I met Winona Hastings on the basketball court in Supai village. It was a couple hours after perhaps half the tribal community had packed into Havasupai Elementary School for its eighth grade promotion ceremony. Indian fry bread had been served. Family photos were taken. Hastings’ two young daughters, Kyla and Kayleigh, chased each other across […] The post Investigating the Bureau of Indian Education — and Trump’s efforts to turn it into a school choice program appeared first on The Hechinger Report.

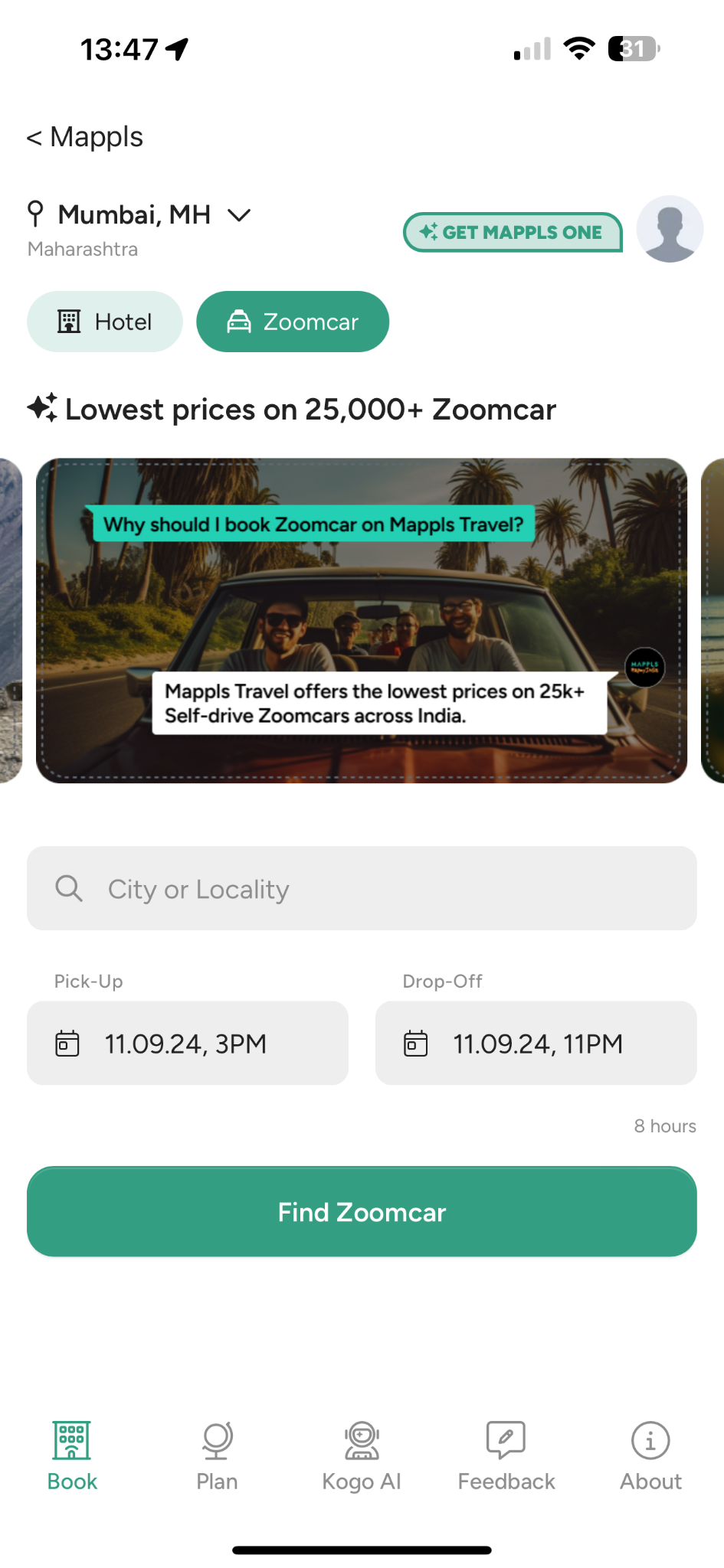

I met Winona Hastings on the basketball court in Supai village.

It was a couple hours after perhaps half the tribal community had packed into Havasupai Elementary School for its eighth grade promotion ceremony. Indian fry bread had been served. Family photos were taken.

Hastings’ two young daughters, Kyla and Kayleigh, chased each other across the basketball court as she watched from a nearby bench. She fanned herself under the desert sun, already scorching on a May afternoon last year, and talked about sending her oldest, Kyla, to kindergarten in the fall. The 33-year-old single mother of two said she wished there were another school to enroll her daughter.

“I want change for my kids,” Hastings said.

Run by the federal government, Havasupai Elementary is the only school in Supai.

It’s also where Hastings — a 2009 graduate — has tearful memories of bullying and chronic teacher turnover and not learning very much. She never finished high school and said she still struggles with basic math as an adult. Her experience at the Supai school echoed that of nine Havasupai students who in 2017 sued the federal government for the poor quality of education offered there and a lack of protections for students with disabilities.

Their lawsuit resulted in two historic settlements, one of which required the formation of a new school board — the first in many years. Hastings, at the invitation of the tribal council, agreed to join the board.

“I got the short end of the stick here. I had no one like me in charge of the school,” Hastings said. Now, she added, “I can be an advocate for our kids.”

