Lager (or low-fermentation) beers are undoubtedly the most popular and commercialized beers in the world. Despite being frequently reviled by the consumer of craft beer, this kind of beers have been experiencing a something similar to a rebirth in...

Photo © Cervesa Montseny

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL AQUÍWHAT IS A LAGER BEER?

Lager (or low-fermentation) beers are undoubtedly the most popular and commercialized beers in the world. Despite being frequently reviled by the consumer of craft beer, this kind of beers have been experiencing a something similar to a rebirth in the recent years within an increasingly wide circle of fans.

Lagers vs Ales. Source: worth1000beers.com

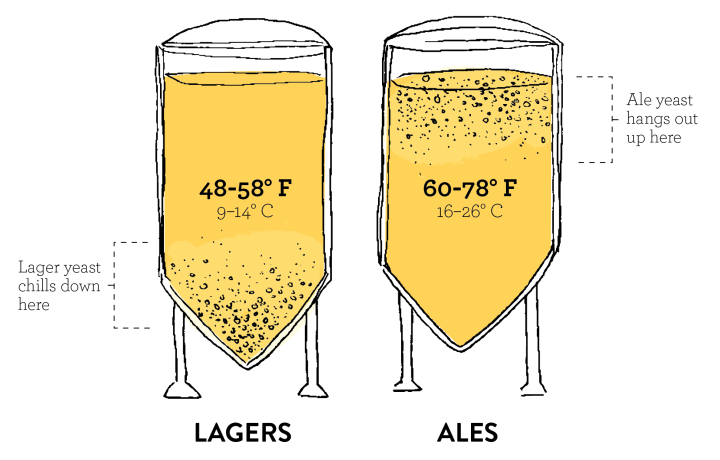

One could say that the main difference between lagers and ales (or high fermentation beers), is in the yeast. Saccharomyces pastorianus or carlsbergensis is used to brew lagers, while to brew ales, the yeast used is Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The first one works at low temperatures and takes weeks to ferment, and the latter one works much better at high temperatures and can complete the primary fermentation in just a few days.

We also find a differentiating element in its flocculation capacity: in lagers, the yeast (which cells are much larger) tends to fall down to the bottom of the fermentation tank, while in ales, the yeasts that carry out the fermentation process are usually active at the top of the tank.

Although the most famous variety of lager is the Pilsner style, which emerged in the city of Pilsen in 1842, there are many others, such as Bock, Märzen, Helles, Vienna, Schwarzbier or Munich Dunkel beers.

TALKING WITH JORDI LLEBARIA, BREWER AT CERVESA DEL MONTSENY

In order to shed more light on this beer family, I had the opportunity to speak with Jordi Llebaria, head brewer of Cervesa del Montseny, a pioneer brewery in the craft beer scene in Spain.

But before discussing technical aspects, I consider it essential that we highlight the important role that Jordi has been playing for years in the craft beer field in our country.

Jordi tells me that his beer adventure began in 2002, “with a group of friends from the science faculty of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). We were united by the passion for this drink and the desire to do things with our hands. The result was the creation of a collective of homebrewers that culminated in the birth of Cerveza Maquis. Maquis was, and still is, a learning laboratory and a refuge where we can express ourselves with beer."

On a professional level, its history has always been linked with Montseny Brewing Company. He joined in 2007 when it was founded, as an assistant to what was then the brewmaster, Pablo Vijande: “Turning your hobby into a profession was an opportunity that I could not refuse. A few years after entering, I took over the controls of the brewery, and that was when new adventures began; the creation of new recipes, collaborations, national and international festivals ... ”.

Jordi currently has another long-established brewer in his team, Albert Sànchez, and thanks to his help, he has been able to spread his efforts in various fields related to beer production, and also hold the position of head of quality and food safety.

In a way, talking about Montseny is a little like talking about ourselves. Despite being a brewery which career began only fourteen years ago, the tanks overseen by Jordi have produced authentic modern classics, such as the award-winning Imperial Stout “Montseny Mala Vida” and its various versions aged in different types of barrels, or the famous Montseny Aniversari IPA.

Also, we cannot just ignore the paradigm shift in the commercialization and democratization of craft beer that, in my view, meant the entry of what was the best brewery of the year in the first edition of the Barcelona Beer Challenge (2016) in the hotel and restaurant sector. Thank you Jordi for enlightening us and participating in C R A F T E D!

Photo © Øhm Sweet Øhm

Ø: Broadly speaking and at an organoleptic level, could you point out what are the main differences between lager beers and ale beers?

Jordi: First of all, it must be taken into account that both families are enormously broad and host a multitude of styles, so I consider it necessary to contextualize that I am going to refer to the most representative examples. In general, the use of lager fermentation strains and the fermentations at low temperatures associated with this style translate at an organoleptic level in beers with lower levels of esters (compounds associated with fruity flavors). We commonly speak of cleaner fermentations, with less contribution of fermentation byproducts that affect the taste of the final beer.

