“Let’s stop believing that our differences make us superior or inferior to one another.” – Miguel Angel Ruiz Before returning to Canada and re-entering the work force at the age of forty-two, I worked for a few years...

“Let’s stop believing that our differences

make us superior or inferior to one another.”

– Miguel Angel Ruiz

Before returning to Canada and re-entering the work force at the age of forty-two, I worked for a few years in England as a part-time child protection social worker. As things turned out, my working life was completely extinguished a brief eleven years later. My once promising career, began to limp along like an old jalopy, then sputtered, and died.

“Get an education”, my father had said, “and you will always find employment and be able to provide for yourself. No one can take that away from you.” In my case he should have added a caveat: “Unless you develop bipolar disorder.”

I had been living with bipolar disorder for seven years in England and was suffering from a brutish depression at the time of my departure. I chose to leave a failing marriage once it became apparent that my sanity would be compromised if I stayed in it one second longer. How I mustered the energy and courage to leave England I don’t know, but I did, leaving behind everything I owned and had collected in an entire life. I brought with me my two children under ten, two suitcases of clothes and forty Canadian dollars that I found in a box of papers. It was a ridiculously small amount of money to be travelling across eight time zones with young children, but I felt I had no choice. My family paid for our airfares and provided lodging.

I arrived without a job or prospects of any kind, a place of my own to call home, or any possessions, much less a car. I thought to myself, I’ve really gone and done it now. I can’t even go back to England if I wanted to since I trampled the welcome mat on the way out.

I ended up obtaining employment after the first job I applied for primarily because of my experience as a social worker. But what really landed me the job were my dire circumstances. After conducting the interview, the two supervisors in charge of hiring asked me to tell them a bit about myself. I didn’t know what to say so I told them about my travels and the forty dollars which I had spent on the taxi ride from the airport to my sister’s house.

There were two job openings that day. I later learned that both supervisors fought over me after I left. They both wanted the “gutsy woman” on their team who had travelled almost halfway around the world with two young children and not much else.

My misfortune had worked in my favour that day, but it didn’t take long for my luck to run out. I soon discovered I had great difficulty handling the stressors of working full time in child protection—a difficult job for anyone—and the challenges of my newfound responsibilities as a single mother. I should never have taken a job with such a high burnout rate. After only one year of employment, mania had taken me hostage, necessitating a two-and-a-half-month hospitalization and a further three-month convalescence.

A lower-level job with less responsibility and less stress in the children’s disability team was posted while I was preparing to return to work. I readily took this easier job as it would allow me to continue working full time in my profession while allocating more time for child-rearing; there never seemed to be enough energy left over for the children after the exhausting days at work.

My coworkers learned that I had bipolar disorder in my absence. This news proved impossible to keep secret in our small office where everyone knew each other’s business. Learning that my confidential information had been leaked should have been the first clue that I might not be treated respectfully upon my return. I reported for work with a letter from my psychiatrist stating that I was stable and fit for work, but the manager at my workplace wanted a second opinion, which she was entitled to request. I suspect she was concerned about further long absences and my capacity to do the job now that I had developed bipolar disorder (in actuality, I’d already had it for seven years on my first day on the job). The second opinion was to be provided by a consultant psychiatrist affiliated with the organization. After an hour-long interview, he concluded that I was stable and fit for work—and the manager became fit to be tied. She never spoke to me again for the remaining three years I worked in her office or acknowledged me when I passed her in the hallway.

I had become a pariah overnight.

Upon hearing that I had weekly appointments with my psychiatrist, the manager decided I had to ask my immediate supervisor for permission every Friday afternoon to attend these sessions. She had the authority to impose this ruling, but it had never been enforced in our office. Any type of comings and goings, for medical appointments or client visits, were done using an honour system.

A colleague who had MS with more time off work than me did not share my experience. She was never required to ask permission to attend her numerous medical appointments and a second opinion was never requested upon her return to work, even after months of sick leave, because her doctor’s clean bill of health was always accepted at face value. It seemed like unfair bias and a selective application of rules reserved only for me.

There were more affronts from the manager and colleagues alike in the coming months. It was possible that the manager was unaware of her prejudices or the irony that we both worked for a social service organization that championed those with disabilities.

