We share the planet with more than ten thousand species of birds. An attempt to see representatives of every species would be a fool’s errand. Some birds live in spots Continue Reading ?

We share the planet with more than ten thousand species of birds. An attempt to see representatives of every species would be a fool’s errand. Some birds live in spots so remote, and in such low numbers, that they haven’t been seen in many years. New species are discovered quite regularly, making “all” a vanishing target. Many enthusiasts turn to the pages of field guides and handbooks, allowing the descriptions and illustrations to fuel their imagination of birds that they are unlikely ever to see.

I did just that this week. I dived into my extensive ornithological library is search of birds that I had not stumbled across before. I skipped over some rather uninspiring birds, including the Brown Tanager and the Drab Seedeater, searching for beautiful creatures with exotic names. Here is what I found.

Painting of a Merida Flowerpecker by Joseph Smit – Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (vol. 1870, plate XLVI)

The Merida Flowerpecker was discovered in 1871. It can be found in the scrubby highlands of the Mérida region of Venezuela. A teeny songbird, it is sometimes displaced from good foraging spots by hummingbirds. Like hummingbirds, this flowerpecker feeds mainly on nectar and small insects. Both males and females are mostly black or blueish-grey on top, with reddish-brown undersides. The genus name, Diglossa implies that the bird has two tongues or has two voices, while the species name, gloriosa, is the Latin form of the word glorious. Even though we know almost nothing about the breeding biology of this species, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature considers the Merida Flowerpecker to be of least concern.

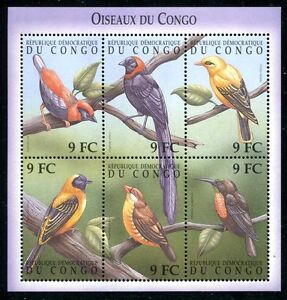

The scholarly community has known about the Red-collared Widowbird since the late 18th century. This bird has a wide, but patchy distribution across the southern half of Africa, and it is known to occupy a wide range of habitats. Roughly twice the size of a flowerpecker, female Red-collared Widowbirds are nondescript in their colouration. Males could scarcely be more impressive. Some are all black, but most have a bright red slash across their throat. Most impressive is the male’s black tail, which is longer than the rest of the bird in some subspecies. Males with the longest tails attract two or three mates, while more poorly-ornamented males remain unmated. Males and females both contribute to nest building, but incubation and feeding of nestlings are carried out by the females alone. The genus name, Euplectes, refers to their woven nest. The species name, ardens, is Latin for glowing or burning, likely a reference to the males’ bright red collar.

The Snow Mountain Mannikin was unknown to the bird world until 1939, when it was found at an elevation of more than four thousand metres in the Snow Mountains of west-central New Guinea. It is a perfectly respectable little songbird with a black face, light brown bib, darker brown back, striped sides, and a robust grey bill suitable for cracking small seeds. The genus name, Lonchura, refers to the pointed tail feathers of some members of the group. What really stands out about this bird is how little we know about it. The IUCN lists the Snow Mountain Mannikin as having a stable population, but that is something of a guess. We do not know if it resides on its breeding range year-round, or if it wanders widely. The nest is built of grass, but nothing else is known of its breeding biology.

And that is one of the most wonderful things about bird biology. Although we know a great deal about birds, much awaits our investigations.

Photo credits: Painting of a Merida Flowerpecker by Joseph Smit – Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (vol. 1870, plate XLVI) – https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%A9ridahakenschnabel#/media/File:DiglossaGloriosaSmit.jpg; Birds of Congo stamp collection, including a male Red-collared Widowbird – www.ebay.com; Snow Mountain Mannikin – www.pinterest.com