By Manos Antoninis, Director of the GEM Report ‘Everyone’s talking about which AI tool to use, but nobody’s talking about why we’re using them in the first place’, observed a secondary school teacher in the United States. This sums up the current state of AI in education: a whirlwind of excitement and experimentation, often overshadowing […] The post The Trojan Horse in the classroom: navigating AI’s impact on the International Day of Education appeared first on World Education Blog.

By Manos Antoninis, Director of the GEM Report

‘Everyone’s talking about which AI tool to use, but nobody’s talking about why we’re using them in the first place’, observed a secondary school teacher in the United States. This sums up the current state of AI in education: a whirlwind of excitement and experimentation, often overshadowing critical reflection on its actual value and the likely consequences.

AI has a special allure for many education experts who believe in its potential to revolutionize teaching methodologies, personalize learning experiences and streamline administrative tasks. But while the potential benefits of AI in education remain largely unknown, the risks of using classrooms as a testing ground for these technologies are undeniable.

One risk is in the form of the commercialization of education. We are constantly reminded how the global market for AI in education will surge in the coming years, although it is important to remember that exaggerated claims about technology tend to go hand in hand with exaggerated estimates of its future global market size. We would be fooling ourselves if we thought AI companies are more concerned with educational outcomes than their bottom line. Meanwhile, with a few exceptions, consumer protection laws are still fragmented and opaque.

As we are beginning to realize, control of AI has also become a larger issue beyond consumption of goods, touching upon consumption of votes, with fact-checking on popular social media abandoned and users left to their own ‘devices’ in their search for reliable information. This quote by philosopher Hannah Arendt is a reminder:

“A people that can no longer distinguish between truth and lies cannot distinguish between right and wrong. And such a people, deprived of the power to think and judge, is, without knowing and willing it, completely subjected to the rule of lies. With such a people, you can do whatever you want.”

Eight years on from the creation of the term ‘fake news’, there is a question about how we want to ensure that learning spaces are protected from this trend: can critical thinking and open debate be fostered in the face of strong outside influence? Our responsibility, as we reflect on education in this context, is to ensure our focus remains on students and their learning experience.

Certainly, there are pockets of benefits for some learners, particularly for breaking down language barriers, and for assisting learners with a disability. However, a blanket acceptance of AI into education risks backfiring. Our other blog this week, which provided an update about bans on smartphones in school, reminded us that the algorithms in these phones end up making many school environments less safe.

The ability of AI to cut corners for learners in accessing content and formulating arguments also requires thought. This has great benefits on the one hand. But we do not always stand to gain from cutting corners where learning is concerned. As students, we did not write particularly great essays, if we are honest about it, but it was the process of writing them that was important – a part we should be careful to protect.

