Currently I’m spending the three months of the Rains Retreat at Sunyata Buddhist Centre in Ireland. Sunyata runs retreats, but its committee has also been interested in it becoming a monastery for the last few years …. Several of...

Currently I’m spending the three months of the Rains Retreat at Sunyata Buddhist Centre in Ireland. Sunyata runs retreats, but its committee has also been interested in it becoming a monastery for the last few years …. Several of our teachers, including myself, have taught retreats here and on occasion stop by for visits, and they seem so glad to have a monk in residence … so I had an idea …. I had been planning on spending the Rains in solitude in a cabin in Italian Alps under the supervision of Santacittarama Monastery; however, owing to the post-Brexit business of getting a visa and of thereby not being able to enter the European mainland for a subsequent 120 days, that plan fell through. Anyway, Ireland (so far) still remains relatively open for British people, Sunyata is very welcoming, and I still relished the opportunity to spend time in solitude. It seems good to periodically step out of the community routines in order to explore and review my aims and practices.

I arrived on July 13. For the first week or so I felt lacklustre in terms of energy; I didn’t expect it to be much different. Everyone’s life adapts to the social environment they’re in, and when we shift from that, energy shift with it. As the frame of one’s life shifts, there is disorientation. But that’s what I’m here for – to adjust the frame and review the picture.

My life at Cittaviveka is pretty stress-free in many respects. The community is harmonious, nothing much has asked me except to occasionally give a talk. I have however for many years overseen the grounds: tree-planting, general maintenance of the green life of this precious sanctuary. This has always been one of the main attractions of Cittaviveka; a space that’s shared with other life forms. It gets you to adjust to the rhythms of nature. You witness with a sense of awe and delight the comings and goings of the remnants of wildlife that still remain in southern England. There are, from time to time anyway, probably more deer at Cittaviveka than monks. So, yes, over the last thirty years or so, I’ve planned and overseen the conversion of land that was being used for cattle grazing into copses, wild flower meadows and thickets. When one has access to a situation and the resources, it’s just something that one has to do. It used to be pure joy, but nowadays the sense of that weighs on me: there is increasing urgency to support the survival of planetary life, life that is disappearing by the day. And with climate change, how many of these trees will survive the next 50 years?

I was offered a kuti with no duties and I requested one meal a day; the understanding being that we just take it from there and see how it goes. So far, it’s been going very well. I spend my morning in my kuti, and at around 10:30, turn up in the kitchen with my bowl. Food is offered and I give a blessing chant. Sometimes we have a three or four minute conversation in which the most common phrase that I hear is: ‘Do you need anything? Can I offer you anything?’ And my honest and simple reply is: ‘I’m fine thank you, everything is going well.’

That big picture of this is grim. In the last decade also, I have been shaping my responses to the ongoing environmental crisis. I wrote a book on the topic.* I’ve been part of the restoration of the monastery’s native woodland of over 160 acres (65 hectares). I’ve installed solar panels to power the monastery. As a sangha, we decided to use our own coppiced firewood from the forest to heat the buildings. Personally, I abstain from eating fish or meat; that’s about as refined and eco-friendly as I can get as an alms-mendicant. More recently I determined to not drink plastic bottled water if I could obtain water from any other means for 24 hours; so far over the last four years I’ve been able to do this. I minimise water usage by showering only once every five or six days; I collect rainwater to flush the toilet; I gave up on using shaving foam as the canisters containing this froth inevitably go into a landfill. Instead I carry I carry a refillable bottle of oil and mix that with hand soap to shave: a small bottle lasts a year, and doesn’t get thrown away. But there’s not much I can do more I can do; flying in order to teach presents a dilemma that I negotiate on a case-by-case basis. If I don’t fly to a retreat, does that mean that 20-30 people fly to where I am? At least I don’t go on vacation.

