Every year I celebrate March 2 as “Chickadee Day," the anniversary of my seeing my first chickadee in 1975. This year, several people expressed surprise that I still remember the exact date I saw that first chickadee, but that’s...

Every year I celebrate March 2 as “Chickadee Day," the anniversary of my seeing my first chickadee in 1975. This year, several people expressed surprise that I still remember the exact date I saw that first chickadee, but that’s the day I started my life list, and I'd honestly never noticed a single chickadee in the 23 years before then.

Most birders, including those who are most diligent about keeping lists of the birds they’ve seen, saw chickadees and other common birds long before they started keeping a bird list. Before the eBird app, a lot of people checked off the birds they’d seen on some form of checklist card or in a favorite field guide, not bothering to enter dates for the everyday species they'd already seen before they became serious about listing.

When I started, I’d never identified any wild birds except pigeons, House Sparrows, robins, cardinals, a single Blue Jay I’d seen when I was seven, and a pair of Sandhill Cranes who flew over our class on a field trip at Rose Lake Wildlife Management Area near the Michigan State Campus sometime around 1973. I’d never have had a clue what those extraordinary birds were except that our professor called them out. They were stunningly beautiful and memorable, but I never thought to write the date down.

Something about birds seemed so wonderful and amazing that when my mother-in-law gave me a field guide and binoculars for Christmas when I was 23, I decided that unlike my usual haphazard way of doing things, I was going to be extremely diligent with bird watching. Before I ever took my new binoculars outside, I read that Peterson guide cover to cover, then read both the Golden Guide and Joseph Hickey’s A Guide to Bird Watching. Two and a half months later, the day I set out to be a bird watcher, the only species I saw was the chickadee, which remained alone on my life list for three days, when I saw Mallards on the Red Cedar River. Four days after that, I saw both starlings and House Sparrows. I’d seen cardinals throughout my childhood but didn’t count one on my life list until that March 17. I saw my first pigeons on the 19th, robins on the 20th, and Blue Jays on the 23rd. The only remaining bird I’d already seen but did not have on my life list was the Sandhill Crane. It took over two years, until April 30, 1977, for me to add that species, at Stevens Point in Wisconsin, after we’d left Michigan. It would be well over a decade before I finally saw cranes again in Michigan.

My daughter started a life list in 1988 when she was four, but she kept it up only until she reached 50 species—the benchmark at which I’d promised her I’d give her a brand new copy of the National Geographic Society Field Guide to Birds of North America. My older son Joe was never the least bit interested in keeping a life list, and Tom wasn’t until, when he was six, I dragged Russ and the kids to Grand Marais to see an extremely rare Fork-tailed Flycatcher on May 6, 1992.

|

| I photographed this Fork-tailed Flycatcher in Mexico in 2006, but it looks like the one we saw in Grand Marais in 1992. |

When we got to where the flycatcher had most recently been seen, two Canadian birders were already searching. When we found it, their triumphant exuberance, along with the fact that the bird really was spectacular, inspired Tom to start a life list, too. But unlike his mother, Tom didn’t start with this amazing rarity as his Number One bird and go from there. I’d dragged him to a local wetland that very morning after we saw some birds at the feeder, so he started his life list with those, putting the flycatcher at around #25. It had taken me over 2 months to get my own life list that long.

But that’s the point. There is no right, or wrong, way to keep a life list. Now most birders, including me, put their sightings into Cornell’s eBird app and let the software keep track, providing invaluable data for ornithologists and other scientists as well as personal pleasure for the individual birder. But even using eBird isn’t a requirement to be a bird watcher. As long as you enjoy watching birds, as my birding friend Erik Bruhnke says, it’s all good.

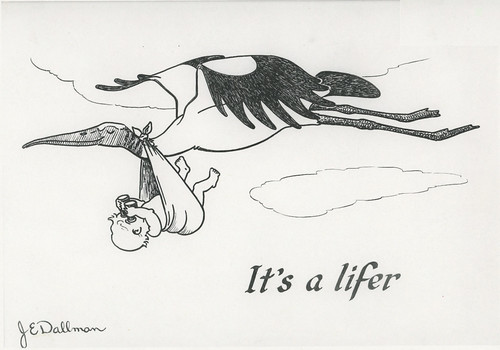

|

| Will Walter keep a life list? Only time will tell. |