24 December 1968 by Apollo 8 astronaut William Andres.

God creating humanity is but a tiny, infinitesimal act in the grand drama of the universe. And yet, he created each and every one of us, forming us in the womb and from the moment of conception giving us a unique genetic coding, inherent talents, gifts and abilities. He placed each of us at a particular moment in time and place, and he implanted in us a desire to know him, to seek him out and to enter into an intimate, loving relationship with him. Why did he do that? For the same reason he created and continues to create the universe: God is a creator, and the very act of creating—be it galaxies, stars, planets . . . or us—gives him pleasure and satisfaction, just as a composer derives pleasure and satisfaction from composing a symphony, a concerto, a song, or a poet from composing an epic, and elegy or a sonnet. As we read in St. Paul’s epistle to the Ephesians: “In love he predestined us for adoption to sonship through Jesus Christ, in accordance with his pleasure and will” (1: 4-5). That is an astounding statement. God almighty, creator and maintainer of the infinite universe, the one who made quasars, pulsars and even now is creating stars, desires to have an intimate, loving relationship with us as his sons and daughters. That is absolutely staggering! And for that, we can only stand in awe and give him thanks and praise.

Picture God? St. Paul does it best: “[S]ince the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made” (Romans 1: 20).