And yet, in terms of that big picture, I doubt whether what I do makes any difference. A recent (humorous) comment was that if you really want to avert global warming, better than go vegan or refrain from driving, is to eat a billionaire! Private jets, fleets of large cars, luxury yachts, big mansions: currently the richest 1% of the population are responsible for more twice as much carbon as the poorest 50% (according to Oxfam). Then there’s military expenditure: fighter jets aren’t that carbon-efficient. Statistics certainly contribute to despond. However my practice is simply to do what I can – because that makes a difference to me. It helps to stay focused, sustain the spirit and not go into despair.

So I step back. This is also an opportunity to adjust the frame of my sangha. Locally, at Cittaviveka I am the most senior monk in a situation in which hierarchy can mean a lot. Also, having been here over 35 years, the fact is that I know more about this place than anyone else. Naturally there are projections. So I find myself trying to not be what I think other people might be intimidated by, whilst not being too aloof, available to advise, without appearing as an intrusive know-it-all. In fact I resolve not to express an opinion unless asked to do so. It’s part of community practice. But it’s good to step out of that for a while.

And, with Sangha, as with Dhamma practice in general, there is a bigger picture, one of integrity, generosity and service, one that can telescope down to local details and individuals. Every day, we breathe the shared gift of air, along with our aspiration, grief and joy; and we attend the passage of life and death. Most recently George Sharp passed away. He was the Chair of the English Sangha Trust and was the person responsible for inviting Ajahn Sumedho to Britain to establish a monastery. That monastery became Cittaviveka, which he on his own initiative purchased on a handshake – after being told by the owner that the place was derelict. George was a man of intuition and imagination; and he took risks. As he acknowledged, in his own life this wasn’t always such a successful mix. But Cittaviveka – that was his greatest success, and a source of gladness for himself and for the welfare of many.

I sense that, after bouts of depression in his earlier days, his heart must have been supported by this. He meditated, recollected and maintained contact with Sangha long after his retirement – until his dying day at the age of 89. Having being informed that he had a fatal aneurysm, and accepted that death was on its way, he woke his son one night to say ‘I think it’s happening.’ His son wanted to call an ambulance, but George, feeling it was too late, held his son’s hand, and consoled him saying, ‘It’s alright, it’s alright…’ as he passed peacefully away.

Good Buddhists know how to die well. The last couple of years, supporters whom I’ve seen as inspiring monuments have passed away: Mudita, owner of a Thai restaurant, who had a road-to-Damascus transformation on meeting Luang Por Chah. That was the end of night-clubs and drinking, and the beginning of 40 years of regular practice and providing requisites to monasteries. (She also established The Mudita Trust, which was set up to support poor Thai families so that their daughters didn’t go into prostitution.) Diagnosed with cancer at the age of 84, she declined chemotherapy, with the comment ‘I’ve lived long enough.’ After her death, Tan Nam passed away. He was formerly secretary to the Sangharaja of Cambodia, who left that country with his young family and suitcases just before the Khmer Rouge holocaust. Finding asylum in Britain he held his family together, opened a grocery store, organised events to unify and heal the various factions of the Khmer immigrant diaspora, and presided over the big alms-giving occasions in the monastery. Another great friend, Noy Thompson, recently passed away cheerfully and serenely age of 91, having supported monasteries, worked on and attended retreats, and providing funds to set up The Dharma School in Brighton (now sadly defunct). In this same year, Mae Cham Peng, the Laotian matriarch and a treasure of joy, passed away …. It goes on.

Being a monk, I’m with death and dying a lot. Sometimes it’s like monks are a lymphatic system that drains the grief and the stress that manifests around us and within us. But also we are blood vessels, blessed by connecting to and circulating the finest aspects of human behaviour. Can I be clear enough to be that, and not get clogged? Well, to manage and find balance within all this, I practise embodiment. It’s a matter of feeling emotion without explaining it or nullifying it or philosophising about it; to feel the feeling in the body. This means reframing what one considers ‘body’ to be; in spiritual terms it means ‘that connected field that one experiences oneself as arising within and being affected by’ – such as a body of knowledge, a body of people. Most intimately it’s that pulsing and responsive flow of energies that we associate with a physical form. Mindfulness of that means widening awareness to include that flow as it meets the space around and the ground beneath. Then you can let breathing through that body do the work of bringing an aware life into balance. It keeps the person in perspective.