Related: A lot goes on in classrooms from kindergarten to high school. Keep up with our free weekly newsletter on K-12 education.

Last year, photojournalist Matt Stensland and I visited Havasupai Indian Reservation — a tiny, remote community on a tributary to the Grand Canyon — for a story about the elementary school and the impact of the students’ lawsuit. Visitors have two ways of getting into Supai: book a private helicopter flight — and bring cash — or hike 8 miles into the canyon. We made our way by foot as part of a bigger project on the Bureau of Indian Education and whether a decade-long reform had led to improvements.

The visit clarified what nearly 100 educators within the BIE, students and graduates, parents, elders, Native education advocates and government officials told me over the past few years. The obstacles, they said, that the BIE faces in doing its job are immense. In Supai, the principal relies on Amazon Prime for basic classroom materials delivered by mule train. Wind delays to the helicopter schedule may cancel classes for the week when a teacher can’t fly in.

Nationally, the underfunded BIE oversees and supports 183 different schools in 64 different tribal communities across nearly two dozen states. Its schools enroll many kids living in difficult situations, often as a result of past federal policies. The bureau also runs a college and university, residential dorms, college scholarships for Native students and more.

Related: How a tribe won a lawsuit against the federal government — and still lost

The bureau has made some serious missteps over the years, including a bungled response to the pandemic and notorious opacity that makes public accountability nearly impossible. The inspector general of the Interior Department, which includes the BIE, recently issued a blistering report on safety and health deficiencies in Supai. Most teachers I met there last May had all but given up hope that the problems above their school would be fixed.

But I also found that the 2014 reform effort has begun to bring some modest progress. The so-called Blueprint for Reform — unveiled just as budget cuts swept most of the federal government — took years to show results. The pandemic also scrambled much of the early stages of that work. But in the last couple years, the agency has rebuilt or renovated many of its most dilapidated campuses. Funding has gone up, as have graduation rates. The BIE launched a new data system to track student performance.

In Supai, the lawsuit, too, has started to have an impact. A new principal will soon finish her first full year. The school got new computers and a library. There’s an actual curriculum in all subjects.

Now President Donald Trump has launched an aggressive downsizing of government that will bring sweeping layoffs to the Interior Department and the BIE, and turn the bureau into a school choice program. It’s unclear how those layoffs will affect individual schools like Havasupai Elementary, and what school choice looks like in a place as isolated as Supai. The federal government, meanwhile, has treaty obligations to Native American tribes dating back hundreds of years; advocates and lawmakers want to understand how the Trump administration’s actions undermine, if at all, the government’s trust responsibility with tribal nations.

I first heard about the Havasupai litigation while covering the BIE’s challenges during Covid, and it took years to get access to Supai. The tribe extended its lockdown and restricted visitors until early 2023. I spoke to mothers, teachers and tribal leaders in the meantime. Before the Havasupai Tribal Council approved our visit, we signed a media release that limited our interactions with residents and what we could capture in photos. The tribe is a sovereign government, with its own laws, and recreational visitors on a very long waitlist all agree to the tribe’s tourism code.

Trailing many of those tourists, we trekked into Supai until, with 3 miles left to go, I rolled and severely injured my ankle. Matt delicately helped me hobble the rest of the trek, but after my right foot swelled to twice its size by morning, some very generous staff at Supai’s health clinic loaned me a pair of crutches. (And thankfully, we’d already planned to take the helicopter back to the trailhead.)

Related: Native Americans turn to charter schools to reclaim their kids’ education

In some ways, the crutches turned out to be a blessing: They helped break the ice with many educators and parents and young people. Locals approached me to ask what I did to myself or if I needed help.

Hastings sat with me on the bench and explained why she’d joined the school board. “The kids need love, need to see that this community loves them,” she said.

She told me how, in a school board meeting, she’d learned that the school’s popular kindergarten teacher planned to remain at Havasupai Elementary for another year. He was a veteran, in his fifth year there, and Hastings was relieved Kyla wouldn’t be learning from a novice or someone there just to make some extra money before retiring completely.

That had been her experience at Havasupai Elementary.

“We got the not-wanted teachers — the retirees, the new hires,” Hastings said. “It makes you feel abandoned, like no one cares.”

Yet last fall, when Kyla took her first steps through the school doors, Hastings discovered that the popular kindergarten teacher had decided to retire after all. She kept her daughter enrolled anyway, hoping she would soon learn her ABCs and what one plus one equals. Two months into the school year, though, Hastings didn’t see any progress in Kyla. A traumatic summer flood and better job prospects convinced her to move the family out of the canyon, to the nearest town with a traditional public school.

She might have stayed, Hastings said, if that teacher hadn’t quit.

“He made me cry when he said he does it because he likes being here, that he likes the kids,” she said. “We need more people like him.”

Trump set an April deadline for the BIE to submit a plan that would offer families a portion of federal funding to spend on school choice. I’ll pay close attention to what’s in that plan, and what it means for students and families.

Please share your questions with me too.

Contact staff writer Neal Morton at 212-678-8247, on Signal at nealmorton.99, or via email at [email protected].

This story about Supai village was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality innovation in education, in collaboration with ICT (formerly Indian Country Today). Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter. Sign up for the ICT newsletter.

The post Investigating the Bureau of Indian Education — and Trump’s efforts to turn it into a school choice program appeared first on The Hechinger Report.