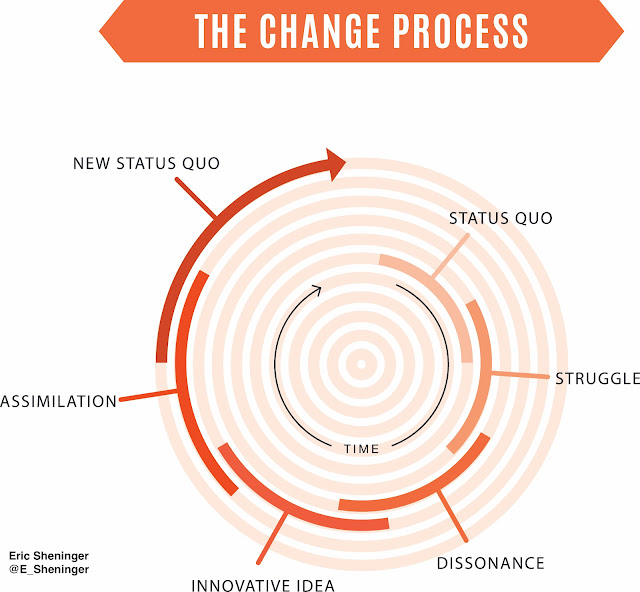

I think the manager’s actions may have been governed by fear. Fear is usually the first emotion we experience when we come face to face with uncharted territory. When these events occurred twenty-five years ago, stigma regarding bipolar disorder was in great abundance; allowing aversion and misinformation to flourish.

The challenge facing workers with bipolar disorder is to maintain a balance between being a productive employee and taking care of our mental health. If I were to offer advice to those currently in the workforce and newly diagnosed, it would be this: Make an honest appraisal of your demeanor before going to work during a hypomanic/manic episode. You may think your behaviour hasn’t changed, but it most likely has, and your colleagues will notice. Another reason to be cautious about going to work when we have hypomania/mania is that we are more likely to make poor decisions, due to the inherent impulsivity of these elevated mood states, possibly putting our jobs in jeopardy.

Bipolar disorder is still a highly stigmatized condition therefore disclosure in the workplace should never be taken lightly. I think there should be a very good reason for doing so—like asking for work accommodations—especially after my experience when the whole office learned I had bipolar disorder without my consent. Beyond a doubt, management started to treat me differently afterwards. Disclosure should be conducted on a case-by-case basis. Make a list of all the pros and cons of disclosing, and share it with someone you trust, before divulging this information to your employer.

When I asked my immediate supervisor for a reference—after receiving a satisfactory performance review and a recommendation for a small raise—she was happy to oblige but only if she could tell prospective employers that I had bipolar disorder. She felt potential employers had the right to know that my attendance had been extremely problematic affecting the whole team. In addition to my nearly six-month leave for mania there had also been two six-week absences for depression and several lesser ones of two-week duration (over a four-year period). In effect she had declined my request. And even though her lack of a referral would make it more difficult for me to find a job, I oddly appreciated her position. I had missed an inordinate amount of work.

I worked seven more years at two different agencies, however my decline in my ability to work was swift after that. The first self-demotion from child protection was one of the best decisions I ever made, but when it became necessary to demote myself a second time, I lost all hope about my future as a worker. By then I was the oldest one in my office, the most experienced and the only one with a master’s degree, yet I had a basic just-left-university-job. Everybody was climbing up in their career, while I was sliding down like a real-life game of Snakes and Ladders.

My difficulties began in earnest after the computerization of my job. I seemed incapable of learning new skills. It reduced my productivity, and I started having to take work home to keep pace, two hours every Saturday and Sunday; all this effort to only just meet the requirements of the job. My lifelong belief that hard work guaranteed success turned out to be fairy-tale.

Unfortunately, it is difficult for some of us with bipolar disorder to maintain continuous employment. Research has shown that only seventy-five per cent of us work—I am a grim statistic—and some of these workers may be underemployed like I was. It would be helpful if employers provided more support than what I received and granted work accommodations like flexible hours or work from home options.

And finally, it’s up to us to assess our stress levels after our diagnoses and our capacity to manage would-be workloads—it can change—so we can choose employment that is commensurate with our capabilities. My skillset decreased over time. With the benefit of hindsight, I wish I had taken an inventory of my abilities before choosing a taxing job as a frontline worker in child protection which included the arduous task of apprehending children. It would have spared me a great deal of grief and may have extended my working life.

Louise Dwerryhouse

Louise Dwerryhouse, a retired social worker, who worked in Canada and the UK, is an advocate, and mental health blogger on “lived experience” living in Vancouver, British Columbia. She was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder late in life, over 30 years ago at the age of thirty-five, and has been living well with the disorder for 10+ years. She writes to those alone, frightened and traumatized by volatile mood swings such as she had in her early days post-diagnosis. Louise tries to lead by example, by sharing her journey to recovery, showing it is possible to live well with the disorder. Her dream is to see a society centred on acceptance, inclusion and less stigma in her lifetime.

Learn more about Louise and read her blogs on her profile page Louise’s talkBD episode on My Bipolar Disorder StoryThe post The Silent Struggle of Bipolar Employment appeared first on CREST.BD.