Much like Gene Smith, Jann preferred to work on the ground, preserving the texts and making direct contributions to the field of Buddhism that will be felt for generations. The post The Journey of a Scholar and a Preservationist:...

On July 15th, 2018, Dr. Jann Ronis became the Executive Director of the Buddhist Digital Resource Center. He left a fulfilling job teaching in the Bay Area, and moved cross country to Boston. His first day of work auspiciously turned out to be the holiday of Chokhor Duchen, the Buddha's first Turning of the Wheel of Dharma. His predecessor Jeff Wallman welcomed and helped him settle into what became a period of expansion and growth for the Buddhist Digital Resource Center.

Jann Ronis left his native sunny California to spend extensive time in Asia, studying Tibetan language and the classics of Tibetan Buddhism, including four years in the PRC during the 2000s when it was relatively easy for foreigners to carry out fieldwork in Tibet.

During this decade, he also spent a year working under Gene Smith as a research assistant at the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center. Jann was lucky to come of age in Tibetan Studies as part of the "Gene Generation," a brief golden age during the 2000s when Gene Smith was accessible to all in person and by email, and scholars had immediate access to rare Tibetan texts through Gene's Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center. Finishing his dissertation, an extensive study of Katok based on on-site archival research, Jann became an expert scholar of Tibetan and Buddhist Studies. But Jann didn't want to remain an ivory tower scholar. Much like Gene himself, Jann preferred to work on the ground, preserving the texts and making direct contributions to the field of Buddhism that will be felt for generations.

Scanning precious Buddhist texts that would otherwise be lost and sharing them with teachers, translators, students, and scholars is tilling the field of merit indeed. Jann's auspicious start on Chokhor Duchen, which was entirely accidental, set the stage. We are delighted to mark Jann's five year anniversary and look forward to many more.

Jann Ronis with Tulku Tenzin Gyatso in Kham, 2013.

1

Jann Ronis almost missed seeing the sand mandala at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. The mandala exhibit was supposed to be over, with the mandala created and then ceremonially dissolved. But while the monks were putting finishing touches on the intricate likeness of a divine palace, a disturbed woman jumped onto the mandala and ruined it. So the monks had to begin their delicate, laborious task all over again. Which meant that when Jann Ronis's mother took him to San Francisco for a short visit, he was able to see the monks rebuilding their sand mandala. It was 1991 and the International Year of Tibet was in full swing.

For 17-year old Jann Ronis, the exhibition was a revelation. It wasn't just art and statues and inanimate objects, but six monks carefully making a glorious sand mandala. It was Jann's first encounter with Buddhist monks and the Dharma and Tibet, and Jann was hooked. He said, "This was incredible, this was really something for me to sink my teeth into and learn more about." That was the pivotal moment that changed Jann's life, and set him on the path to all that came thereafter.

When he got back home in San Diego, he went straight to the high school library and checked out books on Buddhism. Prince Siddhartha's journey of renunciation, as rendered by Herman Hesse, touched him deeply. He found the Zen Center of San Diego, which was just six miles from his house, and started attending their Zen meditation sessions with Roshi Charlotte Joko Beck, one of the first prominent women Zen teachers in the US. All through his senior year of high school, he continued with Zen meditation, but intellectually he hankered for something more. It was that summer, on their family vacation to Maui in Hawaii, that Jann found what he was looking for, in the phone book.

The first night of the trip, Jann took out the phone book and started searching, flipping through some Japanese temples and some Chinese temples, and there it was. Karma Rimay Osel Ling, a Tibetan Buddhist temple at the foot of the Haleakala Volcano. He called them. They were a Buddhsit temple. They had a Tibetan lama, and they did puja every morning at 6:30am. The temple invited Jann to join the puja. Early the next morning, Jann's father dropped him off. Jann's parents were secular atheists and raised their children without religion. Although not thrilled with their son's embrace of Buddhism, they supported him.

Jann didn't know what a "puja" actually was, only that he wanted to be a part of it. He met the teacher, Lama Sonam Tenzin (who had been trained at Tashilhunpo Monastery). At the beginning of the puja, Jann fumbled his way through some prostrations and then the lama sat Jann next to himself. Jann chanted, in handwritten phonetics, a long and thoroughly unfamiliar hymnal that included the Heart Sutra, The Thirty-Five Confession Buddhas, the Vajrasattva mantra, and prayers to various lamas of the past and present. As he said, "I could have run out screaming or I was there for the rest of my life."