I do things other than formal meditation practice while I’m here. Qi gong provides ongoing support; it opens the body so that the breath-energy can flow through and replenish. It helps to shift from mental abstract intelligence to directly felt here and now embodied intelligence. Chanting works in a similar way: you have to use your breathing body carefully to get the sound ‘right’. That reminds me that samm? (‘right’) of the Eightfold Path is very close to sama ‘in tune’. In fact the Chinese translated samm? as zheng – ‘aligned’, ‘fitting’ – which gets closer to how the path of practice works – and feels. Is an action or approach in alignment? Does it lead to or support balance? Then can that sense of harmony within one’s personal ‘body’ extend to harmony, balance within the greater ‘body’ of self and others? This requires a considerable skill and growth in terms of heart.

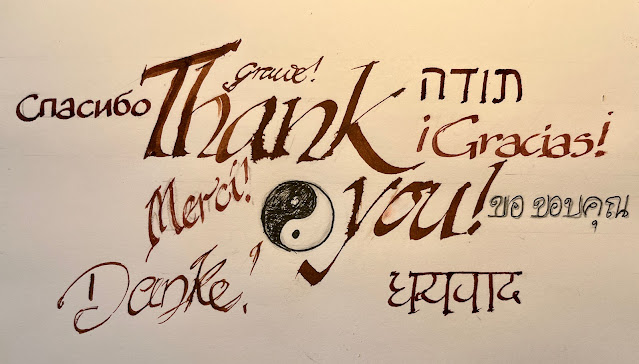

Working on the micro-level of balance, I decided to practise calligraphy. Externally, it’s a way of presenting wise sayings succinctly in a way that does justice to their meaning. It’s perfected by balancing script with empty white space. (For Dhamma sayings, one needs a lot of empty space.) It’s also lightweight and portable – a few nibs, a couple of bottles of ink, paper. Years ago, George Sharp, who was a professional illustrator, noticed some of my sketches and cartoons and gave me a calligraphy pen; and for my own amusement as well as to produce a presentation of the First Sermon that would encourage people to chant it, I ended up producing a series of illuminated manuscripts. Much of that was done amid the grime and fungus-riddled air of Cittaviveka in the early days. For the past 38 years, I’ve done very little in that field. Yet at this time in my life I’d like to do a few things to reset the balance from duty to beauty. So I pick up the pen again.

I had particular sayings and texts in mind, and thought I would write three or four of them during the Rains. After reintroducing myself to pen and ink, and realising how out of touch I was, I narrowed that aim down to maybe doing one. After a few days of more practice I thought I could just get one sentence. A few hour-long sessions indicated that – forget the words, I needed to just get the letters right. That went down to practising to get one stroke where the ink, nib, hand, and mind were flowing together seamlessly. Where the mind wasn’t aiming for the next letter. Where the hand wasn’t dragging the nib. And how that depended on posture and relaxed embodiment. To keep the hand light while sustaining a focus that can maintain awareness of the lines with the space between and within each letter. It’s the kind of all-encompassing balance that characterises Dhamma practice. The Buddha likened it to the ‘right’ way to hold a quail: too tight and you crush it, to loose and it flies away. When it is samm?, awareness engages without expectation, faltering, pushing or hanging back. The deeper significance being that as these programs and more constitute my ‘self’, such ‘fitting’ action dissolves the actor. The frame gets wide and open. The picture is: 'Work in progress ….'

***

*Buddha-Nature, Human Nature (Amaravati Publications). Available through the monasteries or for download at Buddha-Nature