The ship has pretty much set sail

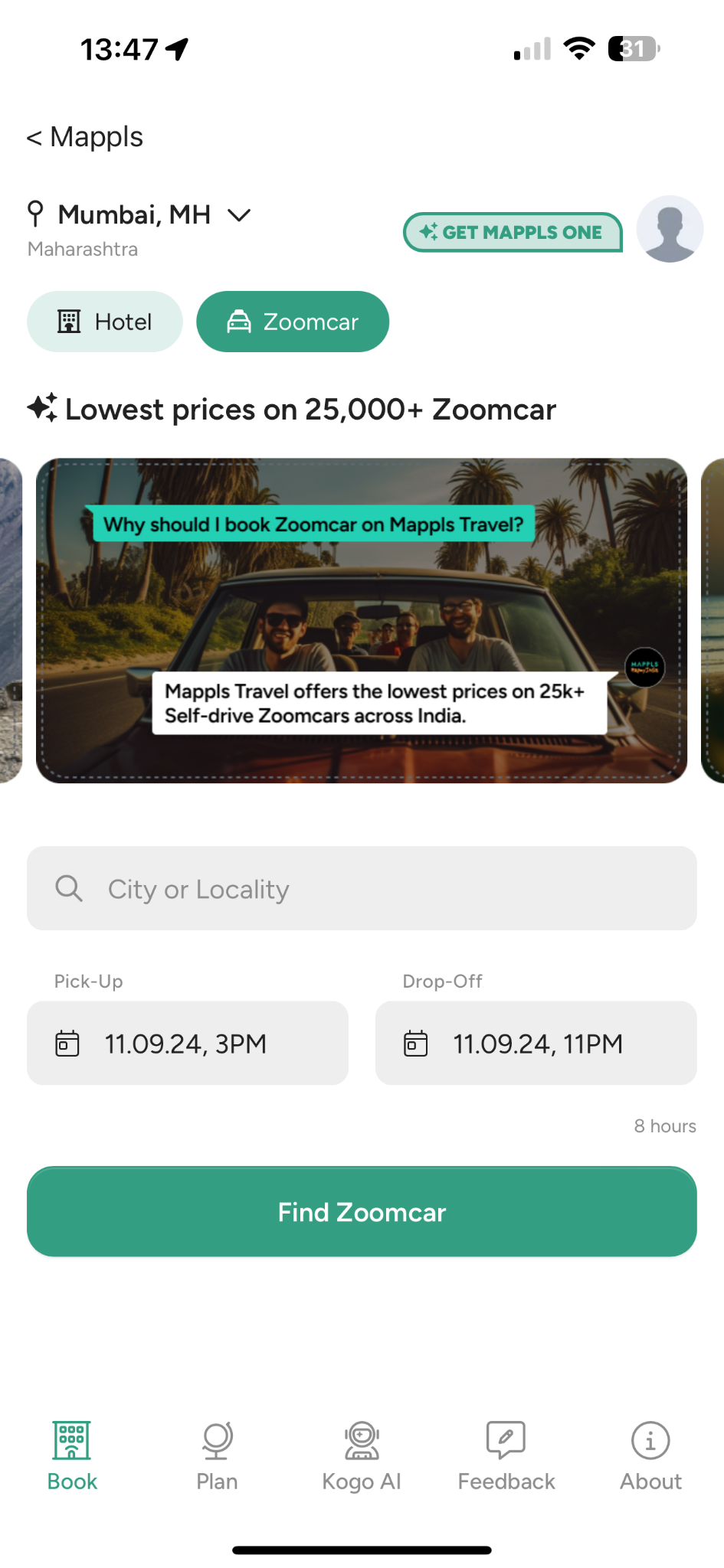

Perhaps it is too late to talk of putting the brakes on. Many countries have been embracing AI for some time. In the United Kingdom, between April and November 2023, the share of primary and secondary school teachers who used generative AI to aid with their schoolwork from 17% to 42%. This month, the government of the United Kingdom announced, as part of its AI strategy, its intention to support universities to develop new AI courses co-designed with the AI industry to ‘train the tens of thousands of AI professionals needed by 2030‘. It has also supported AI tools to help teachers with feedback and marking.

China laid out goals in July 2024 to build a domestic AI industry worth nearly $150 billion and to make the country an AI ‘innovation centre’ by 2030. It has invested heavily in an adaptive tutoring platform, Squirrel AI, which uses large-scale data sets and camera surveillance to improve standardized test performance. In Finland, about half of schools use the ViLLE platform for immediate feedback and analytics on student assignments. In the Punjab province of India, IRIS, an AI-powered teacher, is now offered. The Republic of Korea has decided to take the plunge towards AI textbooks from this March. In the United Arab Emirates, an AI tutor tailors lessons to individual students’ needs, offering real-time analytics. Uruguay has been integrating AI into classrooms since 2017 through Ceibal, its national agency for innovation through technology. Teachers were even swapped with AI tutors in one school programme in Arizona.

At the higher education level, several universities in Latin America are expanding their AI courses. Colombia has 18 graduate-level academic programmes and one undergraduate degree in Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, while Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Peru have also expanded their academic programmes.

Countries are not blind to the risks, however, and many are proactively addressing some of the potential challenges. Ireland, for example, is producing guidance on the use of AI in teaching and learning, and France is addressing the public policy ethical considerations and challenges for of the use of AI in education. The African Union has a continental AI strategy laying out a blueprint for how African nations should approach the governance and oversight of AI. But education technology products are already changing faster than anyone could evaluate them. Is it any surprise many countries are struggling to keep pace?

Why the rush?

However difficult it is to do so, it is important to take the time to reflect on the key questions, which the 2023 GEM Report raised and which apply for all forms of technology, AI included. Is it appropriate, i.e. what evidence do we have that it improves learning and what type of learning? Is it equitable? Is it scalable? And is it sustainable?

Ultimately, what problem are we trying to fix in our education systems? We can no longer turn our eyes away from the fact that adolescents’ reading proficiency levels in middle- and high-income countries have declined dramatically in the last 10 years. This is precisely the period during which digital technology and its consequences have taken young people’s daily lives by storm.

As Virgil’s Aeneid goes ‘Either there are Greeks in hiding, concealed by the wood, or it’s been built as a machine to use against our walls, or spy on our homes, or fall on the city from above, or it hides some other trick: Trojans, don’t trust this horse.’

Without better evidence on whether AI makes educational sense or not, the only approach we can take must be with caution.

In 2024, global debates erupted about regulations of smartphones in school, an initiative that could limit the pervasiveness of AI in classrooms. On this International Day of Education, we encourage countries to make 2025 the year when they take a stand on their broader position to ensure that AI in education remains on our terms.

The post The Trojan Horse in the classroom: navigating AI’s impact on the International Day of Education appeared first on World Education Blog.