He spent the rest of the morning with the Lama at the temple although there was a giant language barrier: the Lama spoke no English and Jann spoke no Tibetan. He came back the next day, and the day after that. The next time he went to the temple, Jann took refuge and became a Buddhist. Lama Sonam Tenzin gave Jann the Dharma name Tsöndru Gyatso, Ocean of Perseverance.

Karma Rimay Osal Ling, a Karma Kagyu Dharma Center in Hawaii, where a 17-year old Jann Ronis took refuge. Coincidentally, Jann and the temple were born the same year, 1974.

2

In the fall of 1995, Jann did a semester's study abroad through the Antioch Buddhist Studies program in Bodh Gaya. He lived in the Burmese vihara, circumambulated the Stupa everyday, meditated regularly, ate every meal at the Tibetan tent restaurants, and hung out with the monks. With his short hair, he practically looked like a monk himself. He loved what he was learning, and it was right at the source, where the Buddha sat under a Bodhi tree and gained enlightenment. It felt like a blessed time and place. One of the faculty, the scholar Christian Wedemeyer who was a graduate student at that time, noticed how much Jann seemed to be in his element, steeped in Buddhist studies in Bodh Gaya, and advised him, "You have two paths: you can become a Dharma bum or you can go to graduate school."

At the end of the semester abroad, Jann went home for his final semester of college at Humboldt State University and started preparing for graduate school. But in order to get into grad school, Jann needed to improve his Tibetan. He enrolled in the University of Wisconsin study abroad program in Nepal—and spent half a year in Kathmandu in a homestay with a Tibetan family at the base of Swayambhu learning colloquial and literary Tibetan. The second half of the year, Jann spent in Dharamsala taking classes at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives with Geshe Sonam Rinchen. He also had one-on-one reading sessions with Sangye Tendhar, reading a text by Patrul Rinpoche that was a dialogue between an old man and a young man. Back in the States, Jann moved to Santa Barbara and sat in on Alan Wallace's classes. Having read some of the masterworks of Tibetan Buddhism with some of the best teachers, Jann Ronis was now ready for graduate training.

A photograph taken by Jake Dalton's mother on a visit to Bodh Gaya, which somehow happened to capture Jann milling in the crowd. Years later, Jake Dalton found the photo in his mother's collection and instantly recognized Jann.

3

At first, graduate school for Jann Ronis was just a means to an end. He didn't want to teach, he just wanted to live in Asia. Going to graduate school was just a parentally approved way to spend time in Asia! The reason he chose the University of Virginia in Charlottesville was not just because it was the largest Tibetan Studies program in the United States but because Jeffrey Hopkins taught there—Hopkins who had authored more books than anyone else. But during his PhD training at UVA, Jann studied under and taught his first classes for David Germano, who then became his main teacher and mentor. David Germano was an incredible lecturer and studying under him, and teaching his undergraduates, Jann fell in love with teaching himself. It was another transformation. "The more I taught, the less I meditated," Jann explained. He was moving away from a Buddhism of the body to a Buddhism of the mind.

Jann with friends in front of the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa.

It was David Germano who insisted that he do his fieldwork in Tibet rather than India. David Germano, who had good contacts all over Tibet, sent him to Katok Monastery in Kham. The first time Jann went to Katok, he went for just a week to meet the Khenpo and the monks and to scope out the place. Even though his Tibetan was very good, his Kham dialect was still in its infancy. When the Khenpo said, "The Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha," his accent was so strong that Jann couldn't even understand what he meant.

In the fine tradition of Tibetan masters testing their students before taking them on, the Khenpo gave Jann two tasks: to learn the Kham dialect and to read the Mipham text Sword of Wisdom. Mastering these two tasks and going back to Katok, Jann was now ready to be taught by the Khenpo of Katok.

By that point, Jann had already spent two years in China, first in Beijing and then Chengdu. In Beijing, he taught English at a university in the morning and studied Tibetan and Chinese at the Nationalities College in the afternoon. That was becoming a recurring theme of Jann's life, being both teacher and student at the same time, sometimes with the same person. In Chengdu, he had studied Chinese at Sichuan Nationalities and hung out in Wuhouci with his Tibetan friends. With both his Buddhist philosophy and his language training up to par, he was ready to embark on a rigorous study with monks at a remote Tibetan monastery in the mountains of Kham.