Ø: Is it true that brewing lagers - and doing it well - is much more complex than brewing ales? If yes, why?

Jordi: Speaking in these terms always seems risky ... in my case and taking into account my experience at Cervesa del Montseny, where the ales have been our main focus of attention, I must admit that it is true and that the step to make a German Pils was a new challenge. But I suppose that a German brewer used to making lagers would have the opposite problem ... What is certain is that lager beers, having cleaner fermentations and commonly being soft and light beers, are much more sensitive to showing possible defects than in other styles where they would be easily hidden.

Equally important is that the style by definition requires meeting much stricter visual requirements in terms of clarity, brightness ... and that at the same time, we must maintain a correct foam retention. It seems obvious and simple, but it is still an added headache for the brewer.

Ø: If we think about the different phases or processes of its elaboration, in the types of yeast that should be used, in the control of temperatures during boiling and fermentation, in the ingredients (types of malts, hops, profile of the water) etc. What would you say, according to your experience, are the keys to achieving a textbook lager?

Jordi: Linking with what I said before, and if we take into account that for a lager we are looking for a combination of elegant nuances, freshness and something to be enjoyed with time, then we should go to the subtleties. A good base of quality ingredients would be the first pillar, since it is through this style that a good pils malt or German or Czech noble hops are expressed in their greatest splendor. A staggered mash is recommended, although if you use well-modified quality malts, I don't think it is an essential aspect either. Much attention has to be put in the boiling process, it must be very vigorous to favor the volatilization of many precursors of compounds that would be undesirable in the final beer (DMS is the most common).

With the cold wort we would go to the fermentation stage, where we have to pay special attention. We have to maintain the primary fermentation between 10 or 12º C depending on the strain used and the profile we want to achieve. As we approach the end of fermentation, the temperature must be allowed to rise to around 15ºC for the diacetyl resting stage, since its absorption by the yeast is more favorable at high temperatures. After this resting time, and with the beer already fermented, this is when we must proceed to reduce the temperature again to start the lagering stage.

I would like to make a note regarding the temperature rises and falls of our lager during fermentation: it is advisable to avoid gradients that exceed 3ºC a day so as not to stress or damage the yeasts that are still active.

Ø: Contrary to what happens with ales, after the first fermentation, the maturation or “lagering” process in lager beers is greater. Could you explain to us what this resting phase consists of, how many days it usually lasts, and how the beer evolves throughout this process?

Jordi: Once the primary fermentation is finished and after the resting phase of the diacetyl, that is when we would go on to cool the beer to temperatures close to freezing, then the phase known as lagering starts. This is nothing more than a maturation stage, in which subtle biochemical and physical processes take place, which mold the beer to the smooth and clean flavors typical of the style. This stage should last a minimum of 3 weeks; although one, two or even three months could be recommended and be more than beneficial, as long as the storage conditions are adequate (absence of oxygen and cold).

During this time, acetic and lactic acids, acetaldehyde (flavor associated with “green” beer), as well as the remaining volatile diacetyl, are reduced. In turn, we promote the precipitation of both the yeast in suspension and the residual colloidal complexes, thus reducing haziness and improving the beer in terms of its stability.

Ø: The “Lager” from Montseny, which name in addition to being a declaration of intent and a tribute to low-fermentation beers, is a German Pils. How is this style different from a Czech Pilsner?

Jordi: In general and from a technical point of view, German and Czech lagers differ by using different yeast strains and different ranges of fermentation temperatures. This translates into the final beer both in body and in flavor: Czech Pilsner tends to have a fuller body and a more complex flavor richness than German Pils, which by definition is considered a very refreshing and high-quality beer with a high drinkability.

Image © Cervesa Montseny

Also to say that the specific case of German Pils, within the broad family of German lagers, is a more hop-oriented style, with a more pronounced bitterness and greater presence of the character of German hops both in flavor and aroma.

Ø: Finally, I would like to know what you think about the “dictatorship” of the IPAs - in all its variants -, which have been setting the pace of the craft market for years, and, on the other hand, if you think that the classic styles will win again the prominence that many brewers have long been claiming and longing for.

Jordi: Dictatorship? I understand the question but I don't see it at all like that. At the end of the day, it is the consumer who is setting the trends every time he decides which tap to take a pint from. This is not an orchestrated strategy to sell beers at a higher price, rather it is the natural response to the enormous advance that is taking place in new varieties of hops. This is the fundamental reason for the paradigm shift in the beer industry. And the result is tremendously attractive, right?

It is true that under this paradigm shift many classic styles have been designated to the background, or it may seem like that if we look at the taps of the main craft beer bars. Even in Montseny, where we have always had a special affection for the usual styles but at the same time we have embraced the new trends focused on hops, we have detected that on the shelves of non-specialized stores, where in principle the customer is more transversal, hopped beers win by a landslide. And despite everything, what I want now is a good Stout ...