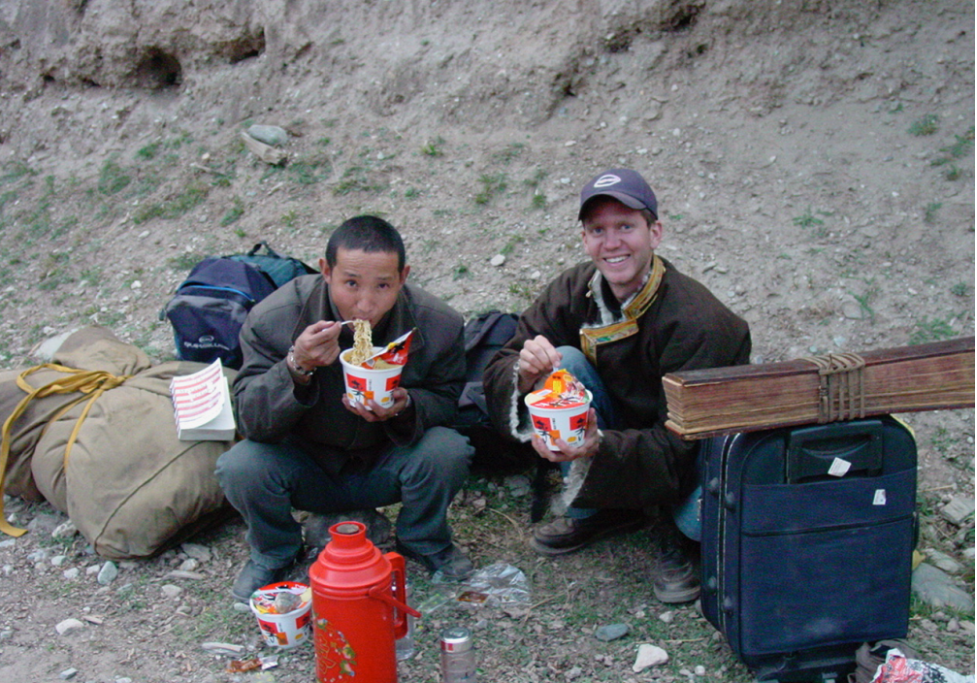

The scholar Karma Delek and Jann are enjoying a quick meal of instant noodles on the road from Palpung to Katok, in 2002. We can see that Jann has placed his Tibetan text carefully on his suitcase rather than on the ground.

This was back in 2002, and Katok was primitive then, with no running water or electricity. When Jann returned, all the student monks were surprised to see him. But not the Khenpo. The Khenpo always knew that Jann would return. In fact, the Khenpo now took on Jann as his personal student. Jann joined regular class with the other monks, and followed that up with extra lessons with the Khenpo every day. In return, Jann taught the Khenpo about America, about which the Khenpo was very curious indeed.

Katok is a major Nyingma monastery founded by Dampa Deshek a thousand years ago in 1159. A remote monastery in Derge, Katok was known for its preservation of the Kama, or Spoken Word, tradition.

Katok was unique in the way it taught their monks, consciously teaching in the way it had taught for centuries. There was no set curriculum, and all the monks at the monastery, no matter their level or year of study, joined the Khenpo daily for classes in the large one-room school house. Then Khenpo taught like Socrates, standing in front of all his students and extemporaneously speaking, explaining, debating and demonstrating. Living and learning with the Katok monks, supplemented with personalized daily lessons from the Khenpo, Jann was getting an exceptional education in Buddhist philosophy and dialectics. Jann's PhD from the University of Virginia was now becoming not only a PhD about Katok, but a PhD from Katok.

Katok Monastery in 2004 during a Tsechu festival. Katok is a major Nyingma monastery founded by Dampa Deshek a thousand years ago in 1159. Photo by Jann Ronis.

4

In another recurring theme of his life, Jann's dissertation about Katok had a lot of support and help from Gene Smith, the legendary Tibetologist and Librarian at the Library of Congress who had founded the largest online library of Tibetan texts in the world. (Gene's Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center has now become the Buddhist Digital Resource Center.)

In 1999, when Jann was a new student at the University of Virginia, at one of his reading seminars, his professor David Germano walked in carrying an envelope from Gene Smith, which Germano passed around like something precious to his students. When the CD came to Jann, he copied the entire contents (about one dozen Tibetan texts) onto his laptop. That was Jann's first transmission from Gene Smith and the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center.

Of course, Jann couldn't read the Ume texts then. He met Gene for the first time in 2003, when Gene came to UVA for a conference on Tibetan History and Historiography. David Germano in his introduction said, "With Matthew Kapstein, Leonard van der Kuijp, and Gene Smith here, we have the three Buddha bodies—the Nirmanakaya, the Sambokaya, and the Dharmakaya—of Tibetan historiography." Jann saw how these scholars, whom the grad students looked up to, in their turn looked up to and revered Gene. Gene gave a talk on the "Organization among the Nomads of northeastern Amdo and Problems of Toponymns and Monastic Organization."

The first time Jann introduced himself and spoke to Gene, Gene asked if Katok Dampa Deshek was really the younger brother of Phagmodrupa Dorje Gyalpo, as the histories claimed. Jann had simply accepted the histories and never questioned them. With one question, Gene upended his Katok narrative. Throughout the rest of Jann's dissertation work and writing, Gene continued to provide similarly clarifying and insightful questions, ideas, and notes. Jann even worked as a research scholar for Gene and TBRC for a year, before going back to UVA to finish up his dissertation. Jann remembers that Gene advised him to finish; Gene told him that he always regretted not finishing his own dissertation.

But by putting off his own dissertation and doing the work of saving the texts instead, Gene made all the other dissertations possible. Jann's own dissertation on Katok depended not only on Katok's own library collection, but also on texts scanned and archived by BDRC.

So it's apt, after all, that Jann Ronis followed in Gene Smith's footsteps to become Executive Director of the library and organization that Gene founded.

5

Jann in Katok with friends in 2002.

After finishing his dissertation, an excellent study of Katok titled "Celibacy, Revelations, and Reincarnated Lamas: Contestation and Synthesis in the Growth of Monasticism at Katok Monastery from the 17th through the 19th Centuries," and graduating from the University of Virginia, he went on to teach at Berkeley for many years. In 2018, Jann left Berkeley to become the Executive Director of the Buddhist Digital Resource Center. It was a decision he had agonized over, because he adored his job teaching Tibetan and Buddhism at Berkeley. It was Burkhard Quessel, the Tibetan librarian at the British Library who told him to quit making a list of pros and cons, and to simply accept; that he had to say yes to this job, because it was an amazing opportunity and that he would be ruining his work karma if he said no. As a junior scholar mentored by Gene, Jann had seen firsthand how critical the organization was for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies. He knew how crucial the library had been for his own research, not to mention all the love and admiration he had for Gene. A chance to continue and shape this organization sounded like a dream come true.

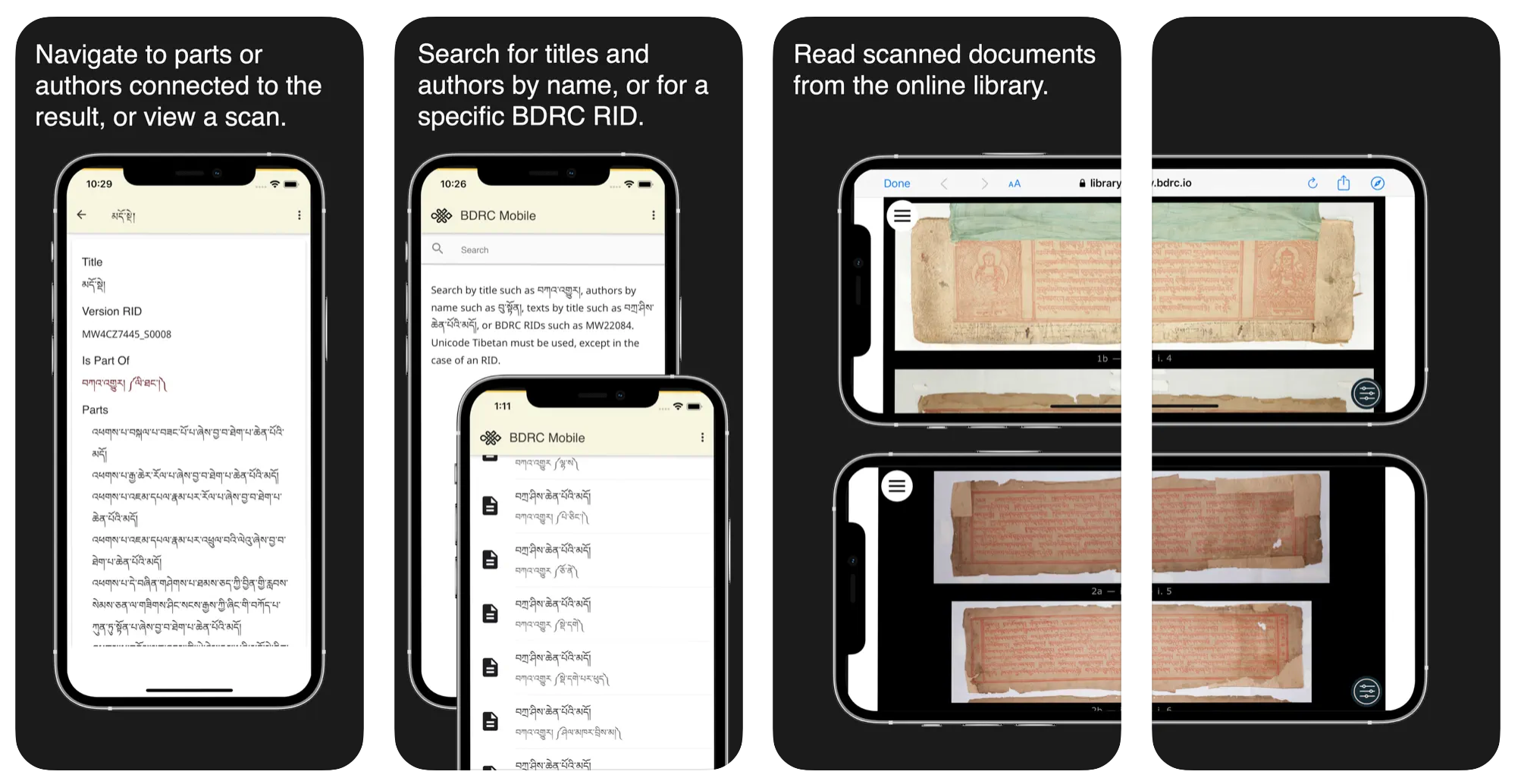

Under Jann's leadership, BDRC launched the Buddhist Digital Archives, a public digital library with a new interface for BDRC's vast archive and an expanded library search platform connecting a whole universe of Buddhist texts and a range of different partners. Gene, who embraced technology to advance Buddhism, would have been delighted to see this latest state of the art technology deployed in service to Buddhist literature. Under Jann's tenure, BDRC launched ambitious text preservation projects in Cambodia and Thailand. BDRC's Mongolia project also began that year, scanning and preserving tens of thousands of Tibetan texts from the National Library of Mongolia and making them available to Mongolians, Tibetans, and the world. Meanwhile, BDRC's work with Tibetan partners remained more important than ever; the organization was scanning thousands of more Tibetan texts and adding them to the archive.

At the Songtsen Library, founded by Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpoche, in India.

If a random woman had not damaged a sand mandala in San Francisco, if the Tibetan center in Maui had not picked up their phone, if Christian Wedemeyer had not advised Jann to go to grad school (or to become a Dharma bum), if Jann had not gone to UVA, if the Katok Khenpo had not accepted him as a student, if Jann and Gene had never met, if Jann hadn't become Gene's research scholar at TBRC—what would that counterfactual even look like? It's a series of fortuitous turning points that led Jann Ronis to the Buddhist Digital Resource Center. But perhaps, with his expertise in Buddhist Studies, his deep love and mastery of Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan language, his experience in Digital Humanities, and his decade-plus training at Virginia and Katok, perhaps Jann was always destined to be the Executive Director at the Buddhist Digital Resource Center. Perhaps, it's karma.

Jann giving a talk on BDRC's digital preservation work at the Library of Congress, March 2023. Photo by LOC's Tien Doan.

The post The Journey of a Scholar and a Preservationist: Jann Ronis Celebrates Five Years as Executive Director of BDRC appeared first on Buddhist Digital Resource Center.